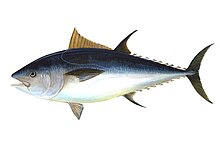

The Atlantic bluefin tuna (Thunnus thynnus) is a species of tuna in the family Scombridae. It is variously known as the northern bluefin tuna (mainly when including Pacific bluefin as a subspecies), giant bluefin tuna (for individuals exceeding 150 kg [330 lb]), and formerly as the tunny.

| Atlantic bluefin tuna | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Actinopterygii |

| Order: | Scombriformes |

| Family: | Scombridae |

| Genus: | Thunnus |

| Subgenus: | Thunnus |

| Species: | T. thynnus

|

| Binomial name | |

| Thunnus thynnus | |

| Synonyms[2] | |

|

Scomber thynnus Linnaeus, 1758 | |

Atlantic bluefins are native to both the western and eastern Atlantic Ocean, as well as the Mediterranean Sea. They have become regionally extinct in the Black Sea. The Atlantic bluefin tuna is a close relative of one of the other two bluefin tuna species, the Pacific bluefin tuna. The southern bluefin tuna, on the other hand, is more closely related to other tuna species such as yellowfin tuna and bigeye tuna, and the similarities between the southern and northern species are due to convergent evolution.[3]

Atlantic bluefin tuna have been recorded at up to 680 kg (1,500 lb) in weight, and rival the black marlin, blue marlin, and swordfish as the largest Perciformes. Throughout recorded history, the Atlantic bluefin tuna has been highly prized as a food fish. Besides their commercial value as food, the great size, speed, and power they display as predators has attracted the admiration of fishermen, writers, and scientists.

The Atlantic bluefin tuna has been the foundation of one of the world's most lucrative commercial fisheries. Medium-sized and large individuals are heavily targeted for the Japanese raw-fish market, where all bluefin species are highly prized for sushi and sashimi.

This commercial importance has led to severe overfishing. The International Commission for the Conservation of Atlantic Tunas affirmed in October 2009 that Atlantic bluefin tuna stocks had declined dramatically over the last 40 years, by 72% in the Eastern Atlantic, and by 82% in the Western Atlantic.[4] On 16 October 2009, Monaco formally recommended endangered Atlantic bluefin tuna for an Appendix I CITES listing and international trade ban. In early 2010, European officials, led by the French ecology minister, increased pressure to ban the commercial fishing of bluefin tuna internationally.[5] However, a UN proposal to protect the species from international trade was voted down (68 against, 20 for, 30 abstaining).[6] Since then, enforcement of regional fishing quotas has led to some increases in population. As of 4 September 2021[update] the Atlantic bluefin tuna was moved from the category of Endangered to the category of Least Concern on the IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. However, many regional populations are still severely depleted, including western stocks which spawn in the Gulf of Mexico.[7][8]

Most bluefins are captured commercially by professional fishermen using longlines, purse seines, assorted hook-and-line gear, heavy rods and reels, and harpoons. Recreationally, bluefins have been one of the most important big-game species sought by sports fishermen since the 1930s, particularly in the United States, but also in Canada, Spain, France, and Italy.

Taxonomy

editThe Atlantic bluefin tuna was one of the many fish species originally described by Carl Linnaeus in his landmark 1758 10th edition of Systema Naturae, where it was given the binomial name Scomber thynnus.[9]

It is most closely related to the Pacific bluefin tuna (T. orientalis) , and more distantly to the other large tunas of the genus Thunnus – the southern bluefin tuna (T. maccoyii), the bigeye tuna (T. obesus) and the yellowfin tuna (T. albacares). The southern bluefin tuna was traditionally considered the closest relatives of the two northern species, but a recent study has suggested that the morphological similarities are the result of convergent evolution, and many are adaptations for cold water habitats. [3][10] For many years, the Pacific and Atlantic bluefin tuna species were considered to be the same, or subspecies, and referred to as the "northern bluefin tuna".[10] This name occasionally gives rise to some confusion, as the longtail tuna (T. tonggol) can in Australia sometimes be known under the name "northern bluefin tuna".[11][12] This is also true in New Zealand and Fiji.

Bluefin tuna were often referred to as the common tunny, especially in the UK, Australia, and New Zealand. The name "tuna", a derivative of the Spanish atún, was widely adopted in California in the early 1900s, and has since become accepted for all tunas, including the bluefin, throughout the English-speaking world. In some languages, the red color of the bluefin's meat is included in its name, as in atún rojo (Spanish) and tonno rosso (Italian), amongst others.

Description

editThe body of the Atlantic bluefin tuna is rhomboidal in profile and robust. The head is conical and the mouth rather large. The head contains a "pineal window" that allows the fish to navigate over its multiple thousands-of-miles range.[13] Their color is dark blue above and gray below, with a gold coruscation covering the body and bright yellow caudal finlets. Bluefin tuna can be distinguished from other family members by the relatively short length of their pectoral fins. Their livers have a unique characteristic in that they are covered with blood vessels (striated). In other tunas with short pectoral fins, such vessels are either not present or present in small numbers along the edges.

Fully mature adult specimens average 2–2.5 m (6.6–8.2 ft) long and weigh around 225–250 kg (496–551 lb).[14][15] The largest recorded specimen taken under International Game Fish Association rules was caught off Nova Scotia, an area renowned for huge Atlantic bluefin, and weighed 679 kg (1,497 lb) and was 3.84 m (12.6 ft) long.[16][17] The longest contest between man and tuna fish occurred near Liverpool, Nova Scotia in 1934, when six men taking turns fought a 164–363 kilograms (361–800 lb) tuna for 62 hours.[18] Both the Smithsonian Institution and the U. S. National Marine Fisheries Service have accepted that this species can weigh up to 910 kg (2,010 lb), though further details are lacking.[15][19] Atlantic bluefin tuna reach maturity relatively quickly. In a survey that included specimens up to 2.55 m (8.4 ft) in length and 247 kg (545 lb) in weight, none was believed to be older than 15 years.[20] However, very large specimens may be up to 50 years old.[20]

The bluefin possesses enormous muscular strength, which it channels through a pair of tendons to its lunate-shaped caudal fin for propulsion. In contrast to many other fish, the body stays rigid while the tail flicks back and forth, increasing stroke efficiency.[21] It also has a very efficient circulatory system. It possesses one of the highest blood-hemoglobin concentrations among fish, which allows it to efficiently deliver oxygen to its tissues; this is combined with an exceptionally thin blood-water barrier to ensure rapid oxygen uptake.[22]

To keep its core muscles warm, which are used for power and steady swimming, the Atlantic bluefin uses countercurrent exchange to prevent heat from being lost to the surrounding water. Heat in the venous blood is efficiently transferred to the cool, oxygenated arterial blood entering a rete mirabile.[22] While all members of the tuna family are warm-blooded, the ability to thermoregulate is more highly developed in bluefin tuna than in any other fish. This allows them to seek food in the rich but chilly waters of the North Atlantic.[13]

Biology and ecology

editBluefins dive to depths of 1,006 m (3,301 ft).[23][24] The Atlantic bluefin tuna typically hunts small fish such as sardines, herring, mackerel, and eels, and invertebrates such as squid and crustaceans.[25] They exhibit opportunistic hunting in schools of fish organized by size. Their white skeletal muscle allows for large contractions which aids burst swimming to ensure prey capture.

The species is host to over 70 parasites although none have been yet described as causing harm to the species. The tetraphyllidean tapeworm Pelichnibothrium speciosum is one parasite of the species.[26] As the tapeworm's definite host is the blue shark, which does not generally seem to feed on tuna,[citation needed] the Atlantic bluefin tuna likely is a dead-end host for P. speciosum.

Atlantic bluefin tuna are eaten by a wide variety of predators. When they are newly hatched, they are eaten by other fishes that specialize on eating plankton. At that life stage, their numbers are reduced dramatically. Those that survive face a steady increase in the size of their predators. Adult Atlantic Bluefin are not eaten by anything other than the very largest billfishes, toothed whales, and some open ocean shark species.[27]

Life history

editBluefin tuna are oviparous, congregating together in large groups to spawn. Over several days, a female releases large numbers of eggs into the water where they are fertilized externally by male sperm. Female bluefins have been estimated to produce a mean of 128.5 eggs per gram of body weight, or up to 40 million eggs at a time. Eggs hatch into larvae two days after fertilization and become cannibalistic quarter-inch long fish by the end of a week. About 40% of larvae survive their first week, and about 0.1% the first year. Surviving bluefin tend to group together in schools according to size.[28]

Atlantic bluefin tuna were traditionally known to spawn in two widely separated areas. Pop-up satellite tracking results generally confirm the belief held by many scientists and fishermen that although bluefin that were spawned in each area may forage widely across the Atlantic, the vast majority return to their natal area to spawn.[29] The spawning ground of the eastern stock of Atlantic bluefin is in the western Mediterranean, particularly in the area of the Balearic Islands. The spawning ground of the western stock is in the Gulf of Mexico.[30] Because Atlantic bluefins group together in large concentrations to spawn, they are highly vulnerable to commercial fishing while spawning. This is particularly so in the Mediterranean, where the groups of spawning bluefins can be spotted from the air by light aircraft and purse seines directed to set around the schools.

In 2016, researchers suggested that a third spawning area exists in the Slope Sea, an area to the north and west of the Northeastern United States Continental Shelf. Subsequent research indicates that comparable concentrations of bluefin larvae are found in the Slope Sea and in the Gulf of Mexico.[31][32]

A number of behavioral differences have been observed between the eastern and western populations, some of which may reflect environmental conditions. For example, bluefin in the Gulf of Mexico spawn between mid-April and mid-June, when the surface water temperature is between 24 °C (75 °F) and 29 °C (85 °F), while bluefin in the Mediterranean spawn between June and August, when water is between 18 °C (65 °F) and 21 °C (70 °F).[33] In the Gulf of Mexico bluefin appear to correct for higher surface temperatures by diving, going deeper than 500 metres (1,600 ft) when entering the Gulf and staying deeper than 200 metres (660 ft) to spawn.[34]

The western and eastern populations have been thought to mature at different ages. Bluefins born in the east are thought to reach maturity a year or two earlier than those spawned in the west.[35][24] It has also been suggested that these apparent differences may reflect not-well-understood complexities of migration patterns[36] and additional spawning areas such as the Slope Sea.[35]

Human interaction

editAncient fishery

editAccording to Longo, "by the turn of the first millennium CE, a sophisticated bluefin tuna trap fishery [had] emerged. ... This trap fishery, called tonnara in Italian, madrague in French, almadraba in Spanish, and armação in Portuguese, forms an elaborate maze of nets that capture and corral bluefin tuna during their spawning season. Active for more than a thousand years, the traditional/artisanal bluefin tuna trap fishery has experienced a collapse in the Mediterranean and has struggled where it is still practiced."[37]

Commercial fishery

editAfter World War II, Japanese fishermen wanted more tuna to eat and to export for European and U.S. canning industries. They expanded their fishing range and perfected industrial long-line fishing, a practice that employs thousands of baited hooks on lines several kilometers long. In the 1970s, Japanese manufacturers developed lightweight, high-strength polymers that were spun into drift net. Though they were banned on the high seas by the early 1990s, in the 1970s, hundreds of kilometers of them were often deployed in a single night. At-sea freezing technology then allowed them to bring frozen sushi-ready tuna from the farthest oceans to market after as long as a year.[13]

The initial target was yellowfin tuna. Japanese did not value bluefin before the 1960s. By the late 1960s, sportfishing for giant bluefin tuna was burgeoning off Nova Scotia, New England, and Long Island. North Americans, too, had little appetite for bluefins, usually discarding them after taking a picture. The bluefin sport fishing rise, however, coincided with Japan's export boom. In the 1960s and '70s, cargo planes were returning to Japan empty. A Japanese entrepreneur realized he could buy New England and Canadian bluefins cheaply, and started filling Japan-bound holds with tuna. Exposure to beef and other fatty meats during the U.S. occupation following World War Two had prepared the Japanese palate for bluefin's fatty belly (otoro). The Atlantic bluefin was the biggest and the favorite. The appreciation rebounded across the Pacific when Americans started to eat raw fish in the late 1970s.[13]

Prior to the 1960s, Atlantic bluefin fisheries were relatively small scale, and populations remained stable. Although some local stocks, such as those in the North Sea, were damaged by unrestricted commercial fishing, other populations were not at risk. However, in the 1960s, purse seiners catching fish for the canned tuna market in United States coastal waters removed huge numbers of juvenile and young Western Atlantic bluefins, taking out several entire-year classes. Mediterranean fisheries have historically been poorly regulated and catches under-reported, with French, Spanish, and Italian fishermen competing with North African nations for a diminishing population.[citation needed] The migratory habits of tuna complicate the task of regulating the fishery, because they spend time in the national waters of multiple countries, as well as the open ocean outside of any national jurisdiction.[13]

Aquaculture

editTuna ranching began as early as the 1970s. Canadian fishermen in St Mary's Bay captured young fish and raised them in pens. In captivity, they grow to reach hundreds of kilos, eventually fetching premium prices in Japan. Ranching enables ranchers to exploit the unpredictable supply of wild-caught fish. Ranches across the Mediterranean and off South Australia grow bluefins offshore. According to OECD statistics, 35 thousand tons have been produced in 2018 with Japan accounting for about 50% of it, followed by Australia, Mexico, Spain and Turkey with smaller amounts.[39] Large proportions of juvenile and young Mediterranean fish are taken to be grown on tuna farms. Because the tuna are taken from the wild to the pens before they are old enough to reproduce, ranching is one of the most serious threats to the species.[citation needed] The slow growth and late sexual maturity of bluefin tuna compound its problems. The Atlantic population has declined by nearly 90% since the 1970s.[40]

In Europe and Australia, scientists have used light-manipulation technology and time-release hormone implants to bring about the first large-scale captive spawning of Atlantic and southern bluefins.[13] The technology involves implanting gonadotropin-releasing hormone in the fish to stimulate fertile egg production and may push the fish to reach sexual maturity at younger ages.[41]

However, since bluefins require so much food per unit of weight gained, up to 10 times that of salmon, if bluefins were to be farmed at the same scale as 21st-century salmon farming, many of their prey species might become depleted if farmed bluefin were fed the same diet as their wild counterparts. As of 2010, 30 million tonnes of small forage fish were removed from the oceans yearly, the majority to feed farmed fish.[13]

Market entry by many North African Mediterranean countries, such as Tunisia and Libya in the 1990s, along with the increasingly widespread practice of tuna farming in the Mediterranean and other areas, such as southern Australia (for southern bluefin tuna), depressed prices. One result is that fishermen must now catch up to twice as many fish to maintain their revenues.[citation needed] The Atlantic bluefin is endangered.

Threats

editGlobal appetite for fish is the predominant threat to Atlantic bluefin. Overfishing continues despite repeated warnings of the current precipitous decline. Bluefin aquaculture, which arose in response to declining wild stocks, has yet to achieve a sustainability, in part because it predominantly relies on harvesting and ranching juveniles rather than captive breeding.

The 2010 Deepwater Horizon oil spill released an estimated 4.9 million barrels of crude oil into the Gulf of Mexico during the spawning season of the Atlantic bluefin tuna. The oil is estimated to have affected roughly 3.1 million square miles, including more than 5 percent of the tuna habitat in the U.S. Exclusive Economic Zone. The spill occurred at a peak time for the fertilization of eggs and the development of larval bluefin tuna. Resulting short and long-term impacts on populations of Atlantic bluefin tuna and other pelagic species are difficult to determine, in part due to limitations in monitoring ability.[42] [43][44] Nonetheless, a number of lethal and sublethal impacts have been documented, including pericardial edema, defective cardiac function and cardiac abnormalities.[45]

Conservation

editFisheries management organizations

editIn 2007, researchers from the International Commission for the Conservation of Atlantic Tunas (ICCAT) — the regulators of Atlantic bluefin fishing—recommended a global quota of 15,000 tonnes to maintain current stocks or 10,000 tonnes to allow the fisheries recovery. ICCAT then chose a quota of 36,000 tonnes, but surveys indicated that up to 60,000 tonnes were actually being taken (a third of the total remaining stocks) and the limit was reduced to 22,500 tonnes. Their scientists now say that 7,500 tonnes are the sustainable limit. In November 2009, ICCAT set the 2010 quota at 13,500 tonnes and said that if stocks were not rebuilt by 2022, it would consider closing some areas.[6]

On 18 March 2010, the United Nations rejected a U.S.-backed effort to impose a total ban on Atlantic bluefin tuna fishing and trading.[46] The Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species (CITES) vote was 68 to 20 with 30 European abstentions. The leading opponent, Japan, claimed that ICCAT was the proper regulatory body.[6]

In 2011, the USA's National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) decided not to list the Atlantic bluefin tuna as an endangered species. NOAA officials said that the more stringent international fishing rules created in November 2010 would be enough for the Atlantic bluefin tuna to recover. NOAA agreed to reconsider the species' endangered status in 2013.[47] It was made a National Marine Fisheries Service species of concern, one of those species about which the U.S. government has some concerns regarding status and threats, but for which insufficient information is available to indicate a need to list the species under the U.S. Endangered Species Act.[48]

In November 2012, 48 countries meeting in Morocco for the International Commission for the Conservation of Atlantic Tunas voted to keep strict fishing limits, saying the species' population is still fragile. The quota will rise only slightly, from 12,900 metric tons a year to 13,500.[49] The decision was reviewed in November 2014, resulting in higher allowances listed below.

The latest stock assessment for Atlantic bluefin tuna reflected an improvement in the status for both western and eastern Atlantic/Mediterranean stocks. The Commission adopted new management measures that are within the range of scientific advice, are consistent with the respective rebuilding plans, and allow for continued stock growth. For the western stock, the TAC of 2,000 mt annually for 2015 and 2016 will provide for continued growth in spawning stock biomass and allow the strong 2003 year-class to continue to enhance the productivity of the stock. The TAC for the eastern Atlantic/Mediterranean stock was set at 16,142 t for 2015; 19,296 t for 2016; and 23,155 t for 2017.[50]

In 2020, the UK government recognized the increasing incidence of bluefin tuna in UK waters in recent years and is funding ongoing research to understand the ecology of the species and devise an approach to its management.[51][52]

Other organizations

editIn 2010, Greenpeace International added the northern bluefin tuna to its seafood red list.[53] As of January 2022, the bluefin tuna remains on the list.[54]

In the summer of 2011, the Sea Shepherd Conservation Society led a campaign against supposedly illegal bluefin tuna fishing off the coast of Libya, which was under Muammar Gaddafi's regime at the time. The fishermen retaliated against Sea Shepherd's intervention by throwing various small metal pieces at the crew. Nobody was injured due to the other side's actions during the conflict.[55]

In November 2011, food critic Eric Asimov of The New York Times criticized the top-ranked New York City restaurant Sushi Yasuda for offering bluefin tuna on their menu, arguing that drawing from such a threatened fishery constituted an unjustifiable risk to bluefins, and to the future of culinary traditions that depend on the species.[56]

The bluefin species are listed by the Monterey Bay Aquarium on its Seafood Watch list and pocket guides as fish to avoid due to overfishing.[57]

Cuisine

editAtlantic bluefin tuna is one of the most highly prized fish used in Japanese raw fish dishes. About 80% of the caught Atlantic and Pacific bluefin tunas are consumed in Japan.[58] Bluefin tuna sashimi is a particular delicacy in Japan. For example, an Atlantic bluefin caught off eastern United States sold for US$247,000 at the Tsukiji fish market in Tokyo in 2008.[59] This high price is considerably less than the highest prices paid for Pacific bluefin.[58][59] Prices were highest in the late 1970s and 1980s.[60]

Japanese began eating tuna sushi in the 1840s, when a large catch came into Edo [old Tokyo] one season. A chef marinated a few pieces in soy sauce and served it as nigiri sushi. At that time, these fish were nicknamed shibi — "four days" — because chefs would bury them for four days to mellow their bloody taste.[13]

Originally, fish with red flesh were looked down on in Japan as a low-class food, and white fish were much preferred. ... Fish with red flesh tended to spoil quickly and develop a noticeable stench, so in the days before refrigeration, the Japanese aristocracy despised them, and this attitude was adopted by the citizens of Edo. – Michiyo Murata[13]

By the 1930s, tuna sushi was commonplace in Japan.

See also

editReferences

edit- ^ Collette, B.B.; Boustany, A.; Fox, W.; Graves, J.; Juan Jorda, M.; Restrepo, V. (2021). "Thunnus thynnus". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2021: e.T21860A46913402. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2021-2.RLTS.T21860A46913402.en. Retrieved 19 November 2021.

- ^ "Thunnus thynnus (Linnaeus, 1758)". Integrated Taxonomic Information System. Retrieved 9 December 2012.

- ^ a b Ciezarek, Adam; Osborne, Owen; Shipley, Oliver; Brooks, Edward James (October 2018). "Phylotranscriptomic Insights into the Diversification of Endothermic Thunnus Tunas". Molecular Biology and Evolution. 36 (1): 84–96. doi:10.1093/molbev/msy198. PMC 6340463. PMID 30364966.

- ^ "Endangered Atlantic bluefin tuna formally recommended for international trade ban". October 2009. Retrieved 17 October 2009.

- ^ Jolly, David (3 February 2010). "Europe Leans Toward Bluefin Trade Ban". The New York Times.

- ^ a b c Jolly, David; Broder, John M. (18 March 2010). "U.N. Rejects Export Ban on Atlantic Bluefin Tuna". New York Times. Retrieved 19 March 2010.

- ^ Collette, B.B.; Wells, D. & Abad-Uribarren, A. (2015). "Thunnus thynnus (Gulf of Mexico assessment)". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2015: e.T21860A76599358. Retrieved 23 August 2023.

- ^ "Tuna species recovering despite growing pressures on marine life - IUCN Red List". IUCN. 4 September 2021. Retrieved 6 June 2022.

- ^ Linnaeus, Carl (1758). Systema Naturae per Regna Tria Naturae, Secundum Classes, Ordines, Genera, Species, cum Characteribus, Differentiis, Synonymis, Locis (in Latin). Vol. I (10th revised ed.). Holmiae: (Laurentii Salvii). p. 297.

- ^ a b Collette, B.B. (1999). Mackerels, molecules, and morphology. In: Proceedings of the 5th Indo-Pacific Fish Conference, Noumea. pp. 149–164

- ^ Hutchins, B. & Swainston, R. (1986). Sea Fishes of Southern Australia. pp. 104 & 141. ISBN 1-86252-661-3

- ^ Allen, G. (1999). Marine Fishes of Tropical Australia and South-East Asia. p. 230. ISBN 0-7309-8363-3

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Greenberg, Paul (27 June 2010). "Tuna's End". The New York Times. p. 28.

- ^ The Atlantic Bluefin Tuna Archived 1 June 2012 at the Wayback Machine. Outdoor.se (31 July 1926). Retrieved on 2013-05-04.

- ^ a b Atlantic Bluefin Tuna (Thunnus thynnus). Nmfs.noaa.gov. Retrieved on 4 May 2013.

- ^ "Tuna, bluefin (Thunnus thynnus) - All-Tackle World Records". igfa.org. Retrieved 5 January 2023.

- ^ Collette, Bruce B.; Nauen, Cornelia E. (1983). Fao Species Catalogue. Vol. 2 Scombrids of the World: An Annotated and Illustrated Catalogue of Tunas, Mackerels, Bonitos, and Related Species Known to Date (PDF). Rome: UNDP/FAO. p. 92.

- ^ Johnston, Gordon (1973). It Happened in Canada. Scholastic. ASIN B000VUPG1M.

- ^ Burnie D and Wilson DE (Eds.), Animal: The Definitive Visual Guide to the World's Wildlife. DK Adult (2005), ISBN 0789477645

- ^ a b Santamaria, N.; Bello, G.; Corriero, A.; Deflorio, M.; Vassallo-Agius, R.; Bök, T. & Metrio, G. De (2009). "Age and growth of Atlantic bluefin tuna, Thunnus thynnus (Osteichthyes: Thunnidae) in the Mediterranean Sea". Journal of Applied Ichthyology. 25 (1): 38. Bibcode:2009JApIc..25...38S. doi:10.1111/j.1439-0426.2009.01191.x.

- ^ Piper, Ross (2007), Extraordinary Animals: An Encyclopedia of Curious and Unusual Animals, Greenwood Press.

- ^ a b Hill, Richard W.; Wyse, Gordon A.; Anderson, Margaret (2004). Animal Physiology. Sinauer Associates, Inc. ISBN 0-87893-315-8.

- ^ {Ellis (2003) The Empty Ocean, p32}

- ^ a b Block, B. A.; Dewar, H; Blackwell, S. B.; Williams, T. D.; Prince, E. D.; Farwell, C. J.; Boustany, A; Teo, S. L.; Seitz, A; Walli, A; Fudge, D (2001). "Migratory Movements, Depth Preferences, and Thermal Biology of Atlantic Bluefin Tuna" (PDF). Science. 293 (5533): 1310–4. Bibcode:2001Sci...293.1310B. doi:10.1126/science.1061197. PMID 11509729. S2CID 32126319.

- ^ "Thunnus thynnus (Horse mackerel)". Animal Diversity Web.

- ^ Scholz, T. Š. (1998). "Taxonomic status of Pelichnibothrium speciosum Monticelli, 1889 (Cestoda: Tetraphyllidea), a mysterious parasite of Alepisaurus ferox Lowe (Teleostei: Alepisauridae) and Prionace glauca (L.) (Euselachii: Carcharinidae)". Systematic Parasitology. 41: 1–8. doi:10.1023/A:1006091102174. S2CID 33831101.

- ^ "Atlantic Bluefin Tuna". Oceana. Retrieved 27 March 2023.

- ^ Whynott, Douglas (30 June 1996). Giant Bluefin. Macmillan. ISBN 978-0-86547-497-0. Retrieved 6 June 2022.

- ^ Würtz, Maurizio (2010). Mediterranean Pelagic Habitat: Oceanographic and Biological Processes, an Overview. IUCN. ISBN 978-2-8317-1242-0. Retrieved 6 June 2022.

- ^ Cermeño, Pablo; Quílez-Badia, Gemma; Ospina-Alvarez, Andrés; Sainz-Trápaga, Susana; Boustany, Andre M.; Seitz, Andy C.; Tudela, Sergi; Block, Barbara A. (11 February 2015). "Electronic Tagging of Atlantic Bluefin Tuna (Thunnus thynnus, L.) Reveals Habitat Use and Behaviors in the Mediterranean Sea". PLOS ONE. 10 (2): e0116638. Bibcode:2015PLoSO..1016638C. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0116638. PMC 4324982. PMID 25671316.

- ^ Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution (4 March 2022). "Evidence bolsters classification of a major spawning ground for Atlantic bluefin tuna off the northeast U.S." phys.org. Retrieved 7 June 2022.

- ^ "Searching for Atlantic bluefin tuna larvae and more in the Slope Sea". Field Fresh. 15 June 2017. Retrieved 7 June 2022.

- ^ "Atlantic Bluefin Tuna Thunnus thynnus". Travel portal. Retrieved 7 June 2022.

- ^ Pain, Stephanie (31 May 2022). "Call of the deep". Knowable Magazine. Annual Reviews. doi:10.1146/knowable-052622-3. Retrieved 7 June 2022.

- ^ a b Richardson, David E.; Marancik, Katrin E.; Guyon, Jeffrey R.; Lutcavage, Molly E.; Galuardi, Benjamin; Lam, Chi Hin; Walsh, Harvey J.; Wildes, Sharon; Yates, Douglas A.; Hare, Jonathan A. (7 March 2016). "Discovery of a spawning ground reveals diverse migration strategies in Atlantic bluefin tuna (Thunnus thynnus)". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 113 (12): 3299–3304. Bibcode:2016PNAS..113.3299R. doi:10.1073/pnas.1525636113. ISSN 0027-8424. PMC 4812764. PMID 26951668.

- ^ Shwartz, Mark; Peterson, Ken (25 April 2005). "Migration study concludes that sweeping management changes are needed to protect Atlantic bluefin tuna". Stanford News Release. Retrieved 7 June 2022.

- ^ Longo, Stefano B. (26 August 2011). "Global Sushi: The Political Economy of the Mediterranian Bluefin Tuna Fishery in the Modern Era". Journal of World-Systems Research. 17 (2): 403–427. doi:10.5195/jwsr.2011.422.

- ^ "Fisheries and Aquaculture - Global Production". Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO). Retrieved 9 December 2024.

- ^ "OECD stats on aquaculture". OECD. Retrieved 28 September 2020.

- ^ "Bluefin Tuna". Monterey Bay Aquarium. Archived from the original on 14 October 2007. Retrieved 2 February 2012.

- ^ "Breeding the Overfished Bluefin Tuna". LiveScience. 17 March 2008. Retrieved 13 February 2012.

- ^ "Deepwater Horizon oil spill impacted bluefin tuna spawning habitat in Gulf of Mexico, Stanford and NOAA researchers find". Stanford News. 30 September 2016. Retrieved 6 June 2022.

- ^ Hazen, Elliott L.; Carlisle, Aaron B.; Wilson, Steven G.; Ganong, James E.; Castleton, Michael R.; Schallert, Robert J.; Stokesbury, Michael J. W.; Bograd, Steven J.; Block, Barbara A. (22 September 2016). "Quantifying overlap between the Deepwater Horizon oil spill and predicted bluefin tuna spawning habitat in the Gulf of Mexico". Scientific Reports. 6 (1): 33824. Bibcode:2016NatSR...633824H. doi:10.1038/srep33824. ISSN 2045-2322. PMC 5031980. PMID 27654709. Retrieved 6 June 2022.

- ^ Muhling, B.A.; Roffer, M.A.; Lamkin, J.T.; Ingram, G.W.; Upton, M.A.; Gawlikowski, G.; Muller-Karger, F.; Habtes, S.; Richards, W.J. (April 2012). "Overlap between Atlantic bluefin tuna spawning grounds and observed Deepwater Horizon surface oil in the northern Gulf of Mexico" (PDF). Marine Pollution Bulletin. 64 (4): 679–687. Bibcode:2012MarPB..64..679M. doi:10.1016/j.marpolbul.2012.01.034. PMID 22330074. Retrieved 7 June 2022.

- ^ Murawski, Steven A.; Grosell, Martin; Smith, Cynthia; Sutton, Tracey; Halanych, Kenneth M.; Shaw, Richard F.; Wilson, Charles A. (2021). "Impacts of Petroleum, Petroleum Components, and Dispersants on Organisms and Populations". Oceanography. 34 (1): 136–151. doi:10.5670/oceanog.2021.122. ISSN 1042-8275. JSTOR 27020066. S2CID 236766859.

- ^ Black, Richard (18 March 2010). "Bluefin tuna ban proposal meets rejection". BBC News. Archived from the original on 25 March 2010. Retrieved 13 April 2010.

- ^ Harris, Richard (27 May 2011). "Sorry, Charlie! Better Luck Next Time Getting Endangered Species Status". NPR. Retrieved 30 May 2011.

- ^ Species of Concern NOAA

- ^ "Bluefin tuna quotas remain in place". 3 News NZ. 20 November 2012.

- ^ "Highlights of the 2014 International Commission for the Conservation of Atlantic Tunas (ICCAT) Meeting" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 8 May 2017. Retrieved 29 December 2017.

- ^ Messenger, Steffan (1 April 2021). "Giant bluefin tuna return in Wales a 'massive opportunity'". BBC News. Retrieved 1 April 2021.

- ^ "GOV.UK: Bluefin tuna in the UK". Retrieved 1 April 2021.

- ^ "Greenpeace International Seafood Red list". Greenpeace.org. 17 March 2003. Archived from the original on 10 April 2010. Retrieved 13 April 2010.

- ^ "Red List Fish". Greenpeace USA. 15 July 2015. Retrieved 18 January 2022.

- ^ Operation Blue Rage 2011 Archived 2 November 2013 at the Wayback Machine. Seashepherd.org. Retrieved on 1 May 2015.

- ^ Asimov, Eric (15 November 2011). "Sushi Yasuda — NYC". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 17 November 2011. Retrieved 30 January 2013.

- ^ Tuna, Bluefin – Seafood Watch. Montereybayaquarium.org. Retrieved on 4 May 2013.

- ^ a b Washington Post (5 January 2011). Swank sushi: Bluefin tuna nets $736,000 at Tokyo auction, easily beating old record.[dead link] Accessed 6 January 2011

- ^ a b NBC News (1 January 2009). Premium tuna fetches $100,000 at auction. Accessed 6 January 2011

- ^ "Once Robust, Bluefin Tuna Fishery is in Economic Freefall".

Further reading

edit- Clover, Charles (2004). The End of the Line: How Overfishing Is Changing the World and What We Eat. Ebury Press, London. ISBN 0-09-189780-7

- Hogan, C. Michael. (2010). "Overfishing". Encyclopedia of Earth. National Council for Science and the Environment. eds. Sidney Draggan & C. Cleveland. Washington DC.

- Newlands, Nathaniel K. (2002). "Shoaling dynamics and abundance estimation: Atlantic bluefin tuna (Thunnus thynnus)". PhD thesis, Resource Management and Environmental Studies/Fisheries Centre, University of British Columbia, Vancouver, Canada. 602pp,

- Newlands, N. K.; Lutcavage, M. & Pitcher, T. (October 2006). "Atlantic Bluefin Tuna in the Gulf of Maine, I: Estimation of Seasonal Abundance Accounting for Movement, School and School-Aggregation Behaviour". Environmental Biology of Fishes. 77 (2).

- Newlands, N. K.; Lutcavage, M. & Pitcher, T. (December 2007). "Atlantic bluefin tuna in the Gulf of Maine, II: precision of sampling designs in estimating seasonal abundance accounting for tuna behaviour". Environmental Biology of Fishes. 80 (4): 405–420.

- Newlands, Nathaniel K.; Lutcavage, Molly E. & Pitcher, Tony J. (April 2004). "Analysis of foraging movements of Atlantic bluefin tuna (Thunnus thynnus): individuals switch between two modes of search behaviour". Population Ecology. 46 (1): 39–53.

- Newlands, Nathaniel K.; Porcelli, Tracy A. (2008). "Measurement of the size, shape and structure of Atlantic bluefin tuna schools in the open ocean". Fisheries Research. 91 (1): 42–55.

- Safina, C. (1993). "Bluefin Tuna in the West Atlantic: Negligent Management, and the Making of an Endangered Species". Conservation Biology. 7: 229–234.

- Safina, C. (1998). Song For The Blue Ocean. Henry Holt Co. New York.

- Safina, C. & Klinger, D. (2008). "Collapse of Bluefin Tuna in the Western Atlantic". Conservation Biology. 22: 243–246.

- Froese, Rainer; Pauly, Daniel (eds.). "Thunnus thynnus". FishBase. January 2006 version.

External links

edit- Media related to Thunnus thynnus at Wikimedia Commons

- Bye bye bluefin: Managed to death – The Economist. 30 October 2008. Retrieved 6 February 2009.

- Bluefin Tuna at Seafood Watch

- Tuna at Greenpeace

- MarineBio article on tuna at MarineBio (archived 3 July 2012)

- Bluefin tuna and Sushi (archived 17 July 2011)

- brochure on bluefin tuna tagging at Tag-a-Giant Foundation (PDF; archived 3l2 March 2012)