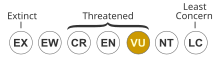

The hellbender (Cryptobranchus alleganiensis), also known as the hellbender salamander, is a species of aquatic giant salamander endemic to the eastern and central United States. It is the largest salamander in North America. A member of the family Cryptobranchidae, the hellbender is the only extant member of the genus Cryptobranchus. Other closely related salamanders in the same family are in the genus Andrias, which contains the Japanese and Chinese giant salamanders. The hellbender is much larger than any other salamander in its geographic range, and employs an unusual adaption for respiration through cutaneous gas exchange via capillaries found in its lateral skin folds. It fills a particular niche — both as a predator and prey — in its ecosystem, which either it or its ancestors have occupied for around 65 million years. The species is listed as Vulnerable on the IUCN Red List of Threatened Species due to the impacts of disease and widespread habitat loss and degradation throughout much of its range.[2]

| Hellbender Temporal range:

Middle Pleistocene – present (~625,000–0 YBP)[1] | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Amphibia |

| Order: | Urodela |

| Family: | Cryptobranchidae |

| Genus: | Cryptobranchus Leuckart, 1821 |

| Species: | C. alleganiensis

|

| Binomial name | |

| Cryptobranchus alleganiensis (Daudin, 1803)

| |

| Subspecies | |

| |

| |

| Distribution of the eastern hellbender (Ozark hellbender not shown) | |

| Synonyms[4][5][6] | |

|

List

| |

Etymology

editThe origin of the name "hellbender" is unclear. The Missouri Department of Conservation says:

The name 'hellbender' probably comes from the animal's odd look. One theory claims the hellbender was named by settlers who thought "it was a creature from hell where it's bent on returning." Another rendition says the undulating skin of a hellbender reminded observers of "horrible tortures of the infernal regions." In reality, it's a harmless aquatic salamander.[7]

In a study conducted in Indiana, informing the public about the rarity and locality of the hellbender resulted in more positive attitudes toward this species than were previously held.[8] Other vernacular names include snot otter,[9] lasagna lizard,[9] devil dog, mud-devil, mud dog, water dog, grampus,[10] Allegheny alligator, and leverian water newt.[5]

The generic name, Cryptobranchus, is derived from the Ancient Greek kryptos (hidden) and branchion (gill).[11] The subspecies name bishopi honors the American herpetologist Sherman C. Bishop.[12][13]

Description

editC. alleganiensis has a flat body and head, with beady dorsal eyes and slimy skin. Like most salamanders, it has short legs with four toes on the front legs and five on its back limbs, and its tail is keeled for propulsion. Its tail is shaped like a rudder, but it is rarely used for swimming; these salamanders use pads on their toes instead to grip rocks and walk up and down streams instead of swimming.[14] The hellbender has working lungs, but gill slits are often retained, although only immature specimens have true gills; the hellbender absorbs oxygen from the water through capillaries of its side frills.[15] The frills run from their neck down to the base of their tail on each side of their body. The frills’ function is to increase the surface area of the hellbender and to help the hellbender breathe.[16] Only occasionally leaving the water, the hellbender makes little use of these lungs and the juveniles lose their external gills after around 18 months or about 125 mm in length.[17][18] Hellbenders use their lungs for buoyancy more than breathing.[14] It is blotchy brown or red-brown in color, with a paler underbelly. Hellbenders can also be described as having a gray, or yellowish-brown, to even black coloration.[19]

Both males and females grow to an adult length of 24 to 40 cm (9.4 to 15.7 in) from snout to vent, with a total length of 30 to 74 cm (12 to 29 in), making them the fourth-largest aquatic salamander species in the world (after the South China giant salamander, the Chinese giant salamander and the Japanese giant salamander, respectively) and the largest amphibian in North America, although this length is rivaled by the reticulated siren of the southeastern United States (although the siren is much leaner in build).[20][21] While males and females grow at similar rates, the females tend to live longer and therefore grow larger.[22] An adult weighs 1.5 to 2.5 kg (3.3 to 5.5 lb), making them the fifth heaviest living amphibian in the world after their South China, Chinese and Japanese cousins and the goliath frog, while the largest cane toads may also weigh as much as a hellbender. Hellbenders reach sexual maturity at about five years of age, and may live 30 years in captivity.[15]

The hellbender has a few characteristics that make it distinguishable from other native salamanders, including a gigantic, dorsoventrally flattened body with thick folds travelling down the sides, a single open gill slit on each side, and hind feet with five toes each.[23][24] Easily distinguished from most other endemic salamander species simply by their size, hellbenders average up to 60 cm or about 2 ft in length; the only species requiring further distinction (due to an overlap in distribution and size range) is the common mudpuppy (Necturus maculosus).[25][21] This demarcation can be made by noting the presence of external gills in the mudpuppy, which are lacking in the hellbender, as well as the presence of four toes on each hind foot of the mudpuppy (in contrast with the hellbender's five).[23] Furthermore, the average size of C. a. alleganiensis has been reported to be 45–60 cm (with some reported as reaching up to 74 cm or 30 in), while N. m. maculosus has a reported average size of 28 to 40 cm (11 to 16 in) in length, which means that hellbender adults will still generally be notably larger than even the biggest mudpuppies.[25][26][27]

Taxonomy

editThe genus Cryptobranchus has historically been considered to contain only one species, C. alleganiensis, with two subspecies, C. a. alleganiensis and C. a. bishopi.[21] A recent decline in population size of the Ozark subspecies C. a. bishopi has led to further research into populations of this subspecies, including genetic analysis to determine the best method for conservation.[25] Crowhurst et al., for instance, found that the "Ozark subspecies" denomination is insufficient for describing genetic (and therefore evolutionary) divergence within the genus Cryptobranchus in the Ozark region. They found three equally divergent genetic units within the genus: C. a. alleganiensis, and two distinct eastern and western populations of C. a. bishopi. These three groups were shown to be isolated, and are considered to most likely be "diverging on different evolutionary paths".[25]

Distribution

editHellbenders are present in a number of Eastern US states, from southern New York to northern Georgia,[28] including parts of Ohio, Pennsylvania, Maryland, West Virginia, Virginia, Kentucky, Illinois, Indiana, Tennessee, North Carolina, South Carolina, Alabama, Mississippi, Arkansas, Missouri, and extending into Oklahoma and Kansas. The subspecies (or species, depending on the source) C. a. bishopi is confined to the Ozarks of northern Arkansas and southern Missouri, while C. a. alleganiensis is found in the rest of these states.[29]

Some hellbender populations—namely a few in Missouri, Pennsylvania, and Tennessee—have historically been noted to be quite abundant, but several man-made threats have converged on the species such that it has seen a serious population decline throughout its range.[30] In Missouri, it is estimated that the populations have declined by 77% since the 1980s.[31] Hellbender populations were listed in 1981 as already extirpated or endangered in Illinois, Indiana, Iowa, and Maryland, decreasing in Arkansas and Kentucky, and generally threatened as a species throughout their range by various human activities and developments.[29]

Ecology

editHellbenders are found in clear, clean water and their presence is an indicator that the water is good quality.[32] The hellbender salamander, considered a "habitat specialist", has adapted to fill a specific niche within a very specific environment, and is labeled as such "because its success is dependent on a constancy of dissolved oxygen, temperature and flow found in swift water areas", which in turn limits it to a narrow spectrum of stream/river choices.[28] As a result of this specialization, hellbenders are generally found in areas with large, irregularly shaped, and intermittent rocks and swiftly moving water, while they tend to avoid wider, slow-moving waters with muddy banks and/or slab rock bottoms. This specialization likely contributed to the decline in their populations, as collectors could easily identify their specific habitats.[28] One collector noted, at one time, "one could find a specimen under almost every suitable rock", but after years of collecting, the population had declined significantly.[33] The same collector noted, he "never found two specimens under the same rock", corroborating the account given by other researchers that hellbenders are generally solitary; they are thought to gather only during the mating season.[33][34] If rocks are lacking, hellbenders have been known to use holes in stream banks as habitat.[32] On average, their home range is estimated to be 198 square meters as of 2005.[35] The ideal habitat for a hellbender has a large amount of gravel, low pH, cool water temperatures, and low specific conductivity. The large amounts of gravel enable the hellbender to hide, cool water temperatures allow for more efficient cutaneous gas exchange, and low specific conductivity may indicate an undisturbed stream. Hellbender communities may be more concentrated in undisturbed areas.[32]

Both subspecies, C. a. alleganiensis and C. a. bishopi undergo a metamorphosis after around a year and a half of life.[28] At this point, when they are roughly 13.5 cm (5.3 in) long, they lose the gills present during their larval stage. Until then, they are easily confused with mudpuppies, and can be differentiated often only through toe number.[15] After this metamorphosis, hellbenders must be able to absorb oxygen through the folds in their skin, which is largely behind the need for fast-moving, oxygenated water. If a hellbender ends up in an area of slow-moving water, not enough of it will pass over its skin in a given time, making it difficult to garner enough oxygen to support necessary respiratory functions. A below-favorable oxygen content can make life equally difficult.[33]

Hellbenders are preyed upon by diverse predators, including various fish and reptiles (including both snakes and turtles). Particularly, largemouth bass is a predator that can consume a hellbender 1–3 years old.[36] Cannibalism of eggs is also considered a common occurrence.[21] One study found that in areas with increased deforestation, the likelihood of filial cannibalism increases.[37]

In another study by Kenison & Wilson (2018), researchers found that young, captive hellbenders showed altered behavior in response to predatory fish nearby. Because of their altered behavior, it was observed and concluded that hellbenders are capable of detecting kairomones, which are chemical cues emitted by predatory species. This suggests that hellbenders can recognize kairomones as stressful stimuli and identify potential predators.[36]

Life history and behavior

editBehavior

editOnce a hellbender finds a favorable location, it generally does not stray too far from it—except occasionally for breeding and hunting—and will protect it from other hellbenders both in and out of the breeding season.[34] While the range of two hellbenders may overlap, they are noted as rarely being present in the overlapping area when the other salamander is in the area. The species is at least somewhat nocturnal, with peak activity being reported by one source as occurring around "two hours after dark" and again at dawn (although the dawn peak was recorded in the lab and could be misleading as a result).[34][15] Nocturnal activity has been found to be most prevalent in early summer, perhaps coinciding with highest water depths. Adult hellbenders can live up to 25–30 years. [38]

Diet

editC. alleganiensis feeds primarily on crayfish and small fish, but also insects, worms, molluscs, tadpoles and smaller salamanders.[39][40] A study conducted in 2017 found that larval hellbenders eat mayfly and caddisfly nymphs.[41] One report, written by a commercial collector in the 1940s, noted a trend of more crayfish predation in the summer during times of higher prey activity, whereas fish made up a larger part of the winter diet, when crayfish are less active. There seems to be a specific temperature range in which hellbenders feed, as well: between 45 and 80 °F (7 and 27 °C). Cannibalism—mainly on eggs—has been known to occur within hellbender populations. One researcher claimed perhaps density is maintained, and density dependence in turn created, in part by intraspecific predation.[34][28][15] When feeding on large prey items relative to themselves, it has been found that they use suction feeding.[42]

Reproduction

editThe hellbenders' breeding season begins in late August or early- to mid-September and can continue as late as the end of November, depending on region. They exhibit no sexual dimorphism, except during the fall mating season, when males have a bulging ring around their cloacal glands. Unlike most salamanders, the hellbender performs external fertilization. Before mating, each male excavates a brood site, a saucer-shaped depression under a rock or log, with its entrance positioned out of the direct current, usually pointing downstream. The male remains in the brood site awaiting a female. When a female approaches, the male guides or drives her into his burrow and prevents her from leaving until she oviposits.[15]

Female hellbenders lay 150–200 eggs over a two- to three-day period; the eggs are 18–20 mm (0.71–0.79 in) in diameter, connected by five to ten cords. As the female lays eggs, the male positions himself alongside or slightly above them, spraying the eggs with sperm while swaying his tail and moving his hind limbs, which disperses the sperm uniformly. The male often tempts other females to lay eggs in his nest, and as many as 1,946[43] eggs have been counted in a single nest. Males also exhibit mate and shelter guarding. Mortality rate is high for hellbender eggs.[44] Studies have found that until the female successfully reproduces, the male hellbender will guard her in his territory until the reproduction is complete. Cannibalism, however, leads to a much lower number of eggs in hellbender nests than would be predicted by egg counts.[15] Adult males are more likely to cannibalize their own offspring in degraded sites with limited food availability.[45]

After oviposition, the male drives the female away from the nest and guards the eggs. Incubating males rock back and forth and undulate their lateral skin folds, which circulates the water, increasing oxygen supply to both eggs and adult. Incubation lasts from 45 to 75 days, depending on region.[15] Males are known to show solitary parental care for the eggs and larvae for at least 7–8 months.[46]

Hatchling hellbenders are 25–33 mm (0.98–1.30 in) long, have a yolk sac as a source of energy for the first few months of life, and lack functional limbs.[15]

Adaptations

editHellbenders are superbly adapted to the shallow, fast-flowing, rocky streams in which they live. Their flattened shape offers little resistance to the flowing water, allowing them to work their way upstream and also to crawl into narrow spaces under rocks. The wrinkles and folds along their skin are used to expand surface area for cutaneous respiration.[47] Their skin also has a secretion that is important for innate immunity against chytrid activity.[48] Although their eyesight is relatively poor, they have light-sensitive cells all over their bodies. Those on their tails are especially finely tuned and may help them position safely under rocks without their tails poking out to give themselves away. They have a good sense of smell and move upstream in search of food such as dead fish, following the trail of scent molecules. Smell is possibly their most important sense when hunting. They also have a lateral line similar to those of fish, with which they can detect vibrations in the water.[49]

Conservation status

editResearch throughout the range of the hellbender has shown a dramatic decline in populations in the majority of locations. As of 2022, the species is classified as Vulnerable by the IUCN.[2] Many different anthropogenic sources have contributed to this decline, including the siltation and sedimentation, blocking of dispersal/migration routes, and destruction of riverine habitats created by dams and other development, as well as pollution, disease and overharvesting for commercial and scientific purposes.[29][27] As many of these detrimental effects have irreversibly damaged hellbender populations, it is important to conserve the remaining populations through protecting habitats and—perhaps in places where the species was once endemic and has been extirpated—by augmenting numbers through reintroduction.[29]

Due to sharp decreases seen in the Ozark subspecies, researchers have been trying to differentiate C. a. alleganiensis and C. a. bishopi into two management units. Indeed, researchers found significant genetic divergence between the two groups, as well as between them and another isolated population of C. a. alleganiensis. This could be reason enough to ensure work is done on both subspecies, as preserving extant genetic diversity is of crucial ecological importance.[29]

The Ozark hellbender has been listed as an endangered species under the Endangered Species Act by the US Fish and Wildlife Service since October 5, 2011. This hellbender subspecies inhabits the White River and Spring River systems in southern Missouri and northern Arkansas, and its population has declined an estimated 75% since the 1980s, with only about 590 individuals remaining in the wild. Degraded water quality, habitat loss resulting from impoundments, ore and gravel mining, sedimentation, and collection for the pet trade are thought to be the main factors resulting in the amphibian's decline.[50] When chytridiomycosis killed 75% of the St. Louis Zoo's captive hellbender population between March 2006 and April 2007, tests began to be conducted on wild populations. The disease has been detected in all Missouri populations of the Ozark hellbender.[51] NatureServe treats C. a. alleganiensis as an Imperiled Subspecies, C. a. bishopi as a Critically Imperiled Subspecies, and the species as a whole as Vulnerable.[52][53][54]

The Ozark hellbender was successfully bred in captivity for the first time at the St. Louis Zoo, in a joint project with the Missouri Department of Conservation, hatching on November 15, 2011.[55]

Apart from the Ozark efforts, head-starting programs, in which eggs are collected from the wild and raised in captivity for re-release at a less vulnerable stage, have been initiated in Indiana, New York,[56] and Ohio.[57]

Members of the Pennsylvania State Senate have voted to approve the eastern hellbender as the official state amphibian in an effort to raise awareness about its endangered status. The legislation has been mired in controversy due to a dispute by House members who argue that Wehrle's salamander should be given the honor.[58][59] The legislation did not pass in 2018, but was reintroduced in 2019.[60] On April 23, 2019, Pennsylvania Governor Tom Wolf signed legislation making the eastern hellbender Pennsylvania's official state amphibian.[61] Youth members of the Chesapeake Bay Foundation's Pennsylvania Student Leadership Council were heavily involved writing and advocating on behalf of this legislation. They hope that the success of the hellbender bill in the Pennsylvania Senate will contribute to clean water efforts and raise awareness for the hellbender's struggling population.[62]

Threats

editThe hellbender faces an array of challenges that jeopardize its habitat and overall well-being. These challenges include habitat degradation, habitat modifications, pollution, and the looming threat of emerging diseases. The conservation of this species is of paramount importance to ensure its continued existence in the wild.[2]

The hellbender faces a significant threat due to habitat degradation, primarily caused by activities like dam construction, which disrupts water flow and submerges vital riffle habitats. Logging, mining, and road construction contribute to sedimentation, covering essential nesting and shelter sites. Chemical pollutants and misconceptions about the species have led to declines. Over-collection for sale and deliberate eradication efforts have also been detrimental.[2]

The salamander's habitat is further jeopardized by habitat modifications stemming from industrialization and urbanization, including increased stream channelization and pollution from agricultural runoff, mining, and thermal pollution. Diseases, like Batrachochytrium dendrobatidis (Bd) and Ranavirus infections, have been detected in hellbender populations, contributing to population declines.[2]

An emerging disease threat is the salamander chytrid fungus (Batrachochytrium salamandrivorans, or "Bsal"), which has caused severe declines in other salamander species. Although not confirmed in the Americas, Bsal's potential introduction poses a substantial risk. If introduced, the impacts on hellbender populations could be swift and severe, necessitating immediate mitigation measures.[2]

See also

edit- Necturus alabamensis (Alabama waterdog)

- Necturus beyeri (Gulf coast waterdog)

References

edit- ^ Bredehoeft, Keila E.; Schubert, Blaine W. (2015). "A re-evaluation of the Pleistocene hellbender, Cryptobranchus guildayi ". Journal of Herpetology. 49: 157–160. doi:10.1670/12-222. S2CID 84731832.

- ^ a b c d e f g IUCN SSC Amphibian Specialist Group. (2022). "Cryptobranchus alleganiensis". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2022: e.T59077A82473431. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2022-2.RLTS.T59077A82473431.en.

- ^ Listed by United States of America

- ^ Dundee, Harold A. (1971). "Cryptobranchus alleganiensis". Catalogue of American Amphibians and Reptiles (Report). American Society of Ichthyologists and Herpetologists. Account 101.

- ^ a b Nickerson, Max Allen; Mays, Charles Edwin (1973). The Hellbenders: North American "giant salamanders". Publications in Biology and Geology. Vol. 1. Milwaukee Public Museum.

- ^ Stejneger, L.; Barbour, T. (1917). "Cryptobranchus alleganiensis". A Check List of North American Amphibians and Reptiles. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. p. 7.

- ^ Johnson, Tom R.; Briggler, Jeff (2004). The Hellbender (PDF) (Report). Herpetology Lab. Jefferson City, MO: The Conservation Commission of the State of Missouri. Archived from the original (PDF) on 3 May 2017. Retrieved 16 May 2013.

- ^ Reimer, A.; Mase, A.; Mulvaney, K.; Mullendore, N.; Perry-Hill, R.; Prokopy, L. (June 2014) [22 October 2013]. "The impact of information and familiarity on public attitudes toward the eastern hellbender" (PDF). Animal Conservation. 17 (3): 235–243. doi:10.1111/acv.12085 – via ag.purdue.edu.

- ^ a b Sofia, Madeline K. (14 September 2017). "Snot otters get a second chance in Ohio". National Public Radio.

Snot otter; lasagna lizard: Pick your favorite nickname for the Eastern hellbender salamander.

- ^ "grampus". Dictionary of American Regional English. Madison, WI: University of Wisconsin. Spring 2020. Quarterly update 20 – via dare.wisc.edu.

- ^ Miller, Jessica J. "Cryptobranchus alleganiensis". amphibiainfo.com. Caudata database. livingunderworld.org. Archived from the original on 11 January 2014. Retrieved 12 November 2012.

- ^ Beltz, Ellin (2006). "Bishop, Sherman Chauncey". Scientific and Common Names of the Reptiles and Amphibians of North America — Explained.

- ^ Beolens, Bo; Watkins, Michael; Grayson, Michael (2013). "Cryptobranchus alleganiensis bishopi". The Eponym Dictionary of Amphibians. Exeter, UK: Pelagic Publishing Ltd. p. 23. ISBN 978-1-907807-41-1.

- ^ a b Humphries, Jeffrey W; & Pauley, Thomas K. (2005). Life History of the Hellbender, Cryptobranchus alleganiensis, in a West Virginia Stream. The American Midland Naturalist, 154(1), 135–142. https://doi.org/10.1674/0003-0031(2005)154[0135:LHOTHC]2.0.CO;2

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Mayasich, J.; Grandmaison, D.; Phillips, C. (June 2003) Eastern Hellbender Status Assessment Report

- ^ Pugh, M. W.; Groves, J.D.; Williams, L.A.; Gangloff, M.M. (2013). "A previously undocumented locality of eastern hellbenders (Cryptobranchus alleganiensis alleganiensis) in the Elk River, Carter County, TN". Southeastern Naturalist. 12 (1): 137–142. doi:10.1656/058.012.0111.

- ^ Unger, Shem D.; Jr, Olin E. Rhodes; Sutton, Trent M.; Williams, Rod N. (2013-10-18). "Population Genetics of the Eastern Hellbender (Cryptobranchus alleganiensis alleganiensis) across Multiple Spatial Scales". PLOS ONE. 8 (10): e74180. Bibcode:2013PLoSO...874180U. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0074180. ISSN 1932-6203. PMC 3800131. PMID 24204565.

- ^ Hellbender salamander. The Nature Conservancy. (n.d.). Retrieved April 20, 2022, from https://www.nature.org/en-us/get-involved/how-to-help/animals-we-protect/hellbender-salamander/

- ^ Powell, Robert; Conant, Roger; Collins, Joseph T. (2016). Peterson Field Guide to Reptiles and Amphibians of Eastern and Central North America (4th ed.). HarperCollins.

- ^ "Newly described Chinese giant salamander may be world's largest amphibian". 17 September 2019.

- ^ a b c d Cryptobranchus alleganiensis AmphibiaWeb: Information on amphibian biology and conservation. [web application]. 2012. Berkeley, California: AmphibiaWeb. Available: http://amphibiaweb.org/. (Accessed: 15 November 2012).

- ^ Taber, Charles A.; Wilkinson, R. F.; Topping, Milton S. (1975). "Age and Growth of Hellbenders in the Niangua River, Missouri". Copeia. 1975 (4): 633–639. doi:10.2307/1443315. ISSN 0045-8511. JSTOR 1443315.

- ^ a b Guimond, R.W.; Hutchison, V.H. (21 December 1973). "Aquatic Respiration: An Unusual Strategy in the Hellbender Cryptobranchus alleganiensis alleganiensis (Daudin)". Science. 182 (4118): 1263–1265. Bibcode:1973Sci...182.1263G. doi:10.1126/science.182.4118.1263. PMID 17811319. S2CID 43586570.

- ^ Gehlbach, Frederick R. (1960). "Comments on the Study of Ohio Salamanders with Key to Their Identification". Journal of the Ohio Herpetological Society. 2 (3): 40–45.

- ^ a b c d Crowhurst, R.S.; Faries, K.M.; Collantes, J.; Briggler, J.T.; Koppelman, J.B.; Eggert, L.S. (28 December 2010). "Genetic relationships of hellbenders in the Ozark highlands of Missouri and conservation implications for the Ozark subspecies (Cryptobranchus alleganiensis bishopi)". Conservation Genetics. 12 (3): 637–646. doi:10.1007/s10592-010-0170-0. S2CID 24257951.

- ^ Lanza, B.; Vanni, S.; Nistri, A. (1998). Cogger, Harold G.; Zweifel, Richard G. (eds.). Encyclopedia of Reptiles & Amphibians (2nd ed.). San Diego, CA: Academic Press. pp. 70–74. ISBN 978-0121785604.

- ^ a b Sabatino, Stephen J.; Routman, Eric J. (October 2009). "Phylogeography and conservation genetics of the hellbender salamander (Cryptobranchus alleganiensis)". Conservation Genetics. 10 (5): 1235–1246. Bibcode:2009ConG...10.1235S. doi:10.1007/s10592-008-9655-5. S2CID 12703020.

- ^ a b c d e Peterson, C.L; Metter, D.E.; Miller, B.T.; Wilkinson, R.F.; Topping, M.S. (April 1988). "Demography of the Hellbender Cryptobranchus alleganiensis in the Ozarks". American Midland Naturalist. 199 (2): 291–303. doi:10.2307/2425812. JSTOR 2425812. S2CID 85842376.

- ^ a b c d e Williams, R.D.; Gates, J.T.; Hocutt, C.H; Taylor, G.J. (1981). "The Hellbender: A Nongame Species in Need of Management". Wildlife Society Bulletin. 9 (2): 94–100. JSTOR 3781577.

- ^ Albanese, Brett; Jensen, John B.; Unger, Shem D. (2011). "'Occurrence of the Eastern Hellbender (Cryptobranchus alleganiensis alleganiensis) in the Coosawattee River System (Mobile River Basin), Georgia". Southeastern Naturalist. 10 (1): 181–184. doi:10.1656/058.010.0116. S2CID 84971915.

- ^ Catherine M. Bodinof, Jeffrey T. Briggler, Randall E. Junge, Tony Mong, Jeff Beringer, Mark D. Wanner, Chawna D. Schuette, Jeff Ettling, Joshua J. Millspaugh; Survival and Body Condition of Captive-Reared Juvenile Ozark Hellbenders (Cryptobranchus alleganiensis bishopi) Following Translocation to the Wild. Copeia 30 March 2012; 2012 (1): 150–159. doi: https://doi.org/10.1643/CH-11-024

- ^ a b c Keitzer, S. C., Pauley, T. K., & Burcher, C. L. (2013). Stream characteristics associated with site occupancy by the eastern hellbender, Cryptobranchus alleganiensis alleganiensis, in southern West Virginia. Northeastern Naturalist, 20(4), 666–677.

- ^ a b c Swanson, P.L. (September 1948). "Notes on the Amphibians of Venango County, Pennsylvania". American Midland Naturalist. 40 (2): 362–371. doi:10.2307/2421606. JSTOR 2421606. S2CID 87410957.

- ^ a b c d Humphries, W.J.; Pauley, T.K. (December 2000). "Seasonal Changes in Nocturnal Activity of the Hellbender, Cryptobranchus alleganiensis, in West Virginia". Journal of Herpetology. 34 (4): 604–607. doi:10.2307/1565279. JSTOR 1565279.

- ^ W. JEFFREY HUMPHRIES and THOMAS K. PAULEY "Life History of the Hellbender, Cryptobranchus alleganiensis, in a West Virginia Stream," The American Midland Naturalist 154(1), 135–142, (1 July 2005). https://doi.org/10.1674/0003-0031(2005)154[0135:LHOTHC]2.0.CO;2

- ^ a b Kenison, Erin K.; Williams, Rod N. (2018). "Training for Translocation: Predator Conditioning Induces Behavioral Plasticity and Physiological Changes in Captive Eastern Hellbenders (Cryptobranchus alleganiensis alleganiensis) (Cryptobranchidae, Amphibia)". Diversity. 10 (1): 13. doi:10.3390/d10010013. ISSN 1424-2818.

- ^ Hopkins, William A., et al. "Filial cannibalism leads to chronic nest failure of eastern hellbender salamanders (Cryptobranchus alleganienesis)." The American Naturalist 202.1 (2023).

- ^ Kaunert, M. D., Brown, R. K., Spear, S., Johantgen, P. B., & Popescu, V. D. (2023). Restoring eastern hellbender (Cryptobranchus a. alleganiensis) populations through translocation of headstarted individuals. Population Ecology.

- ^ "Cryptobranchus alleganiensis (Hellbender)". Animal Diversity Web.

- ^ "AmphibiaWeb - Cryptobranchus alleganiensis".

- ^ Kirsten A. Hecht, Max A. Nickerson, Phillip B. Colclough "Hellbenders (Cryptobranchus alleganiensis) May Exhibit an Ontogenetic Dietary Shift," Southeastern Naturalist, 16(2), 157–162, (1 June 2017)

- ^ Deban, Stephen M.; O’Reilly, James C. (2005). "The ontogeny of feeding kinematics in a giant salamander Cryptobranchus alleganiensis: Does current function or phylogenetic relatedness predict the scaling patterns of movement?". Zoology. 108 (2): 155–167. doi:10.1016/j.zool.2005.03.006. ISSN 0944-2006. PMID 16351963.

- ^ Chris Mattison (2005). Encyclopedia of Reptiles and Amphibians. The Brown Reference Group. p. 23.

- ^ Kaunert, M. D., Brown, R. K., Spear, S., Johantgen, P. B., & Popescu, V. D. (2023). Restoring eastern hellbender (Cryptobranchus a. alleganiensis) populations through translocation of headstarted individuals. Population Ecology.

- ^ Hopkins, William A.; Case, Brian F.; Groffen, Jordy; Brooks, George C.; Bodinof Jachowski, Catherine M.; Button, Sky T.; Hallagan, John J.; O’Brien, Rebecca S. M.; Kindsvater, Holly K. (2023-07-01). "Filial Cannibalism Leads to Chronic Nest Failure of Eastern Hellbender Salamanders ( Cryptobranchus alleganiensis )". The American Naturalist. 202 (1): 92–106. doi:10.1086/724819. ISSN 0003-0147. PMID 37384763.

- ^ Galligan, Thomas M.; Helm, Richard F.; Case, Brian F.; Bodinof Jachowski, Catherine M.; Frazier, Clara L.; Alaasam, Valentina; Hopkins, William A. (2021-11-01). "Pre-breeding androgen and glucocorticoid profiles in the eastern hellbender salamander (Cryptobranchus alleganiensis alleganiensis)". General and Comparative Endocrinology. 313: 113899. doi:10.1016/j.ygcen.2021.113899. ISSN 0016-6480. PMID 34499909.

- ^ "Hellbender Salamander". The Nature Conservancy. Retrieved 2023-01-24.

- ^ Hardman, Rebecca H.; Reinert, Laura K.; Irwin, Kelly J.; Oziminski, Kendall; Rollins-Smith, Louise; Miller, Debra L. (2023-02-03). "Disease state associated with chronic toe lesions in hellbenders may alter anti-chytrid skin defenses". Scientific Reports. 13 (1): 1982. Bibcode:2023NatSR..13.1982H. doi:10.1038/s41598-023-28334-4. ISSN 2045-2322. PMC 9898527. PMID 36737574.

- ^ Mattison, Chris (2005). "What is an amphibian?". Encyclopedia of Reptiles and Amphibians. Rochester, Kent: Grange Books. p. 22. ISBN 978-1-84013-794-1.

- ^ "U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Lists the Ozark Hellbender as Endangered and Moves to Include Hellbenders in Appendix III of CITES" (Press release). U. S. Fish and Wildlife Service. 2011-10-05. Retrieved 16 May 2013.

- ^ "The Ozark Hellbender – Can We Save It?". U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. Retrieved 26 January 2013.

- ^ "NatureServe Explorer 2.0". explorer.natureserve.org. Retrieved 28 March 2022.

- ^ "NatureServe Explorer 2.0". explorer.natureserve.org. Retrieved 28 March 2022.

- ^ "NatureServe Explorer 2.0". explorer.natureserve.org. Retrieved 28 March 2022.

- ^ Saint Louis Zoo (1 December 2011). "World's first captive breeding of Ozark hellbenders". ScienceDaily. Retrieved 15 November 2012.

- ^ James, Will (20 August 2013). "The Buffalo Zoo's Hellbender Lab". Wall Street Journal.

- ^ "Ohio's Hellbender Population Set Up for Success" (Press release). Ohio Department of Natural Resources. 9 October 2014. Retrieved 10 January 2015.

- ^ Frank Kummer, "Seriously? Battle looms over Pa. state amphibian: Hellbender vs. Wehrle's", Philadelphia Inquirer, November 16, 2017, http://www.philly.com/philly/health/hellbender-snot-otter-pennsylvanias-official-amphibian-20171116.html

- ^ "The hellbender is one step closer to becoming the official PA state amphibian".

- ^ B. J. Small, "The Hellbender is One Step Closer to Becoming the Official PA State Amphibian", York Daily Record, January 29, 2019.

- ^ "Bill Information - Senate Bill 9; Regular Session 2019-2020".

- ^ Bulletin, Bay (2019-04-16). "Hellbender Poised to Become Pa. State Amphibian". Chesapeake Bay Magazine. Retrieved 2023-11-07.

Further reading

edit- Bishop SC (1943). Handbook of Salamanders: The Salamanders of the United States, and of Lower California. Ithaca and London: Comstock Publishing Associates, a division of Cornell University Press. 508 pp. (Cryptobranchus allegheniensis, pp. 59–62; C. bishopi, p. 63).

- Grobman AB (1943). "Notes on Salamanders with the Description of a New Species of Cryptobranchus ". Occ. Pap. Mus. Zool. Univ. Michigan (470): 1–13. (Cryptobranchus bishopi, new species).

- Petranka, James W. (1998). Salamanders of the United States and Canada. Washington and London: Smithsonian Institution Press.

Karel Čapek War with the Newts (Válka s Mloky in the original Czech), also translated as Salamander Wars, is a 1936 satirical science fiction novel by Czech author Karel Čapek

External links

edit- Hellbender Cryptobranchus alleganiensis field guide from the Missouri Department of Conservation

- Eastern hellbender information at Commonwealth of Virginia.

- Eastern Hellbender Fact Sheet at New York State.

- Cryptobranchus at CalPhotos.