Die Rabenschlacht (The Battle of Ravenna) is an anonymous 13th-century Middle High German poem about the hero Dietrich von Bern, the counterpart of the historical Ostrogothic king Theodoric the Great in Germanic heroic legend. It is part of the so-called "historical" Dietrich material and is closely related to, and always transmitted together with another Dietrich poem, Dietrichs Flucht. At one time, both poems were thought to have the same author, possibly a certain Heinrich der Vogler, but stylistic differences have led more recent scholarship to abandon this idea.[1]

Die Rabenschlacht concerns a failed attempt by the exiled Dietrich to reclaim his kingdom in Northern Italy from his treacherous uncle Ermenrich, with the help of an army provided by Etzel, king of the Huns. In the course of this attempt, Dietrich's younger brother and Etzel's young sons by his wife Helche are killed by Dietrich's former vassal Witege outside of Ravenna. Witege then flees into the sea and is rescued by a mermaid rather than fighting against Dietrich. The poem may be a dim reflection of the death of Attila's son Ellac at the Battle of Nedao in 454, combined with Theodoric the Great's siege of Ravenna in 491–493.[2] It would therefore be one of the oldest parts of the legends about Dietrich von Bern.

Summary

editDie Rabenschlacht begins a year after the end of Dietrichs Flucht, with Dietrich still in exile at the court of Etzel. Dietrich is still saddened by the loss of his men in the previous poem, especially Alphart. Etzel announces that he will give Dietrich a new army, and there is a large feast to celebrate Dietrich's marriage to Herrad, niece of his wife Helche. Helche, however, is troubled by a dream in which a wild dragon carries away her two sons and rips them to shreds. Meanwhile, a new army is assembled at Etzelburg. Helche and Etzel's sons Orte and Scharpfe beg Helche to be allowed to join the army. Etzel and Dietrich come in upon this conversation, and Etzel categorically refuses. Dietrich, however, promises to take good care of the young princes, so that Helche agrees and Orte and Scharpfe join the army.[3]

The army arrives in Italy, where it is greeted by Dietrich's loyal vassals who have remained there after the last campaign. Dietrich learns that Ermenrich has assembled a large army at Ravenna. The army heads to Bern (Verona), where Dietrich's young brother Diether has remained. Dietrich decides to leave Etzel's children with Diether in the care of the older warrior Elsan, and marches to Ravenna. The children, however, under the pretext of viewing the city, convince a reluctant Elsan to let them leave the city. They get lost and end up on the road to Ravenna, while Elsan looks for them in despair. Once the young warriors have spent a night outside the city, they reach the shore of the sea. In the dawn they encounter Witege. Diether tells Etzel's children that Witege is a warrior who betrayed Dietrich, and the three young warriors attack. Witege slays each of them in difficult combat; he is deeply distressed and laments Diether's death especially.[3]

Meanwhile, Dietrich fights a gruelling twelve-day battle outside Ravenna, defeating Ermenrich, who escapes. His treacherous advisor Sibeche, however, is captured by Eckehart, who ties him naked to a horse and leads him across the battlefield to avenge the death of the Harlungen at Sibeche's advice. As the dead are gathered to be buried, Elsan arrives with news that Etzel's sons are missing. The warrior Helpfrich then comes with news of their deaths. Dietrich finds their bodies on the seashore and breaks into despairing laments. He recognizes that the wounds on the young warriors bodies could only have been made by Witege's sword Mimming. Witege is then spotted; Dietrich jumps on his horse to attack, but Witege flees on his horse Schemming. Witege's uncle Rienolt, however, is also with him, and he turns to fight Dietrich and is slain. Dietrich pursues Witege to the edge of the sea and very nearly catches him, but Witege rides into the sea where he is rescued by the sea-spirit/mermaid (MHG merminne) Wâchilt who was his ancestress (identifiable more specifically as his great-grandmother in Swedish version of the Þiðreks saga). She tells him that Dietrich was so hot with anger that his armor was soft, and Witige could have easily defeated him. Now, however, the armor had hardened, and thirty Witiges could not defeat Dietrich. Dietrich meanwhile mourns on the shore. He goes back to Ravenna, where Ermenrich has fortified himself, and storms the city. Ermernich escapes, however, and Dietrich orders the city burned, as the inhabitants surrender. Rüdiger rides back to Hunland to bring Etzel the news of his sons deaths; however, Orte and Scharpfe's horses arrive at Etzelburg with bloody saddles. Helche is beside herself, but Rüdiger is able to calm her. Etzel sees that his sons deaths are not Dietrich's fault, and Dietrich returns to Etzel's court and back into Etzel and Helche's good graces.[4]

Dating, creation, and transmission

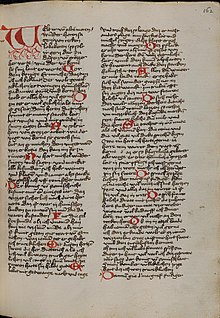

editDie Rabenschlacht is transmitted together with Dietrichs Flucht in four complete manuscripts and alone in one fragmentary manuscript:[5]

- Riedegger Manuscript (R), Staatsbibliothek Berlin, Ms. germ 2o 1062, on parchment from the end of the thirteenth century, from Niederösterreich. Contains various literary texts.[6]

- Windhager Manuscript (W), Österreichische Nationalbibliothek Vienna, Cod. 2779, parchment, first quarter of the fourteenth century, from Niederösterreich. Contains various literary texts and the Kaiserchronik.[6]

- (P) Universitätsbibliothek Heidelberg, Cpg 314, paper, 1443/47, from Augsburg. Contains various literary texts.[6]

- Ambraser Heldenbuch (A), Österreichische Nationalbibliothek Vienna, Cod. Series Nova 2663, parchment, 1504/1515, from Tyrol. Various literary texts.[7]

- Universitätsbibliothek Graz, Ms. 1969 (S), parchment, mid fourteenth-century, in Austro-Bavarian dialect. Contains a fragment of Die Rabenschlacht.[8]

The origins of the earliest manuscripts as well as the dialect of the poem indicate that it was composed in Austria, sometime before 1300.[9] Most modern scholarship holds Die Rabenschlacht to have been composed earlier than Dietrichs Flucht: Joachim Heinzle notes that Die Rabenschlacht contains allusions to Wolfram von Eschenbach's Willehlam (c. 1220) and cannot have been composed any earlier than that.[9] Werner Hoffmann suggests that Die Rabenschlacht may have been composed around 1270, before being reworked and placed together with Dietrichs Flucht in the 1280s.[10] Victor Millet questions whether Die Rabenschlacht is really an earlier work than Dietrichs Flucht,[11] and Elisabeth Lienert suggests that the poems were actually composed at roughly the same time, though older versions of Die Rabenschlacht must have existed.[12]

As with almost all German heroic epic, Die Rabenschlacht is anonymous.[13] Early scholarship believed that both Dietrichs Fluch and Die Rabenschlacht had a single author, Heinrich der Vogler; however, the formal and stylistic differences between the two epics have caused this theory to be abandoned.[14] The manuscript transmission nevertheless makes clear that Die Rabenschlacht and Dietrichs Flucht were viewed as a single work by contemporaries.[11] Someone, perhaps Heinrich der Vogler, has also reworked both texts to an extent so that their contents do not contradict each other.[15]

Metrical form

editDie Rabenschlacht consists of 1140 unique stanzas, in a form that is not found in any other poem.[16] Like other stanzaic heroic poems, it was probably meant to be sung,[17] but no melody survives.[18][16] Heinzle analyzes the stanza as consisting of three "Langzeilen" with rhymes at the caesuras: a||b, a||b, c||c. The first line consists of three metrical feet before the caesura, then three additional feet; the second of three feet before the caesura, then four additional feet; and the third of three feet before the caesura, and five or even six additional feet.[19] Heinzle prints the following example as typical:

- Welt ir in alten maeren a || wunder hoeren sagen, b

- von recken lobebaeren, a || sô sult ir gerne dar zuo dagen. b

- von grôzer herverte, c || wie der von Bern sît sîniu lant erwerte c

In some stanzas, the rhymes at the caesura in lines 1 and 2 are absent, giving a scheme: x|b, x|b, c|c.[20] It is also possible to interpret the stanza as consisting of six shorter lines, with rhyme scheme ABABCC.[16] Consequently, the same stanza as above is printed in the edition by Elisabeth Lienert and Dorit Wolter as:

- Welt ir in alten mæren a

- wnder horen sagen b

- von rekchen lobewæren, a

- so sult ir gerne dar zů dagen. b

- Von grozer herverte, c

- wie der von Bern sit siniu lant erwerte c

Genre and themes

editDie Rabenschlacht has been described as "elegiac" and "sentimental," particularly in relation to Dietrichs Flucht.[21] Stylistically, the poem is notable for its hyperbole in its depictions of violence—the battle at Ravenna takes twelve days and the warriors literally wade in blood among mountains of corpses—and emotions, particularly of grief.[22][23] The numbers of warriors involved are similarly exaggerated, with Ermenrich's army including 1,100,00 (eilf hundert tūsent) warriors or more.[23] Neither Werner Hoffmann nor Victor Millet see the poem as particularly heroic, with Millet nevertheless noting that the poem does not criticize the use of violence.[24][25]

The poem makes numerous allusions to the Nibelungenlied, beginning with the opening stanza, which cites the opening stanza of the C version of the Nibelungenlied.[26] Edward Haymes and Susan Samples suggest that the poem exists as a kind of prequel to the Nibelungenlied.[27] In the course of the poem, characters from the Nibelungenlied fight on the side of Ermenrich, including Siegfried, Gunther and Volker, as well as their enemies from the Nibelungenlied, Liudegast and Liudeger. Siegfried is defeated by Dietrich and forced to plea for his life, confirming Dietrich's superiority.[28] Michael Curschmann holds the encounters between Dietrich and Siegfried here and in the Rosengarten zu Worms to have their origins in an oral tradition.[29] However, Elisabeth Lienert sees the battles in Die Rabenschlacht as part of a literary rivalry between the two traditions, an intertextual relationship.[30] The poem includes allusions to other thirteenth-century literary texts as well,[31] including Wolfram von Eschenbach's Willehalm. [9] This confirms its nature as a literary text, in dialogue with other literature.[31]

Relation to oral tradition

editThe general outline of the story told in Die Rabenschlacht, about the death of Etzel and Herche's sons, is often considered to be one of the oldest components of the legend of Theodoric. It is first alluded to in the Nibelungenklage, a poem likely written shortly after the Nibelungenlied (c. 1200).[32] Older scholarship proposed a Gothic song as the earliest version.[33] According to this theory, the song was inspired by the Battle of Nedao (454), a rebellion of Germanic tribes after the death of Attila the Hun, in which Attila's favorite son and successor Ellac died.[34] Theodoric the Great's father Theodemar is thought to have fought on the side of the Huns in this battle, with his actions transferred to his more famous son in the oral tradition.[34][35] Elisabeth Lienert suggests the poem's location at Ravenna may have been influenced by the historical Theodoric the Great besieging his enemy Odoacer there from 491 to 493.[2] Witige's character is sometimes thought to have been influenced by Witigis, a Gothic king and usurper who surrendered Ravenna to the Byzantine army.[36] Diether is similarly thought to have a connection to the historical Theodahad, whom Witigis betrayed, usurping the Ostrogothic throne.[37] Werner Hoffmann suggests that Ermenrich's rather small role in Die Rabenschlacht is because the original tale of Witige killing Etzel's sons and Diether has been only roughly inserted into the larger framework of Dietrich's exile.[38] Joachim Heinzle largely dismisses such attempts at deducing the roots of the poem as unfruitful.[39]

An alternative version of the events of the Rabenschlacht is found in the Old Norse Thidrekssaga. There we are told that King Ermanrik was misled into attacking his nephew Didrik because of his counsellor Sifka (Sibeche in Middle High German), who was avenging Ermanrik's rape of his wife by leading him to his doom. Didrik goes into exile at Attila's court and makes an attempt to return to his kingdom with a Hunnish army, bringing along his brother Thether (Diether) and Attila's two sons Erp and Ortwin. The army fights a mighty battle against Ermanrik at Gronsport on the Mosel and defeats him. During the battle, Wiðga (Witege) kills Thether, Erp, and Ortwin; Didrik pursues Wiðga, breathing fire, until the latter disappears in the (non-existent) mouth of the Mosel into the sea. Didrik throws his spear after Wiðga, and one can still see it today. Didrik then returns to exile. Joachim Heinzle notes that it is unclear how much of the variation between the version found in Die Rabenschlacht and that found in the Thidrekssaga is the work of the latter's compiler or comes from alternative versions in oral circulation. [40] The late medieval Heldenbuch-Prosa corroborates the Thidrekssaga's version of the story of why Sibeche betrayed Ermenrich, and it is clear that the composer of the Heldenbuch-Prosa did not have access to the Thidrekssaga.[41] This indicates that at least some of the Thidrekssaga's changes may come from oral tradition, indicating the existence of multiple versions of the story.[42] The scholar Norbert Voorwinden has suggested that the author of Die Rabenschlacht was largely unaware of the oral tradition, creating an entirely new work on the basis of an allusion to the death of Etzel's sons in the Nibelungenklage.[43]

Attempts have been made to connect the catalogues of warriors found in the work with signs of oral formulaic composition.[44]

References

edit- ^ Heinzle 1999, pp. 58–60.

- ^ a b Lienert 2015, p. 99.

- ^ a b Heinzle 1999, p. 70.

- ^ Heinzle 1999, pp. 70–71.

- ^ Heinzle 1999, p. 58.

- ^ a b c Heinzle 1999, p. 59.

- ^ Heinzle 1999, pp. 59–60.

- ^ Heinzle 1999, p. 60.

- ^ a b c Heinzle 1999, p. 72.

- ^ Hoffmann 1974, p. 162.

- ^ a b Millet 2008, p. 401.

- ^ Lienert 2015, pp. 101–102.

- ^ Hoffmann 1974, pp. 11–12.

- ^ Hoffmann 1974, pp. 161–162.

- ^ Lienert 2015, p. 102.

- ^ a b c Millet 2008, p. 405.

- ^ Heinzle 1999, p. 64.

- ^ Heinzle 1999, pp. 66–67.

- ^ Heinzle 1999, pp. 65–66.

- ^ Heinzle 1999, pp. 66.

- ^ Kuhn 1980, p. 118.

- ^ Heinzle 1999, p. 81.

- ^ a b Hoffmann 1974, pp. 166–167.

- ^ Hoffmann 1974, p. 167.

- ^ Millet 2008, p. 408.

- ^ Heinzle 1999, p. 65.

- ^ Haymes & Samples 1996, p. 80.

- ^ Lienert 1999, pp. 24–25.

- ^ Curschmann 1989, pp. 399–400.

- ^ Lienert 1999, pp. 26–34.

- ^ a b Millet 2008, p. 406.

- ^ Heinzle 1999, pp. 25–26.

- ^ Rosenfeld 1955, pp. 212–233.

- ^ a b Hoffmann 1974, p. 163.

- ^ Gillespie 1973, pp. 25, 43.

- ^ Gillespie 1973, p. 147.

- ^ Gillespie 1973, p. 24.

- ^ Hoffmann 1974, p. 168.

- ^ Heinzle 1999, p. 76.

- ^ Heinzle 1999, p. 78.

- ^ Heinzle 1999, pp. 78–80.

- ^ Heinzle 1999, pp. 78–79.

- ^ Voorwinden 2007, pp. 243–259.

- ^ Homann 1977, pp. 415–435.

Editions

edit- Martin, Ernest, ed. (1866). "Die Rabenschlacht". Deutsches Heldenbuch. Vol. 2. Berlin: Weidmann. pp. 219–326. Retrieved 3 April 2018.

- Lienert, Elisabeth; Wolter, Dorit, eds. (2005). Rabenschlacht: textgeschichtliche Ausgabe. Tübingen: Niemeyer. ISBN 3484645024.

- Klarer, Mario, ed. (2021). Rabenschlacht. Walter de Gruyter GmbH & Co KG. ISBN 3110719118.

Bibliography

edit- Bertelsen, Henrik, ed. (1905–1911). Þiðriks saga af Bern. Samfund til udgivelse af gammel nordisk litteratur, 34. Vol. 1. Copenhagen: Møller. Archived from the original on 2011-12-08.

- Curschmann, Michael (1989). "Zur Wechselwirkung von Literatur und Sage: Das 'Buch von Kriemhild' und 'Das Buch von Bern'". Beiträge zur Geschichte der deutschen Sprache und Literatur. 111: 380–410.

- Gillespie, George T. (1973). Catalogue of Persons Named in German Heroic Literature, 700–1600: Including Named Animals and Objects and Ethnic Names. Oxford: Oxford University. ISBN 9780198157182.

- Handschriftencensus (2001b). "Gesamtverzeichnis Autoren/Werke: 'Rabenschlacht". Handschriftencensus. Retrieved 31 March 2018.

- Haymes, Edward R.; Samples, Susan T. (1996). Heroic legends of the North: an introduction to the Nibelung and Dietrich cycles. New York: Garland. pp. 79–80. ISBN 0815300336.

- Haymes, Edward R., tr. (1988). The Saga of Thidrek of Bern. Garland. ISBN 0-8240-8489-6.

- Heinzle, Joachim (1999). Einführung in die mittelhochdeutsche Dietrichepik. Berlin, New York: De Gruyter. pp. 58–83. ISBN 3-11-015094-8.

- Hoffmann, Werner (1974). Mittelhochdeutsche Heldendichtung. Berlin: Erich Schmidt. pp. 161–171. ISBN 3-503-00772-5.

- Homann, Holger (1977). "Die Heldenkataloge in der historischen Dietrichepik und die Theorie der mündlichen Dichtung". Modern Language Notes. 92: 415–435.

- Kuhn H (1980). "Dietrichs Flucht und Rabenschlacht". In Ruh K, Keil G, Schröder W (eds.). Die deutsche Literatur des Mittelalters. Verfasserlexikon. Vol. 2. Berlin, New York: Walter De Gruyter. cols 116–127. ISBN 978-3-11-022248-7.

- Lienert, Elisabeth (1999). "Dietrich contra Nibelungen: Zur Intertextualität der historischen Dietrichepik". Beiträge zur Geschichte der deutschen Sprache und Literatur. 121: 23–46. doi:10.1515/bgsl.1999.121.1.23. S2CID 162203009.

- Lienert, Elisabeth (2015). Mittelhochdeutsche Heldenepik. Berlin: Erich Schmidt. pp. 101–110. ISBN 978-3-503-15573-6.

- Millet, Victor (2008). Germanische Heldendichtung im Mittelalter. Berlin, New York: de Gruyter. pp. 400–409. ISBN 978-3-11-020102-4.

- Rosenfeld, Hellmut (1955). "Wielandlied, Lied von Frau Helchen Söhnen und Hunnenschlachtlied: Historische Wirklichkeit und Heldenlied". Beiträge zur Geschichte der deutschen Sprache und Literatur (Tübingen). 77: 212–248.

- Voorwinden, Norbert (2007). "Dietrich von Bern: Germanic Hero or Medieval King? On the Sources of Dietrichs Flucht and Rabenschlacht". Neophilologus. 91 (2): 243–259. doi:10.1007/s11061-006-9010-3. S2CID 153590793.

External links

editFacsimiles

edit- Ambraser Heldenbuch (A), Vienna. (Dietrichs Flucht starts at image 167)

- Universitätsbibliothek Heidelberg, Cpg 314 (P)

- Riedegger Manuscript (R), Berlin

- Universitätsbibliothek Graz, Ms. 1969 (S)

- Windhager Manuscript (W), Vienna. (Dietrichs Flucht starts at image 237)