Coeur d'Alene (/ˌkɔːr dəˈleɪn/ KOR də-LAYN;[6][7][8] French: Cœur d'Alène, lit. 'Heart of Awl' French pronunciation: [kœʁ d a.lɛn]) is a city and the county seat of Kootenai County, Idaho, United States. It is the most populous city in North Idaho and the principal city of the Coeur d'Alene Metropolitan Statistical Area. The population was 54,628 at the 2020 census.[4] Coeur d'Alene is a satellite city of Spokane, which is located about thirty miles (50 km) to the west in the state of Washington. The two cities are the key components of the Spokane–Coeur d'Alene Combined Statistical Area, of which Coeur d'Alene is the third-largest city (after Spokane and its largest suburb, Spokane Valley). The city is situated on the north shore of the 25-mile (40 km) long Lake Coeur d'Alene and to the west of the Coeur d'Alene Mountains. Locally, Coeur d'Alene is known as the "Lake City", or simply called by its initials, "CDA".

Coeur d'Alene | |

|---|---|

Aerial view of Coeur d'Alene Coeur d'Alene Resort and marina Floating boardwalk Independence Point Coeur d'Alene Resort floating green Coeur d'Alene and Tubbs Hill from City Park and Beach | |

| Nickname(s): Lake City; CDA | |

| Motto: City with a Heart[1] | |

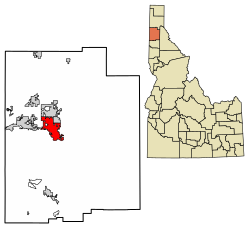

Location of Coeur d'Alene in Kootenai County, Idaho | |

| Coordinates: 47°41′34″N 116°46′48″W / 47.69278°N 116.78000°W | |

| Country | United States |

| State | Idaho |

| County | Kootenai |

| Founded | 1878 |

| Incorporated (town) | August 22, 1887 |

| Incorporated (city) | September 4, 1906 |

| Government | |

| • Mayor | Woody McEvers |

| Area | |

• City | 16.82 sq mi (43.56 km2) |

| • Land | 16.06 sq mi (41.58 km2) |

| • Water | 0.76 sq mi (1.98 km2) |

| Elevation | 2,188 ft (667 m) |

| Population | |

• City | 54,628 |

• Estimate (2022)[5] | 56,733 |

| • Rank | US: 702nd ID: 7th |

| • Density | 3,522.0/sq mi (1,360.0/km2) |

| • Urban | 121,831 (US: 272nd) |

| • Metro | 183,578 (US: 240th) |

| • Combined | 781,497 (US: 70th) |

| Time zone | UTC–8 (Pacific (PST)) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC–7 (PDT) |

| ZIP Codes | 83814, 83815 |

| Area code(s) | 208 and 986 |

| FIPS code | 16-16750 |

| GNIS feature ID | 0379485[3] |

| Website | cdaid.org |

The city is named after the Coeur d'Alene people, a federally recognized tribe of Native Americans who live along the rivers and lakes of the region, in a territory of 4,000,000 acres (16,000 km2) from eastern Washington to Montana. The native peoples were hunter-gatherers who located their villages and camps near food gathering or processing sites and followed the seasonal cycles, practicing subsistence hunting, fishing, and foraging.

The city began as a fort town; General William Tecumseh Sherman sited what became known as Fort Sherman on the north shore of Lake Coeur d'Alene in 1878. Peopling of the town came when miners and prospectors came to the region after gold and silver deposits were found in what would become the Silver Valley and after the Northern Pacific Railroad reached the town in 1883. In the 1890s, two significant miners' uprisings over wages took place in the Coeur d'Alene Mining District leading to the declaration of martial law, with the latter providing a motive for the assassination of a former Idaho governor and subsequently a nationally publicized trial. The late 19th century discovery of highly prized white pine in the forests of northern Idaho resulted in a timber boom that peaked in the late 1920s and was accompanied by the rapid population growth which led to the incorporation of the city on September 4, 1906. After the Great Depression, tourism started to become a major source of development in the area. By the 1980s, tourism became the major driver in the local economy, and, after decades of heavy reliance on logging, the city featured a more balanced economy with manufacturing, retail, and service sectors.

The city of Coeur d'Alene has grown significantly since the 1990s, in part because of a substantial increase in tourism, encouraged by resorts and recreational activities in the area and outmigration predominantly from other western states. The Coeur d'Alene Resort and its 0.75-mile (1.21 km) floating boardwalk and a 165-acre (0.67 km2) natural area called Tubbs Hill take up a prominent portion of the city's downtown. Popular parks such as City Park and Beach and McEuen Park are also fixtures of the downtown waterfront. The city has become somewhat of a destination for golfers; there are five courses in the city, including the Coeur d'Alene Resort Golf Course and its unique 14th hole floating green. The Coeur d'Alene Casino and its Circling Raven Golf Club is located approximately 27 miles (43 km) south and the largest theme park in the Northwestern United States, Silverwood Theme Park, is located approximately twenty miles (30 km) north. There are also several ski resorts and other recreation areas nearby. The city is home to the Museum of North Idaho and North Idaho College, and it has become known for having one of the largest holiday light shows in the United States and hosting a popular Ironman Triathlon event. Coeur d'Alene is located on the route of Interstate 90 and is served by the Coeur d'Alene Airport as well as the Brooks Seaplane Base by air. In print media, local issues are covered by the Coeur d'Alene Press daily newspaper.

History

editThe Coeur d'Alene people called themselves Schitsu'umsh in Coeur d'Alene, one of the Salishan languages, meaning "those who are found here"[9][10] or "the found ones".[11] These Native Americans lived along the rivers and lakes of the region, in a territory of 4,000,000 acres (16,000 km2) extending from eastern Washington to Montana; these tribes primarily located their villages and camps near food gathering or processing sites.[9][10] The camps featured conical lodges constructed from poles and mats sewn from tule or animal hides.[9] The Coeur d'Alene people were hunter-gatherers who practiced subsistence hunting of wild game and fishing during the salmon runs, and then foraging for berries and other edibles along the shores of the region's numerous lakes and rivers.[9][10] The introduction of the horse c. 1760 made hunting and transportation more efficient.[9][10]

1800s

editThe area was extensively explored by fur trader David Thompson of the North West Company starting in 1807 and in 1809 he established the Kullyspell House trading post on Lake Pend Oreille.[11][a] Thompson, who usually used native names to describe the places and people he came across, ascribed the name of 'Pointed Hearts' to one of the tribes he traded with and "Pointed Heart Lake" for the lake they lived near.[11] Since Thompson traveled with French-speaking Iroquois guides and scouts, it has been speculated that they may have been the first to refer to the tribe as the Coeur d'Alene.[9][10] As French was the spoken language of the Canadian fur traders, it is likely that "pointed heart" has its origins in the French transliteration of Cœur or "heart", d' or "in the middle of" and Alêne or "awl", meaning the tribal traders had hearts as sharp as the tip of an awl – or that they were sharp businessmen.[11][10]

The Oregon boundary dispute (or Oregon question) arose as a result of competing British and American claims to the Pacific Northwest of North America in the first half of the 19th century. The British had trading ties extending from Canada and had started settlements at Fort Vancouver and at Fort Astoria on the Pacific coast near the mouth of the Columbia River. The Oregon Treaty of 1846 ended the disputed joint occupation of the area in present-day Idaho when Britain ceded all rights to land south of the 49th parallel to the United States.[12]

In another territorial dispute, the U.S. government through Washington Territory Governor Isaac Stevens began to negotiate treaties that would begin to move the various tribes of the region onto reservation lands to make way for American settlement.[13] This angered the Coeur d'Alene, as several treaty re-negotiations continually reduced their tribal lands.[13] The tribe also perceived the planned construction a military wagon road as a precursor to a land-grab by the United States.[14] These talks and increasing settler encroachment sparked armed hostilities between the native Coeur d'Alene, Spokane and Palouse and the settler populations that resulted in an initial victory for the tribes at the Battle of Steptoe Butte but were followed up with George Wright's campaign that subdued the natives.[13] The Coeur d'Alene Reservation is located in Benewah and Kootenai counties south of Coeur d'Alene in communities focused around Worley and Plummer.[15] In 1859, with U.S. funding in place, Governor Stevens appointed John Mullan to survey the interior of the Northwestern United States for possible railroad routes and oversee the construction of the 611-mile (983 km) Mullan Road that bears his name, from Fort Walla Walla on the Columbia River through the Rocky Mountains to Fort Benton on the Missouri River.[16]

With the discovery of gold in the western United States and the establishment of Idaho Territory in 1863, there was an increase in settlers to the region.[17] When General William Tecumseh Sherman was commander of the U.S. Army during the Indian Wars and following the defeat of General George Armstrong Custer at the Battle of Little Big Horn, he erected several forts in the west.[17] During a tour of the Inland Northwest on his way to Fort Walla Walla on the Mullan Road, he was impressed by the scenery of the area and ordered a fort constructed on the lake in 1877 and gave it the name Fort Coeur d'Alene.[17] The fort which gave the city its name was established in 1878 and the name of the fort was later changed to Fort Sherman to honor the general.[17]

Miners and prospectors came to the region after gold and silver deposits were found in the Coeur d'Alene Mountains and the Northern Pacific Railroad came to the village in 1883.[18] The village became the location where ore from the mining district was ferried and transferred to the rail lines from steamboats that traveled down from the Coeur d'Alene River from the Cataldo Mission.[19] The township was officially incorporated by petition on August 22, 1887.[20]

In the 1890s, two significant miners' uprisings took place in the Coeur d'Alene Mining District, where the workers struggled with high risk and low pay. In 1892, the union's discovery of a labor spy in their midst, in the person of Charlie Siringo, a sometime cowboy and Pinkerton agent, resulted in a labor strike that developed into a shooting war between miners and the company in Burke Canyon. When the mine owners planned to reduce wages of some workers to offset increased operating costs, the miners declared a strike against the reduction of wages and the increase in work hours and demanded a "living wage"[21] be paid to every man working underground – the common laborer as well as the skilled in a stand for industrial unionism.[22] To restore order to the state of rebellion in Shoshone County, Governor N. B. Willey declared martial law and sent federal troops to arrest and detain the union miners, but not before dozens of casualties including six deaths and the destruction of the Frisco Mill.[22] Six hundred miners were put into "bullpens" without any hearings or formal charges.[23]

Labor disputes between some company mines and the union continued into the next decade. A similar labor confrontation in 1899 took place after the union was launching an organizing drive of the few mines not yet fully unionized,[24] where miners working in the Bunker Hill and Sullivan mines were receiving fifty cents to a dollar less per day than other miners.[25] With no success in the effort, on April 29, 250 union members seized a train in Burke at gunpoint, according to the engineer, Levi "Al" Hutton.[26] At each stop through Burke Canyon, more miners climbed aboard what was dubbed the "Dynamite Express" toward the site of the $250,000 Bunker Hill mine near Wardner; the miners then carried 3,000 pounds (1,400 kg) of dynamite into the mill and completely destroyed it.[27] The crowd also burned down the company office, the boarding house, and the home of the mine manager. Like in the 1892 strike, martial law was declared by Governor Frank Steunenberg and wholesale arrests and mass incarcerations were done to bring back order.[22] Harry Orchard, who owned a share of the Hercules Mine at one point and played a significant role in the Colorado Labor Wars, returned to Idaho to assassinate former governor Steunenberg in 1905.[28] The bombing assassination led to a nationally publicized trial in Boise.[22]

After a U.S. Geological Survey done in the 1890s, it became widely known that there were large quantities of white pine, a highly prized softwood, in the Coeur d'Alene Mountains.[29] The lumber industry from the eastern US began to inventory the timberlands, acquire land, and invest in facilities across much of northern Idaho.[29] This was welcome relief to the town of Coeur d'Alene, which had been reeling from the Panic of 1893, a flood in 1894, and the closure of Fort Sherman.[29][b]

1900s

editThe city experienced significant growth from the timber boom and the development of the railroads, steamboats, and tourism that accompanied it; Coeur d'Alene incorporated as a city on September 4, 1906, and by 1908 it had become the county seat.[31] From 1900 to 1915, there were hundreds of homes constructed across 70 newly platted additions.[32] With the advent of the automobile and the internal combustion engine, trucks and chainsaws, the felling and transporting of trees became more productive and efficient and lumber production reached its height in the late 1910s and 1920s; in 1925 there were seven lumber mills operating in the area and they were producing 500 million board feet of lumber.[33]

After the 1929 stock market crash and during the Great Depression, the lumber industry demand began to wane and by the mid-1930s about half the woodworkers in North Idaho were laid off and the surviving mills were producing only 160 million board feet of lumber per year.[34] Although it was a tough time, accomplishments during the Depression years included the establishment of Coeur d'Alene Junior College (North Idaho College) in 1933, the construction of Northwest Boulevard through the Works Progress Administration program in 1937, and the building of the popular Playfair Pier amusement park on the lake in the early 1940s.[35] The Playfair Pier opened on July 4, 1942 (and existed until 1974) in City Park and included a variety of rides and attractions such as a miniature roller coaster, a Ferris wheel, a carousel, and some of the usual carnival games.[36] Coeur d'Alene benefited from its proximity to the Farragut Naval Training Station, established in 1942 on the south end of Lake Pend Oreille, which employed 22,000 people and needed 98 million board feet of lumber to build 650 buildings.[37]

Due to the scenic lake, tourism has always been a factor in the local economy. In the early 1900s, it had become popular in Spokane to travel and picnic in the park, shop in town, and take steamboat cruises on the lake and up the Saint Joe River.[29] Coeur d'Alene had also received national publicity in magazines, where it had been called a "wonderland" and "the Lucerne of America".[38] However, tourism began to become a mainstay of the economy with the completion of highway infrastructure projects in the 1950s and 1960s, and the Coeur d'Alene Chamber of Commerce began to promote the city as a tourist destination as well.[39] As tourism increased, there was more demand for lodging facilities, convention space, restaurants, and cultural activities. By 1976, the city had over 30 motels with about 1,500 rooms.[40] On June 14, 1958, the city hosted the first Diamond Cup Hydroplane race, which was one of the largest events in its history and garnered national publicity and media coverage.[41] The event was attended by 30,000 people, and it was considered a success by the Diamond Cup organizers. The race was held at Lake Coeur d'Alene for the next eight years; it was discontinued due to persistent difficulties in raising funds for the event.[41]

After decades of heavy reliance on logging, in the 1980s, the city featured a more balanced economy with manufacturing, retail, and service sectors.[42] Tourism has taken on even more prominence and has become one of the main drivers of the local economy since the start of the 1980s, when there was new investment into recreational tourism in the area. In 1982, a $2 million Wild Waters aquatic theme park was built, and in the spring of 1986 there was the opening of the $60 million ($167 million in 2023 dollars), 18-story Coeur d'alene Resort.[43] The waterfront resort featured a well-manicured frontage and a publicly accessible floating boardwalk that gave visitors the impression of a park-like environment and attracted the attention of publications nationwide.[43][44] The actions of the Aryan Nations, a white supremacist group founded by Richard Butler in 1974, also attracted media attention.[45] Butler's acolytes, many of whom were transplants like him, were linked to several robberies, murders, and three bombings, including the bombing of a Spokesman-Review office.[46][45] In 1986, Coeur d'Alene was presented the Raoul Wallenberg Award for its stand in peacefully countering the message of the white supremacists that moved into the area.[47][45] Coeur d'Alene also won the All-America City Award in 1990.[48] The Aryan Nations went bankrupt and ceased operations in 2000 when the Southern Poverty Law Center filed a lawsuit after the assault of a Native American woman. The lawsuit resulted in a $6.3 million judgment and the closure of their Hayden compound.[45]

In the 1990s, the Coeur d'Alene area starting experiencing substantial population growth; many of these initial transplants came from California, citing earthquakes, crime, and overcrowding as reasons for their move.[46] This northward migration coincided with watershed events such as the 1992 Los Angeles riots and the 1994 Northridge earthquake.[49] The surrounding area got increased tourist attention when Silverwood Theme Park, which opened in 1988 on an airstrip with an authentic steam train and carnival rides, installed the Corkscrew roller coaster in 1990 that it purchased from Knott's Berry Farm.[50][51] Additional rides such as the Timber Terror and Tremors roller coasters in the 1990s and the 20-acre (0.081 km2) Boulder Beach water park in 2003 made Silverwood into a regional theme park, which attracts visitors primarily from the Spokane, Tri-Cities, and Seattle areas of Washington as well as some from the Canadian provinces of British Columbia and Alberta.[50] I

2000s

editIn 2014, McEuen Park on the downtown waterfront reopened to the public after undergoing a major $20 million renovation that transformed it from a park with baseball diamonds into a multi-use park with a variety of athletic facilities, a playground, and a dog park.[52] The state of Idaho is the fastest-growing state in the country and according to Census Bureau data in 2018, the city and county were among the fastest growing metropolitan areas in the nation with a net migration of about 3,200 residents from 2015 to 2016.[53] The newest transplants are still mainly from other western states and are moving for economic as well as political reasons, seeking a lower cost of living, more affordable housing, an outdoor lifestyle, and a place that is more conservative.[53]

In March 2024, Coeur d'Alene was at the center of a racial incident. During the 2024 NCAA Women's Basketball tournament, local residents hurled racial insults at players of the University of Utah Women's Basketball team on multiple occasions.[54]

Recent Political and Social Developments

editCoeur d'Alene has experienced notable changes in its political and social dynamics in recent years, driven in part by an influx of residents aligned with the Make America Great Again movement. Supporters argue this reflects a revival of conservative values in the region, while others express concerns about the influence of far-right ideologies. These tensions have played out across various aspects of community life, including education, gun culture, and local events.

Gun Culture and Notable Events

editCoeur d'Alene has a deeply rooted gun culture, with strong support for Second Amendment rights and open carry. In June 2020, during nationwide protests over racial justice following the murder of George Floyd, armed civilians patrolled the streets of downtown Coeur d'Alene, citing a desire to protect businesses from potential looting, although no violent incidents occurred.[55]

In 2022, tensions again rose when a Pride event in the city was disrupted by a group of armed protesters, many of whom were associated with the far-right group Patriot Front. Local law enforcement arrested several members of the group, charging them with conspiracy to riot, though the arrests were not directly related to firearm use. The presence of armed protesters at public events continues to spark debate about the balance between gun rights and public safety in Coeur d'Alene.[56]

Geography

editTopography

editAccording to the United States Census Bureau, the city has a total area of 16.08 square miles (41.65 km2), of which 15.57 square miles (40.33 km2) is land and 0.51 square miles (1.32 km2) is water.[57]

Coeur d'Alene is 30 miles (48 km) east of downtown Spokane, Washington, and 259 miles (415 km) east of Seattle.[58] The city is part of the Spokane–Coeur d'Alene combined statistical area and the Inland Northwest region, consisting of eastern Washington, northern Idaho, northwestern Montana, and northeastern Oregon.[59]

The city is located on the north shore of Lake Coeur d'Alene, near the outlet of the Spokane River, and is in the Northern Rockies ecoregion.[60][61] Lake Coeur d'Alene is a natural dam-controlled lake that is 25 miles (40 km) long and 1 mile (1.6 km) to 3 miles (4.8 km) wide and fed by the Coeur d'Alene and Saint Joe rivers.[62] Although the Post Falls Dam on the Spokane River near Post Falls controls the lake levels, the lake is usually kept at natural levels from January to June.[63] To the immediate southeast is Fernan Lake and to the northeast of the city is Hayden Lake and even further northeast in northern Kootenai County is Lake Pend Oreille, which is among the largest and deepest natural lakes in the western United States with a surface area of 85,960 acres (347.9 km2) and maximum depth of 1,152 feet (351 m).[60][64] These lakes, like others in the Spokane Valley and Rathdrum Prairie, were formed by the Missoula Floods, which ended 12,000 to 15,000 years ago.[65] The Coeur d'Alene Mountains of the Bitterroot Range rise to the east of the city to a maximum elevation of 7,352 feet (2,241 m) at Cherry Peak.[66]

The wooded lands east of the city, the Coeur d'Alene National Forest, have been designated for protection and management by the Idaho Panhandle National Forests. These thick forests include groves of ancient western redcedar and host over 300 wildlife species including woodland caribou, Canada lynx, grizzly bear, and wolves.[67][68] The large lakes in the Idaho panhandle attract birds on the Pacific Flyway, and bird watching is popular on Lake Coeur d'Alene, especially from November to February when bald eagles come annually to feed on the spawning kokanee.[69][70] The Cougar Bay Nature Preserve on the northeast portion of Lake Coeur d'Alene is the closest and most accessible nature preserve for wildlife viewing, as it is located a few minutes from downtown Coeur d'Alene.[71]

Environmental concerns have come as a result of upstream hardrock mining and smelting operations in the Silver Valley. The Coeur d'Alene Basin, including Lake Coeur d'Alene, is polluted with heavy metals such as lead and was designated a superfund site in 1983 that spans 1,500 square miles (3,884.98 km2) and 166 miles (267 km) of the Coeur d'Alene River.[72] The majority of the lake bed is covered in a layer of contaminated sediment and local health officials at the Panhandle Health District advise the lake's visitors to wash anything that has come into contact with potentially lead-laced soil or dust in the Coeur d'Alene River basin.[73]

Landscape

editClimate

editCoeur d'Alene has, depending on the definition, a dry-summer continental climate (Köppen Dsb) or a warm-summer Mediterranean climate (Csb), characterized by a cold, moist climate in winter, and very warm, dry conditions in summer.[74][75] The daily mean temperature ranges from 31.2 °F (−0.4 °C) in January and December to 70.1 °F (21.2 °C) in July.[76] Temperatures exceed 90 °F (32 °C) on 18.3 days per year, only occasionally reaching 100 °F (38 °C), and there may be several nights below 10 °F (−12 °C).[76] The average first and last freezes of the season are October 17 and April 28, respectively. The city straddles the border between USDA Plant Hardiness Zones 6B and 7A.[77] The Spokane–Coeur d'Alene area has many microclimates that can have different weather patterns and observations from the nearby official reporting stations used by the National Weather Service due to the diversity of the topography and other factors. For instance, northern Idaho experiences more precipitation in rain and snow than eastern Washington from weather systems originating from the Pacific Ocean because it is on the windward side of the Rocky Mountains.[78] Average annual rainfall is 25 inches (64 cm) and the average annual snowfall is 46 inches (120 cm).[79] Northern Idaho weather is influenced by both maritime and continental weather systems. Moist air masses from the coast are released as precipitation over the North Central Rockies forests, creating the North American inland temperate rainforest, and dry air masses from Canada and the Great Plains contribute to dry summer months.[80] Coeur d'Alene can have noticeably milder nights and cooler days due to the moderating effect on the climate of large bodies of water such as Lake Coeur d'Alene.[78]

| Climate data for Coeur d'Alene, Idaho (1991–2020 normals, extremes 1895-present) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °F (°C) | 60 (16) |

62 (17) |

73 (23) |

94 (34) |

98 (37) |

108 (42) |

108 (42) |

109 (43) |

102 (39) |

88 (31) |

71 (22) |

60 (16) |

109 (43) |

| Mean maximum °F (°C) | 49.4 (9.7) |

51.3 (10.7) |

62.7 (17.1) |

74.0 (23.3) |

83.6 (28.7) |

88.5 (31.4) |

96.1 (35.6) |

96.3 (35.7) |

89.1 (31.7) |

74.9 (23.8) |

58.4 (14.7) |

49.2 (9.6) |

97.7 (36.5) |

| Mean daily maximum °F (°C) | 36.2 (2.3) |

40.7 (4.8) |

48.4 (9.1) |

56.2 (13.4) |

65.8 (18.8) |

72.1 (22.3) |

82.8 (28.2) |

83.0 (28.3) |

73.7 (23.2) |

58.4 (14.7) |

44.2 (6.8) |

36.1 (2.3) |

58.1 (14.5) |

| Daily mean °F (°C) | 31.2 (−0.4) |

33.6 (0.9) |

39.5 (4.2) |

46.4 (8.0) |

55.1 (12.8) |

61.5 (16.4) |

70.1 (21.2) |

69.5 (20.8) |

61.0 (16.1) |

48.6 (9.2) |

37.9 (3.3) |

31.2 (−0.4) |

48.8 (9.3) |

| Mean daily minimum °F (°C) | 26.2 (−3.2) |

26.5 (−3.1) |

30.7 (−0.7) |

36.7 (2.6) |

44.3 (6.8) |

50.9 (10.5) |

57.3 (14.1) |

56.0 (13.3) |

48.3 (9.1) |

38.7 (3.7) |

31.6 (−0.2) |

26.3 (−3.2) |

39.5 (4.2) |

| Mean minimum °F (°C) | 10.8 (−11.8) |

13.5 (−10.3) |

19.0 (−7.2) |

27.7 (−2.4) |

33.3 (0.7) |

42.1 (5.6) |

48.1 (8.9) |

47.0 (8.3) |

37.6 (3.1) |

26.3 (−3.2) |

19.7 (−6.8) |

12.8 (−10.7) |

4.6 (−15.2) |

| Record low °F (°C) | −30 (−34) |

−27 (−33) |

−13 (−25) |

5 (−15) |

21 (−6) |

28 (−2) |

36 (2) |

32 (0) |

17 (−8) |

2 (−17) |

−13 (−25) |

−26 (−32) |

−30 (−34) |

| Average precipitation inches (mm) | 3.21 (82) |

2.11 (54) |

2.68 (68) |

1.91 (49) |

2.14 (54) |

2.17 (55) |

0.73 (19) |

0.77 (20) |

0.81 (21) |

2.02 (51) |

3.34 (85) |

3.47 (88) |

25.36 (644) |

| Average snowfall inches (cm) | 10.0 (25) |

4.1 (10) |

2.2 (5.6) |

0.1 (0.25) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.2 (0.51) |

2.1 (5.3) |

9.3 (24) |

28.0 (71) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 0.01 in) | 14.4 | 11.1 | 12.6 | 11.3 | 11.1 | 9.1 | 3.8 | 3.5 | 6.0 | 11.1 | 14.8 | 13.2 | 122.0 |

| Average snowy days (≥ 0.1 in) | 4.5 | 2.3 | 1.3 | 0.2 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 1.3 | 4.4 | 14.1 |

| Source: NOAA[76][81] | |||||||||||||

Cityscape

editNeighborhoods

editAs Coeur d'Alene has grown from a fort town, different neighborhoods and suburbs have grown around it.[82] The downtown city center of Coeur d'Alene is in the southeast of the urban area as the presence of Hayden Lake and Lake Fernan and the Coeur d'Alene mountains inhibit development to the east and Lake Coeur d'Alene and the Spokane River limit development to the south and southwest. Historic additions from the early 1900s were added close to the city center a few blocks from downtown, such as on East Sherman Avenue, East Lakeshore Drive near Sanders Beach, and near present-day City Park.[83] Today, the city has many neighborhoods, the largest being Coeur d'Alene city center, Post Falls and Hayden. The Coeur d'Alene city center has several parks and attractions and as a community gathering place, it has heavy foot traffic on fair weather summer weekends.

The largest building in the city, the 216-foot (66 m) Coeur d'Alene Resort Lake Tower, is in the city center. The downtown area is of increasing interest to higher density multifamily apartment and condominium-type developments to cope with the growth in housing demand and due to a lack of space and concerns about urban sprawl.[84][85]

Investment in residential and retail development has been intensive along the Interstate 90 corridor and has made Post Falls near the Washington state line become Kootenai County's second largest city. Due to its central location between Spokane and Coeur d'Alene, the city is host to a growing list of retail stores and is considered a bedroom community of Spokane.

The historic Post Falls Dam and surrounding Falls Park on the Spokane River is a local landmark. Hayden is the third largest city in the Coeur d'Alene metropolitan area, and it is known for the eponymous Hayden Lake that was once the historic center of the community. The shores of the lake are filled with summer cabins and large mansions. The historic Hayden Lake Country Club, which lies at the center of the Hayden Lake community, was built in 1907 along with a rail connection with the Spokane and Inland Empire Railroad that same year, which brought in many tourists to the resort and Honeysuckle Beach.[86]

With the rising use of the automobile, the center of town shifted away from the lake and railroad and reoriented toward Government Way.[87]

Demographics

edit| Census | Pop. | Note | %± |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1890 | 491 | — | |

| 1900 | 508 | 3.5% | |

| 1910 | 7,291 | 1,335.2% | |

| 1920 | 6,447 | −11.6% | |

| 1930 | 8,297 | 28.7% | |

| 1940 | 10,049 | 21.1% | |

| 1950 | 12,198 | 21.4% | |

| 1960 | 14,291 | 17.2% | |

| 1970 | 16,228 | 13.6% | |

| 1980 | 19,913 | 22.7% | |

| 1990 | 24,563 | 23.4% | |

| 2000 | 34,514 | 40.5% | |

| 2010 | 44,137 | 27.9% | |

| 2020 | 54,628 | 23.8% | |

| 2022 (est.) | 56,733 | [5] | 3.9% |

| U.S. Decennial Census[88] 2020 Census[4] | |||

2020 census

editAs of the census of 2020, there were 54,628 people and 22,699 households residing in the city. Coeur d'Alene and its Metropolitan Statistical Area (MSA), which consists of Kootenai County, have been combined by the Census Bureau into the Spokane–Coeur d'Alene Combined Statistical Area (CSA) where it is the third-largest polity after Spokane and its largest suburb, Spokane Valley.[89] The population of the CSA was 745,213 in 2020.[90] The principal cities in the CSA are separated by suburbs that largely follow the path of Spokane Valley and Rathdrum Prairie. The City of Coeur d'Alene has opted not to voluntarily merge with the Spokane MSA and to remain a distinct metropolitan area.[91] According to Office of Management and Budget (OMB) guidelines, the two MSAs will automatically be combined by the OMB when the employment interchange exceeds 25 percent; in 2011, 18 percent of residents commuted between Spokane and Kootenai counties for work.[91]

2010 census

editAs of the census of 2010, there were 44,137 people, 18,395 households, and 10,813 families residing in the city. The population density was 2,834.7 inhabitants per square mile (1,094.5/km2). There were 20,219 housing units at an average density of 1,298.6 per square mile (501.4/km2). The racial makeup of the city was 93.8% White, 0.4% African American, 1.2% Native American, 0.8% Asian, 0.1% Pacific Islander, 0.9% from other races, and 2.8% from two or more races. Hispanic or Latino people of any race were 4.3% of the population.

There were 18,395 households, of which 29.9% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 42.2% were married couples living together, 11.6% had a female householder with no husband present, 5.0% had a male householder with no wife present, and 41.2% were non-families. 31.4% of all households were made up of individuals, and 12.1% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.33 and the average family size was 2.92. The median age in the city was 35.4 years. 22.9% of residents were under the age of 18; 11.6% were between the ages of 18 and 24; 26.7% were from 25 to 44; 24% were from 45 to 64; and 14.6% were 65 years of age or older. The gender makeup of the city was 48.6% male and 51.4% female.

Religion

editAccording to the 2010 Metro Area Membership Report of the Association of Religion Data Archives, the denominational affiliations of the Coeur d'Alene MSA (Kootenai County) are 60,657 Evangelical Protestant, 3,064 Mainline Protestant, 7,597 Catholic, 162 Orthodox, 8,492 Other, and 58,522 Unclaimed.[92] Idaho is part of a region called the Unchurched Belt, a region in the Northwestern United States that has historically low rates of religious participation. The evangelical Christian community has been growing with the overall population and there have been instances of whole congregations moving to the area from out of state.[49] The evangelical Christian Real Life Ministries church located in Post Falls was the 13th fastest growing church in the nation in 2007.[93]

Many new residents are retirees seeking lower cost of living and traffic; the number of residents aged 65 years and older doubled from 2001 to 2019 according to the Idaho Department of Labor.[94]

Crime

edit| Coeur d'Alene | |

|---|---|

| Crime rates* (2022) | |

| Violent crimes | |

| Homicide | 1 |

| Rape | 54 |

| Robbery | 14 |

| Aggravated assault | 108 |

| Total violent crime | 177 |

| Property crimes | |

| Burglary | 72 |

| Larceny-theft | 478 |

| Motor vehicle theft | 36 |

| Arson | 9 |

| Total property crime | 595 |

Notes *Number of reported crimes per 100,000 population. 2022 population: 56,733 Source: 2022 FBI UCR Data | |

According to the National Incident-Based Reporting System, the Coeur d'Alene metro area (Kootenai County) crime rate per 100,000 population was 4,864 in 2018, which was lower than the Idaho state average of 5,032.[95] The county has a property crime rate of 12.88 and a violent crime rate of 1.59 per 1,000 people in the 2018 Uniform Crime Reports summary, which is lower than the Idaho state average of 14.61 and 2.27 respectively.[96][97] According to NeighborhoodScout's methodology, the city has a crime index of 24, meaning it is safer than 24 percent of US cities, and has a property and violent crime rate slightly above the Idaho state average but still below the national median in both categories.[98]

Economy

editHistorically, the economy of Coeur d'Alene was built and based on mining and logging and the Coeur d'Alene Mining District has been one of the world's most productive mining districts.[99] However, after mining and logging diminished in importance in the 1940s, tourism has come to be the main influence in the local economy ever since. The city has become a major tourist attraction, being at the heart of north Idaho's Lake Country where people partake in water sports and activities such as wake boarding, paddleboarding, sailing, parasailing, jet skiing, kayaking, fishing and other lake recreation.[100] In addition to the natural attractions and parks, the Coeur d'Alene area has two major resorts on the lake, the Coeur d'Alene Resort and the WorldMark Arrow Point resort directly across the lake in Harrison near the community of Eddyville as well as the Coeur d'Alene Casino in Worley, and the Northwestern United States' largest theme park in the Silverwood Theme Park in Athol.[101][102][103] There are three major ski resorts within a short driving distance, Silver Mountain Resort in Kellogg, Lookout Pass Ski and Recreation Area at Lookout Pass near Mullan, and Schweitzer Mountain Ski Resort in Sandpoint.[104] Tourism and hospitality related jobs employed over 10,000 people in north Idaho in 2010.[105]

Coeur d'Alene is the healthcare, educational, media, manufacturing, retail and recreation center for north Idaho. Coeur d'Alene's retail has expanded greatly in recent years with the opening of new stores and entertainment venues; the Silver Lake Mall, which is the largest in North Idaho, was opened in 1989.[106] Coeur d'Alene's Village at Riverstone development along Northwest Boulevard houses a park, amphitheater, 14-theater Regal Cinemas, a Hampton Inn, condominiums, restaurants, and local retailers.[107]

Companies that have their head offices in Coeur d'Alene include mining company and owner of the Lucky Friday mine in Mullan, Hecla Mining and the U.S. operations of Canada-based restaurant Pita Pit.[108][109] A knife manufacturer, Buck Knives, is the most recognizable brand name in the area, where they relocated the head office and factory from San Diego to the Coeur d'Alene suburb of Post Falls in 2005.[110] Construction company and roller coaster manufacturer, Rocky Mountain Construction is based in Hayden.[111] In 2017, the Coeur d'Alene metropolitan area had a gross metropolitan product of $5.93 billion.[112] The Coeur d'Alene metropolitan area has a workforce of 80,000 people and an unemployment rate of 6.8% (as of June 2020); the largest sectors for non-farm employment are trade, transportation, and utilities, government, and education and health services as well as leisure and hospitality.[113]

The average commute to work is 18.5 minutes.[114] Commuting across the state line into Washington is not uncommon. A concern for the city is that the rising minimum wage and salary differential between Washington and Idaho will cause local personnel shortages.[115] In 2011, the Idaho state median hourly wage was $14.51 according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics.[116]

Arts and culture

editArts and theater

editThe Coeur d'Alene area has a growing arts scene. The community has a symphony and theater productions from professional and community groups. The city has several art galleries, almost all displaying art located in the walkable downtown area along Sherman Avenue, Coeur d'Alene's main street.[117] Among the most prominent of these galleries is The Art Spirit Gallery.[118] Art can also be seen outside for free.[119] Since 1999, the City of Coeur d'Alene has had a funding mechanism for public art where 1.33 percent of the total cost of all eligible above-ground capital improvement projects is earmarked to fund art in public places.[120]

In the musical arts, the Coeur d'Alene Symphony traces its roots to the late 1970s as a class at North Idaho College.[121] The symphony performs an annual free concert for the community on Labor Day in Coeur d'Alene City Park and also performs during the summer. Street artists and musicians frequent Sherman Square performing for pedestrians. Theater arts are provided by the professional Coeur d'Alene Summer Theatre group and the community theater company, Lake City Playhouse.[122] The city's primary performing arts venues are the Schuler Performing Arts Center within Boswell Hall at North Idaho College and the Kroc Center.[123][124]

Museums

editThe Museum of North Idaho located in downtown Coeur d'Alene chronicles the history of the region. The museum was established in July 1973[125] and permanent exhibits include "Schitsu'umsh, 'The People Who Were Discovered Here'", which explores the lives of the Coeur d'Alene people; "The Mullan Road", which commemorates Idaho's first road through the Fourth of July Pass; "The Scandinavians Settled Here", which examines the Nordic influences on Coeur d'Alene; and "Steamboats", which displays artifacts and photographs of the steamboats that used to cruise the lake.[126] The museum does walking tours of the Fort Sherman grounds and also rents out the Fort Sherman chapel, the oldest building in the city as a wedding venue.[127][128]

Events and activities

editMany of the community events and activities in Coeur d'Alene occur during the warm summer months and they often take place by the lake. Annual events include the Fourth of July Festival and the Holiday Light Show that begins at the end of November. Coeur d'Alene has been known for hosting big Fourth of July celebrations since its early days as a fort town. The Fourth of July Festival usually includes a parade down Sherman Avenue, food and craft vendors, carnival rides, and live music and entertainment.[129] Many watch the fireworks by the waterfront and beach; the Coeur d'Alene resort offers fireworks cruises that depart from Independence Point. In the winter, the Holiday Light Show festivities begin at the end of November and the lights are on display until January 1. The event also begins with a parade down Sherman Avenue and ends with a fireworks show; the resort's light show features over 1.5 million bulbs, and the resort offers "Journey to the North Pole" cruises.[130][131] Another event in the winter months that often gets media attention is the Polar Bear Plunge every year on January 1 at noon, where event participants run into the cold waters of Lake Coeur d'Alene at Sanders Beach.[132]

One of the most well-attended events in the region combines Art on the Green, the Street Fair, and Taste of Coeur d'Alene, which are all held on the first weekend in August on the North Idaho College campus, downtown Coeur d'Alene, and City Park.[133] Art on the Green is an outdoor arts and crafts festival, Street Fair is a shopping festival, and the Taste of Coeur d'Alene is a food festival; the combined annual attendance is about 60,000 people.[134] Other notable events include Brewfest and the North Idaho State Fair.[134]

Sports

editCoeur d'Alene has become a destination for golf enthusiasts.[135][136] The city is home to five golf courses and there are another eight more within 20 miles (32 km).[137] Coeur d'Alene Resort Golf Course is considered one of the best resort courses in the United States.[138] Its 14th hole features the world's only movable floating green.[139][140] There is also the Circling Raven Golf Club at the Coeur d'Alene Casino resort,[141] as well as several other private courses nearby, such the Tom Fazio-designed Gozzer Ranch.[142][143]

Coeur d'Alene hosts some sporting events, and the event that receives the most attention is most likely the Ironman Coeur d'Alene. The Ironman Triathlon alternates between full- and half-distance Ironman events on a rotating basis from year to year.[144] The course takes athletes through a 2.4-mile (3.9 km) double-loop swim in Lake Coeur d'Alene before transitioning to a 112-mile (180 km) double-loop bike course that is routed along the lake and then through the countryside, ending in a 26.2-mile (42.2 km) multiple-loop run through McEuen Park to a finish in downtown on Sherman Ave.[145] Other less intense and rigorous athletic events in town include the 15–108 mi (24–174 km) Coeur d'Fondo bike race[146] and the Coeur d'Alene Crossing, a 2.4-mile (3.9 km) swimming challenge in which participants attempt to cross the lake.[147] The Coeur d'Alene marathon is held annually at the end of May on the North Idaho Centennial Trail.[148]

In amateur baseball, Coeur d'Alene fields a team in the American Legion Baseball league, the CDA Lumbermen.[149] In high school team sports, there is an annual rivalry game between the Coeur d'Alene High School Vikings and Lake City High School Timberwolves called the "Fight for the Fish".[150] The schools are the only two public high schools in the city and both compete in Idaho's Inland Empire League. The city is also home to Kyle Manzardo, professional baseball player for the Cleveland Guardians

Parks and recreation

editThe natural environment is among the chief attractions in the Coeur d'Alene area. The biggest natural attractions and parks include Tubbs Hill, City Park and Beach, and McEuen Park, all near downtown. Tubbs Hill is a 120-acre (49 ha) park that is bordered by downtown Coeur d'Alene and McEuen Park to the north and the by Lake Coeur d'Alene on the south, east, and west sides.[151] The park features a somewhat rugged 2.2-mile (3.5 km) interpretive trail that offers views of the lake and the city.[152] People often cliff jump into the lake from outcroppings in the park. City Park occupies 17 acres (6.9 ha) in total along the lake shore near downtown and features 16 acres (6.5 ha) of beach with a tree lined promenade, beach volleyball courts, basketball courts, public drinking, restroom, and shower facilities, picnic tables, and a large picnic shelter for events, and a Fort Sherman themed playground for children.[152][153] McEuen Park, which reopened in 2014 after a remodel, is a 22.5-acre (9.1 ha) park just north of Tubbs Hill that has a large playground, children's climbing rock, splash pad, two tennis/pickleball courts, four basketball courts, and an off leash dog park.[152] It also features a large pavilion and grassy amphitheater with concessions and restrooms for hosting large events as well as a boat launch and mooring facilities.[52][154] Other recreation facilities include the Kroc Center, located near Ramsey Park just north of the Village at Riverstone, a multi-use venue with pool facilities and a fitness and recreation center.[155]

The North Idaho Centennial Trail passes through the city.

Government

editThe community operates on a mayor–council government, where the mayor and the six councilors are each elected to four-year terms and the mayor leads the city council meetings on the first and third Tuesday of each month at Coeur d'Alene City Hall.[156][157] The city is also the county seat of Kootenai County, Idaho.[158]

At the state level, The City of Coeur d'Alene is within Idaho Legislative District 2 and Idaho Legislative District 4 for the Idaho House of Representatives and Idaho Senate. At the federal level, north Idaho is within Idaho's 1st congressional district and represented by Russ Fulcher in the United States House of Representatives and the state of Idaho by Mike Crapo and James Risch in the United States Senate.[159][160]

Coeur d'Alene, like the state of Idaho as a whole, is known for its conservative politics.[161] The city and Kootenai County vote reliably conservative, and races at the federal and state level are often noncompetitive; local county and city partisan races are sometimes even uncontested.[162] The changing demographics of the county and region have altered the political landscape of the community and can be viewed as part of a nationwide ideological polarization trend.[49] North Idaho had once been made up of largely progressive districts populated by a significant proportion of union laborers who worked the mines in the Silver Valley; these districts moderated, particularly in the 1980s, after mine and mill closures and union busting, and they had more competitive elections until the late 20th century.[49][162][163][164] Coeur d'Alene is among a small group of cities in the United States that has elected a socialist mayor; they elected John T. Wood, a Socialist Party of America member, to office in 1911 on a campaign platform of clean water, better health and sanitation standards, and anti-corruption.[165] Since the high-growth period beginning in the 1990s, continuing outmigration of conservatives from the west coast states has made elections in the two-party system less competitive over time as the newer residents see the city as a place that represents their social and political values, which are sometimes more conservative than the city as a whole.[162][164] Many of the new migrants to the state of Idaho came from California, which accounted for over half the net in-migration between 1992 and 2000 and three of the top four counties that had out-migration to Kootenai County were from the birthplace of modern American conservatism in southern California–San Diego, Los Angeles, and Orange.[49]

Education

editLibrary services for the city of Coeur d'Alene are provided by two public libraries, the Coeur d'alene Public Library in downtown and the Lake City Public Library near Lake City High School.[166][167] The Community Library Network maintains seven libraries in the wider communities in Kootenai and Shoshone counties, including branches in Post Falls, Hayden, Rathdrum, Spirit Lake, Athol, and Harrison.[168] Public library services in the area trace their roots to the Coeur d'Alene Women's Club in October 1904 and its operations and funding responsibilities were taken over by the city in May 1909.[169]

The Coeur d'Alene School District serves around 11,000 students in 18 schools, including two traditional high schools, an alternative high school, three middle schools, eleven elementary schools, and a dropout retrieval school.[170] The first high school in the city, Coeur d'Alene High School, had its first building to house the students completed in 1904[171] and a second public high school, Lake City High School, was opened in 1994. District students who qualify are also eligible for dual enrollment with North Idaho College and the University of Idaho. The district also has magnet schools that focus on specific curricula, such as the Sorensen Magnet School of the Arts and Humanities and Ramsey Magnet School of Science elementary schools and the Fernan STEM Academy, offering a STEM focus.[172][170] The district is the sixth-largest in the state and second-largest employer in Kootenai County.[173] Coeur d'Alene also has a charter school, the Coeur d'Alene Charter Academy.[174] Private and parochial schools augment the public school system, such as the PK-8 grade Roman Catholic Holy Family Catholic School and the PK-8 grade Seventh-day Adventist Lake City Academy.[175] Private schools that offer a full high school curriculum include the PK-12 grade Classical Christian Academy and the 1–12 grade North Idaho Christian School which are both non-denominational ASCI-accredited Christian schools located in Hayden.[176][177]

Postsecondary education is fulfilled by North Idaho College, a public community college founded in 1933 as the Coeur d'Alene Junior College in downtown Coeur d'Alene on the former site of Fort Sherman.[178] The college has an enrollment of over 5,000 students and has outreach branches in Kellogg, Sandpoint, and Bonners Ferry.[179] The University of Idaho has a Coeur d'Alene presence and has a research park in the area.[180]

Media

editCoeur d'Alene is part of the Spokane television and radio media market and receives broadcasts in the Pacific Time Zone. Coeur d'Alene is the city of license for some television and radio stations in the broadcast area, such as Idaho Public Television station, KCDT.[181] In print media, Coeur d'Alene is also covered by Spokane's major daily newspaper, The Spokesman-Review, but the city has its own daily newspaper, the Coeur d'Alene Press, which covers issues in North Idaho and has an estimated circulation of about 17,300.[182] The publication was founded in 1892 by Joseph T. Scott and printed its first issue on February 20 of that year.[183] The newspaper is among the properties of the Hagadone Corporation.[182]

Infrastructure

editTransportation

editRoads and highways

editIn Coeur d'Alene, the city roads are oriented in the four cardinal directions, with roads going north–south being designated as "streets" and roads going east–west as "avenues". Sherman Avenue divides the streets into north and south, and Government Way divides the avenues into east and west. Major east–west thoroughfares include Sherman Avenue and Harrison Avenue and major north–south thoroughfares include U.S. Route 95 (US 95), Government Way, 15th Street, and Ramsey Street.[184][185] Coeur d'Alene is accessed from Interstate 90 (I-90) at exits 11 through 15.[186] Not too far to the east on I-90 is the Fourth of July Pass and further east near the Montana border is Lookout Pass that traverse the Rocky Mountains near Mullan, Idaho.[187] The route of the Interstate east of Coeur d'Alene closely mirrors that of the old Mullan Road, although I-90 crosses the Fourth of July Pass two miles (3.2 km) south of John Mullan's passage, which was carved out using pickaxes and shovels on July 4, 1861, and is now listed on the National Register of Historic Places and marked by a monument.[16][188] Before the construction of I-90, the city was served by US 10, which ran through downtown; this route is now Northwest Boulevard and Sherman Avenue. The former US 10, between I-90 exits 11 and 15, is now designated as I-90 Business. I-90 was completed on October 14, 1960, and dedicated by Governor Robert E. Smylie 10 days later as the state's first major Interstate Highway project to be completed.[189] Major state highways in the area include State Highway 41 (SH 41) and US 95. SH 41 has its southern terminus in Post Falls and is routed from I-90 northward to the Newport, Washington area, where it is in the vicinity of US 2, and US 95 runs north to south across the whole of western Idaho, connecting the city with Sandpoint to the north and Moscow, Lewiston, and eventually Boise to the south.[186] Originally an exclusively in-state highway when it was proposed by the United States Numbered Highway System in 1925, spanning from the Canadian border to Payette, it is significant for connecting the long-disconnected northern panhandle to the rest of the state; prior to the construction of US 95, one would have to travel through Washington and Oregon for passage to avoid the mountainous topography.[190] The portion of its route that it shares with US 2 is a National Scenic Byway and part of the International Selkirk Loop.[186] In Coeur d'Alene, US 95 runs north to south, crossing the Spokane River and serving as an arterial street for the suburbs to the north.[184]

The greater Coeur d'Alene area is almost entirely dependent upon private automobiles for transportation, the city has a Walk Score of 36, indicating most errands require a car.[191] Combined with the city's rapid growth since 1990, relative congestion now occurs on a significant portion of the area highways, notably U.S. 95 between Northwest Blvd. north to Hayden.[192] The average commute to work is 18.5 minutes.[114]

Public transportation

editPublic transportation played a significant role in Coeur d'Alene's early growth as a tourist destination. When an interurban electric railroad line was completed in 1903 from Spokane to the city, Inland Northwest residents often flocked to Lake Coeur d'Alene to enjoy being on the lake and going on steamboat cruises and other activities.[193] The interurban electric line would later become the Spokane and Inland Empire Railroad. The steamboats on Lake Coeur d'Alene were not only used to transport goods such as ore and timber, but also people. More steamboats operated on Lake Coeur d'Alene than on any other lake west of the Great Lakes, and there were intense rivalries between the steamboat lines.[194] The electric railroad and steam navigation on Lake Coeur d'Alene lasted until the late 1930s.[195][c]

Free public bus service is available to area residents, provided by Citylink.[197] Citylink buses operate in the urbanized area of Kootenai County, leaving the Riverstone Transfer Station main hub every hour, seven days a week, including holidays. Buses are wheelchair-accessible and can transport up to two bicycles.[198] The bus system has four separate routes:[197][199] Urban Route B which serves Post Falls, Hayden and West Coeur d'Alene, Urban Route C which serves Downtown Coeur d'Alene, Fernan and Hayden, Rural Route, which serves the towns of Worley, Plummer, Tensed, and De Smet, and the Link Route, which connects the two transfer stations at Riverstone and Worley. Extension of Spokane Transit Authority service into Idaho, mainly an hourly express bus to and from Coeur d'Alene, originally proposed as part of the 2015 "STA Moving Forward" ballot measure, is expected to commence in 2025.[200][201]

Intercity bus service to the city is provided by Jefferson Lines.[202]

Passenger rail

editCoeur d'Alene does not have a passenger railroad station. The closest Amtrak stations are Spokane and Sandpoint, both of which are served by Amtrak's Empire Builder.[203]

Airports

editThe closest major airport serving Coeur d'Alene and North Idaho is Spokane International Airport, which is served by six airlines and is 40 miles (64 km) to the west in Spokane, Washington.[204] The Coeur d'Alene Airport – Pappy Boyington Field (KCOE) serves as a general aviation airport in Hayden, north of the city near U.S. 95.[205] The airport was built by the U.S. Army Air Corps in 1942 as a fighter and light bomber training base.[206] The Coeur d'Alene Airport was designated as an alternate airport to Weeks Field (now the site of the Kootenai County Fairgrounds) in the event of an Axis invasion; the Weeks Field airport was also used to train pilots during World War II.[207] It is named in honor of World War II flying ace and North Idaho native, Gregory "Pappy" Boyington.[208]

Near the marina on Lake Coeur d'Alene is the Brooks Seaplane Base (S76), which is a city-owned, public-use seaplane base for general aviation. It is used mostly for air taxi purposes to conduct tours of Lake Coeur d'Alene and Lake Pend Oreille.[209]

Utilities

editThe city of Coeur d'Alene provides billing services for municipal water, sewer and stormwater management, street lighting, garbage collection, and recycling; Kootenai Electric Cooperative provides power and Avista Utilities provides both power and natural gas services in the area.[210][211] The city draws its water supply from the Spokane Valley–Rathdrum Prairie Aquifer. Telecom services such as television, internet, and telephone service are provided by vendors including Frontier Communications, Spectrum, Time Warner, and TDS Telecom.[210]

The Post Falls hydroelectric dam on the Spokane River was built in 1906 and has a generation capacity of 14.75 megawatts.[212]

Healthcare

editKootenai Health is the primary medical center serving the Coeur d'Alene and North Idaho communities. The 329-bed community hospital is a Level III trauma center[213][214] and is the largest employer in Kootenai County.[215] Coeur d'Alene also has a Veterans Affairs Community Based Outpatient Clinic (CBOC), the North Idaho CBOC, which has the Mann-Grandstaff VA Medical Center in Spokane as a parent facility.[216] Public health programs and services for Idaho's five northernmost counties are administered by the Panhandle Health District, one of seven health districts in the state, with a local office in Hayden.[217]

Police

editThe Coeur d'Alene Police Department was established in 1887, shortly after Coeur d'Alene was incorporated as a town; one of the first official acts the Board of Trustees took was to appoint a Town Marshal.[20] The police department has 103 police officers as of September 2020.[218] In addition to the officers on staff, the department has a program called Officers Without Legal Standing (OWLS), which consists of retired law enforcement officers of various backgrounds from California who render assistance and aid as unpaid volunteers.[219][220] Coeur d'Alene and North Idaho have been favored retirement destinations for former California law enforcement for decades, the trend being reported on as early as 1986 by the Los Angeles Times.[221][222][219] By the end of the 1990s, the number of retired California police officers in North Idaho numbered over 500; former LAPD detective Mark Fuhrman is among its residents.[49]

Sister cities

editCoeur d'Alene has one sister city, which is the Canadian city of Cranbrook, British Columbia.[223]

See also

editNotes

edit- ^ Lewis and Clark noted the likely first contact between the Coeur d'Alene people and European Americans in a trade encounter at a Nez Perce camp on their expedition in 1805; along with trade goods, the trappers unwittingly brought diseases that decimated the native population by about 80 percent.[9]

- ^ The U.S. government decided to close Fort Sherman and build Fort George Wright in Spokane in part due to the persistent flooding of the banks on Lake Coeur d'Alene.[30]

- ^ The popularity and convenience of the automobile and better road infrastructure led to the decline in other modes of transportation.[196] Some steamboats were deliberately set ablaze for Fourth of July celebrations in the late 1930s.[195]

References

edit- ^ Oliveria, Dave F. (May 24, 2011). "Walla Walla Slogan Among Worst". The Spokesman-Review. Retrieved August 8, 2020.

- ^ "2020 U.S. Gazetteer Files". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved July 24, 2022.

- ^ a b U.S. Geological Survey Geographic Names Information System: Coeur d'Alene, Idaho

- ^ a b c "Explore Census Data". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved January 15, 2024.

- ^ a b "City and Town Population Totals: 2020-2022". United States Census Bureau. January 15, 2024. Retrieved January 15, 2024.

- ^ "Coeur d'Alene". The American Heritage Dictionary of the English Language (5th ed.). HarperCollins. Retrieved May 16, 2019.

- ^ "Coeur d'Alene". Lexico US English Dictionary. Oxford University Press. Archived from the original on August 29, 2022.

- ^ "Coeur d'Alene". Merriam-Webster.com Dictionary. Merriam-Webster. Retrieved May 16, 2019.

- ^ a b c d e f g Dahlgren et al. (2009), p. 2

- ^ a b c d e f Frey, Rodney. "Coeur d'Alene (Schitsu'umsh)". American Indians of the Pacific Northwest collection, University of Washington Libraries. University of Washington. Retrieved July 17, 2013.

- ^ a b c d Singletary (2019), p. VII

- ^ Walker (1999), p. 60

- ^ a b c Dahlgren et al. (2009), p. 3

- ^ Frey (2001), pp. 79–81

- ^ Dahlgren et al. (2009), p. 17

- ^ a b Johnson, Randall A. (November 5, 2009). "The Mullan Road: A Real Northwest Passage". People's History collection. The Pacific Northwesterner, Vol. 39, No. 2 (1995). HistoryLink. Retrieved November 23, 2021.

- ^ a b c d Singletary (2019), p. 1

- ^ Singletary (2019), p. 11

- ^ Singletary (2019), p. 13

- ^ a b Singletary (2019), p. 14

- ^ Langdon (1908), p. 12

- ^ a b c d Clark, Earl (August 1971). "Shoot-Out In Burke Canyon". American Heritage. 22 (5). Retrieved October 14, 2020.

- ^ Langdon (1908), p. 13

- ^ Lukas (1997), p. 111

- ^ Langdon (1908), p. 16

- ^ Schwantes (1996), p. 320

- ^ Carlson (1983), pp. 53–54

- ^ Carlson (1983), pp. 91–92, p. 119

- ^ a b c d Singletary (2019), p. 27

- ^ Singletary (2019), p. 21

- ^ Singletary (2019), pp. 35–38

- ^ Singletary (2019), p. 49

- ^ Singletary (2019), p. 79, p. 93

- ^ Singletary (2019), p. 93

- ^ Singletary (2019), pp. 99–104

- ^ Singletary (2019), p. 99

- ^ Singletary (2019), p. 113

- ^ Singletary (2019), p. 27, pp. 31–32

- ^ Singletary (2019), pp. 137–138

- ^ Singletary (2019), p. 141

- ^ a b Singletary (2019), p. 147

- ^ Singletary (2019), p. 173

- ^ a b Singletary (2019), p. 176

- ^ Egan, Timothy (September 21, 1986). "NATIONAL NOTEBOOK: Coeur d'Alene, Idaho; Wilderness Luxury". The New York Times. Retrieved August 8, 2020.

- ^ a b c d Struck, Doug (August 31, 2017). "The Idaho town that stared down hate – and won". The Christian Science Monitor. Retrieved August 8, 2020.

- ^ a b Glionna, John M. (August 8, 1994). "Welcome to the Potato State—Now Go Home : Idaho: Californians fleeing big-city problems have been met with resentment by their new neighbors". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved August 8, 2020.

- ^ Verhovek, Sam Howe (September 9, 2000). "PUBLIC LIVES; In a Verdict, a Sign That His Town Is No Haven for Hate". The New York Times. Retrieved September 19, 2020.

- ^ Singletary (2019), p. 194

- ^ a b c d e f Crane-Murdoch, Sierra (May 20, 2013). "How right-wing emigrants conquered North Idaho". High Country News. 8 (45). Retrieved August 8, 2020.

- ^ a b Erickson, Keith (May 10, 2018). "On a roll at Silverwood". Spokane Journal of Business. Retrieved January 9, 2021.

- ^ Dubin, Zan (September 17, 1989). "Venerable Corkscrew: End of a Long Ride: Before Knott's Historic Roller Coaster Is Carted Off to Idaho Park, Many Pause to Attest to Its Thrills". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved January 9, 2021.

- ^ a b Maben, Scott (April 26, 2014). "Contentious makeover of McEuen Park in CdA set for partial opening". The Spokesman-Review. Retrieved August 9, 2020.

- ^ a b Criscione, Wilson (January 11, 2018). "In North Idaho, leaders brace for rapid population growth". Inlander. Retrieved August 8, 2020.

- ^ "Utah shaken after experiencing racism near hotel". ESPN.com. March 26, 2024. Retrieved March 26, 2024.

- ^ Blanchard, Nicole (June 3, 2020). "Armed residents patrol Coeur d'Alene as George Floyd protests continue across U.S." Idaho Statesman. Retrieved October 17, 2024.

- ^ Caldwell, Leah (June 11, 2022). "31 Patriot Front members arrested near Idaho Pride event, charged with conspiracy to riot". The Washington Post. Retrieved October 17, 2024.

- ^ "US Gazetteer files 2010". United States Census Bureau. Archived from the original on July 2, 2012. Retrieved December 18, 2012.

- ^ "How Far is it Between". Free Map Tools. Retrieved July 29, 2020.

- ^ "Inland Empire". Merriam-Webster Dictionary. Retrieved July 29, 2020.

- ^ a b TopoView: The National Map (GeoPDF) (Topographic map). 1:24,000. 7.5 Minute Series. Reston, VA: United States Geological Survey. Retrieved October 9, 2020.

- ^ "Draft: Level III and IV Ecoregions of the Northwestern United States". U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. May 15, 2002. Retrieved July 29, 2020.

- ^ Schultz, Jule (August 14, 2018). "Coeur d'Alene Lake: The Good, The Bad, and The Ugly". Spokane Riverkeeper. Retrieved August 12, 2020.

- ^ "Is Coeur d'Alene Lake a Reservoir or Lake?". Avista Corporation. Retrieved August 12, 2020.

- ^ "Lake Pend Oreille Idaho". Idaho Washington Aquifer Collaborative. Retrieved October 9, 2020.

- ^ Breckenridge, Roy M. (May 1993). Glacial Lake Missoula and the Spokane Floods (PDF) (Report). GeoNotes. Vol. 26. Idaho Geological Survey. Archived from the original (PDF) on April 26, 2012. Retrieved November 29, 2011.

- ^ "Cour d'Alene Mountains". Peakbagger.com. Retrieved August 8, 2020.

- ^ "Our Forests: Idaho Panhandle National Forest". National Forest Foundation. Retrieved November 20, 2021.

- ^ "Wildlife of the Idaho Panhandle National Forests". United States Forest Service. Retrieved November 20, 2021.

- ^ "Lake Coeur d'Alene Eagle Watch". Bureau of Land Management. Retrieved August 8, 2020.

- ^ Hardy, Madison (July 12, 2020). "Wildlife lovers enjoy osprey cruise on Lake Coeur d'Alene". Coeur d'Alene Press. Retrieved September 19, 2020.

- ^ "Cougar Bay Preserve". The Nature Conservancy. Retrieved September 19, 2020.

- ^ "Superfund Site: Bunker Hill Mining & Metallurgical Complex". U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. Retrieved October 29, 2020.

- ^ Benson, Emily (June 24, 2019). "A dangerous cocktail threatens the gem of North Idaho". High Country News. 11 (51). Retrieved October 29, 2020.

- ^ Beck, Hylke E.; Zimmermann, Niklaus E.; McVicar, Tim R.; Vergopolan, Noemi; Berg, Alexis; Wood, Eric F. (October 30, 2018). "Present and future Köppen-Geiger climate classification maps at 1-km resolution". Scientific Data. 5: 180214. Bibcode:2018NatSD...580214B. doi:10.1038/sdata.2018.214. ISSN 2052-4463. PMC 6207062. PMID 30375988.

- ^ "Coeur d'Alene Climate". Climate-Data.org. Retrieved August 8, 2020.

- ^ a b c "U.S. Climate Normals Quick Access – Station: Coeur d'Alene, ID". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved March 8, 2023.

- ^ "Coeur d'Alene, Idaho Hardiness Zone Map". PlantMaps. Retrieved August 8, 2020.

- ^ a b Mann, Randy (December 20, 2012). "Microclimates cause wide differences throughout region". The Spokesman-Review. Retrieved September 30, 2020.

- ^ "Coeur d'Alene". Western Regional Climate Center. Retrieved November 20, 2021.

- ^ Woodward, Susan L. (2012–2015). "Inland Rainforests of the Northwest". Radford University. Retrieved May 4, 2021.

- ^ "xmACIS2". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved August 9, 2023.

- ^ "Coeur d'Alene, ID". NeighborhoodScout. Retrieved September 19, 2020.

- ^ Singletary (2019), pp. 50–51

- ^ "Coeur d'Alene". Emporis. Archived from the original on May 11, 2015. Retrieved September 19, 2020.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - ^ Criscione, Wilson (January 23, 2020). "As Kootenai County grows, can it preserve what makes it attractive in the first place?". Inlander. Retrieved September 19, 2020.

- ^ Dahlgren et al. (2009), pp. 122–123

- ^ Dahlgren et al. (2009), p. 116

- ^ United States Census Bureau. "Census of Population and Housing". Retrieved February 15, 2014.

- ^ "Metropolitan and Micropolitan Statistical Areas Totals: 2010–2020". 2020 Population Estimates. United States Census Bureau, Population Division. June 23, 2021. Retrieved June 23, 2021.

- ^ "Census Reporter: Spokane-Spokane Valley-Coeur d'Alene, WA-ID CSA". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved June 9, 2019.

- ^ a b McLean, Mike (December 19, 2013). "Spokane metropolitan statistical area breaks into top 100 nationwide". Spokane Journal of Business. Retrieved September 19, 2020.

- ^ "Kootenai County (Idaho)". Metro-Area Membership Report. The Association of Religion Data Archives, Pennsylvania State University. 2010. Retrieved July 28, 2020.

- ^ "101 Fastest-Growing U.S. Churches(#13)" (PDF). 2007 Outreach Magazine Report. October 8, 2007. Archived from the original (PDF) on September 20, 2008. Retrieved March 10, 2008.

- ^ Nellis, Natasha (April 9, 2020). "North Idaho looks to accommodate influx of retirees". Spokane Journal of Business. Retrieved August 8, 2020.

- ^ "Crime Comparison (NIBRS)". Kootenai County, ID. November 15, 2019. Retrieved September 19, 2020.

- ^ "Property Crime Comparison (UCR SRS Data)". Kootenai County, ID. November 14, 2019. Retrieved September 19, 2020.

- ^ "Violent Crime Comparison (UCR SRS Data)". Kootenai County, ID. November 14, 2019. Retrieved September 19, 2020.

- ^ "Crime Rates: Coeur d'Alene, ID Crime Analytics". NeighborhoodScout. Retrieved September 19, 2020.

- ^ Higgs, Robert (June 2, 2004). "Coasian Contracts in the Coeur d'Alene Mining District". Working Paper #52. Independent Institute. Archived from the original on June 15, 2010. Retrieved March 6, 2009.

- ^ Peterson, Lucas (September 13, 2017). "An Outdoor Wonderland Around the Washington-Idaho Border". The New York Times. Retrieved September 19, 2020.

- ^ Kramer, Becky (May 3, 2006). "Resort a gamble that's still paying off". The Spokesman-Review. Retrieved July 24, 2020.

- ^ "WorldMark Arrow Point #6366". RCI, LLC. Retrieved July 24, 2020.

- ^ Podplesky, Azaria (May 2, 2018). "Silverwood celebrates 30th anniversary with new additions, $19.88 tickets". The Spokesman-Review. Retrieved July 24, 2020.

- ^ Whitley, Amy (December 6, 2016). "Idaho Panhandle: Three Days, Three Ski Resorts". OutdoorsNW. Retrieved January 2, 2021.

- ^ "Idaho Economic Outlook: Coeur d'Alene Tourism Boosts all of Idaho". Idaho Politics Weekly. July 19, 2015. Archived from the original on May 6, 2017. Retrieved July 24, 2020.

- ^ Singletary (2019), p. 180

- ^ "Riverstone". City of Coeur d'Alene. Retrieved August 9, 2020.

- ^ "Hecla Mining Company". Reuters. Retrieved July 24, 2020.

- ^ "The Pita Pit". Dun & Bradstreet. Retrieved July 24, 2020.

- ^ Cole, David (April 23, 2009). "Buck Knives brings work back to U.S." Spokane Journal of Business. Retrieved July 24, 2020.

- ^ "Rocky Mountain Construction Group, Inc". Dun & Bradstreet. Retrieved January 2, 2021.

- ^ "GDP & Personal Income". United States Department of Commerce: Bureau of Economic Analysis. Archived from the original on August 14, 2018. Retrieved January 21, 2019.

- ^ "Economy at a Glance". Bureau of Labor Statistics. Retrieved September 19, 2020.

- ^ a b "QuickFacts". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved September 19, 2020.

- ^ Fisher, Sharon (June 27, 2019). "Like the rest of Idaho, Coeur d'Alene struggles with growth". Idaho Business Review. Retrieved September 19, 2020.

- ^ Saunders, Emilie Ritter (January 2, 2013). "As Idaho's Neighboring States Increase Minimum Wage, More Workers Could Seek Jobs Out Of State". StateImpact Idaho. NPR. Retrieved October 25, 2020.

- ^ "Art Galleries". Coeur d'Alene Convention & Visitor Bureau, Inc. Retrieved October 23, 2020.

- ^ Scott, Chey (November 28, 2018). "Artistic Destiny: Coeur d'Alene's Art Spirit Gallery's director navigates a changing arts landscape". Inlander. Retrieved September 19, 2020.

- ^ "Arts Commission". City of Coeur d'Alene. Retrieved October 23, 2020.

- ^ "Arts Commission: Frequently Asked Questions". City of Coeur d'Alene. Retrieved October 23, 2020.

- ^ Scozzaro, Carrie (September 19, 2019). "New faces and community outreach help raise the profile of the 40-year-old Coeur d'Alene Symphony". Inlander. Retrieved October 23, 2020.

- ^ "Theatre". Coeur d'Alene Convention & Visitor Bureau, Inc. Retrieved October 23, 2020.

- ^ "Schuler Performing Arts Center". Inlander. Retrieved October 23, 2020.

- ^ "Kroc Center". Inlander. Retrieved November 8, 2020.

- ^ Singletary (2019), p. 153

- ^ "Permanent Exhibits". Museum of North Idaho. Retrieved August 9, 2020.

- ^ "Museum of North Idaho". Smithsonian. Retrieved August 9, 2020.

- ^ "Fort Sherman Chapel". Museum of North Idaho. Retrieved August 9, 2020.

- ^ Podplesky, Azaria (June 28, 2019). "Bursting with fun: Fourth of July celebrations across the Inland Northwest". The Spokesman-Review. Retrieved August 8, 2020.

- ^ Orcutt, April (November 22, 2019). "Where to see the best holiday lights in the West". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved August 9, 2020.

- ^ "Heading to the Coeur d'Alene Holiday Light Show? Better dress in layers!". KHQ. November 29, 2019. Retrieved August 9, 2020.

- ^ Glover, Jonathan (January 2, 2019). "Hundreds ring in New Year with icy dip in Lake Coeur d'Alene for Polar Bear Plunge". The Spokesman-Review. Retrieved August 9, 2020.

- ^ "Art on the Green 2019". The Spokesman-Review. August 2, 2019. Retrieved September 28, 2020.

- ^ a b Northrup, Craig (July 3, 2020). "Downtown Association cancels Street Fair". Coeur d'Alene Press. Retrieved September 19, 2020.

- ^ Gavrich, Tim (July 8, 2019). "Trip dispatch: Contrasting courses coax golfers to Coeur d'Alene". Golf Advisor. Retrieved August 9, 2020.

- ^ "Coeur d'Alene Golf Guide". GolfTrips.com. Retrieved August 9, 2020.

- ^ "Coeur D Alene, Idaho Golf Courses". GolfLink. Retrieved August 9, 2020.

- ^ "Readers' Choice Rankings: The Top 50 Resort Courses". Golf Digest. September 17, 2009. Retrieved August 9, 2020.

- ^ Flemma, Jay (May 23, 2018). "The Floating Green at Coeur D'Alene – Still a Wonder of the Golf World". The Golf Course Trades. Retrieved August 9, 2020.

- ^ Olito, Frank (October 22, 2019). "The most famous hotel in every state". Insider Inc. Retrieved September 19, 2020.

- ^ Shepherd, Dan (August 25, 2009). "Golf Digest Magazine Ranks Circling Raven No. 17 Nationwide Among its 'America's 100 Greatest Public Courses Re-Ranked by Price'". The Golf Wire. Retrieved August 8, 2020.

- ^ "Gozzer Ranch Golf & Lake Club". Golf Digest. January 3, 2019. Retrieved August 8, 2020.

- ^ "Gozzer Ranch Golf & Lake Club". Top100GolfCourses. Retrieved August 8, 2020.

- ^ Collingwood, Ryan (November 21, 2019). "Full Ironman race announces return to Coeur d'Alene in 2021". The Spokesman-Review. Retrieved August 9, 2020.

- ^ Gary (November 22, 2019). "Return of full distance IRONMAN to Coeur d'Alene in 2021". EnduranceBusiness.com. Retrieved August 9, 2020.

- ^ Landers, Rich (July 11, 2017). "2017 Northwest Bicycling Events Calendar". The Spokesman-Review. Retrieved August 9, 2020.

- ^ Hales, Susan (July 15, 2017). "The Coeur d'Alene Crossing (August 13)". Out There Monthly. Retrieved August 9, 2020.

- ^ Hill, Kip (August 20, 2020). "Not breaking stride: CdA, Windermere marathons to take place with distancing measures". The Spokesman-Review. Retrieved September 19, 2020.

- ^ "CDA Lumbermen AA 2021 Baseball Team". The American Legion. Retrieved June 13, 2021.

- ^ Nichols, Dave (January 10, 2020). "Fight for the Fish: Lake City sweeps Coeur d'Alene in North Idaho rivalry games". The Spokesman-Review. Retrieved September 27, 2020.

- ^ "Tubbs Hill". City of Coeur d'Alene. Retrieved August 9, 2020.