This article needs additional citations for verification. (June 2016) |

Martyrs' Day (Spanish: Día de los Mártires) is a Panamanian day of national mourning which commemorates the January 9, 1964 anti-American riots over sovereignty of the Panama Canal Zone. The riot started after a Panamanian flag was torn and students were killed during a conflict with Canal Zone Police officers and Canal Zone residents. It is also known as the Flag Incident or Flag Protests.

U.S. Army units became involved in suppressing the violence after Canal Zone police were overwhelmed, and after three days of fighting, about 22 Panamanians and four U.S. soldiers were killed. The incident is considered to be a significant factor in the U.S. decision to transfer control of the Canal Zone to Panama through the 1977 Torrijos–Carter Treaties.

Background

editThis section relies largely or entirely on a single source. (June 2016) |

After Panama gained independence from Colombia in 1903, with the assistance of the U.S., there was resentment amongst some Panamanians as a result of the Hay–Bunau-Varilla Treaty, which ceded control of the Panama Canal Zone to the U.S. "in perpetuity" in exchange for a 10 million dollar initial payment and yearly 250 thousand dollar payments thereafter. In addition, the United States Government purchased title to all the lands in the Canal Zone from the private owners. The Canal Zone, primarily consisting of the Panama Canal, was a strip of land running from the Pacific Ocean to the Caribbean and had its own police, schools, ports and post offices. The Canal Zone became U.S. territory (de facto if not de jure). According to Stephen Bosworth the American Principal Officer in Colon, "there were several thousand families in the Canal Zone. Many of them had been there for two and three generations. They operated, administered, and maintained the Canal, which at that point was a very important waterway. Many of them had become very inward looking, very chauvinistic, and did not like Panamanians or Panama. Many of them had lived in this ten-mile wide strip of land for nearly their whole lives and had never set foot in the Republic of Panama. Anything the U.S. gave up with regard to sovereignty over the Canal Zone was a loss to them. They were American colonials. In fact, they were in this little American enclave, very well paid, lived very well, very generous fringe benefits and they recognized that as the Panamanians took control of the Canal that they would lose."[1] This group was commonly referred to as Zonians.

In January 1963, U.S. President John F. Kennedy agreed to fly Panama's flag alongside the U.S. flag at all non-military sites in the Canal Zone where the U.S. flag was flown. However, Kennedy was assassinated before his orders were carried out. One month after Kennedy's death, Panama Canal Zone Governor Robert J. Fleming, Jr. issued a decree limiting Kennedy's order. The U.S. flag would no longer be flown outside Canal Zone schools, police stations, post offices or other civilian locations where it had been flown, but Panama's flag would not be flown either. The governor's order infuriated many Zonians, who interpreted it as a U.S. renunciation of sovereignty over the Canal Zone.[2]

In response, outraged Zonians began flying the U.S. flag anywhere they could. After the first U.S. flag to be raised at Balboa High School (a public high school in the Canal Zone) was taken down by school officials, the students walked out of class, raised another flag, and posted guards to prevent its removal. Most Zonian adults sympathized with the student demonstrators.

In what was to prove a miscalculation of the volatility of the situation, Governor Fleming departed for a meeting in Washington, D.C., on the afternoon of January 9, 1964. For him and many others, the U.S.–Panama relationship was at its peak. The exploding situation caught up with the Governor while he was still en route to the U.S. over the Caribbean.

The Flag Pole Incident

editThis section relies largely or entirely on a single source. (June 2016) |

While a Panamanian response to the flag raisings by the Zonians was expected, the crisis took most Americans by surprise. Several years later, Lyndon B. Johnson wrote in his memoirs that: "When I heard about the students' action, I was certain we were in for trouble."[citation needed]

The news of the actions of the Balboa High School reached the students at the Instituto Nacional, Panama's top public high school. Led by 17-year-old Guillermo Guevara Paz, 150 to 200 demonstrating students from the institute, crossed the street into the Canal Zone and marched through the neighborhoods to Balboa High School, carrying their school's Panamanian flag and a sign proclaiming their country's sovereignty over the U.S. Canal Zone. They had first informed their school principal and the Canal Zone authorities of their plans before setting out on their march. Their intention was to raise the Panamanian flag on the Balboa High School flagpole, alongside the U.S. flag.

At Balboa High, the Panamanian students were met by Canal Zone police and a crowd of Zonian students and adults. After negotiations between the Panamanian students and the police, a small group was allowed to approach the flagpole, while police kept the main group back.[citation needed]

A half-dozen Panamanian students, carrying their flag, approached the flagpole. In response, the Zonians surrounded the flagpole, sang "The Star-Spangled Banner" and rejected the deal between the police and the Panamanian students. Scuffling broke out. The Panamanians were driven back by the Zonian civilians and police. In the course of the scuffle, Panama's flag was torn.

The flag in question had historical significance. In 1947, students from the Instituto Nacional had carried it in demonstrations opposing the Filos-Hines Treaty and demanding the withdrawal of U.S. military bases. Independent investigators of the events of January 9, 1964 later noted that the flag was made of flimsy silk.[2]

There are conflicting claims about how the flag was torn. Canal Zone Police Captain Gaddis Wall, who was in charge of the police at the scene, denies any American culpability. He claims that the Panamanian students stumbled and accidentally tore their own flag. David M. White, an apprentice telephone technician with the Panama Canal Company, stated that "the police gripped the students, who were four or five abreast, under the shoulders in the armpits and edged them forward. One of the students fell or tripped and I believe when he went down the old flag was torn." None of these accounts have been definitively proven.

One of the Panamanian flag bearers, Eligio Carranza, said that "they started shoving us and trying to wrest the flag from us, all the while insulting us. A policeman wielded his club which ripped our flag. The captain tried to take us where the others Panamanian students were. On the way through the mob, pulled and tore our flag."

To this day, the issue remains highly contentious, with both sides saying the other instigated the conflict.

Violence breaks out

editThis section relies largely or entirely on a single source. (June 2016) |

As word of the flag desecration incident spread, angry Panamanian crowds formed along and across the border between Panama City and the Canal Zone. At several points demonstrators stormed into the zone, planting Panamanian flags. Canal Zone police tear gassed them. Rocks were thrown, causing injuries to several of the police officers. The police responded by opening fire.

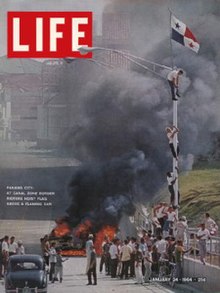

Canal Zone authorities asked the Panama National Guard (Panama's Armed Forces) to suppress the disturbances, but they did not intervene. Meanwhile, demonstrators began to tear down the "Fence of Shame" located in the Canal Zone, a safety feature alongside a busy highway. Panamanians were tear gassed, and then several were shot. One of the most famous photographs of what Panamanians know as Martyrs' Day shows two demonstrators, one bearing a Panamanian flag, climbing over Fence of Shame at Ancon. The opinion of most Panamanians, and most Latin Americans generally, about the fence in question was expressed a few days later by Colombia's ambassador to the Organization of American States: "In Panama there exists today another Berlin Wall."

The Panamanian crowds grew as nightfall came, and by 8 p.m. the Canal Zone Police was overwhelmed. Some 80 to 85 police officers faced a hostile crowd of at least 5,000, and estimated by some sources to be 30,000 or more, all along and across the border between Panama City and the Canal Zone. When the lieutenant governor came to survey the scene, the protestors stoned his car.

At the request of Lieutenant Governor Parkers, General Andrew P. O'Meara, commander of the U.S. Southern Command, assumed authority over the Canal Zone. The U.S. Army's 193rd Infantry Brigade was deployed at about 8:35 p.m.

American-owned businesses in Panama City were set afire. The recently dedicated Pan Am building (which, despite housing an American corporation, was Panamanian-owned) was completely gutted. The next morning, the bodies of six Panamanians were found in the wreckage.

Some reporters alleged one giant communist plot, with Christian Democrats, Socialists, student government leaders and a host of others controlled by the hand of Fidel Castro. However, it seems that Panama's communists were caught by surprise by the outbreak of violence and commanded the allegiance of only a small minority of those who rioted on the Day of the Martyrs. A good indication of the relative communist strength came two weeks after the confrontations, when the Catholic Church sponsored a memorial rally for the fallen, which was attended by some 40,000 people. A rival communist commemoration on the same day drew only 300 participants.

The US Embassy was ordered to burn all sensitive documents. A number of U.S. citizen residents of Panama City, particularly military personnel and their families who were unable to get housing on base, were forced to flee their homes. There were many instances in which Panamanians gave refuge to Americans who were endangered in Panama City and elsewhere.

The confrontation was not contained in the Panama City area. Word of the fighting quickly spread all over Panama by radio, television and private telephone calls. The incomplete censorship had the side effect of contributing to wild rumors on all sides. One popular but inaccurate Zonian rumor, fueled in part by references to the "American Canal Zone" in U.S. news media, alleged that the Panama Canal Zone had been renamed "United States Canal Zone" and would henceforth be an outright possession of the United States.[citation needed]

News and rumor instantly traveled the 49 miles (79 km) from Panama's south coast to its north coast. The country's second city, Colón, which abuts the city of Cristóbal, then part of the Canal Zone, erupted within a few hours after the start of hostilities on the Pacific side. Intense fighting continued for the next two days. Unlike in Panama City, Panamanian authorities in Colón had made early attempts to separate the combatants. Some incidents also happened in other cities all over Panama.

Death toll

editThis section relies largely or entirely on a single source. (June 2016) |

As the angry Panamanian mob turned their wrath against targets in Panama City, a number of people were shot to death under controversial circumstances. The final death toll was 28 people.

Ascanio Arosemena, a 19-year-old student, was shot from behind, through the shoulder and thorax. He became the first of Panama's "martyrs," as those who fell on January 9, 1964, and the following few days were to become known. Witnesses say that Arosemena died while helping to evacuate wounded protesters from the danger zone. The witnesses appear to be corroborated by a photograph of Arosemena supporting an injured man, said to have been taken shortly before he was shot. The building where it all started, the former Balboa High School today bears his name, and is one of the buildings of the Panama Canal Authority, the Panamanian Government Agency created to run the Canal starting from mid-day December 31, 1999.

A six-month-old girl, Maritza Ávila Alabarca, died with respiratory problems while her neighborhood was gassed by the U.S. Army with CS tear gas. The U.S. denied that the infant's death was linked to the use of CS tear gas, in keeping with its claim that it is not a lethal agent.

Various U.S. accounts claim that all Panamanians who were shot to death were either rioters or else shot by other Panamanians.

Various Panamanian versions blame all Panamanian deaths on U.S. forces, though those who died in the Pan American Airlines building fire can not reasonably be said to have died at the hands of American forces. Some Panamanians may have been hit by bullets fired by Panamanians but intended for American targets.[citation needed] A definitive accounting of all deaths in the events of January 1964 has yet to be published, and may never be published.

The official Canal Zone Police version is that the police did not shoot directly at anybody, but only fired over the heads or at the feet of rioters. The police version was disputed by independent investigators, who found that the police fired directly into the crowds and killed Arosemena and a number of other Panamanians. DENI ballistics experts claim that six Panamanians were killed by .38 caliber Smith & Wesson police revolvers fired by the Canal Zone Police.

The list of Panama's martyrs can be found at the martyrs Memorial in the former Balboa High School in Panama City. The 21 as listed there include: Maritza Ávila Alabarca, Ascanio Arosemena, Rodolfo Sánchez Benítez, Luis Bonilla, Alberto Constance, Gonzalo Crance, Teofilo De La Torre, José Del Cid, Victor Garibaldo, José Gil, Ezequiel González, Victor Iglesias, Rosa Landecho, Carlos Lara, Gustavo Lara, Ricardo Murgas, Estanislao Orobio, Jacinto Palacios, Ovidio Saldaña, Alberto Tejada and Celestino Villarreta.

Most U.S. accounts put the number of Americans killed in these events at four, though others put the death toll at three or five. Those who died on the American side include Staff Sergeant Luis Jimenez Cruz, Private David Haupt and First Sergeant Gerald Aubin [Company C, 4th Battalion, 10th Infantry] who were all killed by sniper fire on the 9th and 10th in Colon and Specialist Michael W. Rowland (3rd Battalion, 508th Airborne Infantry), whose death was caused by an accidental fall into a ravine on the evening of the 10th.

Another 30 U.S. military personnel were wounded in operations to separate the Panamanian and Canal Zone protesters. Most of the 17 injuries suffered by U.S. civilians resulted from thrown rocks or bottles.[4][5]

When the fighting was over, DENI investigators found over 600 bullets embedded in the Legislative Palace. Santo Tomas Hospital reported that it had treated 324 injuries and recorded 18 deaths from the fighting. Panama City's Social Security Hospital treated at least 16 others who were wounded on the first night of the fighting. Most of those killed and wounded had suffered gunshot wounds. Some of the more seriously injured were left with severe permanent brain damage or paralyzing spinal injuries from their bullet wounds.

After the fighting, American investigators found over 400 bullets embedded in the Tivoli Hotel. Years after the events of January 1964, a number of U.S. Army historical documents were declassified, including Southcom's figures for ammunition expended. The official account has it that the U.S. Army fired 450 .30 caliber rifle rounds, five .45 caliber pistol bullets, 953 shells of birdshot and 7,193 grenades or projectiles containing tear gas. Also, the army claims to have used 340 pounds of bulk CN-1 chemical (weak tear gas) and 120 pounds of CS-1 chemical (strong tear gas). The same account said that the Canal Zone police fired 1,850 .38 caliber pistol bullets and 600 shotgun shells in the fighting, while using only 132 tear gas grenades. According to the Panamanian DENI, out of the 1,850 .38 caliber bullets that the Canal Zone Police allegedly fired directly into the crowd, only six Panamanians were fatally wounded. Of the remaining 2,008 bullets, shells and rounds, the 7,193 tear gas grenades or projectiles, the additional 460 pounds of tear gas, only 15 Panamanians were fatally wounded.

International reactions and aftermath

editInternational reaction was largely unfavorable against the United States. The British and French governments, who had been criticized by U.S. administrations for their foreign policy and handling of their various colonies, accused the U.S. of hypocrisy and argued that their Zonian citizens were as obnoxious as any other group of colonial settlers.

Egypt's Gamal Abdul Nasser suggested that Panama nationalize the Panama Canal, as Egypt had nationalized the Suez Canal. The communist governments of the Soviet Union, China, and Cuba denounced the U.S. in very strong terms.

Significantly, other governments in the western hemisphere which had long backed U.S. policies declined to back the American position. Venezuela led a chorus of Latin American criticism of the United States. The Organization of American States, on Brazil's motion, took jurisdiction over the dispute from the United Nations Security Council. The OAS in turn put the matter before its Inter-American Peace Committee. The committee held a week-long investigation in Panama which was greeted by a unanimous 15-minute Panamanian work stoppage to demonstrate Panama's united opinion. No action was taken on Panama's motion to brand the United States guilty of aggression, but the committee did accuse the Americans of using unnecessary force.

The President of Panama at the time, Roberto Chiari, broke diplomatic relations with the United States on January 10. On January 15, President Chiari declared that Panama would not re-establish diplomatic ties with the U.S. until it agreed to open negotiations on a new treaty. The first steps in that direction were taken shortly thereafter on April 3, 1964, when both countries agreed to an immediate resumption of diplomatic relations and the United States agreed to adopt procedures for the "elimination of the causes of conflict between the two countries". A few weeks later, Robert B. Anderson, President Johnson's special representative, flew to Panama to pave the way for future talks. For these actions, President Chiari is regarded as "the president of dignity". The role played by the Panamanian ambassador to the United Nations, Miguel Moreno is also worth mentioning. Moreno is remembered for his strong speech against the United States at the UN General Assembly.

This incident is considered to be the catalyst for the eventual U.S. abolition of the "in perpetuity" control of the Canal Zone and divestiture of its title to property there, with the 1977 signing of the Torrijos–Carter Treaties, which dissolved the Canal Zone in 1979, set a timetable for the closing of U.S. Armed Forces Bases and transferred full control of the Panama Canal to the Panamanian Government at noon, December 31, 1999.

Monuments

editThis section relies largely or entirely on a single source. (June 2016) |

Two monuments have been built in Panama City to commemorate these events. One was built where the flagpole incident happened, the former Balboa High School, today a Panama Canal Authority building that bears the name of Ascanio Arosemena, known as the first "martyr" and maybe the most famous one. It was built by the Panama Canal Authority and consists on a covered entryway containing the memorial, which has a name of a "martyr" on each column, and an eternal fire (not unlike the eternal fire for U.S. President John F. Kennedy) in the middle, and the Panamanian flag afterwards, in a sort of open-to-the-sky (i.e. no roof) "square", on a flagpole.

Another monument, built in front of the Legislative Assembly, on the former Panama City-Canal Zone limits consists on a life-sized monument in the form of a lamppost, with three figures climbing it to raise their flag. The monument reflects the photograph that was on the cover of Life, in which three students scaled the 3.7-metre (12 ft) high safety fence and climbed a lamppost and the one in the top had a Panamanian flag.[6]

References

edit- ^ "The Panama Riots of 1964: The Beginning of the End for the Canal". www.adst.org. Retrieved 25 April 2022.

- ^ a b "Archived copy". www.blythe.org. Archived from the original on 6 February 2006. Retrieved 17 January 2022.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ "Flag Demonstration on the boundary between Panama and the Canal Zone". University of Florida Digital Collections. University of Florida.

- ^ "Archived copy". www.blythe.org. Archived from the original on 11 March 2007. Retrieved 17 January 2022.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ "Jackson, Remembering the Day of the Martyrs and its lessons". Archived from the original on 2007-01-26. Retrieved 2007-01-09.

- ^ "Archived copy" (PDF). ediciones.prensa.com. Archived from the original (PDF) on 4 July 2007. Retrieved 17 January 2022.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

External links

edit- The 'Day of the martyrs' - January 9, 1964

- Dean Rusk interview: Lyndon Johnson Presidential Library (see page 37)

- Study by Uwe Heinrich Documents the chemistry of CS and its effects on the body. March 09, 2006

- Why Today Is an Anti-American Holiday in Panama[permanent dead link]

- University of Florida Digital Collections: Panama and the Canal