Dissolution of the Peru–Bolivian Confederation

This article needs additional citations for verification. (March 2023) |

The dissolution of the Peru–Bolivian Confederation was the process of internal disintegration within the Peru–Bolivian Confederation which resulted in the end of the country's and its confederate government's existence as a sovereign state, being succeeded by Bolivia and a unified Peruvian state.

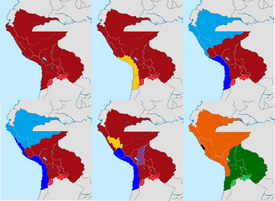

- Peru-BoliviaControlled by the United Restoration ArmyNew Peruvian StateNew Bolivian StateControlled by the United Restoration Army during the restorationDe facto borders after the dissolutionDisputed between Peru-Bolivia and Argentina

The disintegration was related to the conflict of interest between the Confederation and the Republic of Chile,[1][2] as well as the friction inherited by the Bolivian side with the latter. Unlike Gran Colombia, which was created in 1819 and disappeared in 1831, the dissolution of the Confederation was marked by a certain tranquility and tolerance for a certain period of one year when Agustín Gamarra himself began his military campaign in Bolivian territory, resulting in his death and the signing of the Treaty of Puno,[3][4] which put an end to all ideas of union, annexation, confederation or federation between the two countries at least during the beginning of the 19th century.

Background

editAfter the creation of the Confederation by Andrés de Santa Cruz, protests began by opposition and nationalist sides of both nations, causing massive deportations to Europe or other countries in the Americas, several of them as political refugees.[5][6] Abroad, Andrés de Santa Cruz also had opponents, especially in Chile, such as Minister Diego Portales[7] and Chilean President Joaquín Prieto.[2]

In one of his letters, Portales spoke about the Peru-Bolivian Confederation and its "unacceptable" existence:

Chile's position on the Peru-Bolivian Confederation is untenable. It cannot be tolerated either by the people or by the government because it is tantamount to their suicide. We cannot look without concern and the greatest alarm, the existence of two peoples, and that, in the long run, due to the community of origin, language, habits, religion, ideas, customs, will form, as is natural, a single nucleus. United, these two States, even if only momentarily, will always be more than Chile in all order of issues and circumstances [...] The confederation must disappear forever from the American scene due to its geographical extension; for its larger white population; for the joint riches of Peru and Bolivia, scarcely exploited now; for the dominance that the new organization would try to exercise in the Pacific by taking it away from us; by the greater number of enlightened white people, closely linked to the families of Spanish influence that are in Lima; for the greater intelligence of its public men, although of less character than the Chileans; For all these reasons, the Confederation would drown Chile before very long [...] The naval forces must operate before the military, delivering decisive blows. We must dominate forever in the Pacific: this must be their maxim now, and I hope it will be Chile's forever [...].

— Letter from Diego Portales to Blanco Encalada, September 10, 1836.[8]

Peruvians opposed to the Confederation such as Agustín Gamarra,[6] Ramón Castilla or Antonio Gutiérrez de la Fuente accepted the alliance with Chile to remove Andrés de Santa Cruz and return the respective united nations to their normal state.

Dissolution

editDuring its existence, the government of Santa Cruz saw the rise of different parallel governments.

Peruvian Republic (1837)

editDuring the first expedition of the United Restoration Army, the restorers disembarked on Islay and immediately entered the city of Arequipa, where a council proclaimed De La Fuente the Supreme Chief[7] on October 17, 1837, a position he held only nominally. Cornered by Santa Cruz's Confederate troops, the restorers were forced to sign the Paucarpata Peace Treaty on November 17, 1837. La Fuente returned to Chile along with the rest of the Chilean-Peruvian expedition.[9]

Peruvian Republic (1838–1839)

editSanta Cruz appointed Luis José de Orbegoso as president of North Peru from August 21, 1837 to September 1, 1838. However, Orbegoso remained in office when Santa Cruz himself appointed Marshal José de la Riva-Agüero as his replacement on July 11, 1838, a position that he held, precariously, until January 24, 1939.

Domingo Nieto remained faithful to the legal authority of Orbegoso, however, he did not compromise with the Confederate regime and put himself at the service of the will of the people. Finally, he decided to rise up against Santa Cruz and proclaimed the freedom of the territory of the North-Peruvian State as the Peruvian Republic, on July 30, 1838.[10] Orbegoso, undecided at first, ended up joining that cause and General Juan Francisco de Vidal.[11]

General Nieto, made forays through the north with dispatches from the Supreme Chief issued by Orbegoso, sharing the position between the two.[12]

Santa Cruz, through his cunning, managed to maintain the rebel state as an autonomous republic by turning it against the restorative allies, causing the imminent invasion of northern Peru. The restorers advanced on Lima and despite the opposition of Nieto (who rightly feared the numerical superiority of the enemy) the Battle of Portada de Guías took place on August 21, 1838 in which the Orbegosistas were defeated.[13][14]

After the conquest of northern Peru by the restorers, Agustín Gamarra was proclaimed as provisional president. A year later, the confederates launched a reconquest campaign in the north, causing the restorers to flee and re-annexing the territory of northern Peru.[15]

Peruvian Republic (1838–1841)

editThe Peruvian Republic, presided over by Agustín Gamarra, was the second Peruvian provisional government, backed by the United Restoration Army, which had the objective of restoring Peru as an independent unit.[6]

The seven presidents

editBy September 1838, the Confederation's stability had collapsed, as Peru (i.e. North and South Peru) was under the de jure control of seven different presidents at one time, who held varying degrees of power: Santa Cruz, who was the Supreme Protector; Gamara, the restorationist president; Orbegoso, leader of the seccessionist North Peruvian state; José de la Riva Agüero, who replaced Orbegoso, being appointed by Santa Cruz; Pío de Tristán, president of South Peru; Domingo Nieto, in the north; and Juan Francisco de Vidal in Huaylas.[12]

Consequences

editAfter the disunity between Peru and Bolivia and the fatal outcome of the war, both countries distanced themselves and began the process of delimiting their borders until the beginning of the Guano Era and the commercial rapprochement of these countries with Chile. In 1873, Peru and Bolivia sealed the Treaty of Defensive Alliance to protect their commercial interests.

In Peru, after the war and the defeat of the Confederation in the Battle of Yungay, the new Peruvian provisional government of Agustín Gamarra, with the protection of the Chilean Army,[16] declared the dissolution of the Confederation on August 25, 1839, initiating the so-called national restoration and creating the New Constituent General Congress of Peru. He substituted the confederate organization with a unitary organization, withdrew Bolivian public workers, and rebuilt Peru's international relations.

References

edit- ^ Tamayo 1985, p. 254.

- ^ a b Basadre 2014, p. 140.

- ^ Novak, Fabián; Namihas, Sandra (2013). Las Relaciones entre el Perú y Bolivia (1826–2013). Konrad Adenauer Foundation. p. 46. ISBN 978-9972-671-18-0.

- ^ Preliminary Treaty of Peace and Friendship between Peru and Bolivia (PDF). Congress of Peru. 1842.

- ^ Tamayo 1985, p. 253.

- ^ a b c Tauro del Pino, Alberto (2001). Enciclopedia ilustrada del Perú: CAN-CHO (in Spanish). Lima: Empresa Editora El Comercio S. A. pp. 544–545. ISBN 9972401499.

- ^ a b Basadre 2014, p. 135.

- ^ Villalobos, Sergio (2001). Chile y su historia (in Spanish). Editorial Universitaria. pp. 241–242. ISBN 9789561115293.

- ^ Basadre 2014, p. 135–136.

- ^ Basadre 2014, p. 139.

- ^ Vargas Sifuentes, José Luis (2019-11-16). "Los siete presidentes". El Peruano.

- ^ a b Basadre 2014, p. 145.

- ^ Tamayo 1985, p. 256.

- ^ Basadre 2014, p. 142.

- ^ Tamayo 1985, p. 255–256.

- ^ Molina Hernández, Jorge Javier (2009). Vida de un soldado: desde la Toma de Valdivia (1820) a la victoria de Yungay (1839) (in Spanish). RIL Ediciones. pp. 232–253. ISBN 978-9562846769.

Bibliography

edit- Basadre Grohmann, Jorge (2014). Historia de la República del Perú [1822–1933]. Vol. 2. El Comercio. ISBN 978-612-306-353-5.

- Tamayo Herrera, José (1985). Nuevo Compendio de Historia del Perú. Editorial Lumen.