In music theory, the syntonic comma, also known as the chromatic diesis, the Didymean comma, the Ptolemaic comma, or the diatonic comma[2] is a small comma type interval between two musical notes, equal to the frequency ratio 81/80 (= 1.0125) (around 21.51 cents). Two notes that differ by this interval would sound different from each other even to untrained ears,[3] but would be close enough that they would be more likely interpreted as out-of-tune versions of the same note than as different notes. The comma is also referred to as a Didymean comma because it is the amount by which Didymus corrected the Pythagorean major third (81/64, around 407.82 cents)[4] to a just / harmonicly consonant major third (5/4, around 386.31 cents).

The word "comma" came via Latin from Greek κόμμα, from earlier *κοπ-μα = "a thing cut off", or "a hair", as in "off by just a hair".

Relationships

editThe prime factors of the just interval 81/80 known as the syntonic comma can be separated out and reconstituted into various sequences of two or more intervals that arrive at the comma, such as 81/1 × 1/80 or (fully expanded and sorted by prime) 3 × 3 × 3 × 3/ 2 × 2 × 2 × 2 × 5 . All sequences of notes that produce that fraction are mathematically valid, but some of the more musical sequences people use to remember and explain the comma's composition, occurrence, and usage are listed below:

- The ratio of the two kinds of major second which occur in 5-limit tuning: the greater tone (9:8, about 203.91 cents, or C ↗ D in just C major) and lesser tone (10:9, about 182.40 cents, or D ↗ E). Namely, 9:8 ÷ 10:9 = 81:80 , or equivalently, sharpening by a comma promotes a lesser major second to a greater second 10/9 × 81/80 = 9/8 .[4]

- The difference in size between a Pythagorean ditone (frequency ratio 81:64, or about 407.82 cents) and a just major third (5:4, or about 386.31 cents). Namely, 81/64 ÷ 5/4 = 81/80 .

- The difference between four justly tuned perfect fifths, and two octaves plus a justly tuned major third. A just perfect fifth has a size of 3:2 (about 701.96 cents), and four of them are equal to 81:16 (about 2807.82 cents). A just major third has a size of 5:4 (about 386.31 cents), and one of them plus two octaves (4:1 or exactly 2400 cents) is equal to 5:1 (about 2786.31 cents). The difference between these is the syntonic comma. Namely, 81:16 ÷ 5:1 = 81:80 .

- The difference between one octave plus a justly tuned minor third (12:5, about 1515.64 cents), and three justly tuned perfect fourths (64:27, about 1494.13 cents). Namely, 12:5 ÷ 64:27 = 81:80.

- The difference between a Pythagorean major sixth (27:16, about 905.87 cents) and a justly tuned or "pure" major sixth (5:3, about 884.36 cents). Namely, 27:16 ÷ 5:3 = 81:80.[4]

On a piano keyboard (typically tuned with 12-tone equal temperament) a stack of four fifths (700 × 4 = 2800 cents) is exactly equal to two octaves (1200 × 2 = 2400 cents) plus a major third (400 cents). In other words, starting from a C, both combinations of intervals will end up at E. Using justly tuned octaves (2:1), fifths (3:2), and thirds (5:4), however, yields two slightly different notes. The ratio between their frequencies, as explained above, is a syntonic comma (81:80). Pythagorean tuning uses justly tuned fifths (3:2) as well, but uses the relatively complex ratio of 81:64 for major thirds. Quarter-comma meantone uses justly tuned major thirds (5:4), but flattens each of the fifths by a quarter of a syntonic comma, relative to their just size (3:2). Other systems use different compromises. This is one of the reasons why 12-tone equal temperament is currently the preferred system for tuning most musical instruments[clarification needed].

Mathematically, by Størmer's theorem, 81:80 is the closest superparticular ratio possible with regular numbers as numerator and denominator. A superparticular ratio is one whose numerator is 1 greater than its denominator, such as 5:4, and a regular number is one whose prime factors are limited to 2, 3, and 5. Thus, although smaller intervals can be described within 5-limit tunings, they cannot be described as superparticular ratios.

Syntonic comma in the history of music

editThe syntonic comma has a crucial role in the history of music. It is the amount by which some of the notes produced in Pythagorean tuning were flattened or sharpened to produce just minor and major thirds. In Pythagorean tuning, the only highly consonant intervals were the perfect fifth and its inversion, the perfect fourth. The Pythagorean major third (81:64) and minor third (32:27) were dissonant, and this prevented musicians from using triads and chords, forcing them for centuries to write music with relatively simple texture.

The syntonic tempering dates to Didymus the Musician, whose tuning of the diatonic genus of the tetrachord replaced one 9:8 interval with a 10:9 interval (lesser tone), obtaining a just major third (5:4) and semitone (16:15). This was later revised by Ptolemy (swapping the two tones) in his "syntonic diatonic" scale (συντονόν διατονικός, syntonón diatonikós, from συντονός + διάτονος). The term syntonón was based on Aristoxenus, and may be translated as "tense" (conventionally "intense"), referring to tightened strings (hence sharper), in contrast to μαλακόν (malakón, from μαλακός), translated as "relaxed" (conventional "soft"), referring to looser strings (hence flatter or "softer").

This was rediscovered in the late Middle Ages, where musicians realized that by slightly tempering the pitch of some notes, the Pythagorean thirds could be made consonant. For instance, if the frequency of E is decreased by a syntonic comma (81:80), C-E (a major third), and E-G (a minor third) become just. Namely, C-E is narrowed to a justly intonated ratio of

and at the same time E-G is widened to the just ratio of

The drawback is that the fifths A-E and E-B, by flattening E, become almost as dissonant as the Pythagorean wolf fifth. But the fifth C-G stays consonant, since only E has been flattened (C-E × E-G = 5/4 × 6/5 = 3/2), and can be used together with C-E to produce a C-major triad (C-E-G). These experiments eventually brought to the creation of a new tuning system, known as quarter-comma meantone, in which the number of major thirds was maximized, and most minor thirds were tuned to a ratio which was very close to the just 6:5. This result was obtained by narrowing each fifth by a quarter of a syntonic comma, an amount which was considered negligible, and permitted the full development of music with complex texture, such as polyphonic music, or melody with instrumental accompaniment. Since then, other tuning systems were developed, and the syntonic comma was used as a reference value to temper the perfect fifths in an entire family of them. Namely, in the family belonging to the syntonic temperament continuum, including meantone temperaments.

Comma pump

editThe syntonic comma arises in comma pump (comma drift) sequences such as C G D A E C, when each interval from one note to the next is played with certain specific intervals in just intonation tuning. If we use the frequency ratio 3/2 for the perfect fifths (C-G and D-A), 3/4 for the descending perfect fourths (G-D and A-E), and 4/5 for the descending major third (E-C), then the sequence of intervals from one note to the next in that sequence goes 3/2, 3/4, 3/2, 3/4, 4/5. These multiply together to give

which is the syntonic comma (musical intervals stacked in this way are multiplied together). The "drift" is created by the combination of Pythagorean and 5-limit intervals in just intonation, and would not occur in Pythagorean tuning due to the use only of the Pythagorean major third (64/81) which would thus return the last step of the sequence to the original pitch.

So in that sequence, the second C is sharper than the first C by a syntonic comma ⓘ. That sequence, or any transposition of it, is known as the comma pump. If a line of music follows that sequence, and if each of the intervals between adjacent notes is justly tuned, then every time the sequence is followed, the pitch of the piece rises by a syntonic comma (about a fifth of a semitone).

Study of the comma pump dates back at least to the sixteenth century when the Italian scientist Giovanni Battista Benedetti composed a piece of music to illustrate syntonic comma drift.[5]

Note that a descending perfect fourth (3/4) is the same as a descending octave (1/2) followed by an ascending perfect fifth (3/2). Namely, (3/4) = (1/2) × (3/2). Similarly, a descending major third (4/5) is the same as a descending octave (1/2) followed by an ascending minor sixth (8/5). Namely, (4/5) = (1/2) × (8/5). Therefore, the above-mentioned sequence is equivalent to:

or, by grouping together similar intervals,

This means that, if all intervals are justly tuned, a syntonic comma can be obtained with a stack of four perfect fifths plus one minor sixth, followed by three descending octaves (in other words, four P5 plus one m6 minus three P8).

Notation

editMoritz Hauptmann developed a method of notation used by Hermann von Helmholtz. Based on Pythagorean tuning, subscript numbers are then added to indicate the number of syntonic commas to lower a note by. Thus a Pythagorean scale is C D E F G A B, while a just scale is C D E1 F G A1 B1. Carl Eitz developed a similar system used by J. Murray Barbour. Superscript positive and negative numbers are added, indicating the number of syntonic commas to raise or lower from Pythagorean tuning. Thus a Pythagorean scale is C D E F G A B, while the 5-limit Ptolemaic scale is C D E−1 F G A−1 B−1.

In Helmholtz-Ellis notation, a syntonic comma is indicated with up and down arrows added to the traditional accidentals. Thus a Pythagorean scale is C D E F G A B, while the 5-limit Ptolemaic scale is C D E F G A B .

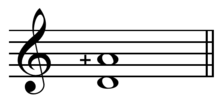

Composer Ben Johnston uses a "−" as an accidental to indicate a note is lowered by a syntonic comma, or a "+" to indicate a note is raised by a syntonic comma.[1] Thus a Pythagorean scale is C D E+ F G A+ B+, while the 5-limit Ptolemaic scale is C D E F G A B.

| 5-limit just | Pythagorean | |

|---|---|---|

| HE | C D E F G A B | C D E F G A B |

| Johnston | C D E F G A B | C D E+ F G A+ B+ |

See also

editReferences

edit- ^ a b John Fonville. "Ben Johnston's Extended Just Intonation – A Guide for Interpreters", p. 109, Perspectives of New Music, vol. 29, no. 2 (Summer 1991), pp. 106-137. and Johnston, Ben and Gilmore, Bob (2006). "A Notation System for Extended Just Intonation" (2003), "Maximum clarity" and Other Writings on Music, p. 78. ISBN 978-0-252-03098-7.

- ^ Johnston, B. (2006), Gilmore, B. (ed.), "Maximum Clarity" and Other Writings on Music, Urbana, IL: University of Illinois Press, ISBN 0-252-03098-2

- ^ "Sol-Fa – The Key to Temperament", bbc.co.uk, BBC, archived from the original on February 8, 2005

- ^ a b c Lloyd, Llewelyn Southworth (1937), Music and Sound, Books for Libraries Press, p. 12, ISBN 0-8369-5188-3

- ^ a b Wild, Jonathan; Schubert, Peter (Spring–Fall 2008), "Historically Informed Retuning of Polyphonic Vocal Performance" (PDF), Journal of Interdisciplinary Music Studies, 2 (1&2): 121–139 [127], archived from the original (PDF) on September 11, 2010, retrieved April 5, 2013, art. #0821208.