Digitization[1] is the process of converting information into a digital (i.e. computer-readable) format.[2] The result is the representation of an object, image, sound, document, or signal (usually an analog signal) obtained by generating a series of numbers that describe a discrete set of points or samples.[3] The result is called digital representation or, more specifically, a digital image, for the object, and digital form, for the signal. In modern practice, the digitized data is in the form of binary numbers, which facilitates processing by digital computers and other operations, but digitizing simply means "the conversion of analog source material into a numerical format"; the decimal or any other number system can be used instead.[4]

Digitization is of crucial importance to data processing, storage, and transmission, because it "allows information of all kinds in all formats to be carried with the same efficiency and also intermingled."[5] Though analog data is typically more stable, digital data has the potential to be more easily shared and accessed and, in theory, can be propagated indefinitely without generation loss, provided it is migrated to new, stable formats as needed.[6] This potential has led to institutional digitization projects designed to improve access and the rapid growth of the digital preservation field.[7]

Sometimes digitization and digital preservation are mistaken for the same thing. They are different, but digitization is often a vital first step in digital preservation.[8] Libraries, archives, museums, and other memory institutions digitize items to preserve fragile materials and create more access points for patrons.[9] Doing this creates challenges for information professionals and solutions can be as varied as the institutions that implement them.[10] Some analog materials, such as audio and video tapes, are nearing the end of their life cycle, and it is important to digitize them before equipment obsolescence and media deterioration makes the data irretrievable.[11]

There are challenges and implications surrounding digitization including time, cost, cultural history concerns, and creating an equitable platform for historically marginalized voices.[12] Many digitizing institutions develop their own solutions to these challenges.[9]

Mass digitization projects have had mixed results over the years, but some institutions have had success even if not in the traditional Google Books model.[13] Although e-books have undermined the sales of their printed counterparts, a study from 2017 indicated that the two cater to different audiences and use-cases.[14] In a study of over 1400 university students it was found that physical literature is more apt for intense studies while e-books provide a superior experience for leisurely reading.[14]

Technological changes can happen often and quickly, so digitization standards are difficult to keep updated. Professionals in the field can attend conferences and join organizations and working groups to keep their knowledge current and add to the conversation.[15]

Process

editThe term digitization is often used when diverse forms of information, such as an object, text, sound, image, or voice, are converted into a single binary code. The core of the process is the compromise between the capturing device and the player device so that the rendered result represents the original source with the most possible fidelity, and the advantage of digitization is the speed and accuracy in which this form of information can be transmitted with no degradation compared with analog information.

Digital information exists as one of two digits, either 0 or 1. These are known as bits (a contraction of binary digits) and the sequences of 0s and 1s that constitute information are called bytes.[16]

Analog signals are continuously variable, both in the number of possible values of the signal at a given time, as well as in the number of points in the signal in a given period of time. However, digital signals are discrete in both of those respects – generally a finite sequence of integers – therefore a digitization can, in practical terms, only ever be an approximation of the signal it represents.

Digitization occurs in two parts:

- Discretization

- The reading of an analog signal A, and, at regular time intervals (frequency), sampling the value of the signal at the point. Each such reading is called a sample and may be considered to have infinite precision at this stage;

- Quantization

- Samples are rounded to a fixed set of numbers (such as integers), a process known as quantization.

In general, these can occur at the same time, though they are conceptually distinct.

A series of digital integers can be transformed into an analog output that approximates the original analog signal. Such a transformation is called a digital-to-analog conversion. The sampling rate and the number of bits used to represent the integers combine to determine how close such an approximation to the analog signal a digitization will be.

Examples

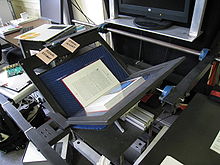

editThe term is used to describe, for example, the scanning of analog sources (such as printed photos or taped videos) into computers for editing, 3D scanning that creates 3D modeling of an object's surface, and audio (where sampling rate is often measured in kilohertz) and texture map transformations. In this last case, as in normal photos, the sampling rate refers to the resolution of the image, often measured in pixels per inch.

Digitizing is the primary way of storing images in a form suitable for transmission and computer processing, whether scanned from two-dimensional analog originals or captured using an image sensor-equipped device such as a digital camera, tomographical instrument such as a CAT scanner, or acquiring precise dimensions from a real-world object, such as a car, using a 3D scanning device.[17]

Digitizing is central to making digital representations of geographical features, using raster or vector images, in a geographic information system, i.e., the creation of electronic maps, either from various geographical and satellite imaging (raster) or by digitizing traditional paper maps or graphs (vector).[citation needed]

"Digitization" is also used to describe the process of populating databases with files or data. While this usage is technically inaccurate, it originates with the previously proper use of the term to describe that part of the process involving digitization of analog sources, such as printed pictures and brochures, before uploading to target databases.[3]

Digitizing may also be used in the field of apparel, where an image may be recreated with the help of embroidery digitizing software tools and saved as embroidery machine code. This machine code is fed into an embroidery machine and applied to the fabric. The most supported format is DST file. Apparel companies also digitize clothing patterns.[citation needed][18]

History

edit- 1957 The Standards Electronic Automatic Computer (SEAC) was invented.[19] That same year, Russell Kirsch used a rotating drum scanner and photomultiplier connected to SEAC to create the first digital image (176x176 pixels) from a photo of his infant son.[20][21] This image was stored in SEAC memory via a staticizer and viewed via a cathode ray oscilloscope.[22][21]

- 1971 Invention of Charge-Coupled Devices that made conversion from analog data to a digital format easy.[19]

- 1986 work started on the JPEG format.[19]

- 1990s Libraries began scanning collections to provide access via the world wide web.[13]

Analog signals to digital

editAnalog signals are continuous electrical signals; digital signals are non-continuous. Analog signals can be converted to digital signals by using an analog-to-digital converter.[23]

The process of converting analog to digital consists of two parts: sampling and quantizing. Sampling measures wave amplitudes at regular intervals, splits them along the vertical axis, and assigns them a numerical value, while quantizing looks for measurements that are between binary values and rounds them up or down.[24]

Nearly all recorded music has been digitized, and about 12 percent of the 500,000+ movies listed on the Internet Movie Database are digitized and were released on DVD.[25][26]

Digitization of home movies, slides, and photographs is a popular method of preserving and sharing personal multimedia. Slides and photographs may be scanned quickly using an image scanner, but analog video requires a video tape player to be connected to a computer while the item plays in real time.[27][28] Slides can be digitized quicker with a slide scanner such as the Nikon Coolscan 5000ED.[29]

Another example of digitization is the VisualAudio process developed by the Swiss Fonoteca Nazionale in Lugano, by scanning a high resolution photograph of a record, they are able to extract and reconstruct the sound from the processed image.[30]

Digitization of analog tapes before they degrade, or after damage has already occurred, can rescue the only copies of local and traditional cultural music for future generations to study and enjoy.[31][32]

Analog texts to digital

editAcademic and public libraries, foundations, and private companies like Google are scanning older print books and applying optical character recognition (OCR) technologies so they can be keyword searched, but as of 2006, only about 1 in 20 texts had been digitized.[3][33] Librarians and archivists are working to increase this statistic and in 2019 began digitizing 480,000 books published between 1923 and 1964 that had entered the public domain.[34]

Unpublished manuscripts and other rare papers and documents housed in special collections are being digitized by libraries and archives, but backlogs often slow this process and keep materials with enduring historical and research value hidden from most users (see digital libraries).[35] Digitization has not completely replaced other archival imaging options, such as microfilming which is still used by institutions such as the National Archives and Records Administration (NARA) to provide preservation and access to these resources.[36][37]

While digital versions of analog texts can potentially be accessed from anywhere in the world, they are not as stable as most print materials or manuscripts and are unlikely to be accessible decades from now without further preservation efforts, while many books manuscripts and scrolls have already been around for centuries.[31] However, for some materials that have been damaged by water, insects, or catastrophes, digitization might be the only option for continued use.[31]

Library preservation

editIn the context of libraries, archives, and museums, digitization is a means of creating digital surrogates of analog materials, such as books, newspapers, microfilm and videotapes, offers a variety of benefits, including increasing access, especially for patrons at a distance; contributing to collection development, through collaborative initiatives; enhancing the potential for research and education; and supporting preservation activities.[38] Digitization can provide a means of preserving the content of the materials by creating an accessible facsimile of the object in order to put less strain on already fragile originals. For sounds, digitization of legacy analog recordings is essential insurance against technological obsolescence.[39] A fundamental aspect of planning digitization projects is to ensure that the digital files themselves are preserved and remain accessible;[40] the term "digital preservation," in its most basic sense, refers to an array of activities undertaken to maintain access to digital materials over time.[41]

The prevalent Brittle Books issue facing libraries across the world is being addressed with a digital solution for long term book preservation.[42] Since the mid-1800s, books were printed on wood-pulp paper, which turns acidic as it decays. Deterioration may advance to a point where a book is completely unusable. In theory, if these widely circulated titles are not treated with de-acidification processes, the materials upon those acid pages will be lost. As digital technology evolves, it is increasingly preferred as a method of preserving these materials, mainly because it can provide easier access points and significantly reduce the need for physical storage space.

Cambridge University Library is working on the Cambridge Digital Library, which will initially contain digitised versions of many of its most important works relating to science and religion. These include examples such as Isaac Newton's personally annotated first edition of his Philosophiæ Naturalis Principia Mathematica[43] as well as college notebooks[44][45] and other papers,[46] and some Islamic manuscripts such as a Quran[47] from Tipu Sahib's library.

Google, Inc. has taken steps towards attempting to digitize every title with "Google Book Search".[48] While some academic libraries have been contracted by the service, issues of copyright law violations threaten to derail the project.[49] However, it does provide – at the very least – an online consortium for libraries to exchange information and for researchers to search for titles as well as review the materials.

Digitization versus digital preservation

editDigitizing something is not the same as digitally preserving it.[8] To digitize something is to create a digital surrogate (copy or format) of an existing analog item (book, photograph, or record) and is often described as converting it from analog to digital, however both copies remain.[4][50] An example would be scanning a photograph and having the original piece in a photo album and a digital copy saved to a computer. This is essentially the first step in digital preservation which is to maintain the digital copy over a long period of time and making sure it remains authentic and accessible.[51][8][6]

Digitization is done once with the technology currently available, while digital preservation is more complicated because technology changes so quickly that a once popular storage format may become obsolete before it breaks.[6] An example is a 5 1/4" floppy drive, computers are no longer made with them and obtaining the hardware to convert a file stored on 5 1/4" floppy disc can be expensive. To combat this risk, equipment must be upgraded as newer technology becomes affordable (about 2 to 5 years), but before older technology becomes unobtainable (about 5 to 10 years).[52][6]

Digital preservation can also apply to born-digital material, such as a Microsoft Word document or a social media post.[53] In contrast, digitization only applies exclusively to analog materials. Born-digital materials present a unique challenge to digital preservation not only due to technological obsolescence but also because of the inherently unstable nature of digital storage and maintenance.[6] Most websites last between 2.5 and 5 years, depending on the purpose for which they were designed.[54]

The Library of Congress provides numerous resources and tips for individuals looking to practice digitization and digital preservation for their personal collections.[55]

Digital reformatting

editDigital reformatting is the process of converting analog materials into a digital format as a surrogate of the original. The digital surrogates perform a preservation function by reducing or eliminating the use of the original. Digital reformatting is guided by established best practices to ensure that materials are being converted at the highest quality.

Digital reformatting at the Library of Congress

editThe Library of Congress has been actively reformatting materials for its American Memory project and developed best standards and practices pertaining to book handling during the digitization process, scanning resolutions, and preferred file formats.[56] Some of these standards are:

- The use of ISO 16067-1 and ISO 16067-2 standards for resolution requirements.

- Recommended 400 ppi resolution for OCR'ed printed text.

- The use of 24-bit color when color is an important attribute of a document.

- The use of the scanning device's maximum resolution for digitally reproducing photographs

- TIFF as the standard file format.

- Attachment of descriptive, structural, and technical metadata to all digitized documents.

A list of archival standards for digital preservation can be found on the ARL website.[57]

The Library of Congress has constituted a Preservation Digital Reformatting Program.[58] The Three main components of the program include:

- Selection Criteria for digital reformatting

- Digital reformatting principles and specifications

- Life cycle management of LC digital data

Audio digitization and reformatting

editAudio media offers a rich source of historic ethnographic information, with the earliest forms of recorded sound dating back to 1890.[59] According to the International Association of Sound and Audiovisual Archives (IASA), these sources of audio data, as well as the aging technologies used to play them back, are in imminent danger of permanent loss due to degradation and obsolescence.[60] These primary sources are called “carriers” and exist in a variety of formats, including wax cylinders, magnetic tape, and flat discs of grooved media, among others. Some formats are susceptible to more severe, or quicker, degradation than others. For instance, lacquer discs suffer from delamination. Analog tape may deteriorate due to sticky shed syndrome.[61]

Archival workflow and file standardization have been developed to minimize loss of information from the original carrier to the resulting digital file as digitization is underway. For most at-risk formats (magnetic tape, grooved cylinders, etc.), a similar workflow can be observed. Examination of the source carrier will help determine what, if any, steps need to be taken to repair material prior to transfer. A similar inspection must be undertaken for the playback machines. If satisfactory conditions are met for both carrier and playback machine, the transfer can take place, moderated by an analog-to-digital converter.[62] The digital signal is then represented visually for the transfer engineer by a digital audio workstation, like Audacity, WaveLab, or Pro Tools. Reference access copies can be made at smaller sample rates. For archival purposes, it is standard to transfer at a sample rate of 96 kHz and a bit depth of 24 bits per channel.[59]

Challenges

editMany libraries, archives, museums, and other memory institutions, struggle with catching up and staying current regarding digitization and the expectation that everything should already be online.[63][64] The time spent planning, doing the work, and processing the digital files along with the expense and fragility of some materials are some of the most common.

Time spent

editDigitization is a time-consuming process, even more so when the condition or format of the analog resources requires special handling.[65] Deciding what part of a collection to digitize can sometimes take longer than digitizing it in its entirety.[66] Each digitization project is unique and workflows for one will be different from every other project that goes through the process, so time must be spent thoroughly studying and planning each one to create the best plan for the materials and the intended audience.[67]

Expense

editCost of equipment, staff time, metadata creation, and digital storage media make large scale digitization of collections expensive for all types of cultural institutions.[68]

Ideally, all institutions want their digital copies to have the best image quality so a high-quality copy can be maintained over time.[68] In the mid-long term, digital storage would be regarded as the more expensive part to maintain the digital archives due to the increasing number of scanning requests.[69] However, smaller institutions may not be able to afford such equipment or manpower, which limits how much material can be digitized, so archivists and librarians must know what their patrons need and prioritize digitization of those items.[70] To help the information institutions to better decide the archives worth of digitization, Casablancas and other researchers used a proposed model to investigate the impact of different digitization strategies on the decrease in access requests in the archival and library reading rooms.[69] Often the cost of time and expertise involved with describing materials and adding metadata is more than the digitization process.[31]

Fragility of materials

editSome materials, such as brittle books, are so fragile that undergoing the process of digitization could damage them irreparably.[66][70] Despite potential damage, one reason for digitizing fragile materials is because they are so heavily used that creating a digital surrogate will help preserve the original copy long past its expected lifetime and increase access to the item.[9]

Copyright

editCopyright is not only a problem faced by projects like Google Books, but by institutions that may need to contact private citizens or institutions mentioned in archival documents for permission to scan the items for digital collections.[68] It can be time consuming to make sure all potential copyright holders have given permission, but if copyright cannot be determined or cleared, it may be necessary to restrict even digital materials to in library use.[31][68]

Solutions

editInstitutions can make digitization more cost-effective by planning before a project begins, including outlining what they hope to accomplish and the minimum amount of equipment, time, and effort that can meet those goals.[9] If a budget needs more money to cover the cost of equipment or staff, an institution might investigate if grants are available.[9][68]

Collaboration

editCollaborations between institutions have the potential to save money on equipment, staff, and training as individual members share their equipment, manpower, and skills rather than pay outside organizations to provide these services.[10] Collaborations with donors can build long-term support of current and future digitization projects.[71][64]

Outsourcing

editOutsourcing can be an option if an institution does not want to invest in equipment but since most vendors require an inventory and basic metadata for materials, this is not an option for institutions hoping to digitize without processing.[64][68]

Non-traditional staffing

editMany institutions have the option of using volunteers, student employees, or temporary employees on projects. While this saves on staffing costs, it can add costs elsewhere such as on training or having to re-scan items due to poor quality.[64][72]

MPLP

editOne way to save time and resources is by using the More Product, Less Process (MPLP) method to digitize materials while they are being processed.[63] Since GLAM (Galleries, Libraries, Archives, and Museums) institutions are already committed to preserving analog materials from special collections, digital access copies do not need to be high-resolution preservation copies, just good enough to provide access to rare materials.[66] Sometimes institutions can get by with 300 dpi JPGs rather than a 600 dpi TIFF for images, and a 300 dpi grayscale scan of a document rather than a color one at 600 dpi.[68][73]

Digitizing marginalized voices

editDigitization can be used to highlight voices of historically marginalized peoples and add them to the greater body of knowledge. Many projects, some community archives created by members of those groups, are doing this in a way that supports the people, values their input and collaboration, and gives them a sense of ownership of the collection.[74][12] Examples of projects are Gi-gikinomaage-min and the South Asian American Digital Archive (SAADA).

Gi-gikinomaage-min

editGi-gikinomaage-min is Anishinaabemowin for "We are all teachers" and its main purpose is "to document the history of Native Americans in Grand Rapids, Michigan."[75] It combines new audio and video oral histories with digitized flyers, posters, and newsletters from Grand Valley State University's analog collections.[75] Although not entirely a newly digitized project, what was created also added item-level metadata to enhance context. At the start, collaboration between several university departments and the Native American population was deemed important and remained strong throughout the project.[75]

SAADA

editThe South Asian American Digital Archive (SAADA) has no physical building, is entirely digital and everything is handled by volunteers.[76] This archive was started by Michelle Caswell and Samip Mallick and collects a broad variety of materials "created by or about people residing in the United States who trace their heritage to Bangladesh, Bhutan, India, Maldives, Nepal, Pakistan, Sri Lanka, and the many South Asian diaspora communities across the globe."[76] (Caswell, 2015, 2). The collection of digitized items includes private, government, and university held materials.[76]

Black Campus Movement Collection (BCM)

editKent State University began its BCM collection when it acquired the papers of African American alumnus Lafayette Tolliver, which included about 1,000 photographs that chronicled the black student experience at Kent State from 1968-1971.[12] The collection continues to add materials from the 1960s up to and including the current student body and several oral histories have been added since it debuted.[12] When digitizing the items, it was necessary to work with alumni to create descriptions for the images. This collaboration created changes in local controlled vocabularies the libraries used to create metadata for the images.[12]

Mass digitization

editThe expectation that everything should be online has led to mass digitization practices, but it is an ongoing process with obstacles that have led to alternatives.[66] As new technology makes automated scanning of materials safer for materials and decreases need for cropping and de-skewing, mass digitization should be able to increase.[66]

Obstacles

editDigitization can be a physically slow process involving selection and preparation of collections that can take years if materials need to be compared for completeness or are vulnerable to damage.[77] Price of specialized equipment, storage costs, website maintenance, quality control, and retrieval system limitations all add to the problems of working on a large scale.[77]

Data privacy and security

editDigitization presents significant challenges related to data privacy and security.[78] As organizations increasingly depend on electronic databases and information systems, their vulnerability to security threats also rises.[79] The risk of data loss rises and cyberattacks can result in significant financial losses and damage the company’s reputation .[79] Therefore, there is a need for better cybersecurity measures and protection of data security and privacy to decrease the risks associated with digitization.[79]

Successes

editDigitization on demand

editScanning materials as users ask for them, provides copies for others to use and cuts down on repeated copying of popular items. If one part of a folder, document, or book is asked for, scanning the entire object can save time in the future by already having the material access if someone else needs the material.[66][77] Digitizing on demand can increase volume because time spent on selection and prep has been used on scanning instead.[77]

Google Books

editFrom the start, Google has concentrated on text rather than images or special collections.[77] Although criticized in the past for poor image quality, selection practices, and lacking long-term preservation plans, their focus on quantity over quality has enabled Google to digitize more books than other digitizers.[66][77]

Standards

editDigitization is not a static field and standards change with new technology, so it is up to digitization managers to stay current with new developments.[15] Although each digitization project is different, common standards in formats, metadata, quality, naming, and file storage should be used to give the best chance of interoperability and patron access.[80] As digitization is often the first step in digital preservation, questions about how to handle digital files should be addressed in institutional standards.[7]

A standard for still images adapted from the Smithsonian digitization standards might include the following:[81]

| Still Image Digitization Standards | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Filename format | Analog Material Type | Color or B&W | Resolution of Scan | RGB Setting for Scan | Digital File Format | File Compression | Metadata |

| YYYYMMDD_CollectionID#_Image# | 35 mm print | Color | 600 ppi | 24 bit; 8 bits per color channel | TIFF | None | Follow Local Controlled Vocabularies and LC SH and NAF |

| YYYYMMDD_CollectionID#_Image# | 35 mm slide | Color | 1400 ppi | 24 Bit; 8 bits per color channel | TIFF | None | Follow Local Controlled Vocabularies and LC SH and NAF |

| YYYYMMDD_CollectionID#_Image# | microform | B&W | 300 ppi | 24 Bit | TIFF | None | Follow Local Controlled Vocabularies and LC SH and NAF |

Resources to create local standards are available from the Society of American Archivists, the Smithsonian, and the Northeast Document Conservation Center.[82][81][15]

Implications

editCultural heritage concerns

editDigitization of community archives by indigenous and other marginalized people has led to traditional memory institutions reassessing how they digitize and handle objects in their collections that may have ties to these groups.[74] The topics they are rethinking are varied and include how items are chosen for digitization projects, what metadata to use to convey proper context to be retrievable by the groups they represent, and whether an item should be accessed by the world or just those who the groups originally intended to have access, such as elders.[74] Many navigate these concerns by collaborating with the communities they seek to represent through their digitized collections.[74]

Lean philosophy

editThe broad use of internet and the increasing popularity of lean philosophy has also increased the use and meaning of "digitizing" to describe improvements in the efficiency of organizational processes. Lean philosophy refers to the approach which considers any use of time and resources, which does not lead directly to creating a product, as waste and therefore a target for elimination. This will often involve some kind of Lean process in order to simplify process activities, with the aim of implementing new "lean and mean" processes by digitizing data and activities. Digitization can help to eliminate time waste by introducing wider access to data, or by the implementation of enterprise resource planning systems.

Fiction

editWorks of science-fiction often include the term digitize as the act of transforming people into digital signals and sending them into digital technology. When that happens, the people disappear from the real world and appear in a virtual world (as featured in the cult film Tron, the animated series Code: Lyoko, or the late 1980s live-action series Captain Power and the Soldiers of the Future). In the video game Beyond Good & Evil, the protagonist's holographic friend digitizes the player's inventory items. One Super Friends cartoon episode showed Wonder Woman and Jayna freeing the world's men (including the male super heroes) onto computer tape by the female villainess Medula.[83]

Mind uploading

editMind uploading is the (as of 2023[update]) speculative process of copying a human mind into a digital computer so it can be emulated there. This would require some form of advanced brain scan far more detailed than what is currently possible.

See also

editReferences

edit- ^ "What is digitization?". WhatIs.com. Retrieved 2023-04-14.

- ^ Collins Dictionary. (n.d.). Definition of 'digitize'. Retrieved December 15, 2021, from https://www.collinsdictionary.com/dictionary/english/digitize

- ^ a b c Mirzagayeva, Shamiya; Aslanov, Heydar (2022-12-15). "The digitalization process: what has it led to, and what can we expect in the future?" (PDF). Metafizika. 5 (4): 10–21. eISSN 2617-751X. ISSN 2616-6879. OCLC 1117709579. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2022-11-12. Retrieved 2022-10-14.

- ^ a b Bloomberg, Jason. "Digitization, Digitalization, And Digital Transformation: Confuse Them At Your Peril". Forbes. Retrieved 2023-04-14.

- ^ McQuail, D. (2000). McQuail's mass communication theory (4th edition). Sage.

- ^ a b c d e Brown, A. (2013). Practical digital preservation: A how-to guide for organizations of any size. Neal Schuman.

- ^ a b Daigle, Bradley J. (2012). "The Digital Transformation of Special Collections". Journal of Library Administration. 52 (3–4): 244–264. doi:10.1080/01930826.2012.684504. S2CID 56527894.

- ^ a b c LeFurgy, Bill (2011-07-15). "Digitization is Different than Digital Preservation: Help Prevent Digital Orphans! | The Signal". The Library of Congress. Retrieved 2023-04-14.

- ^ a b c d e Riley-Reid, Trevar D. (2015). "The hidden cost of digitization – things to consider". Collection Building. 34 (3): 89–93. doi:10.1108/CB-01-2015-0001.

- ^ a b "Collaboration between libraries, archives and museums (LAMS) in the digitisation of information in South Africa". scholar.google.com. Retrieved 2023-04-14.

- ^ "Moving pictures and sound - Digital Preservation Handbook". www.dpconline.org. Retrieved 2023-04-14.

- ^ a b c d e Hughes-Watkins, Lae'l (2018-05-16). "Moving Toward a Reparative Archive: A Roadmap for a Holistic Approach to Disrupting Homogenous Histories in Academic Repositories and Creating Inclusive Spaces for Marginalized Voices". Journal of Contemporary Archival Studies. 5 (1). ISSN 2380-8845.

- ^ a b Verheusen, A. (2008). Mass digitization by libraries: Issues concerning organisation, quality and efficiency. LIBER Quarterly, 18(1), 28-38.

- ^ a b Yoo, Dong Kyoon; Roh, James Jungbae (2019-03-04). "Adoption of e-Books: A Digital Textbook Perspective". Journal of Computer Information Systems. 59 (2): 136–145. doi:10.1080/08874417.2017.1318688. ISSN 0887-4417.

- ^ a b c "Session 7: Reformatting and Digitization". Northeast Document Conservation Center. Retrieved 2023-04-14.

- ^ Flew, Terry. 2008. New Media An Introduction. South Melbourne. 3rd Edition. South Melbourne: Oxford University Press.

- ^ "Digimation | 3D Training and Simulation". Retrieved 2023-04-14.

- ^ Hedstrom, Margaret (1997-05-01). "Digital Preservation: A Time Bomb for Digital Libraries" (PDF). Computers and the Humanities. 31 (3): 189–202. doi:10.1023/A:1000676723815. hdl:2027.42/42573. ISSN 1572-8412. S2CID 15327062.

- ^ a b c "What is the History of Digitization?". Kodak Digitizing. Retrieved 2023-04-14.

- ^ "Square Pixel Inventor Tries to Smooth Things Out". Wired. ISSN 1059-1028. Retrieved 2023-04-14.

- ^ a b "Page 1". nistdigitalarchives.contentdm.oclc.org. Retrieved 2024-11-22.

- ^ Kirsch, R. A. (1988). Earliest image processing. IEEE Annals of the History of Computing, 20(2). https://tsapps.nist.gov/publication/get_pdf.cfm?pub_id=821701

- ^ ICT Technologies. (2004, February 3). Analog vs. digital signals. Chapter 3: Module 2: Communication Systems. Archived from the original on March 3, 2008. Retrieved on December 15, 2021, from https://tsapps.nist.gov/publication/get_pdf.cfm?pub_id=821701

- ^ "How do we convert audio from analogue to digital and back?". BBC Science Focus Magazine. Retrieved 2023-04-14.

- ^ Lee, K.H.; Slattery, O.; Lu, R.; Tang, X.; McCrary, V. (2002). "The state of the art and practice in digital preservation". Journal of Research of the National Institute of Standards and Technology. 107 (1): 93–106. doi:10.6028/jres.107.010. PMC 4865277. PMID 27446721.

- ^ Waldfogel, Joel (2017). "How Digitization Has Created a Golden Age of Music, Movies, Books, and Television". Journal of Economic Perspectives. 31 (3): 195–214. doi:10.1257/jep.31.3.195.

- ^ "Good-bye, VHS; Hello, DVD". Computerworld New Zealand. Retrieved 2023-04-14.

- ^ Moses, Jeanette D. (2021-02-20). "How to digitize VHS tapes". Tom's Guide. Retrieved 2023-04-14.

- ^ "Super COOLSCAN 5000 ED | Nikon". www.nikonusa.com. Retrieved 2023-04-14.

- ^ "Swiss National Sound Archives". www.fonoteca.ch. Retrieved 2023-04-14.

- ^ a b c d e Breeding, Marshall (2014-11-01). "Ongoing Challenges in Digitization". Computers in Libraries. 34 (9): 16–18.

- ^ Champion, N. (2013, February/March). Delivering music digitisation projects: Issues and challenges. Crescendo, 92, 12-18.

- ^ Google. (2004, December 14). Google checks out library books [Press release]. http://googlepress.blogspot.com/2004/12/google-checks-out-library-books.html

- ^ "Libraries & Archivists Are Digitizing 480,000 Books Published in 20th Century That Are Secretly in the Public Domain | Open Culture". Retrieved 2023-04-14.

- ^ Tam, Marcella (2017). "Improving Access and "Unhiding" the Special Collections". The Serials Librarian. 73 (2): 179–185. doi:10.1080/0361526X.2017.1329178. S2CID 196043867.

- ^ "Microfilm". National Archives. 2016-08-15. Retrieved 2023-04-14.

- ^ CMCCONNELL (2013-08-16). "1. Microforms in Libraries and Archives". Association for Library Collections & Technical Services (ALCTS). Retrieved 2023-04-14.

- ^ Hughes, Lorna M. (2004). Digitizing Collections: Strategic Issues for the Information Manager. London: Facet Publishing. ISBN 1-85604-466-1. Chapter 1, "Why digitize? The costs and benefits of digitization", p. 3-30; here, especially p. 9-17.

- ^ "Guidelines on the Production and Preservation of Digital Audio Objects (web edition)". iasa-web.org.

- ^ Hughes (2004), p. 204.

- ^ Caplan, Priscilla (February–March 2008). "What is Digital Preservation?". Library Technology Reports. 44 (2): 7. Retrieved 2016-10-26.

- ^ Cloonan, M.V. and Sanett, S. "The Preservation of Digital Content," Libraries and the Academy. Vol. 5, No. 2 (2005): 213–37.

- ^ Newton, Isaac. "Philosophiæ Naturalis Principia Mathematica". Cambridge University Digital Library. Retrieved 10 January 2012.

- ^ Newton, Isaac. "Trinity College Notebook". Cambridge University Digital Library. Retrieved 10 January 2012.

- ^ Newton, Isaac. "College Notebook". Cambridge University Digital Library. Retrieved 10 January 2012.

- ^ Newton, Isaac. "Newton Papers". Cambridge University Digital Library. Retrieved 10 January 2012.

- ^ "al-Qurʼān". Cambridge University Digital Library. Retrieved 10 January 2012.

- ^ Google Books.

- ^ Baksik, C. "Fair Use or Exploitation? The Google Book Search Controversy," Libraries and the Academy. Vol. 6, No. 2 (2006): 399–415.

- ^ "Definition of Digitization - Gartner Information Technology Glossary". Gartner. Retrieved 2023-04-14.

- ^ Ross, S. (2000). Changing trains at Wigan: Digital Preservation and the future of scholarship (1st ed.). National Preservation Office (British Library). Retrieved December 15, 2021, from https://www.researchgate.net/publication/31869566_Changing_Trains_at_Wigan_Digital_Preservation_and_the_Future_of_Scholarship

- ^ "Fundamentals of AV Preservation - Chapter 4". Northeast Document Conservation Center. Retrieved 2023-04-14.

- ^ "SAA Dictionary: born digital". dictionary.archivists.org. Retrieved 2023-04-14.

- ^ Crestodina, Andy (2017-04-25). "What is the average website lifespan? 10 Factors In Website Life Expectancy". Orbit Media Studios. Retrieved 2023-04-14.

- ^ Library of Congress. (n.d.). Digital preservation. Retrieved December 15, 2021, from https://www.digitalpreservation.gov/

- ^ "Library of Congress. (2007). Technical Standards for Digital Conversion of Text and Graphic Materials" (PDF).

- ^ "Search Publications – Association of Research Libraries® – ARL®" (PDF). www.arl.org. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2012-05-05. Retrieved 2016-11-06.

- ^ Library of Congress, (2006). Preservation Digital Reformatting Program. https://www.loc.gov/preserv/prd/presdig/presintro.html

- ^ a b "ARSC Guide to Audio Preservation" (PDF).

- ^ Casey, Mike (January 2015). "Why Media Preservation Can't Wait: The Gathering Storm" (PDF). IASA Journal. 44: 14–22.

- ^ "ARSC Guide to Audio Preservation" (PDF). Retrieved 2019-05-04.

- ^ Institute, Canadian Conservation (2017-09-14). "The Digitization of Audio Tapes – Technical Bulletin 30". aem. Retrieved 2019-05-04.

- ^ a b Greene, M. A. (2010). MPLP: It's not just for processing anymore. The American Archivist, 73(1), 175-203.

- ^ a b c d Lampert, Cory (2018). "Ramping up". Digital Library Perspectives. 34 (1): 45–59. doi:10.1108/DLP-06-2017-0020.

- ^ UK Parliament. (2016, October 24). Parliamentary archives: The digitisation process [Video]. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=0p3-v0rp1rc

- ^ a b c d e f g Erway, R. (2008, December). Supply and demand: Special collections and digitisation. LIBER Quarterly, 18(3/4), 324-336.

- ^ Chapman, S. (2009, June 2). Chapter 2: Managing digitization. Library Technology Reports, 40(5), 13-21.

- ^ a b c d e f g Sutton, Shan C. (2012). "Balancing Boutique-Level Quality and Large-Scale Production: The Impact of "More Product, Less Process" on Digitization in Archives and Special Collections". RBM: A Journal of Rare Books, Manuscripts, and Cultural Heritage. 13 (1): 50–63. doi:10.5860/rbm.13.1.369.

- ^ a b Duran Casablancas, Cristina; Holtman, Marc; Strlič, Matija; Grau-Bové, Josep (2022-10-12). "The end of the reading room? Simulating the impact of digitisation on the physical access of archival collections". Journal of Simulation. 18 (2): 191–205. doi:10.1080/17477778.2022.2128911. ISSN 1747-7778. S2CID 252883425.

- ^ a b "6.6 Preservation and Selection for Digitization". Northeast Document Conservation Center. Retrieved 2023-04-14.

- ^ Anderson, Talea (2015). "Streaming the Archives: Repurposing Systems to Advance a Small Media Digitization and Dissemination Program". Journal of Electronic Resources Librarianship. 27 (4): 221–231. doi:10.1080/1941126X.2015.1092343. S2CID 61418169.

- ^ Skulan, Naomi (2018). "Staffing with students". Digital Library Perspectives. 34 (1): 32–44. doi:10.1108/DLP-07-2017-0024.

- ^ Kelly, E. (2014, May 14). Processing through digitization: University photographs at Loyola University New Orleans. Archival Practice, 1(1).

- ^ a b c d Manzuch, Z. (2017). Ethical issues in digitization of cultural heritage. Journal of Contemporary Archival Studies, 4(2), article 4. http://elischolar.library.yale.edu/jcas/vol4/iss2/4

- ^ a b c Shell-Weiss, Melanie; Benefiel, Annie; McKee, Kimberly (2017). "We Are All Teachers: A Collaborative Approach to Digital Collection Development". Collection Management. 42 (3–4): 317–337. doi:10.1080/01462679.2017.1344597. S2CID 196044884.

- ^ a b c Caswell, Michelle (2014). "Community-centered collecting: Finding out what communities want from community archives". Proceedings of the American Society for Information Science and Technology. 51: 1–9. doi:10.1002/meet.2014.14505101027. S2CID 52004250.

- ^ a b c d e f Verheusen, A. (2008). Mass digitization by libraries: Issues concerning organisation, quality and Efficiency. LIBER Quarterly, 18(1), 28-38.

- ^ Muktiarni, M; Widiaty, I; Abdullah, A G; Ana, A; Yulia, C (2019-12-01). "Digitalisation trend in education during industry 4.0". Journal of Physics: Conference Series. 1402 (7): 077070. Bibcode:2019JPhCS1402g7070M. doi:10.1088/1742-6596/1402/7/077070. ISSN 1742-6588.

- ^ a b c Duggineni, Sasidhar (2023-06-02). "Impact of Controls on Data Integrity and Information Systems". Science and Technology. 13 (2): 29–35.

- ^ Chapman, S. (2009, June 2). Chapter 2: managing digitization. Library Technology Reports, 40(5), 13-21.

- ^ a b Smithsonian Institution Archives. (n.d.). Digitizing collections. Retrieved October 10, 2021, from https://siarchives.si.edu/what-we-do/digital-curation/digitizing-collections

- ^ Society of American Archivists. (n.d.). External digitization standards. Retrieved October 23, 2021, from https://www2.archivists.org/standards/external/123

- ^ The Mind Maidens. Aired Nov. 5 1977 on the ABC Network along with other segments.

Further reading

edit- Anderson, Cokie G.; Maxwell, David C, Starting a Digitization Center, Chandos Publishing, 2004, ISBN 978-1843340737

- Bulow, Anna; Ahmon, Jess, Preparing Collections for Digitization, Facet Publishing, 2010, ISBN 978-1856047111

- Perrin, Joy, "Digitization of Flat Media: Principles and Practices", Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, 2015, ISBN 978-1442258099

- Piepenburg, Scott, "Digitizing Audiovisual and Nonprint Materials: the Innovative Librarian's Guide", Libraries Unlimited, 2015, ISBN 978-1440837807

- Robinson, Peter, Digitization of Primary Textual Sources, Office for Humanities Communication, 1993, ISBN 978-1897791059

- S Ross; I Anderson; C Duffy; M Economou; A Gow; P McKinney; R Sharp; The NINCH Working Group on Best Practices, Guide to Good Practice in the Digital Representation and Management of Cultural Heritage Materials, Washington DC: NINCH, 2002.

- Speranski, V. Challenges in AV Digitization and Digital Preservation

- 'The Library of Congress National Recording Preservation Plan'