Richard Howard Stafford Crossman OBE (15 December 1907 – 5 April 1974) was a British Labour Party politician. A university classics lecturer by profession, he was elected a Member of Parliament in 1945 and became a significant figure among the party's advocates of Zionism. He was a Bevanite on the left of the party, and a long-serving member of Labour's National Executive Committee (NEC) from 1952.

Richard Crossman | |

|---|---|

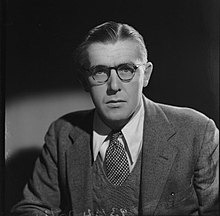

Crossman in 1947 | |

| Secretary of State for Social Services | |

| In office 1 November 1968 – 19 June 1970 | |

| Prime Minister | Harold Wilson |

| Preceded by | Position established |

| Succeeded by | Keith Joseph |

| Lord President of the Council Leader of the House of Commons | |

| In office 11 August 1966 – 18 October 1968 | |

| Prime Minister | Harold Wilson |

| Preceded by | Herbert Bowden |

| Succeeded by | Fred Peart |

| Minister of Housing and Local Government | |

| In office 16 October 1964 – 11 August 1966 | |

| Prime Minister | Harold Wilson |

| Preceded by | Keith Joseph |

| Succeeded by | Tony Greenwood |

| Shadow Secretary of State for Education | |

| In office 14 February 1963 – 16 October 1964 | |

| Leader | Harold Wilson |

| Succeeded by | Quintin Hogg |

| Chair of the National Executive Committee of the Labour Party | |

| In office 7 October 1960 – 6 October 1961 | |

| Leader | Hugh Gaitskell |

| Preceded by | George Brinham |

| Succeeded by | Harold Wilson |

| Member of Parliament for Coventry East | |

| In office 5 July 1945 – 8 February 1974 | |

| Preceded by | Constituency created |

| Succeeded by | Constituency abolished |

| Personal details | |

| Born | Richard Howard Stafford Crossman 15 December 1907 London, England |

| Died | 5 April 1974 (aged 66) Banbury, England |

| Political party | Labour |

| Spouses |

|

| Alma mater | New College, Oxford |

Crossman was a Cabinet minister in Harold Wilson's governments of 1964–1970, first for Housing, then as Leader of the House of Commons, and then for Social Services. In the early 1970s, Crossman was editor of the New Statesman. He is remembered for his highly revealing three-volume Diaries of a Cabinet Minister, published posthumously.

Early life

editCrossman was born on 15 December 1907 at Buckhurst Hill House, Essex,[1] the son of Charles Stafford Crossman,[2] a barrister and later a High Court judge, and Helen Elizabeth (née Howard). Helen was of the Howard family of Ilford descended from Luke Howard, a Quaker chemist and meteorologist who founded the pharmaceutical company Howards and Sons.[3]

Crossman grew up in Buckhurst Hill, Essex, and was educated at Twyford School, and at Winchester College (although founders' kin privileges at Winchester were abolished in 1857,[4] Crossman was "founder's kin", being descended from William of Wykeham through John Danvers, one of his father's ancestors),[5][6] where he became head boy. He excelled academically and on the football field. He studied Classics at New College, Oxford, where he was friendly with W.H. Auden.[7] He received a double first and became a fellow in 1931. He taught philosophy at the university before becoming a Workers' Educational Association lecturer. He was a councillor on Oxford City Council, and became head of its Labour group in 1935.[8]

Personal life

editCrossman, who had been noted for his good looks as a youth, had predominantly same-sex affairs at Oxford.[9] In an early diary, he describes an Easter holiday with an unnamed young poet: "He kept me in a little white-washed room for a fortnight because his mouth was against mine and we were completely together."[10]

After being married to Erika Glück, a divorcée, whom he met while travelling in Germany after graduation, he married Zita Baker (ex-wife of John Baker) in 1937.[11]

Service in World War II and afterwards

editAt the outbreak of the Second World War, Crossman joined the Political Warfare Executive under Robert Bruce Lockhart, where he headed the German Section.[12] He produced anti-Nazi propaganda broadcasts for the BBC German Service and the Radio of the European Revolution, set up by the Special Operations Executive (SOE). He eventually became Assistant Chief of the Psychological Warfare Division of SHAEF and was awarded an OBE for his wartime service.[13]

In April 1945, Crossman was one of the first [citation needed] British officers to enter the former Dachau concentration camp. With war correspondent Colin Wills, Crossman co-wrote the script for German Concentration Camps Factual Survey, a British government documentary, produced by Sidney Bernstein with treatment advice by Alfred Hitchcock, that showed gruelling scenes from Nazi concentration camps. The uncompleted film was shelved for decades before being assembled by scholars at the Imperial War Museum and released in 2014. That same year, German Concentration Camps Factual Survey was itself the subject of a documentary, Night Will Fall.[14][15]

Crossman became a key participant in the annual Königswinter Conference, organised by Lilo Milchsack to bring together British and German legislators, academics and opinion-formers from 1950 onwards. The conferences were credited with helping to heal bad memories created by the war. At them, Crossman met the German politician Hans von Herwarth, the ex-soldier Fridolin von Senger und Etterlin, future German President Richard von Weizsäcker and other leading German decision makers. Other attendees at the conferences included Denis Healey, soon to become a Labour Party politician, and Robin Day, later a political broadcaster.[16]

Political career: 1945–51

editCrossman entered the House of Commons at the 1945 general election as the Member of Parliament (MP) for Coventry East, a seat he held until shortly before he died in 1974. During 1945–46 he served, on the nomination of the Foreign Secretary Ernest Bevin, as a member of the Anglo-American Committee of Inquiry into the Problems of European Jewry and Palestine. The committee's report, submitted in April 1946, included a recommendation for 100,000 Jewish displaced persons to be permitted to enter Mandatory Palestine. Short of American financial and military assistance, the British government refused to implement the report's recommendations. Thereafter Crossman led the socialist opposition to the official British policy for Palestine. That incurred Bevin's enmity, and may have been the primary factor which prevented Crossman from achieving ministerial rank during the 1945–51 government. Crossman initially supported the Arab cause, but became a lifelong Zionist after meeting Chaim Weizmann. In his diary, he described Weizmann as "one of the very few great men I have ever met."[17] Crossman remained a supporter of Israel during his political career from the late-1940s until his death in 1974.[18] At a 1959 lecture in Israel, Crossman attacked what he perceived as hypocrisy over Israel regarding anti-indigenous racism.[19]

"For generations it had been assumed that civilisation would be spread by the white man settling overseas... No one, until the 20th century, seriously challenged their right, or indeed their duty, to civilise these continents by physically occupying them, even at the cost of wiping out the aboriginal population."[20]

During the Palestine Emergency, Crossman's support for Zionism went as far as collaborating against the British Mandate government. One such attack in which he was implicated was the Night of the Bridges. Although no British soldiers were killed in the initial attacks, 20-year-old Royal Engineer Roy Charles Allen was killed while trying to defuse an undetonated bomb.[21] Christopher Mayhew later recounted the collaboration in his book Publish It Not: The Middle East Cover-up:

"One day, Crossman, now in the House of Commons, came to see Strachey… [Crossman] had heard from his friends in the Jewish Agency that they were contemplating an act of sabotage … Should this be done, or should it not? Few would be killed … Crossman asked Strachey for his advice … The next day in the smoking room at the House of Commons, Strachey gave his approval to Crossman. The Haganah went ahead and blew up all the bridges over the [River] Jordan."[19]

Crossman never forgave Bevin or Clement Attlee for their involvement in the war in Palestine and for trying to stop the establishment of Israel:

"You seem to have forgotten that Clement Attlee and Ernest Bevin plotted to destroy the Jews in Palestine and the encouraged the Arabs to murder the lot. I fought them at the time as murderers. I can never trust them again and you can't expect me to forgive them for genocide."[22]

Crossman cemented his role as a leader of the left-wing of the Parliamentary Labour Party in 1947 by co-authoring the Keep Left pamphlet, and later became one of the more prominent Bevanites.

Anti-communist propaganda

editCrossman is considered by historians to be a central figure to British Cold War propaganda due to his collaboration with the Information Research Department (IRD), a secret branch of the UK Foreign Office dedicated to disinformation, anti-communist, and pro-colonial propaganda during the Cold War.[23] The IRD secretly funded, published and distributed many of Crossman's articles and books,[24] including The God that Failed.[25][26] His anti-communist works were not only of special interest to British propagandists but were also secretly sponsored by the US government, which translated his works into Malay and Chinese.[27] Crossman was also a regular contributor to Encounter, an "anti-Stalinist" publication which received funding from MI6 and the CIA.[28]

Crossman's intense relationship with disinformation for propaganda purposes led to many people nicknaming him "Dick Double-Crossman".[29] His name was also included within one of George Orwell's notebooks following the discovery of Orwell's list, being noted by Orwell as being "Too dishonest to be outright F. T" (fellow-traveller).[30]

Political career: 1951–70

editCrossman was a member of the National Executive Committee of the Labour Party from 1952 to 1967 and served as its chair from 1960 to 1961.

In 1957, Crossman was one of the plaintiffs, along with Aneurin Bevan and Morgan Phillips, in a claim for libel made against The Spectator, which had described the three men as drinking heavily during a socialist conference in Italy.[31] Having sworn that the charges were untrue, the three collected damages from the magazine. Many years later, Crossman's posthumously published diaries confirmed that The Spectator's charges had been true and that all three of them had perjured themselves.[32]

Crossman was Labour's spokesman on education before the 1964 general election, but upon forming the new Government Harold Wilson appointed him to the Cabinet as Minister of Housing and Local Government. In 1966, Crossman became Lord President of the Council and Leader of the House of Commons.

Between 1968 and 1970, he was the first Secretary of State for Social Services, in which position he worked on an ambitious proposal to supplement Britain's flat-rate state pension with an earnings-related element. The proposal had not, however, been passed into law at the time the Labour Party lost the 1970 general election. During the months of political turmoil that led up to the election loss, Crossman had been considered, however briefly, as a last-minute option to replace Wilson as Prime Minister.[citation needed]

Books and journalism

editAfter Labour's general election defeat in 1970, Crossman resigned from the Labour front bench to become editor of the New Statesman, where he had been a frequent contributor and assistant editor from 1938 until 1955. He left the New Statesman in 1972.

In the 1950s and 1960s, Crossman also had a regular column titled "Crossman Says..." in the Daily Mirror, the Labour-supporting tabloid newspaper. Along with the column of "Cassandra", Crossman's reporting provided the bulk of political and international commentary in the newspaper.

Crossman was a prolific writer and editor. In Plato To-Day (1937) he imagines Plato visiting Nazi Germany and Stalinist Russia. Plato criticises Nazi and Communist politicians for misusing the ideas he had set forth in the Republic.[33] After the war, Crossman edited The God That Failed (1949), a collection of anti-Communist essays by former Communists.

Crossman is best remembered for his colourful and highly subjective three-volume Diaries of a Cabinet Minister, written while he was living in Vincent Square, published posthumously from 1975 to 1977 and covering his time in government from 1964 to 1970. The diaries appeared after he had died, and following a legal battle by the government to block publication. One of Crossman's legal executors was Michael Foot, then a cabinet minister, who opposed his own government's attempts to suppress the diaries.[34] Among other things, the diaries describe Crossman's battles with "the Dame", his Permanent Secretary Evelyn Sharp, GBE (1903–1985), the first woman in Britain to hold the position. Crossman's backbench diaries were published in 1981. Crossman's diaries were an acknowledged source for the television comedy series Yes Minister.[35][36]

Death

editCrossman died of liver cancer on 5 April 1974 at his home in Oxfordshire. He was survived by his third wife, Anne Patricia (15 April 1920 – 3 October 2008; née McDougall, daughter of Patrick McDougall, of Prescote Manor, Cropredy, founder of the Banbury cattle market), with whom he shared common descent from the Danvers family of Cropredy. Anne Crossman worked at Bletchley Park during the Second World War, and served as secretary to Maurice Edelman MP. The Crossmans had two children, Patrick and Virginia.[6]

Legacy

editThe Richard Crossman Building, built in 1971, at Coventry University is named in his honour.[37] Crosssman's papers are at the Modern Records Centre, at the University of Warwick.[38]

Richard Crossman features in the theatre production Little Edens, set during the Florence Park rent strike of 1934.

The former Labour MP Bryan Magee wrote in his autobiography Making the Most of It that Crossman was "the most brilliant debater I have heard".[39]

Published works

edit- Government and the Governed (A History of Political Ideas and Political Practice) London: Cristophers (1939)

- Plato To-Day New York: Oxford University Press (1937)

- Palestine Mission: A Personal Record New York: Harper (1947)

- The God That Failed New York: Harper (1949) (editor)

- The Charm of Politics, and other Essays in Political Criticism Hamish Hamilton (1958)

- A Nation Reborn: The Israel of Weizmann, Bevin and Ben-Gurion New York: Atheneum (1960)

- The Politics of Socialism New York: Atheneum (1965)

- The Myths of Cabinet Government Cambridge: Harvard University Press (1972)

- Diaries of a Cabinet Minister (three volumes, 1975, 1976 and 1977)

- The Crossman Diaries: Selections from the Diaries of a Cabinet Minister, 1964–1970 (1979) abridged edition, edited by Anthony Howard

- The Backbench Diaries of Richard Crossman (1981)

Biographies

edit- Anthony Howard (1990), Crossman: The Pursuit of Power, Jonathan Cape

- Tam Dalyell (1989), Dick Crossman: A Portrait

- Victoria Honeyman (2006), Richard Crossman; A Reforming Radical of the Labour Party, I.B. Tauris ISBN 978-1845115531

References

edit- ^ RHS Crossman, birth certificate, issued 30 Dec 1907

- ^ Biographical Register 1880–1974 - Corpus Christi College (University of Oxford) - Google Books. The College. 3 January 2007. ISBN 9780951284407. Retrieved 30 September 2018.

- ^ Brief Lives with some memoirs, Alan Watkins, Elliot and Thompson, 2004, pp. 54–55.

- ^ "The Reverend Anthony Trotman". The Daily Telegraph. 4 November 2006. Retrieved 30 September 2018.

- ^ Brief Lives with some memoirs, Alan Watkins, Elliot and Thompson, 2004, pg 54

- ^ a b "Anne Crossman". The Daily Telegraph. 8 October 2008. Retrieved 30 September 2018.

- ^ Bloch, Michael (2015). Closet Queens. Little, Brown. p. 229. ISBN 978-1408704127.

- ^ "Modern Records Centre, University of Warwick". Richard Crossman. 16 June 1945. Retrieved 16 July 2024.

- ^ Michael Bloch. "Double lives – a history of sex and secrecy at Westminster". The Guardian. Retrieved 30 September 2018.

- ^ Howard, Anthony (1990). Crossman: The Pursuit of Power. Cape. p. 24. ISBN 9780712651158.

- ^ "About Richard Crossman - a short biography".

- ^ Mayne, Richard (1 April 2003). In Victory, Magnanimity, in Peace, Goodwill. Psychology Press. p. 6. ISBN 0-7146-5433-7.

- ^ "No. 37308". The London Gazette (Supplement). 12 October 1945. p. 5067.

- ^ Jeffries, Stuart (9 January 2015). "The Holocaust film that was too shocking to show". The Guardian. Retrieved 11 January 2015.

- ^ "German Concentration Camps Factual Survey". Imperial War Museum. Retrieved 31 January 2015.

- ^ Nigel Nicolson, "Long Life: Presiding Genius", The Spectator, 15 August 1992. Retrieved 28 November 2015.

- ^ Cohen, Michael J. (14 July 2014). Palestine and the Great Powers, 1945–1948. Princeton University Press. ISBN 9781400853571 – via Google Books.

- ^ "Crossman and the creation of Israel - Modern Records Centre, University of Warwick". warwick.ac.uk.

- ^ a b Winstanley, Asa (25 July 2017). "When Israel's friends in Labour advocated genocide". The Electronic Intifada. Retrieved 11 June 2024.

- ^ Not Available (1960). Encounter Vol.15, No. 1-6(july-dec)1960.

- ^ "Roll of Honour - Databases - Palestine 1945-1948 - British Casualties - Search Results". www.roll-of-honour.com. Retrieved 24 June 2024.

- ^ Fry, G. (7 December 2004). The Politics of Decline: An Interpretation of British Politics from the 1940s to the 1970s. Springer. p. 81. ISBN 978-0-230-55445-0.

- ^ Rubin, Andrew N. (2012). Archives of Authority: Empire, Culture and the Cold War. Woodstock: Princeton University Press. p. 37.

- ^ Defty, Andrew (2005). Britain, America and Anti-Communist Propaganda 1945-1953: The Information Research Department. E-book version: Routledge. p. 87.

- ^ Jenks, John (2006). British Propaganda and News Media in the Cold War. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press. p. 71.

- ^ Mitter, Rana (2005). Across the Block: Cold War Cultural and Social History. Taylor & Francis e-library: Frank Cass and Company Limited. p. 115.

- ^ Defty, Andrew (2005). Britain, America and Anti-Communist Propaganda 1945–1953: The Information Research Department. E-book version: Routledge. p. 160.

- ^ Wilford, Hugh (2013). The CIA, the British Left and the Cold War: Calling the Tune?. Abingdon: Routledge. p. 286.

- ^ Cull, Nicholas J.; Culbert, David; Welch, David (2003). Propaganda and Mass Persuasion: A Historical Encyclopaedia, 1500 to Present. Oxford: ABC-CLIO. p. 100.

- ^ Lashmar, Paul; Oliver, James (1988). Britain's Secret Propaganda War 1948–1977. Phoenix Mill: Sutton Publishing. p. 97.

- ^ "Messrs Bevan, Morgan Phillips and Richard Crossman... puzzled the Italians by their capacity to fill themselves like tanks with whisky and coffee... Although the Italians were never sure the British delegation were sober, they always attributed to them an immense political acumen." See Bose, Mihir, "Britain's Libel Laws: Malice Aforethought", History Today, 5 May 2013.

- ^ Roy Jenkins wrote of his former colleagues (in "Aneurin Bevan" in Portraits and Miniatures, 2011) that they "sailed to victory on the unfortunate combination of Lord Chief Justice Goddard's prejudice against the anti-hanging and generally libertarian Spectator of those days and the perjury of the plaintiffs, subsequently exposed in Crossman's endlessly revealing diaries." Geoffrey Wheatcroft wrote (in The Guardian, 18 March 2000, "Lies and Libel"): "Fifteen years later, Crossman boasted (in my presence) that they had indeed all been toping heavily, and that at least one of them had been blind drunk." Dominic Lawson wrote (in The Independent, "Chris Huhne's downfall is another example of the amazing risks a politician will take". 4 February 2013): "Crossman's posthumously published diaries revealed that the story was accurate; and in 1978 Brian Inglis on What the Papers Say revealed that Crossman had told him a few days after the case that they had committed perjury". Mihir Bose (in "Britain's Libel Laws: Malice Aforethought", History Today, 5 May 2013) quotes Bevan's biographer, John Campbell, to the effect that the case had destroyed the career of the young journalist involved, Jenny Nicholson.

- ^ Goldhill, Simon, Love, Sex and Tragedy, U. Chicago Press, 2004, p. 202

- ^ Anthony Howard, "Michael Foot: The last of a dying breed", The Telegraph, 5 March 2010.

- ^ "Yes Minister Questions & Answers". Jonathan Lynn Official Website. Archived from the original on 19 November 2014. Retrieved 6 September 2007.

- ^ Crossman, Richard (1979). Diaries of a Cabinet Minister: Selections, 1964–70. London: Hamish Hamilton Ltd. ISBN 0-241-10142-5.

- ^ "Buildings". Coventry University. Retrieved 6 November 2019.

- ^ "Papers of Richard Crossman MP (1907-1974), Labour politician, and associated people". Modern Records Centre. Retrieved 2 October 2023.

- ^ Magee, Bryan (2018). Making the Most of It. Studio 28. p. 307. ISBN 9781980636137.

External links

edit- Dalyell, Tam (13 December 2002). "Tam Dalyell on Richard Crossman". Great Lives. BBC Radio 4. Retrieved 30 August 2009.

- Howard, Anthony (January 2008). "Crossman, Richard Howard Stafford (1907–1974)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/30987. Retrieved 30 August 2009. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- Richard Crossman (1907–1974), Politician National Portrait Gallery, London

- On Richard Crossman Archived 7 September 2008 at the Wayback Machine CliveJames.com

- Catalogue of Crossman's papers, held at the Modern Records Centre, University of Warwick

- Collection of Crossman's papers available digitally, held at the Modern Records Centre, University of Warwick

- Newspaper clippings about Richard Crossman in the 20th Century Press Archives of the ZBW