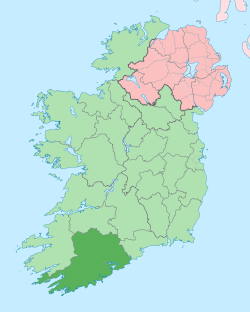

County Cork (Irish: Contae Chorcaí) is the largest and the southernmost county of Ireland, named after the city of Cork, the state's second-largest city. It is in the province of Munster and the Southern Region. Its largest market towns are Mallow, Macroom, Midleton, and Skibbereen. As of 2022[update], the county had a population of 584,156, making it the third-most populous county in Ireland. Cork County Council is the local authority for the county, while Cork City Council governs the city of Cork and its environs. Notable Corkonians include Michael Collins, Jack Lynch, Roy Keane, Sonia O'Sullivan, Cillian Murphy and Graham Norton.

County Cork

Contae Chorcaí | |

|---|---|

| Nickname: The Rebel County | |

| |

| Coordinates: 52°0′N 8°45′W / 52.000°N 8.750°W | |

| Country | Ireland |

| Province | Munster |

| Region | Southern |

| Established | 1606[1] |

| County town | Cork |

| Government | |

| • Local authority | Cork County Council |

| • Dáil constituencies | |

| • EP constituency | South |

| Area | |

| • Total | 7,508 km2 (2,899 sq mi) |

| • Rank | 1st |

| Highest elevation (Knockboy) | 706 m (2,316 ft) |

| Population (2022)[4] | |

| • Total | 584,156 |

| • Rank | 3rd |

| • Density | 78/km2 (200/sq mi) |

| Demonym | Corkonian |

| Time zone | UTC±0 (WET) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC+1 (IST) |

| Eircode routing keys | P12, P14, P17, P24, P25, P31, P32, P36, P43, P47, P51, P56, P61, P67, P72, P75, P81, P85, T12, T23, T34, T45, T56 (primarily) |

| Telephone area codes | 02x, 063 (primarily) |

| ISO 3166 code | IE-CO |

| Vehicle index mark code | C |

| Website | www |

| |

Cork borders four other counties: Kerry to the west, Limerick to the north, Tipperary to the north-east and Waterford to the east. The county contains a section of the Golden Vale pastureland that stretches from Kanturk in the north to Allihies in the south. The south-west region, including West Cork, is one of Ireland's main tourist destinations,[5] known for its rugged coast and megalithic monuments and as the starting point for the Wild Atlantic Way. The largest third-level institution is University College Cork, founded in 1845, and has a total student population of around 22,000.[6] Local industry and employers include technology company Dell EMC, the European headquarters of Apple, and the farmer-owned dairy co-operative Dairygold.

The county is known as the "rebel county", a name given to it by King Henry VII of England for its support, in a futile attempt at a rebellion in 1491, of Perkin Warbeck, who claimed to be Richard of Shrewsbury, Duke of York.

Political and governance

editThe local government areas of county Cork and the city of Cork are administered by the local authorities of Cork County Council and Cork City Council respectively. The boundary between these two areas was altered by the 2019 Cork boundary change. It is part of the Southern Region and has five representatives on the Southern Regional Assembly.[7]

For elections to Dáil Éireann, the city and county are divided into five constituencies: Cork East, Cork North-Central, Cork North-West, Cork South-Central and Cork South-West. Together they return 18 deputies (TDs) to the Dáil.[8] It is part of the South constituency for European elections.[9]

Geography

editCork is the largest county in Ireland by land area, and the largest of Munster's six counties by population and area. At the latest census in 2022, the population of the entire county stood at 584,156. Cork is the second-most populous county in the State, and the third-most populous county on the island of Ireland.

County Cork is located in the province of Munster, bordering Kerry to the west, Limerick to the north, Tipperary to the north-east and Waterford to the east. The county shares separate mountainous borders with Tipperary and Kerry. The terrain on the Kerry border was formed between 360 and 374 million years ago, as part of the rising of the MacGillycuddy's Reeks and Caha Mountains mountains ranges. This occurred during the Devonian period when Ireland was part of a larger continental landmass and located south of the equator.[10][11] The region's topography of peaks and valleys are characterised by steep ridges formed during the Hercynian period of folding and mountain formation some 300 million years ago.[10]

Twenty-four historic baronies are in the county—the most of any county in Ireland. While baronies continue to be officially defined units, they are no longer used for many administrative purposes. Their official status is illustrated by Placenames Orders made since 2003, where official Irish names of baronies are listed.[citation needed] The county has 253 civil parishes.[12] Townlands are the smallest officially defined geographical divisions in Ireland, with about 5447 townlands in the county.

Mountains and upland habitats

editThe county's mountains rose during a period mountain formation some 374 to 360 million years ago and include the Slieve Miskish and Caha Mountains on the Beara Peninsula, the Ballyhoura Mountains on the border with Limerick and the Shehy Mountains which contain Knockboy (706 m), the highest point in Cork. The Shehy Mountains are on the border with Kerry and may be accessed from the area known as Priests Leap, near the village of Coomhola. The upland areas of the Ballyhoura, Boggeragh, Derrynasaggart, and Mullaghareirk Mountain ranges add to the range of habitats found in the county. Important habitats in the uplands include blanket bog, heath, glacial lakes, and upland grasslands. Cork has the 13th-highest county peak in Ireland.

Rivers and lakes

editThree rivers, the Bandon, Blackwater, and Lee, and their valleys dominate central Cork.[original research?] Habitats of the valleys and floodplains include woodlands, marshes, fens, and species-rich limestone grasslands. The River Bandon flows through several towns, including Dunmanway to the west of the town of Bandon before draining into Kinsale Harbour on the south coast. Cork's sea loughs include Lough Hyne and Lough Mahon, and the county also has many small lakes. An area has formed where the River Lee breaks into a network of channels weaving through a series of wooded islands, forming 85 hectares of swampland around Cork's wooded area. The Environmental Protection Agency carried out a survey of surface waters in County Cork between 1995 and 1997, which identified 125 rivers and 32 lakes covered by the regulations.

Land and forestry

editLike many parts of Munster, Cork has fertile agricultural land and many bog and peatlands. Cork has around 74,000 hectares of peatlands, which amount to 9.8% of the county's total land area. Cork has the highest share of the national forest area, with around 90,020 ha (222,400 acres) of forest and woodland area, constituting 11.6% of the national total and approximately 12% of Cork's land area.[13] It is home to one of the last remaining pieces of native woodland in Ireland and Europe.[14]

Wildlife

editThe hooded crow, Corvus cornix is a common bird, particularly in areas nearer the coast. Due to this bird's ability to (rarely) prey upon small lambs, the gun clubs of County Cork have killed many of these birds in modern times.[15] A collection of the marine algae was housed in the herbarium of the botany department of the University College Cork.[16] Parts of the South West coastline are hotspots for sightings of rare birds, with Cape Clear being a prime location for bird watching.[17][18] The island is also home to one of only a few gannet colonies around Ireland and the UK. The coastline of Cork is sometimes associated with whale watching, with some sightings of fin whales, basking sharks, pilot whales, minke whales, and other species.[19][20][21]

Coastline

editCork has a mountainous and flat landscape with many beaches and sea cliffs along its coast. The southwest of Ireland is known for its peninsulas and some in Cork include the Beara Peninsula, Sheep's Head, Mizen Head, and Brow Head. Brow Head is the most southerly point of mainland Ireland. There are many islands off the coast of the county, in particular, off West Cork. Carbery's Hundred Isles are the islands around Long Island Bay and Roaringwater Bay.

Fastnet Rock lies in the Atlantic Ocean 11.3 km south of mainland Ireland, making it the most southerly point of Ireland. Many notable islands lie off Cork, including Bere, Great Island, Sherkin, and Cape Clear. With an estimated 1,199 km (745 mi) of coastline, Cork is one of three counties which claims to have the longest coastline in Ireland, alongside Mayo and Donegal.[22][23][24] Cork is also one of just three counties to border two bodies of water – the Celtic Sea to the south and the Atlantic Ocean to the west. Cork marks the end of the Wild Atlantic Way, the tourism trail from County Donegal's Inishowen Peninsula to Kinsale

| Cork Harbour (Celtic Sea) | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sea Temperature | 11.4 °C (52.5 °F) | 10.7 °C (51.3 °F) | 10.5 °C (50.9 °F) | 12.2 °C (54.0 °F) | 12.9 °C (55.2 °F) | 15.8 °C (60.4 °F) | 18.1 °C (64.6 °F) | 17.9 °C (64.2 °F) | 17.4 °C (63.3 °F) | 16.0 °C (60.8 °F) | 13.7 °C (56.7 °F) | 12.3 °C (54.1 °F) | 14.1 °C (57.4 °F) |

| Bantry (Atlantic Ocean) | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Sea Temperature | 11.6 °C (52.9 °F) | 11.2 °C (52.2 °F) | 11.0 °C (51.8 °F) | 12.1 °C (53.8 °F) | 12.8 °C (55.0 °F) | 15.6 °C (60.1 °F) | 17.6 °C (63.7 °F) | 17.5 °C (63.5 °F) | 17.3 °C (63.1 °F) | 15.8 °C (60.4 °F) | 13.8 °C (56.8 °F) | 12.2 °C (54.0 °F) | 14.0 °C (57.2 °F) |

History

edit| Year | Pop. | ±% |

|---|---|---|

| 1600 | 21,889 | — |

| 1610 | 34,250 | +56.5% |

| 1653 | 54,250 | +58.4% |

| 1659 | 63,031 | +16.2% |

| 1821 | 730,444 | +1058.9% |

| 1831 | 810,732 | +11.0% |

| 1841 | 854,118 | +5.4% |

| 1851 | 649,308 | −24.0% |

| 1861 | 544,818 | −16.1% |

| 1871 | 517,076 | −5.1% |

| 1881 | 495,607 | −4.2% |

| 1891 | 438,432 | −11.5% |

| 1901 | 404,611 | −7.7% |

| 1911 | 392,104 | −3.1% |

| 1926 | 365,747 | −6.7% |

| 1936 | 355,957 | −2.7% |

| 1946 | 343,668 | −3.5% |

| 1951 | 341,284 | −0.7% |

| 1956 | 336,663 | −1.4% |

| 1961 | 330,443 | −1.8% |

| 1966 | 339,703 | +2.8% |

| 1971 | 352,883 | +3.9% |

| 1979 | 396,118 | +12.3% |

| 1981 | 402,465 | +1.6% |

| 1986 | 412,735 | +2.6% |

| 1991 | 410,369 | −0.6% |

| 1996 | 420,510 | +2.5% |

| 2002 | 447,829 | +6.5% |

| 2006 | 481,295 | +7.5% |

| 2011 | 519,032 | +7.8% |

| 2016 | 542,868 | +4.6% |

| 2022 | 584,156 | +7.6% |

| [27] | ||

The county is colloquially referred to as "The Rebel County", although uniquely Cork does not have an official motto. This name has 15th-century origins, but from the 20th century, the name has been more commonly attributed to the prominent role Cork played in the Irish War of Independence (1919–1921) when it was the scene of considerable fighting. In addition, it was an anti-Treaty stronghold during the Irish Civil War (1922–23). Much of what is now county Cork was once part of the Kingdom of Deas Mumhan (South Munster), anglicised as the "Desmond", ruled by the MacCarthy Mór dynasty. After the Norman invasion in the 12th century, the McCarthy clan were pushed westward into what is now West Cork and County Kerry. Dunlough Castle, standing just north of Mizen Head, is one of the oldest castles in Ireland (AD 1207). The north and east of Cork were taken by the Hiberno-Norman FitzGerald dynasty, who became the Earls of Desmond. Cork City was given an English Royal Charter in 1318 and for many centuries was an outpost for Old English culture. The Fitzgerald Desmond dynasty was destroyed in the Desmond Rebellions of 1569–1573 and 1579–1583. Much of county Cork was devastated in the fighting, particularly in the Second Desmond Rebellion. In the aftermath, much of Cork was colonised by English settlers in the Plantation of Munster. [citation needed]

In 1491 Cork played a part in the English Wars of the Roses when Perkin Warbeck, a pretender to the English throne spread the story that he was really Richard of Shrewsbury (one of the Princes in the Tower), landed in the city and tried to recruit support for a plot to overthrow King Henry VII of England. The Cork people supported Warbeck because he was Flemish and not English; Cork was the only county in Ireland to join the fight. The mayor of Cork and several important citizens went with Warbeck to England, but when the rebellion collapsed they were all captured and executed. Cork's nickname of the 'rebel county' (and Cork city's of the 'rebel city') originates in these events.[28][29]

In 1601 the decisive Battle of Kinsale took place in County Cork, which was to lead to English domination of Ireland for centuries. Kinsale had been the scene of a landing of Spanish troops to help Irish rebels in the Nine Years' War (1594–1603). When this force was defeated, the rebel hopes for victory in the war were all but ended. County Cork was officially created by a division of the older County Desmond in 1606.

In the early 17th century, the townland of Leamcon (near Schull[30]: 41, 68 ) was a pirate stronghold, and pirates traded easily in Baltimore and Whiddy Island.[30]: 54–57

In the 19th century, Cork was a centre for the Fenians and for the constitutional nationalism of the Irish Parliamentary Party, from 1910 that of the All-for-Ireland Party. The county was a hotbed of guerrilla activity during the Irish War of Independence (1919–1921). Three Cork Brigades of the Irish Republican Army operated in the county and another in the city. Prominent actions included the Kilmichael Ambush in November 1920 and the Crossbarry Ambush in March 1921. The activity of IRA flying columns, such as the one under Tom Barry in west Cork, was popularised in the Ken Loach film The Wind That Shakes The Barley. On 11 December 1920, Cork City centre was gutted by fires started by the Black and Tans in reprisal for IRA attacks. Over 300 buildings were destroyed; many other towns and villages around the county, including Fermoy, suffered a similar fate.[31]

During the Irish Civil War (1922–23), most of the IRA units in Cork sided against the Anglo-Irish Treaty. From July to August 1922 they held the city and county as part of the so-called Munster Republic. However, Cork was taken by troops of the Irish Free State in August 1922 in the Irish Free State offensive, which included both overland and seaborne attacks. For the remainder of the war, the county saw sporadic guerrilla fighting until the Anti-Treaty side called a ceasefire and dumped their arms in May 1923. Michael Collins, a key figure in the War of Independence, was born near Clonakilty and assassinated during the civil war in Béal na Bláth, both in west Cork.

Irish language

editCounty Cork has two Gaeltacht areas in which the Irish language is the primary medium of everyday speech. These are Múscraí (Muskerry) in the north of the county, especially the villages of Cill Na Martra (Kilnamartyra), Baile Bhúirne (Ballyvourney), Cúil Aodha (Coolea), Béal Átha an Ghaorthaidh (Ballingeary), and Oileán Chléire (Cape Clear Island).

There are 14,829 Irish language speakers in County Cork, with 3,660 native speakers in the Cork Gaeltacht. In addition, in 2011 there were 6,273 pupils attending the 21 Gaelscoileanna and six Gaelcholáistí all across the county.[32] According to the Irish Census 2006, there are 4,896 people in the county who identify themselves as being daily Irish speakers outside of the education system. The village of Ballingeary is a centre for Irish language tuition, with a summer school, Coláiste na Mumhan, or the College of Munster.[33]

Anthem

editThe song "The Banks of My Own Lovely Lee" is traditionally associated with the county. It is sometimes heard at GAA and other sports fixtures involving the county.[34]

Media

editSeveral media publications are printed and distributed in County Cork. These include the Irish Examiner (formerly the Cork Examiner) and its sister publication The Echo (formerly the Evening Echo). Local and regional newspapers include the Carrigdhoun, the Cork Independent, The Corkman, the Mallow Star, the Douglas Post, the East Cork Journal and The Southern Star.[35][36] Local radio stations include Cork's 96FM and dual-franchise C103, Red FM, and a number of community radio stations, such as CRY 104.0FM.[37]

Places of interest

editTourist sites include the Blarney Stone at Blarney Castle, Blarney.[38] The port of Cobh in County Cork was the point of embarkation for many Irish emigrants travelling to Australia, Canada, New Zealand, South Africa or the United States. Cobh (at the time named 'Queenstown') was the last stop of the RMS Titanic before it departed on its fated journey.

Fota Wildlife Park, on Fota Island, is also a tourist attraction.[38] Nearby is Fota House and Gardens and the Fota Golf Club and Resort; a European Tour standard golf course which hosted the Irish Open in 2001, 2002 and 2014.[39]

West Cork is known for its rugged natural environment, beaches and social atmosphere, and is a common destination for British, German, French and Dutch tourists. [citation needed]

-

St Finbar's church, Gougane Barra. 6th century site

-

Saint Fin Barre's Cathedral, Cork city. Founded in 1879 on a 7th-century site[40]

-

Timoleague Friary, West Cork. Founded 1240[41]

-

Kilcrea Friary, mid-Cork. Founded 1465[42]

Economy

editThe South-West Region, comprising counties Cork and Kerry, contributed €103.2 billion (approximately US$111.6 billion) towards the Irish GDP in 2020.[43]

The harbour area east of Cork city is home to many pharmaceutical and medical companies. Mahon Point Shopping Centre is Cork's largest, and Munster's second-largest, shopping centre; it contains over 75 stores including a retail park.[citation needed] The Golden Vale is among the most productive farmland for dairy in Ireland. The chief milk processor is Dairygold, a farmer-owned co-operative based in Mitchelstown, which processes 1.4 billion litres a year, converting the milk into cheeses and powder dairy nutrition for infant formula.[44]

Demographics

edit| Rank | City or town | Population (2022)[45] |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Cork | 224,004 |

| 2 | Carrigaline | 18,239 |

| 3 | Cobh | 14,148 |

| 4 | Midleton | 13,906 |

| 5 | Mallow | 13,456 |

| 6 | Youghal | 8,564 |

| 7 | Bandon | 8,196 |

| 8 | Fermoy | 6,720 |

| 9 | Passage West-Monkstown | 6,051 |

| 10 | Kinsale | 5,991 |

The city of Cork forms the largest urban area in the county, with a total population of 224,004 as of 2022. Cork is the second-most populous city in the Republic of Ireland, and the third-most populous city on the island of Ireland. According to 2022 census statistics, the county has 13 towns with a population of over 4,000. The county has a population density of 77.8 inhabitants per square kilometre (202/sq mi). A large percentage of the population lives in urban areas.

In the 1841 census, before the outbreak of the Great Famine, County Cork had a recorded population of 854,118.[46] By the 2022 census, Cork city and county had a combined population of 584,156 people.[47]

As of the 2022 census, ethnically the population included 78.5% White Irish people, 9.9% other White background, 1.4% Asian and 1.1% Black. In 2022, the largest religious denominations in Cork were: Catholicism (71%), Church of Ireland (2.3%), Orthodox (1.2%), and Islam (1.2%). Those stating that they had no religion accounted for 15.7% of the population in 2022.[48]

Transport

editCork's main transport is serviced from:

- Air: Cork International Airport

- Rail: Iarnród Éireann's InterCity, Commuter and Freight rail services

- Sea: Port of Cork at Cork Harbour

People

editCommon surnames in the county include Barry, Buckley, Callaghan, Connell, Connor, Crowley, Lynch, McCarthy, Murphy, O'Leary, O'Sullivan, Sheehan, Walsh, and Fitzgerald (the latter with a Norman derivation).[49][50][51]

See also

editReferences

edit- ^ "What's your Irish County? County Cork". IrishCentral.com. 14 October 2016. Archived from the original on 14 August 2016. Retrieved 21 June 2019.

- ^ Local Government Arrangements in Cork – The Report of the Cork Local Government Committee (September 2015), section 2.1

- ^ "Report of the Expert Advisory Group on Local Government Arrangements in Cork". gov.ie. Department of Housing, Local Government and Heritage. 17 May 2017. Archived from the original on 28 October 2023. Retrieved 28 October 2023.

Area (Cork County: 7,467.91 km2 / Cork City: 39.61 km2

- ^ "Census 2022 - Summary Results - FY003A- Population". 30 May 2023. Archived from the original on 25 August 2021. Retrieved 3 June 2023.

- ^ "Ireland's most popular tourist counties and attractions have been revealed". TheJournal.ie. 23 July 2017. Archived from the original on 15 October 2017. Retrieved 15 October 2017.

the southwest, comprising Cork and Kerry, has the second-largest spend by tourists [after the Dublin region]

- ^ "International Office". Archived from the original on 13 August 2021. Retrieved 3 August 2021.

- ^ Local Government Act 1991 (Regional Assemblies) (Establishment) Order 2014 (S.I. No. 573 of 2014). Signed on 16 December 2014. Statutory Instrument of the Government of Ireland. Retrieved from Irish Statute Book on 14 March 2022.

- ^ Electoral (Amendment) (Dáil Constituencies) Act 2017, Schedule (No. 39 of 2017, Schedule). Enacted on 23 December 2017. Act of the Oireachtas. Retrieved from Irish Statute Book on 10 January 2022.

- ^ European Parliament Elections (Amendment) Act 2019, s. 7: Substitution of Third Schedule to Principal Act (No. 7 of 2019, s. 7). Enacted on 12 March 2019. Act of the Oireachtas. Retrieved from Irish Statute Book on 10 January 2022.

- ^ a b Bourke et al. 2011, p. 3.

- ^ Site Management Plan.

- ^ "Placenames Database of Ireland. Retrieved January 21, 2012". Logainm.ie. 13 December 2010. Archived from the original on 8 July 2013. Retrieved 23 May 2012.

- ^ "National Forestry Inventory, Third Cycle 2017". DAFM. 17 November 2020. Archived from the original on 20 June 2021. Retrieved 30 July 2021.

- ^ Baraniuk, Chris. "What would a truly wild Ireland look like?". BBC. Archived from the original on 17 February 2021. Retrieved 18 February 2021.

- ^ C. Michael Hogan. 2009. Hooded Crow: Corvus cornix, GlobalTwitcher.com, ed, N. Stromberg Archived 26 November 2010 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Cullinane, J.P., Phycology of the South Coast of Ireland. University College Cork, 1973

- ^ "Cape Clear Island: a birdwatching bonanza". Lonely Planet. 20 September 2019. Archived from the original on 1 December 2017. Retrieved 18 November 2017.

- ^ "Cape Clear Bird Observatory". BirdWatch Ireland. Archived from the original on 19 November 2017. Retrieved 18 November 2017.

- ^ Whooley, Pádraig. "Wild waters: the lesser-known life of whales and dolphins along the Irish coastline". The Irish Times. Archived from the original on 17 November 2017. Retrieved 18 November 2017.

- ^ Fáilte Ireland. "Whale Watching & Dolphin Watching in Ireland". Wild Atlantic Way. Archived from the original on 16 October 2017. Retrieved 18 November 2017.

- ^ Jones, Calvin (23 August 2016). "How to watch whales and dolphins – whalewatching tips and advice". Ireland's Wildlife. Archived from the original on 16 October 2017. Retrieved 18 November 2017.

- ^ "Irish Coastal Habitats: A Study of Impacts on Designated Conservation Areas" (PDF). heritagecouncil.ie. Heritage Council. Archived (PDF) from the original on 3 December 2020. Retrieved 6 May 2020.

- ^ "Mayo County Council Climate Adaptation Strategy" (PDF). mayococo.ie. Mayo County Council. Archived (PDF) from the original on 28 July 2020. Retrieved 9 May 2020.

- ^ "Managing the Donegal Coast in the Twenty-first Century" (PDF). research.thea.ie. Institute of Technology, Sligo. Archived (PDF) from the original on 13 July 2021. Retrieved 13 July 2021.

- ^ "Bantry Average Sea Temperature". seatemperature.org. Archived from the original on 12 August 2021. Retrieved 12 August 2021.

- ^ "Cork Average Sea Temperature". seatemperature.org. Archived from the original on 12 August 2021. Retrieved 12 August 2021.

- ^ for post 1821 figures 1653 and 1659 figures from Civil Survey Census of those years Paper of Mr Hardinge to Royal Irish Academy March 14, 1865 Archived 20 September 2010 at the Wayback Machine For a discussion on the accuracy of pre-famine census returns see J. J. Lee "On the accuracy of the pre-famine Irish censuses" in Irish Population Economy and Society edited by JM Goldstrom and LA Clarkson (1981) p54 in and also New Developments in Irish Population History 1700–1850 by Joel Mokyr and Cormac Ó Gráda in The Economic History Review New Series Vol. 37 No. 4 (November 1984) pp. 473–488.

- ^ "If not for collins, why is it called the rebel county?". Irish Independent. 4 August 2013. Archived from the original on 5 July 2018. Retrieved 28 June 2020.

- ^ O'Shea, Joe (21 May 2019). "Why is Cork called the Rebel County?". Cork Beo. Archived from the original on 28 June 2020. Retrieved 28 June 2020.

- ^ a b Senior, Clive M. (1976). A Nation of Pirates. Newton Abbot: David & Charles. ISBN 0-7153-7264-5.

- ^ "Rebelcork.com". Rebelcork.com. Archived from the original on 2 April 2012. Retrieved 23 May 2012.

- ^ "Oideachas Trí Mheán na Gaeilge in Éirinn sa Ghalltacht 2010–2011" (PDF) (in Irish). gaelscoileanna.ie. 2011. Archived (PDF) from the original on 19 April 2012. Retrieved 9 January 2012.

- ^ English, Eoin. "Fears that country’s oldest Irish summer college in Cork may not reopen this year". Irish Examiner, 25 Jan 2024. Retrieved 26 October 2024

- ^ "Lord Mayor to promote Cork songs at schools". Cork Independent. 27 August 2009. Archived from the original on 21 August 2010. Retrieved 23 May 2012.

- ^ "Regional Newspaper Circulation". ilevel.ie. 17 July 2012. Archived from the original on 8 August 2021. Retrieved 8 August 2021.

- ^ "Media Monitoring Analysis and Evaluation Brochure". Nimms Ltd. April 2011. Archived from the original on 8 August 2021. Retrieved 8 August 2021.

- ^ "List of TV and Radio Stations". bai.ie. Broadcasting Authority of Ireland. Archived from the original on 8 August 2021. Retrieved 8 August 2021.

- ^ a b "Fota and Blarney are Cork's top attractions". The Corkman. Independent News & Media. 8 August 2013. Archived from the original on 8 August 2021. Retrieved 8 August 2021.

- ^ "History". European Tour. Archived from the original on 25 October 2022. Retrieved 25 October 2022.

- ^ Bracken & Riain-Raedel 2006, p. 47.

- ^ "Proceedings of the Royal Irish Academy: Archaeology, Celtic studies, history, linguistics and literature". The Academy, 1970. p. 93

- ^ Keohane 2020, p. 451.

- ^ "County Incomes and Regional GDP 2020". Central Statistics Office. 2020. Archived from the original on 2 July 2023. Retrieved 5 December 2023.

- ^ "Dairygold opens €85m facility at Mallow headquarters". RTÉ. 22 September 2017. Archived from the original on 17 November 2017. Retrieved 16 November 2017.

- ^ "Census 2022 Profile 1 - Population Distribution and Movement F1015 - Population". Central Statistics Office. Archived from the original on 25 August 2021. Retrieved 28 October 2023.

- ^ "Brutality of Cork's Famine years: 'I saw hovels crowded with the sick and the dying in every doorway'". Irish Examiner. 8 May 2018. Archived from the original on 12 September 2022. Retrieved 12 September 2022.

- ^ "Census 2022: Cork population increases by 7.1%". echolive.ie. 23 June 2022. Archived from the original on 12 September 2022. Retrieved 12 September 2022.

- ^ "Profile 5 Diversity, Migration, Ethnicity, Irish Travellers & Religion Cork". Census 2022. Central Statistics Office. 26 October 2023. Archived from the original on 28 October 2023. Retrieved 28 October 2023.

- ^ "Popular Cork surnames and families". Roots Ireland. Archived from the original on 26 June 2018. Retrieved 26 June 2018.

- ^ "CORK". John Grenham. Archived from the original on 26 June 2018. Retrieved 26 June 2018.

- ^ "Cork". irishgenealogy.com. Archived from the original on 6 June 2018. Retrieved 26 June 2018.

Sources

edit- Bourke, Edward; Hayden, Alan; Lynch, Ann; O'Sullivan, Michael (2011). Skellig Michael, Co. Kerry: The Monastery and South Peak: Archaeological Stratigraphic Report: Excavations 1986–2010. Dublin: Department of Culture, Heritage and the Gaeltacht. OCLC 795846647.

- Bracken, Damian; Riain-Raedel, Dagmar Ó (2006). Ireland and Europe in the Twelfth Century: Reform and Renewal. Dublin: Four Courts Press. ISBN 978-1-85182-848-7.

- Keohane, Frank (2020). Cork: City and County. Buildings of Ireland. New Haven, CT / London: Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-22487-0.

- "Skellig Michael World Heritage Site Management Plan : 2008–2018" (PDF). Department of the Environment, Heritage and Local Government. 2008. OCLC 916003677. Archived (PDF) from the original on 30 August 2017.