Vasil Levski[1] (Bulgarian: Васил Левски, spelled in old Bulgarian orthography as Василъ Львскій,[2] pronounced [vɐˈsiɫ ˈlɛfski]), born Vasil Ivanov Kunchev[3] (Васил Иванов Кунчев; 18 July 1837 – 18 February 1873), was a Bulgarian revolutionary who is, today, a national hero of Bulgaria. Dubbed the Apostle of Freedom, Levski ideologised and strategised a revolutionary movement to liberate Bulgaria from Ottoman rule. Levski founded the Internal Revolutionary Organisation, and sought to foment a nationwide uprising through a network of secret regional committees.

Vasil Levski | |

|---|---|

| Васил Левски | |

| |

| Born | Vasil Ivanov Kunchev 18 July 1837 |

| Died | 18 February 1873 (aged 35) |

| Cause of death | Execution by hanging |

| Resting place | Sofia, Bulgaria |

| Occupation | Revolutionary |

| Known for | Internal Revolutionary Organisation |

| Signature | |

| |

Born in the Sub-Balkan town of Karlovo to middle-class parents, Levski became an Orthodox monk before emigrating to join the two Bulgarian Legions in Serbia and other Bulgarian revolutionary groups. Abroad, he acquired the nickname Levski ("Lionlike"). After working as a teacher in Bulgarian lands, he propagated his views and developed the concept of his Bulgaria-based revolutionary organisation, an innovative idea that superseded the foreign-based detachment strategy of the past. In Romania, Levski helped institute the Bulgarian Revolutionary Central Committee, composed of Bulgarian expatriates. During his tours of Bulgaria, Levski established a wide network of insurrectionary committees. Ottoman authorities, however, captured him at an inn near Lovech and executed him by hanging in Sofia.

Levski looked beyond the act of liberation and envisioned a Bulgarian republic of ethnic and religious equality, largely reflecting the liberal ideas of the French Revolution and contemporary Western society. He said, "We will be free in complete liberty where the Bulgarian lives: in Bulgaria, Thrace, Macedonia; people of whatever ethnicity live in this heaven of ours, they will be equal in rights to the Bulgarian in everything." Levski held that all religious and ethnic groups live in a free Bulgaria enjoy equal rights.[4][5][6] He is commemorated with monuments in Bulgaria and Serbia, and numerous national institutions bear his name. In 2007, he topped a nationwide television poll as the all-time greatest Bulgarian. Today Vasil Levski is honoured by being a symbol of freedom, celebrations in his home town and sports clubs being named after him.[7]

Historical background

editThe 19th-century Ottoman Empire's economic hardships prompted its personification as the "sick man of Europe".[8] The reforms planned by the sultans faced insuperable difficulties.[9] Bulgarian nationalism gradually emerged during the mid-19th century with the economic upsurge of Bulgarian merchants and craftsmen, the development of Bulgarian-funded popular education, the struggle for an autonomous Bulgarian Church and political actions towards the formation of a separate Bulgarian state.[10] The First and Second Serbian Uprisings had laid the foundation of an autonomous Serbia during the late 1810s,[11] and Greece had been established as an independent state in 1832, in the wake of the Greek War of Independence.[12] However, support for gaining independence through an armed struggle against the Ottomans was not universal. Revolutionary sentiment was concentrated largely among the more educated and urban sectors of the populace. There was less support for an organized revolt among the peasantry and the wealthier merchants and traders, who feared that Ottoman reprisals would jeopardize economic stability and widespread rural land ownership.[13]

Biography

editEarly life, education and monkhood

editVasil Levski was born Vasil Ivanov Kunchev on 18 July 1837 in the town of Karlovo, within the Ottoman Empire's European province of Rumelia.[14] He was the namesake of his maternal uncle, Archimandrite (superior abbot) Vasil (Василий, Vasiliy).[15] Levski's parents, Ivan Kunchev and Gina Kuncheva (née Karaivanova), came from a family of clergy and craftsmen and were members of the emerging Bulgarian middle class.[16] An eminent but struggling local craftsman, Ivan Kunchev died in 1844. Levski had two younger brothers, Hristo and Petar, and an older sister, Yana;[17] another sister, Maria, died during childhood.[18]

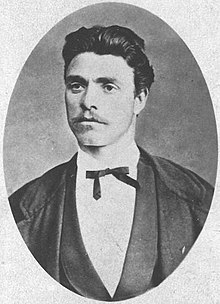

Fellow revolutionary Panayot Hitov later described the adult Levski as being of medium height and having an agile, wiry appearance—with light, greyish-blue eyes, blond hair, and a small moustache. He added that Levski abstained from smoking and drinking. Hitov's memories of Levski's appearance are supported by Levski's contemporaries, revolutionary and writer Lyuben Karavelov and teacher Ivan Furnadzhiev. The only differences are that Karavelov claimed Levski was tall rather than of medium height, while Furnadzhiev noted that his moustache was light brown and his eyes appeared hazel.[20]

Levski began his education at a school in Karlovo, studying homespun tailoring as a local craftsman's apprentice. In 1855, Levski's uncle Basil—archimandrite and envoy of the Hilandar monastery—took him to Stara Zagora, where he attended school[21] and worked as Basil's servant. Afterward, Levski joined a clerical training course.[22] On 7 December 1858, he became an Orthodox monk in the Sopot monastery[23] under the religious name Ignatius (Игнатий, Ignatiy) and was promoted in 1859 to hierodeacon,[5][24] which later inspired one of Levski's informal nicknames, The Deacon (Дякона, Dyakona).[25]

First Bulgarian Legion and educational work

editInspired by Georgi Sava Rakovski's revolutionary ideas, Levski left for the Serbian capital Belgrade during the spring[26] of 1862. In Belgrade, Rakovski had been assembling the First Bulgarian Legion, a military detachment formed by Bulgarian volunteers and revolutionary workers seeking the overthrow of Ottoman rule. Abandoning his service as a monk, Levski enlisted as a volunteer.[22][27] At the time, relations between the Serbs and their Ottoman suzerains were tense. During the Battle of Belgrade in which Turkish forces entered the city, Levski and the Legion distinguished themselves in repelling them.[28][29] Further militant conflicts in Belgrade were eventually resolved diplomatically, and the First Bulgarian Legion was disbanded under Ottoman pressure on 12 September 1862.[30] His courage during training and fighting earned him his nickname Levski ("Lionlike").[21][31][32] After the legion's disbandment, Levski joined Ilyo Voyvoda's detachment at Kragujevac, but returned to Rakovski in Belgrade after discovering that Ilyo's plans to invade Bulgaria had failed.[33]

In the spring of 1863, Levski returned to Bulgarian lands after a brief stay in Romania. His uncle Basil reported him as a rebel to the Ottoman authorities, and Levski was imprisoned in Plovdiv for three months, but released due to the help of the doctor R. Petrov and the Russian vice-consul Nayden Gerov.[34] On Easter 1864, Levski officially relinquished his religious office.[35] From May 1864 until March 1866, he worked as a teacher in Voynyagovo near Karlovo; while there, he supported and gave shelter to persecuted Bulgarians and organised patriotic groups among the population. His activity caused suspicion among the Ottoman authorities, and he was forced to move.[24] From the spring of 1866 to the spring of 1867, he taught in Enikyoy and Kongas, two Northern Dobruja villages near Tulcea.[36][37]

Hitov's detachment and Second Bulgarian Legion

editIn November 1866, Levski visited Rakovski in Iaşi. Two revolutionary bands led by Panayot Hitov and Filip Totyu had been inciting the Bulgarian diaspora community in Romania to invade Bulgaria and organise anti-Ottoman resistance. On the recommendation of Rakovski, Vasil Levski was selected as the standard-bearer of Hitov's detachment.[22][34][38] In April 1867, the band crossed the Danube at Tutrakan, moved through the Ludogorie region and reached the Balkan Mountains.[39] After skirmishing, the band fled to Serbia through Pirot in August.[38][40][41]

In Serbia, the government was again favourable towards the Bulgarian revolutionaries' aspirations and allowed them to establish in Belgrade the Second Bulgarian Legion, an organisation similar to its predecessor and its goals. Levski was a prominent member of the Legion, but between February and April 1868 he suffered from a gastric condition that required surgery. Bedridden, he could not participate in the Legion's training.[42] After the Legion was again disbanded under political pressure, Levski attempted to reunite with his compatriots, but was arrested in Zaječar and briefly imprisoned.[5][34][43] Upon his release he went to Romania, where Hadzhi Dimitar and Stefan Karadzha were mobilising revolutionary detachments. For various reasons, including his stomach problems and strategic differences, Levski did not participate.[44] In the winter of 1868, he became acquainted with poet and revolutionary Hristo Botev and lived with him in an abandoned windmill near Bucharest.[45][46][47]

Bulgarian tours and work in Romania

editRejecting the emigrant detachment strategy for internal propaganda, Levski undertook his first tour of the Bulgarian lands to engage all layers of Bulgarian society for a successful revolution. On 11 December 1868, he travelled by steamship from Turnu Măgurele to Istanbul, the starting point of a trek that lasted until 24 February 1869, when Levski returned to Romania. During this canvassing and reconnaissance mission, Levski is thought to have visited Plovdiv, Perushtitsa, Karlovo, Sopot, Kazanlak, Sliven, Tarnovo, Lovech, Pleven and Nikopol, establishing links with local patriots.[34][48]

After a two-month stay in Bucharest, Vasil Levski returned to Bulgaria for a second tour, lasting from 1 May to 26 August 1869. On this tour he carried proclamations printed in Romania by the political figure Ivan Kasabov. They legitimised Levski as the representative of a Bulgarian provisional government. Vasil Levski travelled to Nikopol, Pleven, Karlovo, Plovdiv, Pazardzhik, Perushtitsa, Stara Zagora, Chirpan, Sliven, Lovech, Tarnovo, Gabrovo, Sevlievo and Tryavna. According to some researchers, Levski established the earliest of his secret committees during this tour,[24][47] but those assumptions are based on uncertain data.[34]

From late August 1869 to May the following year, Levski was active in the Romanian capital Bucharest. He was in contact with revolutionary writer and journalist Lyuben Karavelov, whose participation in the foundation of the Bulgarian Literary Society Levski approved in writing. Karavelov's publications gathered a number of followers and initiated the foundation of the Bulgarian Revolutionary Central Committee (BRCC), a centralised revolutionary diasporic organisation that included Levski as a founding member[21][5] and statute drafter.[49] In disagreement over planning,[21] Levski departed from Bucharest in the spring of 1870 and began to put into action his concept of an internal revolutionary network.[34]

Creation of the Internal Revolutionary Organisation

editDespite insufficient documentation of Levski's activities in 1870, it is known that he spent a year and a half establishing a wide network of secret committees in Bulgarian cities and villages. The network, the Internal Revolutionary Organisation (IRO), was centred around the Lovech Central Committee,[50] also called "BRCC in Bulgaria" or the "provisional government".[21][24] The goal of the committees was to prepare for a coordinated uprising.[51] The network of committees was at its densest in the central Bulgarian regions, particularly around Sofia, Plovdiv and Stara Zagora. Revolutionary committees were also established in some parts of Macedonia, Dobruja and Strandzha and around the more peripheral urban centres Kyustendil, Vratsa and Vidin.[50] IRO committees purchased armaments and organised detachments of volunteers.[52] According to one study, the organisation had just over 1,000 members in the early 1870s. Most members were intellectuals and traders, though all layers of Bulgarian society were represented.[21]

Individuals obtained IRO membership in secrecy: the initiation ritual involved a formal oath of allegiance over the Gospel or a Christian cross, a gun and a knife; treason was punishable by death, and secret police monitored each member's activities.[5][53] Through clandestine channels of reliable people, relations were maintained with the revolutionary diasporic community.[5][34] The internal correspondence employed encryption, conventional signs, and fake personal and committee names.[5] Although Levski himself headed the organisation, he shared administrative responsibilities with assistants such as monk-turned-revolutionary Matey Preobrazhenski, the adventurous Dimitar Obshti, and the young Angel Kanchev.[24][54]

Apocryphal and semi-legendary anecdotal stories surround the creation of Levski's Internal Revolutionary Organisation. Persecuted by the Ottoman authorities who offered 500 Turkish liras for his death and 1000 for his capture, Levski resorted to disguises to evade arrest during his travels.[55] For example, he is known to have dyed his hair and to have worn a variety of national costumes.[56] In the autumn of 1871, Levski and Angel Kanchev published the Instruction of the Workers for the Liberation of the Bulgarian People,[24] a BRCC draft statute containing ideological, organisational and penal sections. It was sent out to the local committees and to the diasporic community for discussion. The political and organisational experience that Levski amassed is evident in his correspondence dating from 1871 to 1872; at the time, his views on the revolution had clearly matured.[34]

As IRO expanded, it coordinated its activities more with the Bucharest-based BRCC. On Levski's initiative,[24] a general assembly was called between 29 April and 4 May 1872. At the assembly, the delegates approved a programme and a statute, elected Lyuben Karavelov as the organisation's leader and authorised Levski as the BRCC executive body's only legitimate representative in the Bulgarian lands.[57] After attending the assembly, Levski returned to Bulgaria and reorganised IRO's internal structure[24] in accordance with BRCC's recommendations. Thus, the Lovech Central Committee was reduced to a regular local committee, and the first region-wide revolutionary centres were founded. The lack of funds, however, precipitated the organisation into a crisis, and Levski's solitary judgements on important strategic and tactical matters were increasingly questioned.[34]

Capture and execution

editIn that situation, Levski's assistant Dimitar Obshti robbed an Ottoman postal convoy in the Arabakonak pass on 22 September 1872,[21] without approval from Levski or the leadership of the movement.[43][58] While the robbery was successful and provided IRO with 125,000 groschen, Obshti and the other perpetrators were soon arrested.[5] The preliminary investigation and trial revealed the revolutionary organisation's size and its close relations with BRCC. Obshti and other prisoners made a full confession and revealed Levski's leading role.[21][34][58][59]

Realising that he was in danger, Levski decided to flee to Romania, where he would meet Karavelov and discuss these events. First, however, he had to collect important documentation from the committee archive in Lovech, which would constitute important evidence if seized by the Ottomans.[21][24] He stayed at the nearby village inn in Kakrina, where he was surprised and arrested on the morning of 27 December 1872. Starting with the writings of Lyuben Karavelov, it was widely accepted that a priest named Krastyo Nikiforov betrayed Levski to the police. This theory has been disputed by the researchers like Ivan Panchovski and Vasil Boyanov for lack of evidence.[60]

Initially taken to Tarnovo for interrogation, Levski was sent to Sofia on 4 January. There, he was taken to trial. While he acknowledged his identity, he did not reveal his accomplices or details related to his organisation, taking full blame.[61] Ottoman authorities sentenced Levski to death by hanging. The sentence was carried out on 18 February 1873 in Sofia,[62] where the Monument to Vasil Levski now stands.[63][64] The location of Levski's grave is uncertain, but in the 1980s, writer Nikolay Haytov campaigned for the Church of St. Petka of the Saddlers as Levski's burial place, which the Bulgarian Academy of Sciences concluded as possible yet unverifiable.[65][66]

Levski's death intensified the crisis in the Bulgarian revolutionary movement,[67] and most IRO committees soon disintegrated.[68] Nevertheless, five years after Levski's hanging, the Russo-Turkish War of 1877–1878 secured the liberation of Bulgaria from Ottoman rule in the wake of the April Uprising of 1876. The Treaty of San Stefano of 3 March 1878 established the Bulgarian state as an autonomous Principality of Bulgaria under de jure Ottoman suzerainty.[69]

Revolutionary theory and ideas

editAt the end of the 1860s, Levski developed a revolutionary theory that saw the Bulgarian liberation movement as an armed uprising of all Bulgarians in the Ottoman Empire. The insurrection was to be prepared, controlled and coordinated internally by a central revolutionary organisation, which was to include local revolutionary committees in all parts of Bulgaria and operate independently from any foreign factors.[24][52] Levski's theory resulted from the repeated failures to implement Rakovski's ideas effectively, such as the use of foreign-based armed detachments (чети, cheti) to provoke a general revolt.[14][34][70] Levski's idea of an entirely independent revolution did not enjoy the approval of the entire population however—in fact, he was the only prominent Bulgarian revolutionary to advocate it. Instead, many regarded an intervention by the great powers as a more feasible solution.[68]

Levski envisioned Bulgaria as a democratic republic,[5][71] occasionally finding common ground with the Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen,[72] and largely reflecting the liberal ideas of the French Revolution and contemporary Western society.[73][74] He said, "We will be free in complete liberty where the Bulgarian lives: in Bulgaria, Thrace, Macedonia; people of whatever ethnicity live in this heaven of ours, they will be equal in rights to the Bulgarian in everything. We will have a flag that says, 'Pure and sacred republic'... It is time, by a single deed, to achieve what our French brothers have been seeking..."[4] Levski held that all religious and ethnic groups in a free Bulgaria—whether Bulgarians, Turks, Jews or others—should enjoy equal rights.[4][5][6] He reiterated that the Bulgarian revolutionaries fought against the sultan's government, not against the Turkish people[75] and their religion: "We're not driving away the Turkish people nor their faith, but the emperor and his laws (in a word, the Turkish government), which has been ruling not only us, but the Turk himself in a barbarian way."[4][71]

Levski was prepared to sacrifice his life for the revolution and place Bulgaria and the Bulgarian people above personal interests: "If I shall win, I shall win for the entire people. If I shall lose, I shall lose only myself."[22][47][76] In a liberated Bulgaria, he did not envision himself as a national leader or a high-ranking official: "We yearn to see a free fatherland, and [then] one could even order me to graze the ducks, isn't that right?"[4][71] In the spirit of Garibaldi, Levski planned to assist other oppressed peoples of the world in their liberation once Bulgaria was reestablished.[77] He also advocated "strict and regular accounting" in his revolutionary organisation, and did not tolerate corruption.[78]

Commemoration

editCry! For near the town of Sofia,

Sticks up, I saw, black gallows,

And your only son, Bulgaria,Hangs on it with fearsome strength.

Hristo Botev's "The Hanging of Vasil Levski" (1875)[52]

In cities and villages across Bulgaria, Levski's contributions to the liberation movement are commemorated with numerous monuments,[79] and many streets bear his name.[80] Monuments to Levski also exist outside Bulgaria—in Belgrade, Serbia,[81] Dimitrovgrad, Serbia,[82] Parcani, Transnistria, Moldova,[83] Bucharest, Romania,[84] Paris, France,[85] Washington, D.C., United States,[86] and Buenos Aires, Argentina.[87] Three museums dedicated to Levski have been organised: one in Karlovo,[88] one in Lovech[89] and one in Kakrina.[90] The Monument to Vasil Levski in Sofia was erected on the site of his execution.

Several institutions in Bulgaria have been named in Vasil Levski's honour; these include the football and sports club of Levski Sofia, Levski Sofia (sports club),[91] the Vasil Levski National Sports Academy[92] and the Vasil Levski National Military University.[93] Bulgaria's national stadium bears the name Vasil Levski National Stadium.[94] The 1000 Bulgarian leva banknote, in circulation between 1994 and 1999, featured Levski's portrait on its obverse side and his monument in Sofia on the reverse.[95][96] The town of Levski and six villages around the country have also been named in his honour.[97] The Antarctic Place-names Commission of Bulgaria named an Antarctic ridge and peak on Livingston Island of the South Shetland Islands Levski Ridge and Levski Peak respectively.[98][99]

The life of Vasil Levski has been widely featured in Bulgarian literature and popular culture. Poet and revolutionary Hristo Botev dedicated his last work to Levski, "The Hanging of Vasil Levski". The poem, an elegy,[100] was probably written in late 1875.[101] Prose and poetry writer Ivan Vazov devoted an ode to the revolutionary. Eponymously titled "Levski", it was published as part of the cycle Epic of the Forgotten.[102] Levski has also inspired works by writers Hristo Smirnenski[103] and Nikolay Haytov,[104] among others. Songs devoted to Levski can be found in the folklore tradition of Macedonia as well.[105] In February 2007, a nationwide poll conducted as part of the Velikite Balgari ("The Great Bulgarians") television show, a local spin-off of 100 Greatest Britons, named Vasil Levski the greatest Bulgarian of all time.[7]

There have been motions to glorify Vasil Levski as a saint of the Bulgarian Orthodox Church. However, historian Stefan Chureshki has emphasised that while Levski's post-monastical life was one of a martyr, it was incompatible with the Orthodox concept of sainthood. Chureshki makes reference to Levski's correspondences, which show that Levski threatened wealthy Bulgarians (чорбаджии, chorbadzhii) and traitors with death, endorsed theft from the rich for pragmatic revolutionary purposes and voluntarily gave up his religious office to devote himself to the secular struggle for liberation.[106]

Vasil Levski's hanging is observed annually across Bulgaria on 19 February[107] instead of 18 February, due to the erroneous calculation of 19th-century Julian calendar dates after Bulgaria adopted the Gregorian calendar in 1916.[108] Although the location of Levski's grave has not been determined, some of his hair is on exhibit at the National Museum of Military History. After Levski gave up monkhood in 1863, he shaved his hair, which his mother and later his sister Yana preserved. Levski's personal items—such as his silver Christian cross, his copper water vessel, his Gasser revolver, made in Austria-Hungary in 1869, and the shackles from his imprisonment in Sofia—are also exhibited in the military history museum,[109] while Levski's sabre can be seen in the Lovech regional museum.[89]

Vasil Levski is referenced by the video game Star Citizen, in which future society "The People's Alliance of Levski" adopt an ideology based upon his views.[110]

A pond in the Arbor Hills Nature Preserve in Plano, Texas is named in honor of Vasil Levski.[111]

References

editFootnotes

edit- ^ First name also transliterated as Vassil, alias archaically written as Levsky in English (cf. MacDermott).

- ^ Унджиев 1980, p. 53

- ^ Family name also transliterated as Kunčev, Kountchev, Kuntchev, etc.

- ^ a b c d e "Идеи за свободна България". Archived from the original on 11 April 2009. Retrieved 11 April 2009.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link), 170 години. - ^ a b c d e f g h i j Manova, Zhelev & Mitev 2007

- ^ a b Crampton 2007, p. 422

- ^ a b "Васил Левски беше избран за най-великия българин на всички времена" (in Bulgarian). Великите българи. 18 February 2007. Archived from the original on 17 March 2007. Retrieved 24 October 2008.

- ^ De Bellaigue, Christopher (5 July 2001). "The Sick Man of Europe". The New York Review of Books. Archived from the original on 30 September 2008. Retrieved 24 October 2008.

- ^ Castellan 1999, pp. 221–222

- ^ Castellan 1999, pp. 315–317

- ^ Castellan 1999, p. 258

- ^ Castellan 1999, p. 272

- ^ Roudometof 2001, p. 136

- ^ a b "Vasil Levski". Encyclopædia Britannica Online. 2008. Archived from the original on 12 March 2009. Retrieved 24 October 2008.

- ^ Кондарев 1946, p. 24

- ^ Стоянов 1943, p. 37

- ^ Кондарев 1946, p. 13

- ^ Дойчев, Л (1981). Сподвижници на Апостола (in Bulgarian). София: Отечество. OCLC 8553763.

- ^ "Vassil Levski's house". Музей "Васил Левски", гр. Карлово. Archived from the original on 24 April 2008. Retrieved 24 October 2008.

- ^ "Външен вид Archived 18 February 2010 at the Wayback Machine", 170 години.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Crampton 2007, pp. 89–90

- ^ a b c d Crampton 1997, p. 79

- ^ Кондарев 1946, pp. 27–28

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Бакалов & Куманов 2003

- ^ "Левски". Православие БГ (in Bulgarian). 20 February 2008. Archived from the original on 12 January 2009. Retrieved 25 October 2008.

- ^ Seasons in this article are to be understood as seasons in the Northern Hemisphere, i.e. spring is in the beginning of the year.

- ^ Стоянов 1943, pp. 45–48

- ^ Trankova, Dimana. "WHO WAS VASIL LEVSKI?". Vagabond. Archived from the original on 24 September 2016. 24 February 2012

- ^ Trotsky, Leon; Brian Pearce; George Weissman; Duncan Williams (1980). The War Correspondence of Leon Trotsky. The Balkan Wars, 1912-13. Resistance Books. p. 487. ISBN 0-909196-08-7.

- ^ Trotsky, Pearce, Weissman & Williams 1980, p.487.

- ^ "Автобиография". Archived from the original on 15 April 2009. Retrieved 15 April 2009.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link), 170 години. - ^ Дойнов & Джевезов 1996, p. 11

- ^ Кондарев 1946, pp. 36–39

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k "Живот и дело". Archived from the original on 13 February 2010. Retrieved 23 October 2008.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link), 170 години. - ^ Унджиев 1980, p. 60

- ^ Стоянов 1943, pp. 67–68

- ^ Унджиев 1980, pp. 63–64

- ^ a b Дойнов & Джевезов 1996, p. 12

- ^ Бакалов, Георги; Милен Куманов (2003). "ХИТОВ, Панайот Иванов (1830–22.II.1918)". Електронно издание "История на България" (in Bulgarian). София: Труд, Сирма. ISBN 954528613X.

- ^ Стоянов 1943, pp. 70–72

- ^ Кондарев 1946, p. 59

- ^ Кондарев 1946, pp. 59–61

- ^ a b Crampton 2007, p. 89

- ^ Кондарев 1946, pp. 78–79

- ^ "Христо Ботев загива на този ден през 1876 г" (in Bulgarian). Будилникъ. 2 June 2007. Archived from the original on 8 July 2011. Retrieved 24 October 2008.

- ^ "Васил Левски и Христо Ботев". Archived from the original on 27 December 2008. Retrieved 27 December 2008.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link), 170 години. - ^ a b c Дойнов & Джевезов 1996, p. 17

- ^ Кондарев 1946, pp. 86–87

- ^ Perry 1993, p. 9

- ^ a b Дойнов & Джевезов 1996, p. 19

- ^ Stavrianos 2000, p 378.

- ^ a b c Vatahov, Ivan (20 February 2003). "Vassil Levski — Bulgaria's 'only son'". The Sofia Echo. Retrieved 24 October 2008.

- ^ Стоянов 1943, pp. 83, 86

- ^ Стоянов 1943, pp. 85–86

- ^ Дойнов & Джевезов 1996, p. 20

- ^ Стоянов 1943, p. 87

- ^ Кондарев 1946, pp. 160–161

- ^ a b Jelavich & Jelavich 1986, p. 138

- ^ Диковски, Цветан (2007). "Някои спорни факти около предателството на Васил Левски" (in Bulgarian). LiterNet. Archived from the original on 29 December 2008. Retrieved 24 October 2008.

- ^ "Краят на една клевета" (in Bulgarian). Църковен вестник. Archived from the original on 7 December 2008. Retrieved 24 October 2008.

- ^ Стоянов 1943, p. 128

- ^ Todorova, Maria (2003). "Memoirs, Biography, Historiography: The Reconstruction of Levski's Life Story". Études balkaniques. 1. Sofia: Académie bulgare des sciences: 23.

- ^ Николов, Григор (8 November 2005). "За паметника на Левски дарили едва 3000 лева" (in Bulgarian). Сега. Archived from the original on 21 April 2008. Retrieved 24 October 2008.

- ^ Miller 1966, p. 346

- ^ "Гробът на Васил Левски" (in Bulgarian). Ziezi ex quo Vulgares. Archived from the original on 18 October 2008. Retrieved 24 October 2008.

- ^ Todorova 2007, p. 165

- ^ Daskalov 2004, p. 188

- ^ a b Dimitrov 2001

- ^ Castellan 1999, pp. 322–324

- ^ Jelavich & Jelavich 1986, p. 136

- ^ a b c Дойнов & Джевезов 1996, p. 21

- ^ Cornis-Pope & Neubauer 2004, p. 317

- ^ Чурешки, Стефан (17 February 2006). "Идеите на Левски и модерността" (in Bulgarian). Сега. Archived from the original on 19 July 2011. Retrieved 24 October 2008.

- ^ Hrissimova, Ognyana (1999). "Les idées de la révolution française de 1789 et les droits réels de l'homme et du citoyen dans les Constitutions de Etats nationaux des Balkans". Études balkaniques (in French). 3–4. Sofia: Académie bulgare des sciences: 17. ISSN 0324-1645.

- ^ Daskalov 2004, p. 61

- ^ "Ако спечеля, печеля за цял народ — ако загубя, губя само мене си" (in Bulgarian). Свята и чиста република. Archived from the original on 25 September 2008. Retrieved 24 October 2008.

- ^ Кьосев, Александър (24 February 2007). "Величие и мизерия в епохата на Водолея" (in Bulgarian). Сега. Archived from the original on 19 July 2011. Retrieved 25 October 2008.

- ^ Тодоров, Петко. "Близо ли е времето?" (PDF) (in Bulgarian). Земя. Archived from the original (PDF) on 30 October 2008. Retrieved 24 October 2008.

- ^ "Списък на войнишките паметници и паметниците, свързани с борбите за национално освобождение" (PDF) (in Bulgarian). Национално движение "Българско наследство". Archived (PDF) from the original on 30 October 2008. Retrieved 24 October 2008.

- ^ Петров, Пламен (11 October 2007). "Мистерията на варненските улици" (in Bulgarian). DARIK Radio. Archived from the original on 15 January 2008. Retrieved 24 October 2008.

- ^ "Откриват паметник с ликовете на Левски и Раковски в Белград" (in Bulgarian). Actualno.com. 18 December 2007. Archived from the original on 2 November 2008. Retrieved 24 October 2008.

- ^ "Орешарски и Дачич откриха бюст на Левски в Цариброд" (in Bulgarian). Btvnews.bg. 18 February 2014. Archived from the original on 19 February 2014. Retrieved 19 February 2014.

- ^ "Откриха паметник на Левски в Приднестровието" (in Bulgarian). Блиц. 23 September 2008. Archived from the original on 23 July 2011. Retrieved 24 October 2008.

- ^ "Министър Славински откри паметник на Левски в Букурещ" (in Bulgarian). Министерство на транспорта. 12 May 2001. Retrieved 24 October 2008.

- ^ "Първанов откри барелеф на Васил Левски в Париж" (in Bulgarian). News.bg. 16 October 2007. Archived from the original on 6 October 2008. Retrieved 24 October 2008.

- ^ "Васил Левски — символ на националното ни достойнство" (in Bulgarian). Kazanlak.com. 19 February 2004. Retrieved 24 October 2008.

- ^ "Българската общност в Аржентина почете паметта на Васил Левски" (in Bulgarian). Посолство на Република България, Буенос Айрес, Аржентина. 18 February 2007. Retrieved 26 April 2009. [dead link]

- ^ "Vassil Levski Museum — Karlovo". Vassil Levski Museum — Karlovo. Archived from the original on 24 September 2008. Retrieved 24 October 2008.

- ^ a b "Музей "Васил Левски"" (in Bulgarian). Исторически музей Ловеч. Archived from the original on 8 December 2008. Retrieved 24 October 2008.

- ^ "Музей Къкринско ханче" (in Bulgarian). Archived from the original on 7 January 2009. Retrieved 24 October 2008.

- ^ "History: Patron". PFC Levski Sofia. Archived from the original on 11 December 2008. Retrieved 24 October 2008.

- ^ "National Sports Academy (NSA) "Vassil Levski"". National Sports Academy (NSA) "Vassil Levski". Archived from the original on 17 September 2008. Retrieved 24 October 2008.

- ^ "Добре дошли в сайта на НВУ "В. Левски"" (in Bulgarian). Archived from the original on 24 October 2008. Retrieved 24 October 2008.

- ^ "Vassil Levski National Stadium". National Sport Base. Archived from the original on 13 September 2008. Retrieved 24 October 2008.

- ^ Natseva, Rosalina; Lyuben Ivanov; Ines Lazarova; Petya Krusteva (2004). Catalogue of Bulgarian Banknotes (PDF). Sofia: Bulgarian National Bank. p. 109. ISBN 954-9791-74-2. Archived (PDF) from the original on 31 October 2008.

- ^ "Bulgarian Banknotes". Ivan Petrov. Archived from the original on 27 February 2009. Retrieved 20 January 2009.

- ^ "Таблица на населението по постоянен и настоящ адрес" (in Bulgarian). Главна дирекция "Гражданска регистрация и административно обслужване". 16 June 2008. Archived from the original on 20 October 2008. Retrieved 24 October 2008.

- ^ "Composite Antarctic Marine Gazetteer Placedetails: Levski Ridge". SCAR-MarBIN Portal. Archived from the original on 7 March 2017. Retrieved 24 October 2008.

- ^ "Composite Antarctic Marine Gazetteer Placedetails: Levski Peak". SCAR-MarBIN Portal. Archived from the original on 7 March 2017. Retrieved 24 October 2008.

- ^ ""Обесването на Васил Левски" – Христо Ботев" (in Bulgarian). Изкуството.com. 23 May 2008. Archived from the original on 29 January 2010. Retrieved 24 October 2008.

- ^ Ботев, Христо. "Обесването на Васил Левски". Slovo.bg. Archived from the original on 16 May 2007. Retrieved 24 October 2008.

- ^ Вазов, Иван. "Епопея на забравените: Левски" (in Bulgarian). Slovo.bg. Retrieved 24 October 2008.

- ^ Смирненски, Христо. "Левски" (in Bulgarian). Slovo.bg. Archived from the original on 16 October 2007. Retrieved 24 October 2008.

- ^ "Николай Хайтов" (in Bulgarian). Archived from the original on 12 September 2008. Retrieved 24 October 2008.

- ^ Църнушанов, Коста (1989). ""Песна за Васил Левски" от Тиквешията". Български народни песни от Македония (in Bulgarian). София: Държавно издателство "Музика". p. 395. OCLC 248012186.

- ^ Чурешки, Стефан (29 August 2005). "Левски в измеренията на светостта" (in Bulgarian). Православие БГ. Retrieved 24 October 2008.[permanent dead link]

- ^ "Bulgaria Commemorates the Apostle of Freedom". Sofia News Agency. 19 February 2008. Archived from the original on 24 February 2012. Retrieved 25 October 2008.

- ^ Павлов, Петко (19 February 2007). "Левски е обесен на 18, а не на 19 февруари" (in Bulgarian). DARIK Radio. Archived from the original on 6 July 2011. Retrieved 25 October 2008.

- ^ Жеков, Венцислав; Йорданка Тотева (2007). "Личните вещи на Левски се съхраняват при специални климатични условия" (in Bulgarian). Българска армия. Retrieved 25 October 2008.

- ^ "Galactic Guide: Nyx System - Roberts Space Industries | Follow the development of Star Citizen and Squadron 42".

- ^ "Google Maps".

Bibliography

edit- Castellan, Georges (1999). Histoire des Balkans, XIVe–XXe siècle (in French). transl. Lilyana Tsaneva (Bulgarian translation ed.). Paris: Fayard. ISBN 2-213-60526-2.

- Cornis-Pope, Marcel; Neubauer, John (2004). History of the literary cultures of East-Central Europe: junctures and disjunctures in the 19th and 20th centuries. John Benjamins Publishing Company. ISBN 90-272-3452-3..

- Crampton, R.J. (2007). Bulgaria. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-820514-2.

- Crampton, R.J. (1997). A Concise History of Bulgaria. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-56183-3.

- Daskalov, Rumen (2004). The Making of a Nation in the Balkans: Historiography of the Bulgarian Revival. Central European University Press. ISBN 963-9241-83-0.

- Dimitrov, Vesselin (2001). Bulgaria: The Uneven Transition. Routledge. ISBN 0-415-26729-3.

- Jelavich, Charles; Jelavich, Barbara (1986). The Establishment of the Balkan National States, 1804–1920: A History of East Central Europe. University of Washington Press. ISBN 0-295-96413-8.

- MacDermott, Mercia (1962). A History of Bulgaria 1395–1885. New York: Frederick A. Praeger – via Internet Archive.

- MacDermott, Mercia (1967). The Apostle of Freedom: A Portrait of Vasil Levsky Against a Background of Nineteenth Century Bulgaria. London: G. Allen and Unwin. OCLC 957800.

- Manova, Denitza; Zhelev, Radostin; Mitev, Plamen (19 February 2007). "The Apostle of Freedom — organizer and ideologist of the national liberation struggle". BNR Radio Bulgaria. Archived from the original on 17 March 2008. Retrieved 25 October 2008.

- Miller, William (1966). The Ottoman Empire and Its Successors, 1801–1927. Routledge. ISBN 0-7146-1974-4.

- Perry, Duncan M. (1993). Stefan Stambolov and the Emergence of Modern Bulgaria, 1870–1895. Duke University Press. ISBN 0-8223-1313-8.

- Roudometof, Victor (2001). Nationalism, Globalization, and Orthodoxy: The Social Origins of Ethnic Conflict in the Balkans. Greenwood Publishing Group. ISBN 0-313-31949-9.

- Stavrianos, Leften Stavros (2000). The Balkans Since 1453. C. Hurst & Co. Publishers. ISBN 1-85065-551-0.

- Ternes, Elmar; Tatjana Vladimirova-Buhtz (1999). "Bulgarian". Handbook of the International Phonetic Association: A Guide to the Use of the International Phonetic Alphabet. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 55–57. ISBN 0-521-63751-1.

- Todorova, Maria (2007). "Was there civil society and a public sphere under socialism? The debates around Vasil Levski's alleged burial in Bulgaria". Schnittstellen: Gesellschaft, Nation, Konflikt und Erinnerung in Südosteuropa : Festschrift für Holm Sundhaussen zum 65. Geburtstag. Oldenbourg Wissenschaftsverlag. ISBN 978-3-486-58346-5.

- Trotsky, Leon; Brian Pearce; George Weissman; Duncan Williams (1980). The War Correspondence of Leon Trotsky. The Balkan Wars, 1912–13. Resistance Books. ISBN 0-909196-08-7.

- Бакалов, Георги; Куманов, Милен (2003). "ЛЕВСКИ, Васил (В. Иванов Кунчев, Дякона, Апостола) (6/19.VII.1837-6/18.II.1873)". Електронно издание "История на България" (in Bulgarian). София: Труд, Сирма. ISBN 954528613X.

- Дойнов, Дойно; Джевезов, Стоян (1996). "Не щях да съм турски и никакъв роб". Къща-музей Васил Левски Карлово (in Bulgarian). София: Славина. OCLC 181114302.

- Кондарев, Никола (1946). Васил Левски. Биография (in Bulgarian). София: Издателство на Бълг. Работническа Партия (Комунисти). OCLC 39379012. Archived from the original on 26 August 2021. Retrieved 23 October 2008.

- Рачева, Ваня Николова (2007). "170 години от рождението на Васил Левски" (in Bulgarian). Държавна агенция за българите в чужбина. Archived from the original on 15 June 2008. Retrieved 23 October 2008.

- Симеонова, Маргарита Василева (2007). Езиковата личност на Васил Левски (in Bulgarian). София: Академично издателство "Марин Дринов". ISBN 978-954-322-196-7. OCLC 237020336.

- Стоянов, Захарий (1943) [1883]. Василъ Левски (Дяконътъ). Черти изъ живота му (in Bulgarian). Пловдив, София: Новъ Свѣтъ. OCLC 4273683. Archived from the original on 25 February 2021. Retrieved 23 October 2008.

- Страшимиров, Димитър (1995). Левски пред Къкринската голгота: история и критика (in Bulgarian). София: Сибия. ISBN 954-8028-29-8. OCLC 33205249.

- Унджиев, Иван (1980). Васил Левски. Биография (in Bulgarian) (Второ издание ed.). София: Наука и изкуство. OCLC 251739767.

External links

edit- Pure and Sacred Republic — Levski's letters and documents (in Bulgarian)

- Online edition of Vasil Levski's personal notebook (in Bulgarian)

- Vasil Levski in Haskovo (in English)

- Vasil Levski Museum in Karlovo (in English and Bulgarian)

- Vasil Levski Foundation (in Bulgarian)