This article has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these messages)

|

The Greek tortoise (Testudo graeca), also known commonly as the spur-thighed tortoise[1] or Moorish tortoise,[3] is a species of tortoise in the family Testudinidae. Testudo graeca is one of five species of Mediterranean tortoises (genera Testudo and Agrionemys). The other four species are Hermann's tortoise (T. hermanni), the Egyptian tortoise (T. kleinmanni), the marginated tortoise (T. marginata), and the Russian tortoise (A. horsfieldii). The Greek tortoise is a very long-lived animal, achieving a lifespan upwards of 125 years, with some unverified reports up to 200 years.[4] It has the largest known genome of all reptiles.[5]

| Greek tortoise Temporal range: Possible Late Miocene record

| |

|---|---|

| |

| T. g. nabeulensis male in Tunisia | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Reptilia |

| Order: | Testudines |

| Suborder: | Cryptodira |

| Superfamily: | Testudinoidea |

| Family: | Testudinidae |

| Genus: | Testudo |

| Species: | T. graeca

|

| Binomial name | |

| Testudo graeca | |

| |

| Note allopatric ranges of "Maghreb" (T. g. graeca) and "Greek" (T. g. ibera) populations | |

| Synonyms[2] | |

|

List

| |

Geographic range

editThe Greek tortoise's geographic range includes North Africa, Southern Europe, and Southwest Asia. It is prevalent in the Black Sea coast of the Caucasus (from Anapa, Russia, to Sukhumi, Abkhazia, Georgia, to the south), as well as in other regions of Georgia, Armenia, Iran, and Azerbaijan.

Evolution

editThe oldest known definitive fossil is from the Early Pliocene of Greece,[6] but specimens referred to as Testudo cf. graeca are known from the Late and Middle Miocene in Greece and Turkey.[7][8]

Characteristics

editThe Greek tortoise (T. g. ibera) is often confused with Hermann's tortoise (T. hermanni ). However, notable differences enable them to be distinguished.

| Greek tortoise | Hermann's tortoise |

|---|---|

| Large symmetrical markings on the top of the head | Only small scales on the head |

| Large scales on the front legs | Small scales on the front legs |

| Undivided supracaudal scute over the tail | Supracaudal scute almost always divided |

| Notable spurs on each thigh | No spurs |

| Isolated flecks on the spine and rib plates | Isolated flecks only on the spinal plates |

| Dark central fleck on the underside | Two black bands on the underside |

| Shell somewhat oblong rectangular | Oval shell shape |

| Widely stretched spinal plates | Small spinal plates |

| Movable posterior plates on underside | Fixed plates on underside |

| No tail spur | Tail bears a spur at the tip |

Subspecies

editThe division of the Greek tortoise into subspecies is difficult and confusing. Given its huge range over three continents, the various terrains, climates, and biotopes have produced a huge number of varieties, with new subspecies constantly being discovered. As of 2023, at least 20 subspecies have been published, of which the following 12 are recognized as being valid.[9]

- T. g. graeca Linnaeus, 1758 – northern Africa, southern Spain

- T. g. soussensis Pieh, 2000 – southern Morocco

- T. g. marokkensis Pieh & Perälä, 2004 – northern Morocco

- T. g. nabeulensis Highfield, 1990 – Tunisian tortoise, Tunisia

- T. g. cyrenaica Pieh & Perälä, 2002 – Libya

- T. g. ibera Pallas, 1814 – Turkey

- T. g. armeniaca Chkhikvadze & Bakradse, 1991 – Armenian tortoise, Armenia

- T. g. buxtoni Boulenger, 1921 – Caspian Sea

- T. g. terrestris Forskål, 1775 – Israel, Jordan, Lebanon

- T. g. zarudnyi Nikolsky, 1896 – Azerbaijan, Iran

- T. g. whitei Bennett in White, 1836 – Algeria

- T. g. perses Perälä, 2002 – Turkey, Iran, Iraq

This incomplete listing shows the problems in the division of the species into subspecies. The differences in form are primarily in size and weight, as well as coloration, which ranges from dark brown to bright yellow, and the types of flecks, ranging from solid colors to many spots. Also, the bending-up of the edges of their carapaces ranges from minimal to pronounced. So as not to become lost in the number of subspecies, recently, a few tortoises previously classified as T. graeca have been assigned to different species, or even different genera.

The genetic richness of T. graeca is also shown in its crossbreeding. Tortoises of different form groups often mate, producing offspring with widely differing shapes and color. Perhaps the best means of identification for the future is simply the place of origin.

The smallest, and perhaps the prettiest, of the subspecies, is the Tunisian tortoise. It has a particularly bright and striking coloration. However, these are also the most sensitive tortoises of the species, so they cannot be kept outdoors in temperate climates, as cold and rainy summers quickly cause the animals to become ill. They are also incapable of long hibernation.

At the other extreme, animals from northeastern Turkey are very robust, such as Hermann's tortoise. The largest specimens come from Bulgaria. Specimens of 7 kg (15 lb) have been reported. In comparison, the Tunisian tortoise has a maximum weight of 0.7 kg (1.5 lb). T. graeca is also closely related to the marginated tortoise (T. marginata). The two species can interbreed, producing offspring capable of reproduction.

-

in Greece

-

T. g. ibera in Turkey

-

T. g. ibera, 4 years

-

juvenile T. g. nabeulensis in Tunisia

Sexing

editMales of T. graeca differ from females in six main points. Firstly, they are generally smaller. Their tails are longer than females and taper to a point evenly, and the cloacal opening is farther from the base of the tail. The underside is somewhat curved, while females have a flat shell on the underside. The rear portion of a male's carapace is wider than it is long. Finally, the posterior plates of the carapace often flange outward.

Behavior

editHibernation

editTestudo graeca hibernates during cold months, emerging as early as February in hot coastal areas. Individual tortoises may emerge during warm days even during winter.[3]

Mating and reproduction

editIn T. graeca, immediately after waking from hibernation, the mating instinct starts up. The males follow the females with great interest, encircling them, biting them in the limbs, ramming them, and trying to mount them. During copulation, the male opens his mouth, showing his red tongue and making squeaking sounds.

During mating, the female stays still, bracing herself with her front legs, moving the front part of her body to the left and right in the same rhythm as the male's cries. One successful mating will allow the female to lay eggs multiple times. When breeding in captivity, the pairs of females and males must be kept separate. If multiple males are in a pen, one takes on a dominant role and will try to mate with the other males in the pen. If more males than females are in a pen, the males might kill each other to mate with the females.

One or two weeks before egg laying, the animals become notably agitated, moving around to smell and dig in the soil, even tasting it, before choosing the ideal spot to lay the eggs. One or two days before egg laying, the female takes on an aggressive, dominant behavior, mounting another animal as for copulation and making the same squeaking sound the male produces during copulation. The purpose of this behavior is to produce respect in the tortoise community so that the female will not be disturbed by the others during egg laying. Further details of egg-laying behavior are the same as those detailed for the marginated tortoise.

Trade

editThe Greek tortoise is commonly traded as a pet in source countries such as Morocco and Spain, despite the illegality of this trade.[10][11][12] This can lead to an unsustainable removal of wild individuals for the local pet trade and for export. Also, welfare concerns exist with this trade, as the animals are not properly housed when being sold, causing a high rate of mortality in captivity.[13]

Food

editIn captivity, the Greek tortoise loves dandelion leaves and other leafy plants. However, although they also enjoy eating lettuce, it is not recommended to them due to having a lack of nutrients that the tortoises need to survive.[14]

See also

editReferences

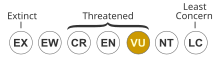

edit- ^ a b Tortoise.; Freshwater Turtle Specialist Group (1996). "Testudo graeca". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 1996: e.T21646A9305693. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.1996.RLTS.T21646A9305693.en. Retrieved 19 November 2021.

- ^ Fritz, Uwe; Havaš, Peter (2007). "Checklist of Chelonians of the World" (PDF). Vertebrate Zoology. 57 (2): 296–300. doi:10.3897/vz.57.e30895. ISSN 1864-5755. S2CID 87809001. Archived (PDF) from the original on 1 May 2011. Retrieved 29 May 2012.

- ^ a b Pritchard, Dr. Peter C. H. (1979). Encyclopedia of Turtles. Neptune, New Jersey: T. F. H. Publications. ISBN 0-87666-918-6.

- ^ "Testudo graeca". The Moirai – Aging Research. 12 September 2016. Archived from the original on 13 September 2018. Retrieved 13 December 2016.

- ^ Did Lizards Follow Unique Pathways in Sex Chromosome Evolution?

- ^ Vlachos E (2015). "The Fossil Chelonians of Greece. Systematics – Evolution – Stratigraphy – Palaeoecology". Scientific Annals of the School of Geology, Aristotle University of Thessaloniki, Greece. 173: 1–479.

- ^ Vlachos E, Tsoukala E (2014). "Testudo cf. graeca from the new Late Miocene locality of Platania (Drama basin, N. Greece) and a reappraisal of previously published specimens". Bulletin of the Geological Society of Greece. 48: 27–40. doi:10.12681/bgsg.11046.

- ^ Staesche K, Karl HV, Staesche U (2007). "Fossile Schildkroten aus der Turkei". Fossile Schildkroten aus Drei Kontinenten. 98: 91–149.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Genus Testudo at The Reptile Database www.reptile-database.org.

- ^ Pérez, Irene; Tenza, Alicia; Anadón, José Daniel; Martínez-Fernández, Julia; Pedreño, Andrés; Giménez, Andrés (2012). "Exurban sprawl increases the extinction probability of a threatened tortoise due to pet collections". Ecological Modelling. 245: 19–30. Bibcode:2012EcMod.245...19P. doi:10.1016/j.ecolmodel.2012.03.016. hdl:10261/67281.

- ^ Bergin, Daniel; Nijman, Vincent (2014). "Open, Unregulated Trade in Wildlife in Morocco's Markets, TRAFFIC Bulletin". Retrieved 23 March 2015.

- ^ Nijman, V; Bergin, D (2017). "Trade in spur-Thighed tortoises Testudo graeca in Morocco: Volumes, value and variation between markets". Amphibia-Reptilia. 38 (3): 275–287. doi:10.1163/15685381-00003109.

- ^ Bergin, D.; Nijman, V. (2018). "An Assessment of Welfare Conditions in Wildlife Markets across Morocco". Journal of Applied Animal Welfare Science. 22 (3): 279–288. doi:10.1080/10888705.2018.1492408. PMID 30102072. S2CID 51967901.

- ^ "Helpfull [sic] advice for your tortoise diet". www.tortoisecentre.co.uk. Archived from the original on 29 January 2018. Retrieved 29 January 2018.