This article needs additional citations for verification. (May 2016) |

The Battle of the Dnieper was a military campaign that took place in 1943 on the Eastern Front of World War II. Being one of the largest operations of the war, it involved almost four million troops at one point and stretched over a 1,400 kilometres (870 mi) front. Over four months, the eastern bank of the Dnieper was recovered from German forces by five of the Red Army's fronts, which conducted several assault river crossings to establish several lodgements on the western bank. Kiev was later liberated in the Battle of Kiev. 2,438 Red Army soldiers were awarded the title Hero of the Soviet Union for their involvement.[12]

| Battle of the Dnieper | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Eastern Front of World War II | |||||||||

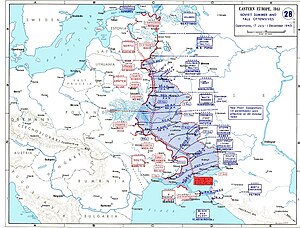

Map of the battle of the Dnieper and linked operations | |||||||||

| |||||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||||

|

|

| ||||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||||

|

|

| ||||||||

| Units involved | |||||||||

|

|

| ||||||||

| Strength | |||||||||

|

26 August: 2,633,000 men (1,450,000 reinforcements)[3] 51,200 guns and mortars[3] 2,400 tanks and assault guns[3] 2,850 combat aircraft[3] |

- 85,564 personnel. | ||||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||||

|

Krivosheev: 1,285,977 men[8]

Frieser: 1,687,164 men[9]

- 290,000 killed or missing - 1,000,000+ in total |

Forczyk:[11] - 102,000 killed or missing - 372,000+ in total Unknown | ||||||||

Strategic situation

editFollowing the Battle of Kursk, the Wehrmacht's Heer and supporting Luftwaffe forces in the southern Soviet Union were on the defensive in southern Ukraine. By mid-August, Adolf Hitler understood that the forthcoming Soviet offensive could not be contained on the open steppe and ordered construction of a series of fortifications along the line of the Dnieper river.

On the Soviet side, Joseph Stalin was determined to launch a major offensive in Ukraine. The main thrust of the offensive was in a southwesterly direction; the northern flank being largely stabilized, the southern flank rested on the Sea of Azov.

Planning

editSoviet planning

editThe operation began on 26 August 1943. Divisions started to move on a 1,400-kilometer front that stretched between Smolensk and the Sea of Azov. Overall, the operation would be executed by 36 Combined Arms, four Tank and five Air Armies. 2,650,000 personnel were brought into the ranks for this massive operation. The operation would use 51,000 guns and mortars, 2,400 tanks and 2,850 planes.

The Dnieper is the third largest river in Europe, behind only the Volga and the Danube. In its lower part, its width can easily reach three kilometres, and being dammed in several places made it even larger. Moreover, its western shore—the one still to be retaken—was much higher and steeper than the eastern, complicating the offensive even further. In addition, the opposite shore was transformed into a vast complex of defenses and fortifications held by the Wehrmacht.

Faced with such a situation, the Soviet commanders had two options. The first would be to give themselves time to regroup their forces, find a weak point or two to exploit (not necessarily in the lower part of the Dnieper), stage a breakthrough and encircle the German defenders far in the rear, rendering the defence line unsupplied and next to useless (very much like the German Panzers bypassed the Maginot line in 1940). This option was supported by Marshal Georgy Zhukov and Deputy Chief of Staff Aleksei Antonov, who considered the substantial losses after the Battle of Kursk. The second option would be to stage a massive assault without waiting, and force the Dnieper on a broad front. This option left no additional time for the German defenders, but would lead to much larger casualties than would a successful deep operation breakthrough. This second option was backed by Stalin due to the concern that the German "scorched earth" policy might devastate this region if the Red Army did not advance fast enough.

Stavka (the Soviet high command) chose the second option. Instead of deep penetration and encirclement, the Soviet intended to make full use of partisan activities to intervene and disrupt Germany's supply route so that the Germans could not effectively send reinforcements or take away Soviet industrial facilities in the region. Stavka also paid high attention to the possible scorched earth activities of German forces with a view to preventing them by a rapid advance.

The assault was staged on a 300-kilometer front almost simultaneously. All available means of transport were to be used to transport the attackers to the opposite shore, including small fishing boats and improvised rafts of barrels and trees (like the one in the photograph). The preparation of the crossing equipment was further complicated by the German scorched earth strategy with the total destruction of all boats and raft building material in the area. The crucial issue would obviously be heavy equipment. Without it, the bridgeheads would not stand for long.

Soviet organisation

edit- Central Front (known as the Belorussian Front after 20 October 1943), commanded by Konstantin Rokossovsky and accounted for 579,600 soldiers (took no part in the Dnieper battle after 3 October)

- 2nd Tank Army, led by Aleksei Rodin / Semyon Bogdanov (since September)

- 9th Tank Corps, led by Hryhoriy Rudchenko (KIA), Boris Bakharov

- 60th Army, led by Ivan Chernyakhovsky

- 13th Army, led by Nikolay Pukhov

- 65th Army, led by Pavel Batov

- 61st Army, led by Pavel Belov

- 48th Army, led by Prokofy Romanenko

- 70th Army, led by Ivan Galanin / Vladimir Sharapov (September – October) / Aleksei Grechkin (since October)

- 16th Air Army, led by Sergei Rudenko

- Voronezh Front (known as the 1st Ukrainian Front after 20 October 1943), commanded by Nikolai Vatutin and accounted for 665,500 soldiers

- 3rd Guards Tank Army, led by Pavel Rybalko

- 1st Tank Army, led by Mikhail Katukov

- 4th Guards Tank Corps, led by Pavel Poluboyarov

- 1st Guard Cavalry Corps, led by Viktor Baranov

- 5th Guards Army, led by Aleksei Zhadov

- 4th Guards Army, led by Grigory Kulik / Aleksei Zygin (KIA) / Ivan Galanin

- 6th Guards Army, led by Ivan Chistyakov

- 38th Army, led by Nikandr Chibisov / Kirill Moskalenko (since October)

- 47th Army, led by Pavel Korzun / Filipp Zhmachenko (September – October) / Vitaliy Polenov (since October)

- 27th Army, led by Sergei Trofimenko

- 52nd Army, led by Konstantin Koroteev

- 2nd Air Army, led by Stepan Krasovsky

- Steppe Front (known as the 2nd Ukrainian Front after 20 October 1943), commanded by Ivan Konev

- Southwestern Front (known as the 3rd Ukrainian Front after 20 October 1943), commanded by Rodion Malinovsky

- Southern Front (known as the 4th Ukrainian Front after 20 October 1943), commanded by Fyodor Tolbukhin

German planning

editThe order to construct the Dnieper defence complex, known as "Ostwall" or "Eastern Wall", was issued on 11 August 1943 and began to be immediately executed.

Fortifications were erected along the length of the Dnieper. However, there was no hope of completing such an extensive defensive line in the short time available. Therefore, the completion of the "Eastern Wall" was not uniform in its density and depth of fortifications. Instead, they were concentrated in areas where a Soviet assault-crossing were most likely to be attempted, such as near Kremenchuk, Zaporizhia and Nikopol.

Additionally, on 7 September 1943, the SS forces and the Wehrmacht received orders to implement a scorched earth policy, by stripping the areas they had to abandon of anything that could be used by the Soviet war effort.

German organisation

edit- Luftflotte 2 (selected units) – Wolfram Freiherr von Richthofen

- (in Ukraine) Army Group South – Erich von Manstein

- 4th Panzer Army – Hermann Hoth

- 1st Panzer Army – Eberhard von Mackensen

- 8th Army – Otto Wohler

- 6th Army – Karl-Adolf Hollidt (transferred to Army Group A control)

- Luftflotte 4 – Wolfram Freiherr von Richthofen / Otto Deßloch (since September)

- (in Crimea) Army Group A – Ewald von Kleist

- Army Group Center – Günther von Kluge

- 2nd Army – Walter Weiß (took no part in the Dnieper battle after 3 October)

Description of the strategic operation

editInitial attack

editDespite a great superiority in numbers, the offensive was by no means easy. German opposition was ferocious and the fighting raged for every town and city. The Wehrmacht made extensive use of rear guards, leaving some troops in each city and on each hill, slowing the Soviet offensive.

Progress of the offensive

editThree weeks after the start of the offensive, and despite heavy losses on the Soviet side, it became clear that the Germans could not hope to contain the Soviet offensive in the flat, open terrain of the steppes, where the Red Army's numerical strength would prevail. Manstein asked for as many as 12 new divisions in the hope of containing the Soviet offensive – but German reserves were perilously thin.

On 15 September 1943, Hitler ordered Army Group South to retreat to the Dnieper defence line. The battle for Poltava was especially bitter. The city was heavily fortified and its garrison well prepared. After a few inconclusive days that greatly slowed down the Soviet offensive, Marshal Konev decided to bypass the city and rush towards the Dnieper. After two days of violent urban warfare, the Poltava garrison was overcome. Towards the end of September 1943, Soviet forces reached the lower part of the Dnieper.

Dnieper airborne operation

editThis section includes a list of references, related reading, or external links, but its sources remain unclear because it lacks inline citations. (September 2022) |

(The following is, largely, a synopsis of an account by Glantz[13] with support from an account by Staskov.[14])[verification needed]

Stavka detached the Central Front's 3rd Tank Army to the Voronezh Front to race the weakening Germans to the Dnieper, to save the wheat crop from the German scorched earth policy, and to achieve strategic or operational river bridgeheads before a German defence could stabilize there. The 3rd Tank Army, plunging headlong, reached the river on the night of 21–22 September and, on the 23rd, Soviet infantry forces crossed by swimming and by using makeshift rafts to secure small, fragile bridgeheads, opposed only by 120 German Cherkassy flak academy NCO candidates and the hard-pressed 19th Panzer Division Reconnaissance Battalion. Those forces were the only Germans within 60 km of the Dnieper loop. Only a heavy German air attack and a lack of bridging equipment kept Soviet heavy weaponry from crossing and expanding the bridgehead.

The Soviets, sensing a critical juncture, ordered a hasty airborne corps assault to increase the size of the bridgehead before the Germans could counterattack. On the 21st, the Voronezh Front's 1st, 3rd and 5th Guards Airborne Brigades got the urgent call to secure, on the 23rd, a bridgehead perimeter 15 to 20 km wide and 30 km deep on the Dnieper loop between Kaniv and Rzhishchev, while Front elements forced the river.

The arrival of personnel at the airfields was slow, necessitating, on the 23rd, a one-day delay and omission of 1st Brigade from the plan; consequent mission changes caused near chaos in command channels. Mission change orders finally got down to company commanders, on the 24th, just 15 minutes before their units, not yet provisioned with spades, anti-tank mines, or ponchos for the autumn night frosts, assembled on airfields. Owing to the weather, not all assigned aircraft had arrived at airfields on time (if at all). Further, most flight safety officers disallowed maximum loading of their aircraft. Given fewer aircraft (and lower than expected capacities), the master loading plan, ruined, was abandoned. Many radios and supplies got left behind. In the best case, it would take three lifts to deliver the two brigades. Units (still arriving by the overtaxed rail system), were loaded piecemeal onto returned aircraft, which were slow to refuel owing to the less-than-expected capacities of fuel trucks. Meanwhile, already-arrived troops changed planes, seeking earlier flights. Urgency and the fuel shortage prevented aerial assembly aloft. Most aircraft, as soon as they were loaded and fueled, flew in single file, instead of line abreast, to the dropping points. Assault waves became as intermingled as the units they carried.

As corps elements made their flights, troops (half of whom had never jumped, except from training towers) were briefed on drop zones, assembly areas and objectives only poorly understood by platoon commanders still studying new orders. Meanwhile, Soviet aerial photography, suspended for several days by bad weather, had missed the strong reinforcement of the area, early that afternoon. Non-combat cargo pilots ferrying 3rd Brigade through drizzle expected no resistance beyond river pickets but, instead, were met by anti-aircraft fire and flares from the 19th Panzer Division (only coincidentally transiting the drop zone, and just one of six divisions and other formations ordered, on the 21st, to fill the gap in front of the 3rd Tank Army). Lead aircraft, disgorging paratroopers over Dubari at 1930h, came under fire from elements of the 73rd Panzer Grenadier Regiment and division staff of 19th Panzer Division. Some paratroopers began returning fire and throwing grenades even before landing; trailing aircraft accelerated, climbed and evaded, dropping wide. Through the night, some pilots avoided flare-lit drop points entirely, and 13 aircraft returned to airfields without having dropped at all. Intending a 10 by 14 km drop over largely undefended terrain, the Soviets instead achieved a 30 by 90 km drop over the fastest mobile elements of two German corps.

On the ground, the Germans used white parachutes as beacons to hunt down and kill disorganized groups and to gather and destroy airdropped supplies. Supply bonfires, glowing embers, and multi-color starshells illuminated the battlefield. Captured documents gave the Germans enough knowledge of Soviet objectives to arrive at most of them before the disorganized paratroopers.

Back at the Soviet airfields, the fuel shortage allowed only 298 of 500 planned sorties, leaving corps anti-tank guns and 2,017 paratroops undelivered. Of 4,575 men dropped (seventy percent of the planned number, and just 1,525 from 5th Brigade), some 2,300 eventually assembled into 43 ad hoc groups, with missions abandoned as hopeless, and spent most of their time seeking supplies not yet destroyed by the Germans. Others joined with the nine partisan groups operating in the area. About 230 made it over (or out of) the Dnieper to Front units (or were originally dropped there). Most of the rest were captured that first night or killed the next day (although, on that first night, the 3rd Co, 73rd Panzer Grenadier Regiment, suffered heavy losses while annihilating about 150 paratroopers near Grushevo, some 3 km west of Dubari).

The Germans underestimated that 1,500 to 2,000 had dropped; they recorded 901 paratroops captured and killed in the first 24 hours. Thereafter, they largely ignored the Soviet paratroopers, to counterattack and truncate the Dnieper bridgeheads. The Germans deemed their anti-paratrooper operations completed by the 26th, although a modicum of opportunistic actions against garrisons, rail lines, and columns were conducted by remnants up to early November. For a lack of manpower to clear all areas, fighters in the area's forests would remain a minor threat.

The Germans called the operation a fundamentally sound idea ruined by the dilettantism of planners lacking expert knowledge (but praised individual paratroopers for their tenacity, bayonet skills, and deft use of broken ground in the sparsely wooded northern region). Stavka deemed this second (and, ultimately, last) corps drop a complete failure; lessons they knew they had already learned from their winter offensive corps drop at Viazma had not stuck. They would never trust themselves to try it again.

Soviet 5th Guards Airborne Brigade commander Sidorchuk, withdrawing to the forests south, eventually amassed a brigade-size command, half paratroops, half partisans; he obtained air supply, and assisted the 2nd Ukrainian Front over the Dnieper near Cherkassy to finally link up with Front forces on 15 November. After 13 more days of combat, the airborne element was evacuated, ending a harrowing two months. More than sixty percent never returned.

Assaulting the Dnieper

editThe first bridgehead on the Dnieper's western shore was established on 22 September 1943 at the confluence of the Dnieper and Pripyat rivers, in the northern part of the front. On 24 September, another bridgehead was created near Dniprodzerzhynsk, another on 25 September near Dnipropetrovsk and yet another on 28 September near Kremenchuk. By the end of the month, 23 bridgeheads were created on the western side, some of them 10 kilometers wide and 1–2 kilometres deep.

The crossing of the Dnieper was extremely difficult. Soldiers used every available floating device to cross the river, under heavy German fire and taking heavy losses. Once across, Soviet troops had to dig themselves into the clay ravines composing the Dnieper's western bank.

Securing the lodgements

editGerman troops soon launched heavy counterattacks on almost every bridgehead, hoping to annihilate them before heavy equipment could be transported across the river.

For instance, the Borodaevsk lodgement, mentioned by Marshal Konev in his memoirs, came under heavy armored attack and air assault. Bombers attacked both the lodgement and the reinforcements crossing the river. Konev complained at once about a lack of organization of Soviet air support, set up air patrols to prevent bombers from approaching the lodgements and ordered forward more artillery to counter tank attacks from the opposite shore. When Soviet aviation became more organized and hundreds of guns and Katyusha rocket launchers began firing, the situation started to improve and the bridgehead was eventually preserved.

Such battles were commonplace on every lodgement. Although all the lodgements were held, losses were terrible – at the beginning of October, most divisions were at only 25 to 50% of their nominal strength.

Lower Dnieper offensive

editBy mid-October, the forces accumulated on the lower Dnieper bridgeheads were strong enough to stage a first massive attack to definitely secure the river's western shore in the southern part of the front. Therefore, a vigorous attack was staged on the Kremenchuk-Dnipropetrovsk line. Simultaneously, a major diversion was conducted in the south to draw German forces away both from the Lower Dnieper and from Kiev.

At the end of the offensive, Soviet forces controlled a bridgehead 300 kilometers wide and up to 80 kilometers deep in some places. In the south, the Crimea was now cut off from the rest of the German forces. Any hope of stopping the Red Army on the Dnieper's east bank was lost.

Outcomes

editThe Battle of the Dnieper was another defeat for the Wehrmacht that required it to restabilize the front further west. The Red Army, which Hitler hoped to contain at the Dnieper, forced the Wehrmacht's defences. Kiev was recaptured and German troops lacked the forces to annihilate Soviet troops on the Lower Dnieper bridgeheads. The west bank was still in German hands for the most part, but both sides knew that it would not last for long.

Additionally, the Battle of the Dnieper demonstrated the strength of the Soviet partisan movement. The Rail War operation staged during September and October 1943 struck German logistics very hard, creating heavy supply issues.

Incidentally, between 28 November and 1 December 1943 the Tehran conference was held between Winston Churchill, Franklin D. Roosevelt, and Stalin. The Battle of the Dnieper, along with other major offensives staged in 1943, certainly gave Stalin a dominant position for negotiating with his Allies.

The Soviet success during this battle created the conditions for the follow-up Dnieper-Carpathian Offensive on the right-bank Ukraine, which was launched on 24 December 1943 from a bridgehead west of Kiev that was secured during this battle.[15] The offensive brought the Red Army from the Dnieper all the way to Galicia (Poland), Carpathian Mountains and Romania, with Army Group South being split into two parts- north and south of Carpathians.

Soviet operational phases

editFrom a Soviet operational point of view, the battle was broken down into a number of different phases and offensives.

The first phase of the battle :

- Chernigov-Poltava Strategic Offensive 26 August 1943 – 30 September 1943 (Central, Voronezh and Steppe fronts)

- Chernigov-Pripyat Offensive 26 August – 30 September 1943

- Sumy–Priluky Offensive 26 August – 30 September 1943

- Poltava-Kremenchug Offensive 26 August – 30 September 1943

- Donbass Strategic Offensive 13 August – 22 September 1943 (Southwestern and Southern fronts)

- Dnieper airborne assault 24 September – 24 November 1943

The second phase of the operation includes :

- Lower Dnieper Offensive 26 September – 20 December 1943

- Melitopol Offensive 26 September – 5 November 1943

- Zaporizhia Offensive 10–14 October 1943

- Kremenchug-Pyatikhatki Offensive 15 October – 3 November 1943

- Dnepropetrovsk Offensive 23 October – 23 December 1943

- Krivoi Rog Offensive 14–21 November 1943

- Apostolovo Offensive 14 November – 23 December 1943

- Nikopol Offensive 14 November – 31 December 1943

- Aleksandriia-Znamenka Offensive 22 November – 9 December 1943

- Krivoi Rog Offensive 10–19 December 1943

- Kiev Strategic Offensive Operation (October) (1–24 October 1943)

- Chernobyl-Radomysl Offensive Operation (1–4 October 1943)

- Chernobyl-Gornostaipol Defensive Operation (3–8 October 1943)

- Lyutezh Offensive Operation (11–24 October 1943)

- Bukrin Offensive Operation (12–15 October 1943)

- Bukrin Offensive Operation (21–24 October 1943)

- Kiev Strategic Offensive 3–13 November 1943

- Rauss' November 1943 counterattack

- Kiev Strategic Defensive 13 November – 22 December 1943

References

editCitations

edit- ^ Edwards, Robert (15 August 2018). The Eastern Front: The Germans and Soviets at War in World War II. Rowman & Littlefield. ISBN 978-0-8117-6784-2.

- ^ Frieser, Karl-Heinz. The Eastern Front 1943-1944: The War in the East and on the Neighbouring Fronts. Oxford University Press, 2017, p. 356.

- ^ a b c d Frieser et al. 2007, p. 343.

- ^ OKH Org.Abt. I Nr. I/5645/43 g.Kdos. Iststärke des Feldheeres Stand 1.11.43. NARA T78, R528, F768.

- ^ Oberkommando des Heeres. Geheime Kommandosache. Panzerlage der Heeresgruppe Süd. Stand am 10 November 1943. Bundesarchiv-Militärarchiv (BA-MA) RH 10/52, fol. 80.

- ^ Frieser, Karl-Heinz. Germany and the Second World War: Volume VIII: The Eastern Front 1943-1944: The War in the East and on the Neighbouring Fronts. Oxford University Press, 2017, p. 364.

- ^ OKH Org.Abt. I Nr. I/5645/43 g.Kdos. Iststärke des Feldheeres Stand 1.11.43. NARA T78, R528, F770.

- ^ Кривошеев, Г.Ф. (2001). "Россия и СССР в войнах XX века: Потери вооруженных сил". ОЛМА-ПРЕСС.

- ^ Frieser et al. 2007, p. 379.

- ^ Forczyk, Robert. The Dnepr 1943: Hitler's Eastern Rampart Crumbles. Osprey Publishing 2016, p. 91.

- ^ Forczyk, Robert. The Dnepr 1943: Hitler's Eastern Rampart Crumbles. Osprey Publishing 2016, p. 91.

- ^ Military Review. Command and General Staff School. 1993. p. 2-PA75.

- ^ The History of Soviet Airborne Forces, Chapter 8, Across The Dnieper (September 1943), by David M. Glantz, Cass, 1994. (portions online)

- ^ 1943 Dnepr airborne operation: lessons and conclusions Military Thought, July 2003, by Nikolai Viktorovich Staskov. (online) See ref at Army (Soviet Army) under 40th Army entry.

- ^ Грылев А.Н. Днепр-Карпаты-Крым. Освобождение Правобережной Украины и Крыма в 1944 году. Москва: Наука, 1970, p. 19.

Bibliography

editThis article includes a list of general references, but it lacks sufficient corresponding inline citations. (February 2008) |

- Frieser, Karl-Heinz; Schmider, Klaus; Schönherr, Klaus; Schreiber, Gerhard; Ungváry, Kristián; Wegner, Bernd (2007). Die Ostfront 1943/44 – Der Krieg im Osten und an den Nebenfronten [The Eastern Front 1943–1944: The War in the East and on the Neighbouring Fronts]. Das Deutsche Reich und der Zweite Weltkrieg (Germany and the Second World War) (in German). Vol. VIII. München: Deutsche Verlags-Anstalt. ISBN 978-3-421-06235-2.

- David M. Glantz, Jonathan M. House, When Titans Clashed: How the Red Army stopped Hitler, University Press of Kansas, 1995

- Nikolai Shefov, Russian fights, Lib. Military History, Moscow, 2002

- History of Great Patriotic War, 1941–1945. Moscow, 1963

- John Erickson, Barbarossa: The Axis and the Allies, Edinburgh University Press, 1994

- Harrison, Richard. (2018) The Battle of the Dnepr: The Red Army's Forcing of the East Wall, September–December 1943. Helion and Company. ISBN 978-1912174171

- Marshal Konev, Notes of a front commander, Science, Moscow, 1972.

- Erich von Manstein, Lost Victories, Moscow, 1957.