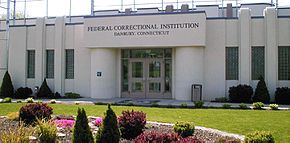

The Federal Correctional Institution, Danbury (FCI Danbury) is a low-security United States federal prison for male and female inmates in Danbury, Connecticut. It is operated by the Federal Bureau of Prisons, a division of the United States Department of Justice. The facility also has an adjacent satellite prison camp that houses minimum-security female offenders.

| |

| |

| Location | Danbury, Fairfield County, Connecticut |

|---|---|

| Status | Operational |

| Security class | Low-security (with minimum-security prison camp) |

| Population | 793 (46 in prison camp) |

| Opened | 1940 |

| Managed by | Federal Bureau of Prisons |

History

editFCI Danbury was opened in August 1940 with the purpose of housing male and female inmates.[1] It housed several high-profile prisoners during World War II. Conscientious objectors, including poet Robert Lowell and civil rights activist James Peck, were housed there for refusing to enter the military draft in the early 1940s.[2][3][4] Robert Henry Best served most of his life sentence at FCI Danbury after being convicted of treason in 1948 for making propaganda broadcasts for the Nazis during the war. Screenwriter Ring Lardner Jr., a member of the Hollywood 10, a group of filmmakers who were charged with contempt of Congress in 1947 for refusing to answer questions regarding their alleged connections with the Communist Party USA, served nine months there.[5]

Beginning in the 1970s, Yale Law School began providing legal services for prisoners at FCI Danbury.[6] As of the 2010s, Yale students and professors still regularly visit the facility.[7]

FCI Danbury became exclusively for female inmates in 1993.[8] This was because there was a lack of space for women in the Northeastern United States and due to the growth in the number of female prisoners.[9]

In August 2013, the Federal Bureau of Prisons announced that FCI Danbury was going to be reverted to an all-male facility to alleviate overcrowding across the entire federal prison system. The female inmate population will be transferred to the Federal Correctional Institution, Aliceville in Alabama, which opened in 2013 and has over 1,500 low-security beds for female inmates. It was estimated that the change would be completed by December 2013.[10][11][12] However, female inmates were not transferred to other facilities until April 2014.

FCI Danbury and its camp were the only federal prisons in the Northeast which housed women, and the repurposing would further promote an imbalance of women's prisoner space within the BOP system.[7] In August 2013, 11 senators from the Northeast sent a letter to the BOP director criticizing the move, since it would mean there would be no facility for female federal prisoners from the Northeast; the move would mean that all of the women would be far from their families and loved ones. In November of that year several senators announced that at FCI Danbury the BOP would install a new low security camp for women and convert an existing minimum security camp into a low security camp for women to remedy the issue.[6] As of August 2014 there was no timeline for the installation of the new women's facilities,[13] no new construction had yet occurred at FCI Danbury. U.S. citizens would be eligible for the camps, but non-U.S. citizens would still be incarcerated farther away.[6] As of that time there were no federal women's prisons left in the Northeast.[7] Orange Is the New Black: My Year in a Women's Prison writer Piper Kerman criticized the move in an op-ed in The New York Times.[14] A new $25 million women's facility was completed and began accepting female inmates in December 2016.[15]

In July 2024, former White House chief strategist Steve Bannon began serving a four month prison sentence at the facility for a contempt of Congress conviction.[16]

Location and facilities

editFCI Danbury is located in southwestern Connecticut, approximately 55 miles (89 km) from New York City,[17] 60 miles (97 km) from Hartford, Connecticut, and 150 miles (240 km) from Boston, Massachusetts.[9]

The facility is accessible to a MetroNorth station fewer than 4 miles (6.4 km) from the facility. Four Amtrak stations are within 30 miles (48 km) from the facility.[9]

The prison had at one point included athletic facilities such as a running track, a soccer field, handball courts, a baseball diamond, and a handball field, since there is a large amount of outdoor area in the FCI Danbury property.[9]

Programs

editPrior to the facility's conversion it offered General Education Development (GED) programs, paralegal classes, a group therapy program for people with post-traumatic stress disorder called the "Bridge Program", and a residential drug abuse program. The prison chaplain, religious groups, and volunteer groups had offered educational and other programming. In addition, prior to 1999 the prison hosted a "children's day" so inmates could spend time with their children.[9]

Notable incidents

editDeadly 1977 fire

editOn July 7, 1977, at about 1:15 am, a fire began in an inmate's clothes hanging on wooden pegs in one of the prison washrooms, and before it was extinguished about 45 minutes later, five inmates had died of smoke inhalation. The most significant factors contributing to the deadly fire were the presence of fuels that promoted rapid flame and smoke development, the failure to evacuate occupants quickly and reliably (the two primary exits were blocked by the fire and a broken key in a lock, leaving a narrow catwalk as the only exit), and the fire not being extinguished in an incipient stage. An automatic sprinkler system would have been the most reliable fire defense; however, even without automatic detection and suppression equipment, the fire safety system, with little expenditure of money, could have been more effective by revisions to emergency procedures in the fire plan. The Danbury Fire Department was not called until about 15 minutes after the fire's discovery because of a fire plan that called for initial use of the institution's firefighting resources, but the inmate fire brigade was never released from housing units and the institution's fire apparatus was never used. The ensuing public outcry led to several investigations and reviews of the prison's fire safety systems and protocols. A comprehensive program of fuel control, additional fire detection and suppression equipment, and training and planning sessions have also been established, not only at FCI Danbury but throughout the rest of the federal prison system.[18][19]

Correction Officer Michael Rudkin

editIn 2008, supervisory staff at FCI Danbury discovered that Correction Officer Michael Rudkin had been having consensual sexual relations with a female inmate. When questioned, Rudkin, who was married at the time, admitted to the affair and stated that it had been going on for approximately one year. An FBI and United States Department of Justice Office of the Inspector General (OIG) [20] investigation revealed that Rudkin had sexual encounters with other inmates as well. Since it is illegal for prison staff to have sexual relations with inmates under their care regardless of consent, Rudkin pleaded guilty to sexual abuse of a ward and was sentenced to prison at the United States Penitentiary, Coleman, a high-security facility in Florida.

Rudkin was subsequently convicted in 2010 of attempting to hire a hitman to kill his former inmate paramour, his ex-wife, his ex-wife's new boyfriend, and an OIG special agent assigned to his case while at USP Coleman.[21] He was sentenced to 90 years in federal prison.[22] Rudkin was severely beaten at the United States Penitentiary, Terre Haute on August 23, 2021 and died the following day at the age of 56.[23]

In popular culture

editThe fictional Litchfield Prison in Upstate New York in the Netflix original television series Orange Is the New Black is based in part on FCI Danbury, where Piper Kerman, who wrote the memoir on which the series is based, was incarcerated in 2004 and 2005 after her conviction for money laundering and drug trafficking.[24]

George Jung served a sentence at FCI Danbury. His incarceration was portrayed in the 2001 film Blow starring Johnny Depp.[25]

The Weeds character Nancy Botwin serves time at FCI Danbury.[26]

The Suits character Mike Ross begins Season 6 of the television show in FCI Danbury.[27]

Gina Zanetakos of The Blacklist was incarcerated at FCI Danbury before she escaped.

In the 1995 movie The American President, Presidential Assistant Lewis Rothschild (played by Michael J. Fox) says "Say what you want. It's always the guy in my job that ends up doing 18 months in Danbury minimum security prison."

In season 6 of The Sopranos, the character John "Johnny Sacks" Sacramoni, the head of the New York mafia family (played by Vincent Curatola), was incarcerated at FCI Danbury.

In the 2023 series White House Plumbers, G. Gordon Liddy (played by Justin Theroux) is promised he’ll serve the prison sentence for his role in the Watergate break-ins at FCI Danbury.

Notable inmates

edit| Inmate name | Register number | Photo | Status | Details |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Steve Bannon | 05635-509 | Turned himself in on Monday, 1st July, 2024. Scheduled for release October 29, 2024.[28] | Bannon was a key adviser to Trump's 2016 presidential campaign, then served as his chief White House strategist during 2017. Bannon is not the first former top official from Trump's White House to go to prison. Peter Navarro, a former Trump trade adviser, went to prison after being given a four-month sentence. President Trump in 2021 pardoned Bannon on federal criminal charges accusing him of swindling Trump supporters involving an effort to raise private funds to build a wall on the Mexico–United States border.[28] | |

| Leona Helmsley | 15113-054 | Released from custody in 1994; served 21 months.[29] | Upscale hotel owner and leading real estate investor in New York City; convicted of tax evasion in 1989 for failing to pay $1.7 million in taxes from 1983 to 1985; known as the "Queen of Mean" for her tyrannical management style.[30] | |

| Sun Myung Moon | 03835-054 | Released from custody in 1985; served 11 months.[31] | Leader of the Unification Church; convicted of tax evasion in 1982; the United States v. Sun Myung Moon serves as a landmark case involving taxes and religious organizations.[32][33] | |

| Lauryn Hill | 64600-050 | Released from custody in 2013; served 3 months.[34] | Grammy Award–winning singer and actress; pleaded guilty in 2012 to not reporting over $2.3 million in income by intentionally failing to file tax returns for five years.[35][36] | |

| Piper Kerman | 11187-424 | Released from custody in 2005; served 13 months.[37] | Pleaded guilty to money laundering in 1998; authored Orange Is the New Black: My Year in a Women's Prison (2010), which chronicles her time at FCI Danbury; the Netflix television series Orange Is the New Black is based on Kerman's book.[38] | |

| Teresa Giudice | 65703-050 | Served a 15-month sentence; released on December 23, 2015, after serving 12 months.[39] | Star of the Bravo television show Real Housewives of New Jersey; she and her husband, Joe Giudice, pleaded guilty in 2014 to bankruptcy fraud and mail fraud for lying to banks and hiding assets in order to avoid paying taxes on $1 million; Joe Giudice received 41 months.[40][41] | |

| Alexander Salvagno | 11212-052 | Was serving a 17-year sentence; compassionately released on April 23, 2020. | Former owner of Evergreen Resources, a fertilizer manufacturer; convicted in 1999 of ordering employees to handle and dispose of cyanide waste without required safety measures; received the longest sentence ever imposed for an environmental crime.[42] | |

| Robert Lowell[26] | Served several months | Pulitzer Prize winner for Poetry in 1947, was a conscientious objector during World War II[43] | ||

| Sister Ardeth Platte[44] | 10857-039 | Imprisoned until December 22, 2005; served 29 months | Dominican nun and antiwar activist; convicted of breaking into and defacing a Colorado LGM-30 Minuteman missile silo.[45] | |

| Cheng Chui Ping | 05117-055 | Transferred to a facility in Texas, died in 2014 | Also known as Sister Ping. Ran a human smuggling operation from New York City and Hong Kong from 1984 until 2000, when she was arrested in Hong Kong, extradited back to the United States. | |

| Bob Jones | Released in January 1970. | Grand Dragon of the North Carolina Knights of the Ku Klux Klan; sentenced to a year in prison for contempt of Congress (refused to answer questions or provide records to the House Un-American Activities Committee as part of its investigation into Klan activity). | ||

| Ring Lardner Jr. | Served 9 months | An award-winning screenwriter sentenced to one year in prison in 1950 for contempt of Congress after appearing before the House Un-American Activities Committee in 1947 and refusing to answer questions about possible Communist affiliations. | ||

| James Peck | Released in 1945 after serving 3 years | An activist and conscientious objector who served a three-year stint in Danbury in the 1940s after refusing to serve in World War II. During his time in Danbury, Peck helped start a work strike that led to the desegregation of the prison's mess hall. | ||

| Michael Mancuso | 04640-748 | Sentenced to 15 years in 2008, released in 2019 after serving 153 months (12 years 9 months). | Mafia boss from New York, convicted of orchestrating the murder of a rival mafia member. | |

| Karl Sebastian Greenwood | 76231-054 | Serving a 20-year sentence; scheduled for release on November 15, 2035. | Co-founder of a massive fraud scheme called OneCoin. In September 2023, Greenwood was sentenced to a 20-year federal prison term (minus 5-years already served).[46] | |

| Caroline Ellison | 36854-510 | Serving a 2-year sentence; release date July 20, 2026. | Former CEO of Alameda Research and ex-girlfriend of Sam Bankman-Fried; pleaded guilty to fraud and other crimes in the FTX scandal. |

See also

editReferences

edit- Arons, Anna, Katherine Culver, Emma Kaufman, Jennifer Yun, Hope Metcalf, Megan Quattlebaum, and Judith Resnik. "Dislocation and Relocation: Women in the Federal Prison System and Repurposing FCI Danbury for Men". Yale Law School, Arthur Liman Public Interest Program. September 2014.

Notes

edit- ^ "Five Die in Danbury, Connecticut, Federal Correctional Institution Fire" (PDF). National Fire Protection Association. March 1978. Archived (PDF) from the original on February 7, 2016.

Fire Journal

- ^ "Poet Robert Lowell sentenced to prison". history.com.

- ^ "Robert Lowell's Letter to FDR". Dialog International.

- ^ Pace, Eric (July 13, 1993). "James Peck, 78, Union Organizer Who Promoted Civil Rights Causes". The New York Times.

- ^ Severo, Richard (November 2, 2000). "Ring Lardner Jr., Wry Screenwriter and Last of the Hollywood 10, Dies at 85". The New York Times.

- ^ a b c Arons, et al., p. 2.

- ^ a b c Arons, et al., p. 7.

- ^ "Danbury federal prison to switch to federal inmates". The Day. February 4, 1993.

- ^ a b c d e Arons, et al p. 8.

- ^ "Women Moved From Danbury Federal Prison As Institution Goes Male". Danbury Daily Voice. August 6, 2013. Retrieved October 21, 2013.

- ^ O'Malley, Denis (October 19, 2013). "Inmates on the move at federal prison in Danbury". The News-Times. Retrieved October 21, 2013.

- ^ "FCI Danbury". Federal Bureau of Prisons. Retrieved October 21, 2013.

- ^ Aron, et al., p 3.

- ^ Kerman, Piper. "For Women, a Second Sentence" (Archive). The New York Times. August 13, 2013. Retrieved on March 27, 2016.

- ^ Ryser, Bob (December 2, 2016). "Federal prison reopening to women". The News-Times.

- ^ Dempsey, Christina; Gagne, Michael (July 1, 2024). "Former Trump adviser Steve Bannon says he's 'proud' as he reports to Danbury prison". Retrieved July 1, 2024.

- ^ "FCI Danbury". Federal Bureau of Prisons.

- ^ "Danbury, Connecticut - Five Die in Federal Correctional Institution Fire (From Analyses of Three Multiple Fatality Penal Institution Fires, 1978)". National Fire Protection Association.

- ^ "The Danbury Prison Fire - What Happened? What Has Been Done To Prevent Recurrence?" (PDF). General Accounting Office.

- ^ https://oig.justice.gov/reports/press/2010/2010_04_28.pdf [bare URL PDF]

- ^ "Jury Finds Former Federal Correctional Officer, Now an Inmate, Guilty of Attempts to Kill Federal Agent and Informant". Federal Bureau of Investigation.

- ^ Hudak, Stephen (July 18, 2010). "Former federal corrections officer gets 90 years in prison for trying to arrange murders behind bars". Former federal corrections officer gets 90 years in prison for trying to arrange murders behind bars.

- ^ "AP sources: Jailed ex-officer in murder plot beaten to death at federal prison in Terre Haute". August 26, 2021.

- ^ Cooper, Anneliese. "'Orange Is the New Black's Prison Location Isn't Real, But It's Not Entirely Fictional Either". Bustle. June 6, 2014. Retrieved on March 27, 2016.

- ^ Graham, Renee (July 7, 1993). "Weymouth's Wayward Son". The Boston Globe. p. 49.

- ^ a b Barry, Doug. "Real-Life Sister Ingalls Even More Awesome Than She Is on OITNB". Jezebel. August 4, 2013. Retrieved on March 27, 2016.

- ^ "Patrick J. Adams tells of character's journey in new 'Suits' season. The Columbus Dispatch

- ^ a b Lynch, Sarah N. (July 1, 2024). "Trump ally Steve Bannon begins prison term for contempt". Thomson Reuters. reuters.com. Retrieved July 1, 2024.

… Bannon arrived at a low-security federal prison in Danbury, Connecticut, and spoke to reporters …

- ^ Bernstein, Adam (August 21, 2007). "Leona Helmsley, 87; ruthlessly ran part of hotel empire". Boston.com. Retrieved October 17, 2015.

- ^ Goldman, John J. (March 19, 1992). "Leona Helmsley Sentenced to 4 Years in Prison: Taxes: The hotel queen must surrender on April 15. Her plea to remain free to care for her ailing husband is rejected". Los Angeles Times.

- ^ "Moon to Be Released From Danbury Prison". The New York Times. July 3, 1985. Retrieved October 17, 2015.

- ^ "Moon Conviction Is Upheld by Court". The New York Times. September 14, 1983.

- ^ Blair, William G. (July 5, 1985). "Moon Released After 11 Months in a U.S. Prison". The New York Times.

- ^ Botelho, Greg (October 7, 2013). "Grammy-winning singer Lauryn Hill released from federal prison". Cable News Network. Retrieved October 17, 2015.

- ^ "Lauryn Hill starts prison sentence". USA Today. July 9, 2013.

- ^ USDOJ: US Attorney's Office - District of New Jersey. Justice.gov (May 6, 2013). Retrieved on 2013-10-23.

- ^ Garcia, Catherine (February 23, 2015). "Orange is the New Black's Piper Kerman opens up about the catharsis of prison memoirs". The Week. Dennis Publishing. Retrieved October 17, 2015.

- ^ Humphrey, Michael. "Ex-Convict Piper Kerman on Her Hot New Memoir, Orange Is the New Black". New York Media, LLC.

- ^ Takeda, Allison (April 1, 2015). "Teresa Giudice Prison Photo Reveals How Much She's Changed as She and Joe Open Up About Her Ordeal". Us Weekly. Victoria Lasdon Rose. Retrieved October 18, 2015.

- ^ Nolan, Caitlin; McShane, Larry (March 4, 2014). "Teresa Giudice, Joe Giudice plead guilty to fraud charges; both face prison, while he could be deported". New York Daily News. Retrieved July 17, 2015.

- ^ Strohm, Emily; Rayford-Rubenstein, Janine (October 2, 2014). "Teresa Giudice Sentenced to 15 Months in Prison on Fraud Charges". People. Retrieved July 17, 2015.

- ^ "Idaho Man Given Longest-Ever Sentence for Environmental Crime". US Department of Justice. April 29, 2000. Retrieved October 27, 2013.

- ^ "Army & Navy - Draft: Dodgers and Dissenters", Time, October 25, 1943, p.12.

- ^ Jamie Manson (June 10, 2015). "The nun and the actress behind 'Orange is the New Black'". National Catholic Reporter. Retrieved December 21, 2020.

- ^ Matt Apuzzo (December 22, 2005). "Nun Who Defaced Missile Silo Released from Prison". Archived from the original on July 14, 2014.

- ^ "Co-founder of fake cryptocurrency scheme sentenced to 20 years in US prison". Reuters. September 13, 2023. Retrieved September 3, 2024.

Further reading

edit- Rosepiler, Vicki. "Martha Just One of Us". The Progressive Populist. September 2004. - A letter to the editor from an FCI Danbury inmate