Delaney & Bonnie was an American duo of singer-songwriters Delaney Bramlett and Bonnie Bramlett. In 1969 and 1970, they fronted a rock/soul ensemble, Delaney & Bonnie and Friends, whose members at different times included Duane Allman, Gregg Allman, Eric Clapton, George Harrison, Leon Russell, Bobby Whitlock, Dave Mason, Steve Howe, Rita Coolidge, and King Curtis.

Delaney & Bonnie | |

|---|---|

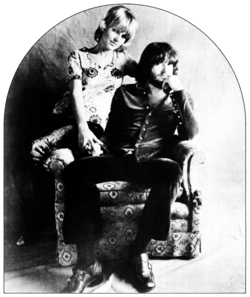

Delaney & Bonnie in 1970, during the making of their album To Bonnie from Delaney | |

| Background information | |

| Origin | Los Angeles, California, US |

| Genres | |

| Years active | 1967–1972 |

| Labels | Stax, Elektra, Atco, Columbia/CBS, Rhino |

| Past members | Delaney Bramlett Bonnie Bramlett Duane Allman Gregg Allman Leon Russell Carl Radle Jim Gordon Jim Price Darrell Leonard Dave Mason David Marks Rita Coolidge King Curtis Eric Clapton Bobby Whitlock Jim Keltner Bobby Keys Gram Parsons George Harrison Ben Benay Kenny Gradney Jay York |

Background

editDelaney Bramlett (July 1, 1939, Pontotoc County, Mississippi – December 27, 2008, Los Angeles) learned the guitar in his youth. He moved to Los Angeles in 1959,[1] where he became a session musician. His most notable early work was as a member of the Shindogs, the house band for the ABC-TV series Shindig! (1964–66), which also included guitarist and keyboardist Leon Russell.[2] He was the first artist signed to Independence Records. His debut single "Guess I Must be Dreamin" was produced by Russell.[3]

Bonnie Bramlett (née Bonnie Lynn O'Farrell, born November 8, 1944, in Granite City, Illinois) was an accomplished singer at an early age, performing when she was 14 years old with blues guitarist Albert King and in the Ike & Tina Turner Revue—the first white Ikette.[4] She moved to Los Angeles in 1967 and met and married Bramlett later that year.[5]

Career

editBeginnings and Stax contract

editDelaney Bramlett and Leon Russell had many connections in the music business through their work in the Shindogs and formed a band of solid, if transient, musicians around Delaney & Bonnie. The band became known as "Delaney & Bonnie and Friends", because of its regular changes of personnel. They secured a recording contract with Stax Records and completed work on their first album, Home, in 1968. In his 2007 autobiography, Eric Clapton erroneously[original research?] states that Delaney & Bonnie and Friends were the first white group to sign a contract with Stax.[6] Despite production and session assistance from Donald "Duck" Dunn, Isaac Hayes, and other Stax mainstays of the era, the album was not successful—perhaps because of poor promotion, as it was one of 27 albums simultaneously released by Stax in that label's initial attempt to establish itself in the album market.[7]

Elektra and Apple contracts

editDelaney and Bonnie moved to Elektra Records for their second album, The Original Delaney & Bonnie & Friends (Accept No Substitute) (1969). While not a big seller either, it created a buzz in music industry circles when, upon hearing pre-release mixes of the album, George Harrison offered Delaney and Bonnie a contract with the Beatles' Apple Records label—which Delaney and Bonnie signed despite their prior contractual commitment to Elektra. The Apple contract was subsequently voided, but this incident began a falling-out between Delaney and Elektra.[8] Delaney and Bonnie were released from their Elektra contract in late 1969, after Delaney threatened to kill Elektra founder Jac Holzman because their album wasn't on sale in the town where his father lived.[9]

Atco contract and chart success

editOn the strength of Accept No Substitute, and at his friend Harrison's suggestion,[10] Eric Clapton took Delaney & Bonnie and Friends on the road in mid-1969 as the opening act for the supergroup he had formed, Blind Faith. Clapton quickly became friends with Delaney, Bonnie and their band, preferring their music to Blind Faith's. Impressed by their live performances, he would often appear on stage with Delaney & Bonnie and Friends during this period, and he continued to record and tour with them following Blind Faith's August 1969 breakup. Clapton helped broker a new record deal for Delaney and Bonnie with his then-US label, Atco (Atlantic) Records, and performed (with Harrison, Dave Mason, and others) on Delaney and Bonnie's third album, the live On Tour with Eric Clapton (Atco; recorded in the UK, December 7, 1969, and released in North America in March 1970). This album would be their most successful, reaching No. 29 on the Billboard 200,[11] and achieving RIAA gold record status. Clapton also recruited Delaney and Bonnie and their band to back him on his debut solo album, recorded in late 1969 and early 1970 and produced by Delaney.

Delaney and Bonnie continued to make well-regarded, if modest selling, albums over the rest of their career. "Soul Shake" (a cover of Soulshake by Peggy Scott & Jo Jo Benson from 1969) from To Bonnie from Delaney (1970) peaked at number 43 on the Hot 100 on September 19, 1970, and "Never Ending Song of Love", from the mostly acoustic album Motel Shot (1971), reached number 13 on the Hot 100 from July 24 to 14, 1971, and was Billboard's number 67 single of 1971. The band's other notable activities during this period include participation (with the Grateful Dead, the Band and Janis Joplin) on the 1970 Festival Express tour of Canada, with an appearance at the Strawberry Fields Festival; an appearance in Richard C. Sarafian's 1971 film Vanishing Point, contributing the song "You Got to Believe" to its soundtrack; and a July 1971 live show broadcast by New York's WABC-FM (now WPLJ), backed by Duane Allman, Gregg Allman and King Curtis. (A song from the latter set, "Come On in My Kitchen," is included on the 1974 Duane Allman compilation album An Anthology Vol. II.)

CBS contract and breakup

editBy late 1971, Delaney and Bonnie's often tempestuous relationship began to show signs of strain.[12] Bonnie described their relationship as abusive due to their cocaine addictions, and they fought often.[5] Their next album, Country Life, was rejected by Atco on grounds of poor quality,[13] and Atco/Atlantic elected to sell Delaney and Bonnie's recording contract—including this album's master tapes—to CBS Records. Columbia released this album, in a different track sequence from that submitted to Atco, as D&B Together, in March 1972. It was Delaney and Bonnie's last album of new material. They divorced in 1972.[5]

Legacy

editLive success

editDelaney and Bonnie are generally best remembered for their albums On Tour with Eric Clapton and Motel Shot. On Tour was their best-selling album by far, and is (except for their version of "Come On in My Kitchen" with Duane Allman, released after Delaney and Bonnie's breakup and Allman's death) the only official document of their live work.[citation needed] Delaney and Bonnie were considered by many to be at their best on stage. In his autobiography, Atlantic Records executive Jerry Wexler stated that the studio album he produced for the band, To Bonnie from Delaney, "didn't quite catch the fire of their live performances."[14] Clapton makes an even stronger statement in his autobiography: "For me, going on [with Blind Faith] after Delaney and Bonnie was really, really tough, because I thought they were miles better than us."[15] Motel Shot, although technically a studio album, was largely recorded "live in the studio" with acoustic instruments — a rarity for rock bands at the time.[citation needed]

Influence

editIn addition to having produced a rich recorded legacy, Delaney and Bonnie influenced many fellow musicians of their era. Most notably, Clapton has said: "Delaney taught me everything I know about singing,"[16] and Delaney has been cited as the person who taught George Harrison how to play slide guitar,[17] a technique Harrison used to great effect throughout his solo recording career. Bonnie, for her part, is credited (with Delaney, Clapton and/or Leon Russell) as co-author of various popular songs, including "Groupie (Superstar)" (a Top 10 hit for The Carpenters in 1971; also covered by ex-Delaney and Bonnie backing vocalist Rita Coolidge, Bette Midler, Sonic Youth, and many others) and Clapton's "Let It Rain." (Bonnie's song authorship became a matter of dispute in the last years of Delaney's life, with Delaney claiming he wrote many of these songs but assigned ownership to Bonnie to dodge an onerous publishing contract[18] - an assertion supported, indirectly, through statements made by Clapton.[19][20] Many songs that Bonnie Bramlett contributed to during the band's tenure, but for which Delaney Bramlett was not originally credited, now list both Bramletts as co-authors in BMI's Repertoire database.)[21]

Friends

editDelaney and Bonnie's "Friends" of the band's 1969-70 heyday also had considerable impact. After the early 1970 breakup of this version of the band, Leon Russell recruited many of its ex-members, excepting Delaney, Bonnie and singer/keyboardist Bobby Whitlock, to join Joe Cocker's band, participating on Cocker's Mad Dogs & Englishmen recording sessions and North American tour (March–May 1970; Rita Coolidge's version of "Groupie (Superstar)" was recorded with this band while on tour). Whitlock meanwhile joined Clapton at his home in Surrey, UK, where they wrote songs and decided to form a band, which two former "Friends"/Cocker band members, bassist Carl Radle and drummer Jim Gordon, would later join. As Derek and the Dominos, they recorded the landmark album Layla and Other Assorted Love Songs (1970) with assistance on many tracks from another former "Friend," lead/slide guitarist Duane Allman. Derek and the Dominos also constituted the core backing band on George Harrison's solo debut album All Things Must Pass (1970) with assistance from still more former "Friends": Dave Mason, Bobby Keys and Jim Price.[citation needed]

Discography

editAlbums

edit- Home (Stax, 1969)

- Accept No Substitute, previously entitled The Original Delaney & Bonnie (Elektra, 1969)

- On Tour with Eric Clapton (Atco, 1970)

- To Bonnie from Delaney (Atco, 1970)

- Motel Shot (Atco, 1971)

- Country Life (Atco, 1972)

- D&B Together (Columbia, 1972), reissue of Country Life

- The Best of Delaney & Bonnie (Atco, 1972)

- The Best of Delaney & Bonnie (Rhino, 1990)

Chart performance

editAlbums

edit| Year | Album | Peak chart

positions |

Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| US[citation needed] | |||

| 1969 | Home | — | |

| Accept No Substitute | 175 | ||

| 1970 | On Tour with Eric Clapton | 29 | Live album |

| To Bonnie from Delaney | 58 | ||

| 1971 | Motel Shot | 65 | |

| 1972 | Country Life | — | |

| D&B Together | 133 | Reissue of Country Life | |

| The Best of Delaney & Bonnie | — | Compilation album | |

| "—" denotes releases that did not chart | |||

Singles

edit| Year | Single | Peak chart positions | |

|---|---|---|---|

| US | AUS [22] | ||

| 1969 | "It's Been a Long Time Coming" | — | — |

| "Hard to Say Goodbye" | 138* | — | |

| "When The Battle Is Over" | — | — | |

| 1970 | "Comin Home" | 84 | 49 |

| "Soul Shake" | 43 | — | |

| "Free the People" | 75 | — | |

| "They Call it Rock & Roll Music" | 119 | — | |

| 1971 | "Never Ending Song of Love" | 13 | 16 |

| "Only You Know and I Know" | 20 | 85 | |

| 1972 | "Move Em Out" | 59 | — |

| "Where There’s a Will There’s a Way" | 99 | — | |

| "—" denotes releases that did not chart

* Record World Singles Chart[23] | |||

In addition, GNP Crescendo Records (US) and London Records (UK) released an album of 1964–65 and 1967 recordings by Delaney Bramlett in 1971 as Delaney & Bonnie: Genesis. While not a Delaney & Bonnie album per se, Bonnie Bramlett does appear with Delaney on three of this album's twelve selections.

References

edit- ^ Martin, Greg (2002). Liner notes to the 2003 reissue of Delaney & Bonnie's album D&B Together, Columbia/Legacy/Sony Music, catalog no. CK 85743.

- ^ "YouTube". YouTube. Retrieved October 14, 2019.[dead YouTube link]

- ^ "First Disk Bowed By Indep'dence" (PDF). Billboard. April 8, 1967. p. 16.

- ^ Holzman, Jac, and Gavan Daws (1998). Follow the Music: The Life and High Times of Elektra Records in the Great Years of American Pop Culture, FirstMedia, ISBN 0-9661221-1-9, p. 271.

- ^ a b c Dougherty, Steve (April 13, 1992). "A '70s Burnout Lights Up Roseanne". People.com.

- ^ Clapton, Eric (2007) Eric Clapton: The Autobiography, Broadway, ISBN 978-0-7679-2842-7, p. 111. Clapton's statement is faulty, as the racially integrated instrumental group the Mar-Keys recorded for Stax as early as 1961. Delaney and Bonnie were among the few white singers to record for the label, however.

- ^ Bowman, Rob (1997). Soulsville, U.S.A.: The Story of Stax Records, Schirmer, ISBN 0-02-860268-4, p. 175.

- ^ Holzman, Jac, and Gavan Daws. Follow the Music: The Life and High Times of Elektra Records in the Great Years of American Pop Culture, p. 275.

- ^ Goodman, Fred (March 4, 2011). "Indie-Label Folkie to Rock Patriarch". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2020-11-09.

- ^ Hjort, Christopher (2007). Strange Brew: Eric Clapton and the British Blues Boom, 1965–1970, Jawbone, ISBN 978-1-906002-00-8, p. 250.

- ^ "Delaney & Bonnie Chart History". Billboard. Archived from the original on November 10, 2019.

- ^ Holzman, Jac, and Gavan Daws. Follow the Music: The Life and High Times of Elektra Records in the Great Years of American Pop Culture, p. 274.

- ^ Wexler, Jerry, and David Ritz (1993). Rhythm and the Blues, Knopf, ISBN 0-679-40102-4, p. 263.

- ^ Wexler and Ritz (1993). Rhythm and the Blues, p. 253.

- ^ Clapton, Eric (2007). Clapton - The Autobiography, Broadway, ISBN 978-0-385-51851-2, p. 113.

- ^ Wexler and Ritz (1993). Rhythm and the Blues, p. 254.

- ^ "George Harrison". Rock & Roll Hall of Fame. Retrieved October 14, 2019.

- ^ Hjort, Christopher. Strange Brew: Eric Clapton and the British Blues Boom, 1965–1970, p. 282.

- ^ Roberty, Mark (1993). Eric Clapton: The Complete Recording Sessions, 1963–1992, Blandford (UK)/St. Martin's (US), ISBN 0-312-09798-0, pp. 54–55.

- ^ Clapton, Eric. Clapton - The Autobiography, p. 120.

- ^ "BMI | Repertoire Search". March 3, 2017. Archived from the original on March 3, 2017. Retrieved October 14, 2019.

- ^ Kent, David (1993). Australian Chart Book 1970–1992 (illustrated ed.). St Ives, N.S.W.: Australian Chart Book. p. 87. ISBN 0-646-11917-6.

- ^ Whitburn, Joel (2015). The Comparison Book Billboard/Cash Box/Record World 1954–1982. Sheridan Books. p. 139. ISBN 978-0-89820-213-7.