This article needs additional citations for verification. (June 2018) |

The Mexican prairie dog (Cynomys mexicanus) is a diurnal burrowing rodent native to north-central Mexico. Treatment as an agricultural pest has led to its status as an endangered species. They are closely related to squirrels, chipmunks, and marmots. Cynomys mexicanus originated about 230,000 years ago from a peripherally isolated population of the more widespread Cynomys ludovicianus.[3]

| Mexican prairie dog | |

|---|---|

| |

| Galeana, Nuevo Leon, Mexico | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | Rodentia |

| Family: | Sciuridae |

| Genus: | Cynomys |

| Species: | C. mexicanus

|

| Binomial name | |

| Cynomys mexicanus Merriam, 1892

| |

Ecology

editThese prairie dogs prefer to inhabit rock-free soil in plains at an altitude of 1,600–2,200 m (5,200–7,200 ft). They are found in the regions of southern Coahuila and northern San Luis Potosí in northern Mexico, where they eat herbs and grasses native to the plains where they live. They acquire all of their water from these plants. Although mainly herbivores, they have been known to eat insects. Predators include coyotes, bobcats, eagles, hawks, badgers, snakes, and weasels.

Northern prairie dogs hibernate and have a shorter mating season, which generally lasts from January to April. After one month's gestation, females give birth to one litter per year, an average of four hairless pups.[4] They are born with eyes closed and use their tails as visual aids until they can see, about 40 days after birth. Weaning occurs during late May and early June, when yearlings may break away from the burrow. Pups leave their mothers by fall.

As they grow older, young play fighting games that involve biting, hissing, and tackling. They reach sexual maturity after one year, with a lifespan of 3–5 years; adults weigh about 1 kg (2.2 lb) and are 14–17 inches (360–430 mm) long, and males are larger than females. Their coloring is yellowish, with darker ears and a lighter belly.

Prairie dogs have one of the most sophisticated languages in the animal world—a system of high-pitched yips and barks—and can run up to 35 mph (56 km/h). As a consequence, their defense mechanism is to sound the alarm, and then get away quickly.[5]

Habitat

editMexican prairie dogs live in excavated colonies, referred to as "towns", which they dig for shelter and protection. A typical town has a funnel-like entrance that slants down into a corridor up to 100 ft (30 m) long, with side chambers for storage and nesting. It has been found that some chambers in these burrows serve specific purposes such as nurseries for new mothers and their young.[6] Prairie dogs have strong muscles in their arms which allow them to dig through the often dense dirt of their habitats. They have even been found to use their teeth to dig, although this is less common.[6] Towns can contain hundreds of animals, but generally have fewer than 50, with a single alpha male. Sometimes, spotted ground squirrels or burrowing owls share the burrow with its rightful owners.

Population structure

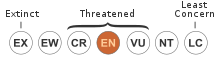

editIn 1956, the Mexican prairie dog was reported as occurring in Coahuila, Nuevo León, and San Luis Potosí. By the 1980s, it had disappeared from Nuevo León. As of 1992 its complete range was roughly 600 km2 (230 sq mi).[7] Viewed as a pest and an obstacle to agriculture and cattle raising due to their burrowing and frequent consumption of crops, it was frequently poisoned, and became endangered in 1994. Mexican prairie dogs currently inhabit less than 4% of their former territory and have suffered a 33% decrease in range between 1996 and 1999.[8]

The current habitat of Mexican prairie dogs is in the region known as El Tokio. These are the grasslands located in the convergence of the states of San Luis Potosí, Nuevo León, and Coahuila. Due to the underground structures in which many prairie dogs live, it is difficult to accurately survey populations. The use of satellite imagery has proven to be helpful in documenting areas in which prairie dogs reside. [9]

Conservation groups such as Pronatura Noreste and Profauna, with the help of donors, carry out conservation efforts for the protection of prairie dogs and associated species, such as shorebirds and birds of prey. Pronatura Noreste, as of February 2007, has signed conservation easements with ejidos and private owners for the protection of more than 42,000 acres (170 km2) of Mexican prairie dog grasslands.

References

edit- ^ Álvarez-Castañeda, S.T.; Lacher, T.; Vázquez, E. (2019). "Cynomys mexicanus". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2019: e.T6089A139607891. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2019-3.RLTS.T6089A139607891.en. Retrieved 19 November 2021.

- ^ "Appendices | CITES". cites.org. Retrieved 2022-01-14.

- ^ Gabriela Castellanos-Morales; Niza Gámez; Reyna A. Castillo-Gámez & Luis E. Eguiarte (2016), "Peripatric speciation of an endemic species driven by Pleistocene climate change: The case of the Mexican prairie dog (Cynomys mexicanus)", Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution, 94 (Pt A): 171–181, Bibcode:2016MolPE..94..171C, doi:10.1016/j.ympev.2015.08.027, PMID 26343460

- ^ Ceballos-G., Gerardo; Wilson, Don E. (1985-12-13). "Cynomys mexicanus". Mammalian Species (248): 1–3. doi:10.2307/3503981. ISSN 0076-3519. JSTOR 3503981.

- ^ Slobodchikoff, C. N., Cognition and Communication in Prairie Dogs (PDF), vol. 32, pp. 257–264

- ^ a b Burns, James A.; Flath, Dennis L.; Clark, Tim W. (1989). "On the Structure and Function of White-Tailed Prairie Dog Burrows". The Great Basin Naturalist. 49 (4): 517–524. ISSN 0017-3614. JSTOR 41712542.

- ^ Ceballos, Gerardo; Mellink, Eric; Hanebury, Louis R. (1993-01-01). "Distribution and conservation status of prairie dogs Cynomys mexicanus and Cynomys ludovicianus in Mexico". Biological Conservation. 63 (2): 105–112. Bibcode:1993BCons..63..105C. doi:10.1016/0006-3207(93)90497-O. ISSN 0006-3207.

- ^ Scott-Morales, Laura; Estrada, Eduardo; ChÁvez-Ramírez, Felipe; Cotera, Mauricio (2004-12-21). "Continued Decline in Geographic Distribution of the Mexican Prairie Dog (Cynomys mexicanus)". Journal of Mammalogy. 85 (6): 1095–1101. doi:10.1644/BER-107.1. ISSN 0022-2372.

- ^ Sidle, John; Johnson, Douglas; Euliss, Betty; Tooze, Marcus (2002), Monitoring Black-Tailed Prairie Dog Colonies With High-Resolution Satellite Imagery (PDF)