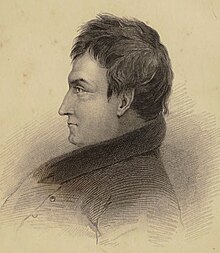

David Nelson (September 24, 1793 – October 17, 1844) was an American Presbyterian minister, physician, and antislavery activist who founded Marion College and served as its first president. Marion College, a Protestant manual labor college, was the first institution of higher learning chartered in the state of Missouri. Born in Tennessee, Dr. Nelson had once been a slaveholder but became an "incandescent" abolitionist after hearing a speech by Theodore D. Weld. Unpopular with proslavery groups in northeastern Missouri, Nelson stepped down as president of Marion College in 1835. In 1836, Nelson fled Missouri for Quincy, Illinois, after slaveowner Dr. John Bosely was stabbed at one of his sermons. Nelson then remained in Quincy, where he founded the Mission Institute to educate young missionaries. Openly abolitionist, two Mission Institute sites became well known stations on the Underground Railroad, helping African Americans escape to Canada to be free from slavery.

David Nelson | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | September 24, 1793 Jonesborough, Tennessee, U.S. |

| Died | October 17, 1844 (aged 51) Quincy, Illinois, U.S. |

| Education | Washington College, Tennessee College of Physicians of Philadelphia |

| Organization(s) | Presbyterian Church Marion College American Anti-Slavery Society Mission Institute Underground Railroad |

| Known for | Founder of two colleges Fugitive in Marion County Lyrics to "The Shining Shore" The Cause and Cure of Infidelity Mentor to Elijah Lovejoy |

| Spouse | Amanda Frances Deaderick (m. 1822) |

| Children | Survived by 11 children |

Nelson was the author of The Cause and Cure of Infidelity, which includes an account of his conversion to Christianity. He also wrote the lyrics to "The Shining Shore," a popular hymn by composer George Frederick Root. Nelson is said to have written the poem while he was a fugitive in Marion County, Missouri, looking across the Mississippi River toward Quincy, Illinois.

Education and early career

editNelson was born near Jonesborough in East Tennessee in 1793.[1] His parents were originally from Rockbridge County, Virginia.[1] His father, Henry Nelson, was an elder in the Presbyterian Church.[1] His mother, Anna Kelsey Nelson, was a teacher.[2] Both taught at Washington College, which had been founded by Samuel Doak, a slaveowner who later became an abolitionist.[2] David attended Washington College, and graduated in 1809 at the age of sixteen.[1][3]

Medical training and practice

editNelson first studied medicine in Danville, Kentucky, under Ephraim McDowell, a pioneer surgeon.[1] He then went to the College of Physicians of Philadelphia, where he received his degree in 1812.[5] At the age of nineteen, he returned to Kentucky intending to practice medicine.[5] With the outbreak of the War of 1812, he joined a regiment in Kentucky instead, and went to Canada as a military surgeon.[1]

After the war, he returned to Jonesborough, Tennessee, where he had grown up.[5] Nelson opened a medical practice earning three thousand dollars a year.[3] On May 15, 1816, he married Amanda Frances Deaderick, the daughter of David Deaderick, a respected merchant.[2][1] They eloped because her father did not approve of Dr. Nelson, who had a reputation as an avid card player and gambler.[2]

Around this time, Elihu Embree and Benjamin Lundy were publishing antislavery newspapers in Jonesborough.[5] However, Nelson kept slaves during his years in Tennessee and Kentucky, and first adopted his antislavery views much later in Missouri.[5]

Entry into ministry

editAlthough Nelson had spent several years questioning his faith,[1] he had a change of heart and started studying theology privately with Reverend Robert Glenn.[2] He was reportedly inspired by missionary Elias Cornelius of the American Board of Commissioners for Foreign Missions, who gave a sermon when he passed through Tennessee.[3] In April 1825, Nelson was licensed to preach by the Abingdon Presbytery in Virginia,[1] and six months later, he was ordained as a minister `in Rogersville, Tennessee.[2] For two years, Nelson preached in East Tennessee, and traveled with Frederick Augustus Ross through Ohio, Tennessee, and Kentucky, as guest preachers in churches and revival meetings.[2] Nelson also collaborated with Ross and James Gallaher on editing the Calvinistic Magazine.[5][2]

In 1828, David Nelson became pastor of the Presbyterian Church in Danville, Kentucky, succeeding his brother Samuel who had died.[1] He also traveled extensively within Kentucky as an agent of the American Education Society,[1] and taught classes on medicine.[2] Reverend Nelson developed a reputation as a skilled orator and preacher who could "surprise and thrill...with eloquence and pathos."[5] Standing six feet two inches tall, with a large chest, he also had a powerful singing voice which he used effectively during worship.[3]

Founding of Marion College

editIn 1830, the Reverend Dr. David Nelson moved to Missouri and settled in what is now Union Township, 13 miles northwest of Palmyra, in Marion County.[5][6] He was sent to northeastern Missouri by the American Home Missionary Society (AHMS), along with several other Presbyterian ministers from Kentucky.[7]

Nelson soon had the idea of establishing a Protestant college to educate "industrious young men, farmers and mechanics."[6] He received financial backing from two partners who were large landowners in the area: Dr. David Clark, the first physician to settle in Marion County, and William Muldrow, a progressive farmer and speculator.[6] Muldrow was heavily involved in the early years of Marion College, and would later develop a reputation as a "visionary, fool, swindler."[8][9] The three founders envisioned a manual labor college that would eventually be self-supporting.[6] Students would be expected to farm the land for three hours a day.[6] Within a few years, they decided to add a theological seminary, in addition to a preparatory school and literary department.[6]

In 1830, Nelson and his co-founders submitted their proposal to establish Marion College to the legislature of Missouri. On January 15, 1831, Marion College became the first institution of higher learning to be chartered in the state.[6] Marion College was also granted the right to confer college and university degrees.[6] The founders received eleven acres of land, where they built their first school building, a log cabin.[6] In 1832, Dr. Nelson became the first president of Marion College, as well as its first teacher.[6][10]

Nelson traveled around the state to raise money for the school.[6] The education board of the Presbyterian Church pledged $10,000 to purchase more land for Marion College, but there were misunderstandings, and the agreement was dissolved.[6] In April 1833, Muldrow, Nelson and Clark secured a $20,000 loan from a bank in New York City,[6] to purchase 4,000 acres of land.[10] In the fall and winter of 1834, the three founders canvassed their contacts in the East and returned with $19,000 in donations and subscriptions.[6]

As of the winter of 1834, Marion College consisted of a one-story building and several cottages.[6] The Palmyra Courier, a Jacksonian newspaper which opposed the college, estimated that there were only 20 to 30 students.[6] Meanwhile, The Christian Almanac, which was supportive of the school, estimated that there were as many as 60.[6] In the summer of 1835, the construction of several new buildings was underway at multiple sites.[6] By the fall of 1835, the college catalog listed a total of 80 students, 52 of whom were from other states including New York, Pennsylvania, Ohio and Virginia.[6]

In 1835, Dr. Nelson resigned as president of Marion College,[11] although he remained on the board of trustees that year.[6] The exact circumstances are unknown, but his resignation was probably intended to appease proslavery groups in northeastern Missouri.[6] Nelson was succeeded by Presbyterian minister Reverend William S. Potts as president of Marion College.[6] Marion College encountered financial problems between 1837 and 1840,[9] and its final term started in May 1843.[6] By 1844, Marion College had closed.[6]

Abolitionism in Missouri

editIn early 1832, the First Presbyterian Church in St. Louis held a major revival meeting.[10] Reverend William S. Potts invited Reverend David Nelson to speak,[12] and succeeded in recruiting 126 new members that year.[10] Among the new members Nelson helped to recruit was Elijah Parish Lovejoy, who joined the church on February 9, 1832[10] and decided to enter the ministry.[12]

Around this time, abolitionist Theodore Weld was in St. Louis, possibly in early March.[10] Reverend Dr. David Nelson was converted to the antislavery cause after hearing one of Weld's lectures.[5] According to Reverend Asa Turner, Nelson declared, "I will live on roast potatoes and salt before I will hold slaves."[3]

Nelson himself is said to have been a major influence on Elijah Lovejoy both as a Presbyterian and as an antislavery activist.[12] Nelson later wrote about the teachings of Charles Finney and the Second Great Awakening and their implications for slavery in the St. Louis Observer, the evangelical newspaper run by Lovejoy.[7]

In the summer of 1835, Nelson attended the General Assembly of the Presbyterian Church in Pittsburgh, and heard Theodore Weld speak once again.[10] On June 16, 1835, the American Anti-Slavery Society voted to recommend the appointment of David Nelson as one of its agents.[10] Another abolitionist professor from Marion College, Job Halsey, was also appointed.[10] As one of 70 trained agents of the American Anti-Slavery Society (AASS), Nelson recruited white and black antislavery activists in Marion County.[7] He and his followers started Sunday schools to teach African Americans to read the Bible and also distributed antislavery literature, angering many in the local community.[7][2]

Tensions in Marion County

editIn 1836, there was a large influx of migrants from Pennsylvania, Ohio and other Eastern states to Marion County known as the "Eastern run".[13] Many of these newcomers opposed slavery.[10] Their arrival was viewed with mistrust and suspicion by local residents who were proslavery, and regarded them all as "abolitionists".[13]

Among the new migrants from the East were two men named Garrett and Williams, agents of the American Colonization Society, who had settled in Philadelphia, Missouri.[13] At Hannibal, it was discovered that Garrett and Williams had been bringing hundreds of tracts and pamphlets supporting colonization – the idea that slaves should be emancipated and sent to Africa – into Marion County.[13] A group of armed and mounted men led by Captain Uriel Wright organized at Palmyra and marched up to Philadelphia, took Garrett and Williams prisoner, searched the premises, and found a box of ACS pamphlets in an outbuilding, hidden under corn husks.[13] On their way back to Palmyra, the proslavery mob threatened to hang Garrett and Williams unless they left Missouri for good.[6][13] The mob took the box of ACS pamphlets to Palmyra. In front of a large, enthusiastic crowd there, they burned the pamphlets "formally and with some ceremony."[13]

That same day, a group rode to Dr. Nelson's house and surrounded it, demanding that he turn over any antislavery pamphlets as well.[5] Nelson warned them to leave. The mob left, threatening to come back for him.[5]

The Garrett-Williams incident was followed by a series of public meetings in Marion County denouncing anyone suspected of harboring sentiments opposing slavery, with many local citizens vowing to drive them out.[13] On May 21, 1836, Professor Ezra Stiles Ely was called before a meeting discussing the role of Marion College in the abolition movement.[10] Much to the alarm of abolitionist groups in the East, Ely admitted that he opposed slavery but denied supporting abolitionism and claimed to own a slave.[10] Garrett and Williams left for Illinois and later became students of David Nelson in Quincy.[2]

Life as a fugitive

editOn May 22, 1836, David Nelson was forced to flee for Illinois, after violence erupted in Marion County.[13] Reverend Nelson had been asked to give the Sunday sermon on the campground of his church in Union Township, a few miles from Marion College.[5][13] After his sermon, William Muldrow handed him a paper to read.[13] It was a plea for donations to help free slaves and send them to Liberia.[13] Nelson objected at first, telling Muldrow that he thought it would incite the proslavery mob once again.[5] Muldrow reassured him, and Nelson read the paper from the colonizationists.[5]

Stabbing of Dr. John Bosely

editDr. John Bosely, a slaveowner and a member of the congregation, was angered that Nelson had raised the slavery issue from the pulpit and rushed toward Nelson brandishing a cane.[5] Muldrow rushed toward Bosely to stop him, explaining that he was the one who had insisted that the colonizationist paper be read by Nelson.[5] A fight broke out, during which Bosely drew a spear and then a pistol, which he aimed at Muldrow and "snapped" twice.[13][5] In response, Muldrow drew his pocketknife and stabbed Bosely "under the left shoulder and into the left lung".[2][5][13] According to David Nelson's son, Dr. William Nelson, "Several men tied red handkerchiefs around their waists, got on their horses and started to raise a mob. Father started for home, but mother, who was frantic, persuaded him to start for Quincy."[5]

Escape to Illinois

editFor the next three days, Nelson hid and traveled by night until he reached the bank of the Mississippi River.[5] Along the way, he evaded many vigilantes with red handkerchiefs.[5] Meanwhile, two of his friends headed south to Hannibal, where they crossed the river by ferry and relayed a message to his contacts in Quincy, Illinois.[2] According to popular lore, Nelson was inspired to write his most famous poem, "The Shining Shore", while hiding near the riverbank, waiting to make his escape.[5][14]

At dusk, two church members from Quincy pretended to go fishing and followed signs until Nelson finally emerged from hiding.[5] On the boat, they fed him dried codfish and crackers, which led the starving Nelson to joke that he was turning into a "Yankee."[5] Nelson then went to stay at the old Log Cabin Hotel in Quincy, where rumors circulated that Nelson himself had stabbed Bosely.[5] The next day, a group of citizens from Quincy and from Missouri went to the hotel to protest Nelson's arrival, and demanded that he be placed in their custody.[5] Nelson refused to leave on the grounds that the men had no legal papers.[5] John Wood, the founder of Quincy who would later serve as governor, went to the hotel with 30 armed men to confront and break up the mob.[15]

Back in Missouri, William Muldrow was taken into custody, but was later defended by lawyer Edward Bates, and acquitted.[13] Dr. John Bosely recovered from his wounds.[5] David Nelson arranged for Amanda and their many children to wait at a friend's house in Missouri, where he arrived by night to take them back to Quincy.[2]

Once they were settled in Quincy, Nelson sent an open letter "To the Presbyterians of Missouri, who hold slaves," published in Elijah Lovejoy's newspaper, the St. Louis Observer.[2] The letter challenged slaveowners to reexamine their moral convictions.[2] In the years that followed, Nelson would avoid public appearances in Missouri as much as possible due to ongoing opposition to his presence, even declining an invitation to preach at his old church in Marion County.[5]

Opposition in Adams County

editOn June 10, 1836, a public meeting was called for citizens of Adams County, Illinois, to oppose the introduction of abolitionist societies and any discussion of abolitionism from the church pulpit. In the days leading up to the event, another minister, Reverend Asa Turner, warned church authorities and prepared for possible mob violence by placing loaded guns underneath the platform of his church pulpit. Turner proceeded to give a controversial sermon in which he denounced mob violence and slavery, in solidarity with Nelson.[5]

Both Nelson and Turner then become targets to be "removed" from Quincy. On Saturday, June 18, a large crowd gathered in Quincy, coming from all over Adams County. Joseph T. Holmes, acting as justice of the peace, went to the group leaders and warned them that if they formed a mob, he would read them the riot act and use force if necessary. After passing a resolution against abolition and getting drunk, the proslavery gathering dispersed without causing a major incident.[5]

Mission Institute and the Underground Railroad

editDavid Nelson was involved in setting up the Quincy chapter of the American Anti-Slavery Society (AASS) in 1836, and played a leading role in founding the Illinois Anti-Slavery Society (IASS) in 1837.[7] The Illinois Anti-Slavery Society held a convention in Alton, Illinois, from October 26 to 28, which Nelson attended together with his adult son, David D. Nelson.[7][2] The convention was called in support of Elijah Lovejoy, who had moved his antislavery newspaper from St. Louis to Alton, and continued to be harassed by mob violence.[7] Lovejoy himself would be killed less than two weeks later, becoming the first white martyr of the antislavery movement.[7]

As an AASS agent in the slave state of Missouri, Reverend Nelson had focused his efforts on helping slaveholders understand that slavery was a "sin."[7] Once he settled in the free state of Illinois, he shifted his focus to helping enslaved African Americans attain their freedom.[7]

In 1838, Nelson founded an abolitionist college known as the Mission Institute. In the years that followed, he helped to establish Quincy as a major point of entry to the Underground Railroad.[5] His presence in Quincy was said to have forced local citizens to "choose sides" in the slavery debate,[16] inspiring many "passive" opponents of slavery to take action.[7] Their proximity to Missouri also meant that local residents were exposed to the brutality of slaveowners, who ran ads in the Quincy Herald and came to Adams County to hunt down fugitive slaves, using force.[7] As a result of the efforts of Nelson and others, Adams County had more white residents who were known participants in the Underground Railroad than any other county in the state of Illinois.[7]

Founding of the Mission Institute

editOn October 30, 1838, Dr. and Mrs. Nelson gave 80 acres of land in trust for a new college, the Mission Institute, in Melrose Township near Quincy.[5] This became known as Mission Institute Number One, the first of four sites.[15] Number One included a chapel or meeting house and twenty log cabins built by students.[7][15] In 1840, Nelson established Mission Institute Number Two on an 11-acre site, which eventually included a two-story brick school and 20 to 30 cabins.[15]

The Mission Institute focused on educating young people for mission work in other countries. Graduates of the Mission Institute went on to serve as evangelical missionaries in New Zealand, Madeira and Africa.[5] Others became missionaries in North America, working in Oregon Territory, in Iowa Territory among the Winnebago Indians, and in Canada among fugitives from slavery.[17]

As enrollment increased, the Mission Institute received additional land grants from supporters in Quincy.[7] Nelson took on a partner, an abolitionist theologian named Moses Hunter from Allegany, New York, and tasked him with starting a women's department.[7] Although the Mission Institute Number One and Number Two were Presbyterian, Hunter was put in charge of Mission Institute Number Four, also known as "Theopolis," which was Congregationalist and focused on theological study.[7]

The school itself was later regarded as a failure,[5] but the Mission Institute played an important role in the Underground Railroad.[15] The trustees, teachers and students of the Mission Institute were all "unreservedly antislavery," which made it unpopular with local residents.[17] Nelson sent students and graduates of the Mission Institute to northeastern Missouri to preach the "whole gospel" to African Americans – enslaved and free – and help many slaves escape to freedom.[7]

Underground Railroad in Quincy

editThe Underground Railroad had been operating in Quincy from as early as 1830.[17] As a result of Nelson's efforts, Mission Institute Number One became the best known Underground Railroad station in Quincy.[18][15] The Nelson home called "Oakland" was nearby, with a built-in hiding place for fugitives.[15] Mission Institute Number Two, originally a four-room dormitory, also became a significant Underground Railroad station.[15]

Quincy itself became an important entrance point to the Underground Railroad in Illinois, along with Chester and Alton.[5] The Underground Railroad route originating in Quincy followed a route very similar to the later Chicago, Burlington and Quincy Railroad line.[5]

On March 9, 1843, proslavery arsonists set fire to the Mission Institute Number Two in Illinois.[5][15] According to historians, the Mission Institute had soon become "the special object of hatred by the slaveholders of Missouri,"[16] who referred to it as "Nelson College"[5] or the "abolitionist factory."[7] The Mission Institute buildings were burned down by a band of men from Palmyra, Missouri, who crossed over the "ice bridge" that had formed over the Mississippi River.[5] No attempts were made to arrest anyone. The arson was viewed by many as "fair retaliation" for the large number of slaves who had been "spirited away" from Marion County to freedom via Quincy, Illinois.[5] David Nelson started rebuilding the Mission Institute after it was burned down.[15]

Death and legacy

editDavid Nelson died on October 17, 1844, in Quincy, Illinois, at the age of 51.[1] He had been suffering from epilepsy.[1] His partner at the Mission Institute, Moses Hunter, died a few months later.[5][7] With the loss of both its leaders, it became clear that the Mission Institute could not survive.[7] In February 1845, the Mission Institute buildings were taken over by the Adelphia Theological Seminary.[7] In the years that followed, the frequent clashes between antislavery and proslavery factions in Adams County and Marion County seemed to subside.[5] Nelson is buried at Woodland Cemetery in Quincy, where there is a marble monument in his memory, erected by his friends from New York.[1]

"The Shining Shore"

editA decade after his death, composer George Frederick Root set David Nelson's poem "The Shining Shore" to music.[14] His mother had found the poem in a religious newspaper and passed it on to him.[14] Root only discovered much later that Nelson had written the words.[14] "The Shining Shore" became very popular during the American Civil War, and is quoted in the book Specimen Days by Walt Whitman.[2] In 1907, The Dictionary of Hymnology noted that the hymn, also known as "My days are gliding swiftly by", was "exceedingly popular".[19] More recently, classical music recording artists Anonymous 4 performed "The Shining Shore" on their album Gloryland, which debuted at #3 on the Billboard Classical Music chart in 2006.[2][20]

Discovery of secret room at Oakland

editIn the 1960s, Ruth Deters's family discovered a hidden room underneath a trap door in their home, east of Quincy, Illinois, after one of her young sons hid from a babysitter.[2] Although she and her husband had known that Dr. Nelson had built the house, they had been unaware that "Oakland" had been an Underground station in its own right, with a secret room and tunnel which once led out of their basement.[2] Deters then embarked on several decades of research, culminating in her 2008 book, The Underground Railroad Ran Through My House![2] The book investigates over 32 Underground Railroad stations in Quincy, in addition to the Mission Institute sites.[15]

Written works by David Nelson

editBooks

edit- The Cause and Cure of Infidelity: A Notice of the Author's Unbelief and the Means of His Rescue[21]

- An Appeal to the Church in Behalf of a Dying Race: From the Mission Institute Near Quincy, Illinois[22]

- Dr. Nelson's Lecture on Slavery[23]

Hymns

editReferences

edit- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n Sprague, William B. (1858). "David Nelson, M.D.". Annals of the American Pulpit (PDF). Vol. 4. New York: Robert Carter & Brothers. pp. 677–680. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2019-09-23. Retrieved 2022-03-04 – via Wikimedia Commons.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v Deters, Ruth (2008). The Underground Railroad Ran Through My House! How the intriguing story of Dr. David Nelson's home uncovered a region of secrets. Quincy, Illinois: Eleven Oaks Publishing. pp. 3–13, 23, 28, 29–32, 41, 47, 52–53, 57, 72, 139, 141–142. ISBN 978-0-578-00213-2.

- ^ a b c d e Magoun, George F. (1889). Asa Turner: A Home Missionary Patriarch and his Times. Boston and Chicago: Sunday School Publishing Society. pp. 146–147 – via Internet Archive.

- ^ Deters, Ruth (2008). The Underground Railroad Ran Through My House!. pp. 25–26.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab ac ad ae af ag ah ai aj ak al am an ao ap aq ar Richardson, Jr., William (January 1921). "Dr. David Nelson and His Times". Journal of the Illinois State Historical Society. 13 (4): 433–463. JSTOR 40186795. Archived from the original on 2022-02-14. Retrieved 2022-02-14 – via JSTOR.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y McKee, Howard I. (April 1942). "The Marion College Episode in Northeast Missouri History". Missouri Historical Review. 36 (3): 299–319 – via Digital Collections – The State Historical Society of Missouri.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v Prinsloo, Oleta (Spring 2012). "'The Abolitionist Factory:' Northeastern Religion, David Nelson, and the Mission Institute near Quincy, Illinois, 1836–1844". Journal of the Illinois State Historical Society. 1–5 (1): 36–68. doi:10.5406/jillistathistsoc.105.1.0036. JSTOR 10.5406/jillistathistsoc.105.1.0036. Archived from the original on 2022-02-20. Retrieved 2022-02-20 – via JSTOR.

- ^ Livingston, Dewey (September 16, 2020). "Muldrow City: Dreams with No Foundation". Marin County Free Library. Archived from the original on 2022-02-15. Retrieved 2022-02-15.

- ^ a b Sampson, F. A. (July 1926). "Marion College and Its Founders". Missouri Historical Review. 20 (4): 485, 487. Archived from the original on 2022-02-15. Retrieved 2022-02-15 – via State Historical Society of Missouri.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Merkel, Benjamin G. (April 1950). "The Abolition Aspects of Missouri's Anti-Slavery Controversy 1819–1865". Missouri Historical Review. 44 (3): 232–253. Archived from the original on 2022-03-05. Retrieved 2022-03-04 – via State Historical Society of Missouri.

- ^ Bob Piddy (1982). Across Our Wide Missouri: Volume I, January through June. Independence, MO: Independence Press. pp. 40–41.

- ^ a b c Van Ravenswaay, Charles (1991). St. Louis: An Informal History of the City and Its People, 1764–1865. Missouri Historical Society Press. pp. 277, 280. ISBN 978-0-252-01915-9. Archived from the original on 2022-03-05. Retrieved 2022-02-13.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o Holcombe, Return Ira (1884). History of Marion County, Missouri. St. Louis: E. F. Perkins. pp. 217–219. Archived from the original on 2022-02-17. Retrieved 2022-02-17 – via Missouri Digital Heritage.

- ^ a b c d e Root, George Frederick (1891). Story of a Musical Life: An Autobiography. Cincinnati: John Church Co. pp. 99–100, 256.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k "Historic Quincy Illinois: Gateway, 1835–1865" (PDF). See Quincy. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2021-07-30. Retrieved 2022-02-19.

- ^ a b Gara, Larry (Autumn 1963). "The Underground Railroad in Illinois". Journal of the Illinois State Historical Society. 56 (3): 510. JSTOR 40190624. Archived from the original on 2022-02-20. Retrieved 2022-02-20.

- ^ a b c Kilby, Clyde S. (Autumn 1959). "Three Antislavery Prisoners". Journal of the Illinois State Historical Society. 52 (3): 419–430. JSTOR 40189680. Archived from the original on 2022-02-20. Retrieved 2022-02-20.

- ^ "Quincy's History". Quincy Area Chamber of Commerce. Archived from the original on 2022-02-20. Retrieved 2022-02-21.

- ^ "David Nelson". Hymnary.org. Archived from the original on 2022-02-20. Retrieved 2022-03-04.

- ^ Westphal, Matthew (September 22, 2006). "Anonymous 4's Gloryland Lands on Billboard Classical Chart at No. 3". Playbill. Archived from the original on 2022-03-05. Retrieved 2022-03-04.

- ^ Nelson, David (1850). "The Cause and Cure of Infidelity". Library of Congress. Archived from the original on 2022-02-20. Retrieved 2022-02-20.

- ^ Nelson, David. An appeal to the church in behalf of a dying race. OCLC 765806285. Archived from the original on 2022-02-20. Retrieved 2022-02-20 – via WorldCat.

- ^ Nelson, David. Dr. Nelson's Lecture on Slavery. OCLC 607356921. Archived from the original on 2022-03-05. Retrieved 2022-02-20 – via WorldCat.

- ^ "My days are gliding swiftly by". Hymnary.org. Archived from the original on 2022-02-20. Retrieved 2022-02-20.

- ^ "This world explore, from shore to shore". Hymnary.org. Archived from the original on 2022-02-20. Retrieved 2022-02-20.

- ^ "'Twas told me in my early day". Hymnary.org. Archived from the original on 2022-02-20. Retrieved 2022-02-20.

- ^ "O Lord, be thou with those who sail". Hymnary.org. Archived from the original on 2022-02-20. Retrieved 2022-02-20.

Further reading

edit- Deters, Ruth (2008). The Underground Railroad Ran Through My House! How the intriguing story of Dr. David Nelson's home uncovered a region of secrets. Quincy, Illinois: Eleven Oaks Publishing. ISBN 978-0-578-00213-2.

- Richardson, Jr., William (January 1921). "Dr. David Nelson and His Times". Journal of the Illinois State Historical Society. 13 (4): 433–463. JSTOR 40186795 – via JSTOR.

External links

edit- The Rev. Dr. David Nelson Arrives in Quincy (Historical Society of Quincy & Adams County)

- Map of Quincy; Dr. David Nelson Home and Mission Institute (Illinois Digital Archives)