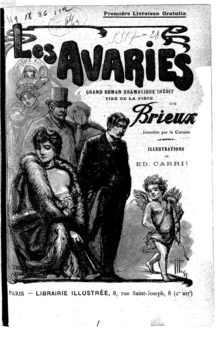

Les Avariés ([lɛ.z‿a.va.ʁje], "The Damaged Ones")[1] is a 1901 play written by French playwright Eugène Brieux.[2] Controversially, the play centred on the effect of syphilis on a marriage, at a time when sexually transmitted diseases were a taboo topic rarely openly discussed. For this reason, it was censored for some time in France and later in England.[3]

An English translation by John Pollock under the title Damaged Goods was published in 1911[4] and staged in the United States and Britain, including a run on Broadway in 1913 starring Richard Bennett.[5] It was later the subject of several film adaptations. The first, a 1914 silent film also starring Bennett, inspired a craze of subsequent "sex hygiene" films.

Brieux dedicated the play to Jean Alfred Fournier, Europe's leading syphilologist.[6]

Synopsis

editThe play is in three acts. It centers on George Dupont, age 26, who is engaged to be married.

In the first act, Dupont is informed by a doctor that he is infected with syphilis. The doctor urges Dupont to postpone his marriage until he has been cured of the infection. (At the time the play was written, this would have entailed three to four years of treatment with mercury-based compounds.) Dupont rejects the doctor's advice, and moves forward with the wedding.

The second act takes place some time later, with Dupont having married his fiancée, Henriette, who has recently given birth to their first child. Their newborn was found to be sickly, and was sent to the country to recuperate under the care of George's mother, Madame Dupont. Dupont brings the baby back to George's home because the baby's health has further deteriorated. A doctor (the same that diagnosed Dupont in the first act) arrives and advises that the wet nurse be relieved of her duty lest she contract an illness from the baby. Dupont objects, and offers the wet nurse a considerable sum of money to stay on, which she accepts.

After inspecting the baby, the doctor announces it is afflicted with congenital syphilis. He threatens to inform the wet nurse of this if the Duponts insist on retaining her service, but the nurse learns of the diagnosis from a butler and refuses to honor her previous agreement to feed the baby. The act ends with the arrival of Dupont's wife, Henriette, who overhears what has transpired and falls to the floor screaming.

The third act takes place in a hospital. Monsieur Loche, a politician and the father of Henriette, arrives at the hospital to confront the doctor who had initially diagnosed Dupont. Loche wishes to effect a divorce, and asks the doctor to sign a statement attesting to Dupont's syphilis diagnosis. The doctor declines, citing doctor-patient confidentiality. Loche despairs that there ought to be a law mandating medical examination before marriage. The doctor disagrees, complaining that "there are too many [laws] already". Instead, the doctor suggests a need for more education and open discussion of sexually transmitted diseases, and for an end to the stigmatization of syphilis as a "shameful disease":

Syphilis must cease to be treated like a mysterious evil, the very name of which cannot be pronounced...People ought to be taught that there is nothing immoral in the act that reproduces life by means of love. But for the benefit of our children we organize round about it a gigantic conspiracy of silence. A respectable man will take his son and daughter to one of these grand music halls, where they will hear things of the most loathsome description; but he won't let them hear a word spoken seriously on the subject of the great act of love. The mystery and humbug in which physical facts are enveloped ought to be swept away and young men be given some pride in the creative power with which each one of us is endowed.[7]

Themes

editEugène Brieux had been steadily producing morally didactic plays dealing with social problems since 1890.[8] Brieux identified "the problem of the position of Woman in modern society" as a leitmotif in his work, and stated a goal of "[awakening] society to the fact that Woman is mistreated and maltreated, and that as a weaker being she needs a helping hand to win a better position in life."[9] He identified Damaged Goods with this theme, along with several of his other plays, including Blanchette (1892) and La Femme Seule (1913).[9]

Damaged Goods was seen as a rebuke of the Victorian "double standard" of sexual morality, in which women were expected to remain chaste and monogamous, but it was tolerated for men to have sex with prostitutes (under the theory that men required an outlet for their sexual energies, and ought not inflict their "animal" passions on their wives).[5]: 32 The plight of George's wife and child is an example of what progressive physicians and sexual hygienists called "innocent infections" (or syphilis insontium). Whereas previously venereal disease had been seen as the deserved consequence of immoral behaviour, around the turn of the century there came a heightened awareness of how these diseases could be spread to "innocent" victims, particularly from husband to wife and unborn child.[5]

Composition and publication history

editBrieux wrote Les Avariés in 1901.[3]

John Pollock translated the play to English in 1905 under the title Damaged Goods. His translation was not published until May 1911 alongside two other translations in the book Three Plays By Brieux. The book sold well in the United States and England and went through multiple editions.[3] Irish playwright George Bernard Shaw wrote a preface to the book which included praise for Les Avariés:

No play ever written was more needed than Les Avariés...Sex is a necessary and healthy instinct; and its nurture and education is one of the most important uses of all art; and, for the present at all events, the chief use of the theatre.[2]

An English novelization, also titled Damaged Goods, was published by Upton Sinclair in 1913 with the approval of Brieux. The novelization closely follows the play and incorporates most of its dialogue.[3]

Production history

editBrieux was prevented from staging the play in Paris by censors, but was eventually granted permission to present a private reading at the Théâtre Antoine in 1902.[3]

Canada

editLes Avariés was staged at Montreal's Théâtre des Nouveautés in 1905, with the theatre taking the unusual measure of admitting only men. A critical notice in the newspaper Le Nationaliste declined to describe the play's subject matter, but offered the opinion that the play "despite the poor reputation which preceded it in Canada... posed not the slightest danger to a male audience"[a].[10]

United States

editThe first US productions of Damaged Goods were produced by the Sociological Fund, a fund created by the editors of the journal Medical Review of Reviews and led by Edward L. Bernays, who managed to raise $11,000 for the play.[5] The actor Richard Bennett played the lead role of George Dupont and also served as a producer and public face of the production.[3]

The first performance of Damaged Goods, a special matinee for members of the Sociological Fund, occurred on March 14, 1913, at the Fulton Theatre on Broadway. The following month, the Sociological Fund arranged for a special performance of the play on April 6 at the National Theatre in Washington DC for US President Woodrow Wilson, members of Wilson's cabinet, and members of Congress.[5][3]

The play had its public premiere on May 14, 1913, at the Fulton Theatre. It played for 66 performances, exceeding its initially planned run of 14 performances due to unexpected demand. Following its Broadway run, Bennett took the play on tour across the country, where its success continued.[3]

In the years following its Broadway debut, Damaged Goods was staged by a number of stock theatre companies across the United States. One of the earliest was a June 1914 production by William Fox's Academy of Music Stock Company in New York, which ran for six weeks of well-attended performances.[11]

Damaged Goods was briefly revived on Broadway at the 48th Street Theatre in May 1937 by Henry Herbert, who attempted to modernize the story. It was not well received by critics and played for only eight performances.[3]

England

editThe first performance of Damaged Goods in England occurred on February 16, 1914, at London's Little Theatre.[3] It was privately produced by the Authors' Producing Society and sponsored by the Society for Race Betterment.[12]

It was subsequently banned by British censors. The ban was lifted in 1916,[3] and a new production was staged in 1917 at St Martin's Theatre by J. B. Fagan.[4] It later toured around the country. In 1943, it was revived at Whitehall Theatre, having undergone some modernizing updates by Pollock.[4]

Australia

editA production of Damaged Goods was staged at Theatre Royal, Melbourne in December 1916. The play's subject matter reportedly led to a reaction of stunned silence from the audience after the final curtain fell on the show's premiere.[13]

Controversy

editTheatre historian Gerald Bordman has stated that Damaged Goods "unquestionably was one of the most powerful and most controversial dramas of its era".[14] The play's frank discussion of syphilis was shocking in its time, as sexually transmitted disease was considered a taboo topic. For example, the New York Times in its (positive) review of the 1913 Broadway production euphemistically referred to the play's subject matter as a "rare blood disease" and "a subject which hitherto has practically been confined to medical publications".[5] One of the few earlier plays to mention sexually transmitted disease was Henrik Ibsen's Ghosts (1881), which was similarly controversial,[15] though Damaged Goods was the first play staged in the United States to use the word "syphilis".[16] The American production of Damaged Goods mitigated the potentially controversial effect of its subject matter by its association with the respectable journal Medical Review of Reviews, as well as gaining the approval of John D. Rockefeller and the mayor of New York.[14] In a feature story, the New York Times described the play as having "the approval of many of our leading men and women".[17]

Film adaptations

editDamaged Goods was the subject of a number of film adaptations. The first, Damaged Goods (1914), was an American silent film in which Richard Bennett reprised the role of George Dupont which he played in the US stage production. It has been credited with sparking a fad of sensational "sexual hygiene" films (sometimes colloquially referred to as "clap operas"),[18] which were seen as precursors to the exploitation film genre.[15]

A Victim of Sin (advertised as A Victim of Sin OR Damaged Goods, produced in 1913, had a plot which closely mirrored Brieux's play and was widely regarded as an unauthorized adaptation.[19]

A British silent film adaptation was released in 1919.[20]

Damaged Lives, a 1933 Canadian/American exploitation film, and The Seventh Commandment, a 1932 American exploitation film, were both described by film historian Eric Schaefer as "knockoffs" of Damaged Goods.[17]: 180

Damaged Goods (1937) was an American picture released in 1937 based on Upton Sinclair's novelization of the play.[3]

Notes

editReferences

edit- ^ Sprinchorn, Evert. "Syphilis, the Unmentionable Disease". Ibsen's Kingdom: The Man and His Works, New Haven: Yale University Press, 2021, pp. 307-319. https://doi.org/10.12987/9780300256246-033

- ^ a b Pharand, Michel (1988). "ICONOCLASTS OF SOCIAL REFORM: EUGÈNE BRIEUX AND BERNARD SHAW". Shaw. 8. Penn State University Press: 97–109. JSTOR 40681236.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Pollack, Rhoda-Gale (7 August 2020). "EUGENE BRIEUX'S DAMAGED GOODS (LES AVARIES)". World War One: Plays, Playwrights and Productions.

- ^ a b c ""Damaged Goods"". British Medical Journal. 1 (4339): 327. 4 March 1944. doi:10.1136/bmj.1.4339.327-b. PMC 2283690.

- ^ a b c d e f Brandt, Allan M. (1987). No Magic Bullet: A Social History of Venereal Disease in the United States Since 1880 (Expanded ed.). Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-503469-4.

- ^ Waugh, M A (1974-06-01). "Alfred Fournier, 1832-1914. His influence on venereology". Sexually Transmitted Infections. 50 (3): 232–236. doi:10.1136/sti.50.3.232. ISSN 1368-4973. PMC 1045022. PMID 4602942.

- ^ Brieux, Eugène. "Damaged Goods". Three Plays by Brieux.

- ^ "Eugene Brieux Dies; French Dramatist". New York Times. 7 December 1932. p. 21.

- ^ a b Levine, Louis (19 October 1913). ""Woman is Mistreated and Maltreated and Needs Help," Says Brieux". New York Times.

- ^ a b Guay, Hervé (2008). "La fin de l'âge des pères? La réception du théâtre de Dumas fils, de Brieux et de Bernstein dans les salles « françaises » de Montréal de 1900 à 1918". L'Annuaire théâtral. 43–44 (43–44). Centre de recherche en civilisation canadienne-française (CRCCF) et Société québécoise d'études théâtrales (SQET): 167–180. doi:10.7202/041714ar.

- ^ Durham, Weldon B. (1987). American Theatre Companies, 1888-1930. New York, NY: Greenwood Press.

- ^ "The Stage as a Pulpit of Hygiene". British Medical Journal. 1 (2773): 444. 21 February 1914. JSTOR 25308970.

- ^ Kumm, Elisabeth (March 2016). "Theatre in Melbourne, 1914–18: the best, the brightest and the latest" (PDF). The La Trobe Journal (97).

- ^ a b Bordman, Gerald (1994). "Act Five 1906-1914: The Advance Guard of the New Drama". American Theatre: A Chronicle of Comedy and Drama, 1869-1914. New York, NY: Oxford University Press. p. 720.

- ^ a b Corts, Alicia (16 July 2016). "Syphilis Onstage: Eugène Brieux's Damaged Goods". Notches.

- ^ Schaefer, Eric (1992). "Of hygiene and Hollywood: origins of the exploitation film". Velvet Light Trap.

- ^ a b Schaefer, Eric (1999). "Bold! Daring! Shocking! True!": A History of Exploitation Films, 1919-1959. Duke University Press. ISBN 0-8223-2374-5.

- ^ Briggs, Joe Bob (November 2003). "Kroger Babb's Roadshow". Reason.

- ^ Frykholm, Joel (2009). Framing the Feature Film: Multi-Reel Feature Film and American Film Culture in the 1910s. Acta Universitatis Stockholmiensis. ISBN 978-91-86071-23-3.

- ^ Low, Rachael (1971). History of the British Film, 1918-1929. George Allen & Unwin.

External links

edit- Damaged Goods at Project Gutenberg

- Three Plays by Brieux at Project Gutenberg