The Cleveland Division of Police (CDP) is the governmental agency responsible for law enforcement in the city of Cleveland, Ohio.

| Cleveland Division of Police | |

|---|---|

Shoulder sleeve patch for patrol officers | |

Logo seen on patrol cars and documents | |

CDP badge - features number (for patrol officers) or rank in the middle. Pictured here is a detective's badge | |

| Abbreviation | CDP |

| Motto | To protect and serve |

| Agency overview | |

| Formed | 1868 |

| Jurisdictional structure | |

| Operations jurisdiction | Cleveland, Ohio, US |

| |

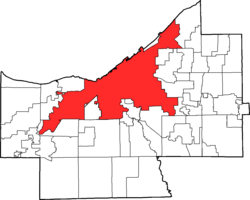

| Jurisdiction of the Cleveland Division of Police | |

| Size | 82.47 sq mi (213.6 km²) |

| Population | 372,624 (2020)[1] |

| Legal jurisdiction | City of Cleveland |

| Governing body | Cleveland City Council |

| General nature | |

| Operational structure | |

| Headquarters | 1300 Ontario Street Cleveland, Ohio, U.S. |

| Officers | 1,153 (2024) |

| Mayor of Cleveland responsible | |

| Agency executives |

|

| Parent agency | Cleveland Department of Public Safety |

| Operations | 4

|

| Facilities | |

| Districts | 5

|

| Website | |

| Division of Police | |

Under mayor Justin Bibb, Dornat "Wayne" Drummond is the current Interim Director of Public Safety, and Dorothy Todd is Chief of Police.[3]

In 2014, the Justice Department concluded an investigation into the CDP which found that the CDP had demonstrated a "pattern ... of unreasonable and unnecessary use of force" and used "guns, Tasers, 'impact weapons', pepper spray and fists in excess, unnecessarily or in retaliation" and that officers "carelessly fire their weapons, placing themselves, subjects, and bystanders at unwarranted risk of serious injury or death."[4][5] The CDP is currently operating under a consent decree to address these systemic issues.[6]

History

editBeginnings

editPrior to 1850, the preservation of the peace was left to an elected city marshal who was assisted by a number of constables and night watchmen.[7] Concerns over the adequacy of this arrangement had led, in 1837, to the formation of the Cleveland Grays, a private military company, for the partial stated purpose of assisting local law enforcement when and if the need arose.[8] In 1850, city council formally appointed the first night watch.[9] In 1866, under enabling legislation passed by the Ohio General Assembly called the Metropolitan Police Act, the Cleveland Police Department was formed, headed by a board of police commissioners tasked with the job of appointing a superintendent of police as well as a number of patrol officers.[7]

The department's early years were not without challenge and it underwent two reorganizations prior to 1893. By the end of the century, however, the climate had begun to calm and the city saw improvements in service. The department had begun to innovate by adopting a callbox system, beginning the use of police wagons, and forming a mounted unit. In 1903, the department took on its current form when the General Assembly repealed the Metropolitan Police Act and the responsibility for the formation and control of the department was given to the city.[7]

A famous painting called the passing policemen that was one hanging up at Cleveland City Hall. It was painted in the early day of the creation of the department. It portrays a policeman and a young child walking down a street talking.[10]

Pre-World War II

editFrom the early 1900s to the start of World War II, the department concentrated on managing the city's rapid growth. Cleveland was rapidly growing, even through the Great Depression, with the population increasing from 380,000 in 1900, to more than 830,000 by the 1920s.[11] The police department grew with the city, growing from less than 400 officers in 1900, to more than 1,300 by 1920. When legendary Prohibition-era crimefighter Eliot Ness became director of public safety in 1935, he abolished the existing system of precincts and reorganized the city into police districts, with each commanded by a captain.[11] Ness's system is still in use today. Under Ness, the Division of Police has experimented with new technologies and procedures, gaining a reputation as one of the most progressive and efficient departments in the nation.[11]

Post-World War II

editWhile the population of the city remained stable through the 1940s and 1950s, the police department continued to grow, with more than 2,000 officers by 1960. However, the 1960s saw relations between the department and the city's growing Black community begin to deteriorate. In 1966, even though Cleveland was over a third Black, only 165 of Cleveland's 2,200 police officers were Black, adding to the distrust between the Black community and the Division of Police[12] especially in events leading up to the Hough Riots and Glenville Shootout.

By the 1970s, the department, like the rest of the city government, was suffering from Cleveland's failing economy. Aging equipment could not be replaced, and the department saw its numbers drop by more than 700 by the end of the decade. This, along with rising crime rates left the police department with a reputation as a disorganized and demoralized force that would take decades to lose.[11] Further aggravating the situation, The City of Cleveland was found guilty of discriminating against minorities in hiring, promoting, and recruiting government officials, specifically police officers, by a federal court in 1977.[11] As a result of this judgement, the department was forced to place an emphasis on rebuilding community relations and recruiting minorities. By 1992, the number of police officers increased by more than 300 officers to 1,700, of whom 26% were black. During the administration of Michael White the department began to focus on community policing and rebuilding the damaged relationship between the department and the community. Nonetheless, during the White administration the role of police chief was "a revolving door of chiefs".[11]

Under the Jane L. Campbell administration of 2002–06, the Division of Police laid off more than 200 officers. The Police Aviation Unit was grounded. Ports and Harbor was disbanded, even the CDP Mounted (Horse) unit was disestablished. The department was again seen as a demoralized force during the Campbell administration.[11]

Under mayor Frank Jackson, nine previously laid-off patrol officers were reinstated and a new class of police officers has graduated from the academy. Mayor Jackson has reduced the number of Police Districts from six to five and has ordered police to be aggressive in the fight against crime. The CDP mounted unit has been restored and those mounted officers patrol the downtown area. Mayor Jackson has had only one chief of police: Michael McGrath,[13] as head of administration, as opposed to other administrations. The Cleveland Police are also investigating the possibility of remodeling certain aspects of the department after the NYPD, including initializing a CompStat system.

Under Mayor Jackson, the department has also embarked upon a program of increased cooperation and coordination with other law enforcement agencies in the region. Since 2011, the Division has employed a LEVA (Law Enforcement and Emergency Services Video Association) Certified Specialist to capture, examine, compare and evaluate all recorded audio/video evidence that can be associated with crimes within the city. This has yielded convictions in cases from simple burglary up to and including high-profile homicide cases. It is part of the city's commitment to leveraging technology to create a safer city. Cleveland Police have recently formed a financial crimes unit. Mayor Jackson has restored the Cleveland Police Aviation Unit and there have been talks about turning control of the unit over to the Cuyahoga County Sheriff's Department so as to allow the unit to provide aerial services to the suburbs as well as the central city.[14] A reorganized marine patrol was unveiled in 2010 in partnership with the sheriff and the Lakewood and Euclid city departments.[14] Changes to the command structure have included the assignment of a department commander to supervise the department's intelligence and crime analysis operations as well as coordinate the department's efforts with those of the Northeast Ohio Regional Fusion Center.[14]

In 2017, Cleveland Police became the final group of the city's first responders to carry the naloxone nasal spray Narcan, the opioid antagonist that can reverse the effects of a drug overdose. 150 zone cars were initially equipped with the drug, with roll-out to the remaining fleet to follow. More than 900 officers were in the first group to receive Narcan administration training, with the focus on patrol officers who answer 911 calls. Some detectives were also trained. The kits that police use contain twice the dosage of those used by firefighters and EMS technicians, as police may have to dispense several doses of the drug to counteract an overdose. The division typically is faced with several overdoses per day. Overall, Cuyahoga County suffered 228 opioid overdose deaths in 2015, 666 in 2016, and 775 in 2017.[15]

In 2021, the Safer Cleveland Ballot Initiative passed, creating the Cleveland Community Police Commission composed of 13 civilians with final decision-making power regarding discipline in police misconduct cases.[16]

Notable cases involving the CDP

edit- 1908 – Collinwood school fire.

- 1935 – Torso Murders, in Cleveland. CDP found the torsos and decapitated bodies in Cleveland's, Kinsman, Slavic Village and Flats areas.

- 1954 – Cleveland Police assisted Bay Village, Ohio Police with the Sam Sheppard case.

- 1963 – Terry v. Ohio (case decided 1968) – U.S. Supreme Court case establishing Constitutionality of police stop-and-frisk procedures

- 1971 – Cleveland Police arrested actress/activist Jane Fonda at Cleveland Hopkins Airport.

- 1977 – Murder of mob boss Danny Greene

- 1985 – Cleveland Police SWAT Team assaults a hijacked – Pan American World Airways airliner and subdues the hostage taker. No lives lost.

- 2003 – Case Western Reserve University shooting

- 2007 – Shooting at Cleveland SuccessTech Academy. Shooter is the only fatality.

- 2009 – Cleveland Strangler Case; 11 dead bodies were found and 6 have been identified as of November 2009.

- 2012 – Five dozen police cruisers involved in a 23-minute chase resulting in 137 shots fired and the killing of two unarmed people. Sixty-three suspensions handed down in October 2013.[17][18][19]

- 2002–2013 – Three Cleveland women were kidnapped and held in a man's house for almost 10 years before CDP officers responded to 9-1-1 calls to the house.

- 2014 – Two CDP officers were involved in the fatal shooting of Tamir Rice.

Fallen officers

editSince 1853, the Cleveland Division of Police has lost 108 officers in the line of duty. Seventy-five of them were gunfire-related. All the Cleveland Division of Police members line of duty deaths have been male.[20][21]

Controversy

editFrom 2014 onwards, the city of Cleveland has spent at least $1 million annually in settlements related to police misconduct. In 2017, it spent nearly $8 million.[22]

Hough riots

editThe Hough riots were race riots in the predominantly African American community centered on Hough Avenue that took place over a six-night period from July 18 to July 23, 1966, after a series of racially motivated confrontations outside of a neighborhood bar.[23] Racial tension was high between Cleveland's police and its African American community to begin with, and played a crucial role in further escalating the situation. Once it was determined that the CDP was unable to handle the situation without assistance, then-Mayor Ralph Locher asked Ohio Governor James A. Rhodes for state assistance and, on July 20, the Ohio National Guard entered the Hough neighborhood to help restore order.[23][24] During the riots, three Cleveland Police Officers were killed, four African Americans were killed, 30 people were critically injured, there were 275 arrests, and more than 240 fires were reported.[23]

Glenville shootout

editThe Glenville shootout was the culmination of a series of violent incidents that occurred in the Glenville section of Cleveland from July 23 to July 28, 1968.[25] The main incident began on the evening of July 23, 1968 in the eastern section of the Glenville neighborhood. Cleveland police officers were watching Fred Ahmed Evans and his radical militant group, who were suspected of purchasing illegal weapons.[25] It was not clear who shot first, but Evans and the police exchanged gunfire. The shootout attracted a large crowd that was described as "mostly black, young, and 'hostile'".[25] The following day, when it became clear that the department was ill-equipped to handle the situation, then-mayor Carl B. Stokes asked Governor James A. Rhodes to activate and deploy elements of the Ohio National Guard. The violent events of the first night resulted in the deaths of seven people, and injuries of fifteen others.[25]

Hongisto feud

editAs then-mayor-elect, Dennis Kucinich appointed former San Francisco Sheriff Richard D. Hongisto as chief of police in 1977, a decision he would later come to regret.[26] Hongisto became immensely popular in Cleveland, especially with the city's ethnic Eastern European community. The chief was also popular with the media, especially after Hongisto saved a person from a snow bank during a 1978 snowstorm.[27] However, on March 23, Kucinich publicly suspended Hongisto for refusing to accept civilian control. Hongisto asserted that Kucinich interfered with the operation of the division.[28] Specifically, he stated that Kucinich's executive secretary Bob Weissman had pressured him to "punish" Kucinich opponents on the City Council and to reward police jobs to Kucinich supporters with "questionable ethics." In turn, Kucinich charged Hongisto with insubordination.[28]

In a press conference televised on Good Friday 1978, Kucinich gave Hongisto a 24-hour deadline to support his assertions. Then the mayor fired the chief on live local television.[28] The controversial firing would be one of the underlying causes of Kucinich's near-removal from office.[29]

Chief William Hanton and Lt. Howard Rudolph's drug dealing cops

editA special unit of Cleveland narcotics officers known as "The A Team" became partners with two drug dealers named Arthur Feckner and Leonard Brooks in 1985 to raise more than $560,000 for an undercover sting that led them to Miami, Florida. Chief of Police William Hanton and his "heir', Lt. Howard Rudolph, protected Feckner and Brooks while they sold more than $500,000 in crack to poor Cuyahoga Metropolitan Housing Authority (CMHA) residents living at and around Woodhill Estates. The housing estate and surrounding neighborhood was nearly 99 percent African American. George Voinovich was the city's mayor and attorney George Forbes was council president.

According to an investigative news story published in the LA Times, and written by Eric Harrison on June 14, 1989, Feckner and Brooks were generating about $60,000 a day and delivering the cash to "A Team" cop Lynn Bistricky who then turned it over to Hanton. This went on 7 days a week from mid-June to late July 1985 for about 45 days according to Harrison's LA Times story.[30] The A Team working with the DEA made the bust in Miami and it would have been successful until news of how the money was raised for the buy became public and the NAACP got involved. U.S. Rep. Louis Stokes called for a federal investigation in 1987. By then, Hanton had retired and Rudolph was chief.[30]

Cleveland's Black community, once again betrayed by the city's police, were outraged that cops were behind a $60,000 a day crack operation that ruined more lives.

Cuyahoga County Prosecutor John T. Corrigan got a grand jury indictment against five of the police officers who partnered with Feckner and Brooks, but the case was assigned to his pro-police son, Michael Corrigan, as a judge. Judge Michael Corrigan ruled in a bench and not a jury trial that the drug dealing police had committed no crimes.[30]

High-speed chase

editOn November 29, 2012, 104 Cleveland police officers were involved in a high-speed chase that resulted in the shooting and killing of a man and a woman. Officer Michael Brelo was charged with two counts of voluntary manslaughter and was acquitted of the charges on May 23, 2015.

On October 16, 2013, Police Chief Michael McGrath announced suspensions totaling 178 days for sixty-three of the officers who joined the chase in violation of department regulations. None of the thirteen officers who fired any of the 137 shots at the unarmed couple were part of this group of officers. They were subject of a criminal investigation being conducted by Cuyahoga County Prosecutor Timothy McGinty.[31]

Tamir Rice

editOn November 22, 2014, Tamir Rice, a 12-year old African-American boy, was shot at Cudell Recreation Center by a Cleveland Police officer responding to a report of someone pointing a gun ("possibly fake" according to the 911 caller – a statement not relayed to the responding officers) at people. While the officer claimed that he had warned Rice to put down the gun, surveillance video showed Rice being shot as he reached into his waistband pulling the "gun" out. This occurred within seconds of the police cars' arrival on the scene.[32]

In the aftermath of the shooting, it was reported that Timothy Loehmann, who was identified as the officer having fired the shots that killed Rice, had been deemed an emotionally unstable recruit, and unfit for duty in his previous job as a policeman in Independence, Ohio.[33][34]

Opposition to civilian oversight

editThe union for CDP officers has advocated against creating a civilian oversight panel with the authority to fire problem CDP officers.[35]

Justice Department investigation

editIn December 2012, after a series of deadly force incidents, Cleveland mayor Frank G. Jackson, local U.S. Representative Marcia Fudge, and others asked the United States Department of Justice to investigate the division.[36] The Justice Department announced the beginning of its probe on March 14, 2013.[37] On December 4, 2014, United States Attorney General Eric Holder announced the completion of an investigation into a long-term pattern of excessive force by Cleveland Division of Police officers.[38][39]

The Justice Department report was released on December 4, 2014.[40] The report found that from 2010 to 2013, the Cleveland police had demonstrated a "pattern ... of unreasonable and unnecessary use of force" and used guns, Tasers, "impact weapons", pepper spray and fists in excess, unnecessarily or in retaliation. The report further found officers also use excessive force on those "who are mentally ill or in crisis."[41] The report also highlights that officers "carelessly fire their weapons, placing themselves, subjects, and bystanders at unwarranted risk of serious injury or death", and noted that "many African-Americans reported that they believe [Cleveland police] officers are verbally and physically aggressive toward them because of their race."[42]

Consent decree with Department of Justice

editThe agreement follows a two-year Department of Justice investigation, prompted by a request from Cleveland Mayor Frank Jackson,[43] to determine whether the CDP engaged in a pattern or practice of the use of excessive force in violation of the Fourth Amendment of the United States Constitution and the Violent Crime Control and Law Enforcement Act of 1994, 42 U.S.C § 14141. Under Section 14141, the Department of Justice is granted authority to seek declaratory or equitable relief to remedy a pattern or practice of conduct by law enforcement officers that deprives individuals of rights, privileges, or immunities secured by the Constitution or federal law.

U.S. Attorney General Eric Holder and U.S. Attorney Steven Dettelbach announced the findings of the DOJ investigation in Cleveland on December 4, 2014.[4] After reviewing nearly 600 use-of-force incidents from 2010 to 2013 and conducting thousands of interviews, the investigators found systemic patterns insufficient accountability mechanisms, inadequate training, ineffective policies, and inadequate community engagement.[4][5]

At the same time as the announcement of the investigation findings, the City of Cleveland and the Department of Justice issued a Joint Statement of Principles agreeing to begin negotiations with the intention of reaching a court-enforceable settlement agreement.

The details of the settlement agreement, or consent decree, were released on May 26, 2015. The agreement mandates sweeping changes in training for recruits and seasoned officers, developing programs to identify and support troubled officers, updating technology and data management practices, and an independent monitor to ensure that the goals of the decree are met. The agreement is not an admission or evidence of liability, nor is it an admission by the city, CDP, or its officers and employees that they have engaged in unconstitutional, illegal, or otherwise improper activities or conduct. Pending approval from a federal judge,[44] the consent decree will be implemented and the agreement is binding.

Provisions of the consent decree

editThe Cleveland Consent Decree is divided into 15 divisions, with 462 enumerated items.[6] At least some of the provisions have been identified as unique to Cleveland:

- a civilian inspector general who will review the work of the police officers. This position will be appointed by the mayor but report to the Police Chief. It is intended to provide an additional layer of accountability and scrutiny.[45]

- an equipment inventory that must result in a study by the police that shows what is needed.[46]

On June 12, 2015, Chief U.S. District Judge Solomon Oliver Jr. approved and signed the consent decree.[47] The signing of the agreement starts the clock for numerous deadlines that must be met. These deadlines include:

- Within 90 days (September 10, 2015):

- The City of Cleveland and the USDOJ must appoint a monitor. The monitor, in turn, within 120 days of appointment, must develop a plan to conduct compliance reviews of the police department. The monitor's term lasts a minimum of five years.[48]

- The 130-member Community Police Commission must be established. The commission will make recommendations on community-oriented, bias-free and transparent policing. Once established, they must hold meetings throughout the city.[48]

- CDP must designate a crisis intervention coordinator to foster better communication between the police department and the mental-health community.[48]

- Within 120 days (October 10, 2015): Cleveland Mayor Frank Jackson[48] and the Cleveland City Council will have to place a charter amendment on the ballot that ensures a transparent process for appointment of police review board members.[48]

- Within 150 days (November 9, 2015): A system for tracking complaints must be established by the Cleveland Office of Professional Standards. The office will have 90 days to develop criteria for both standard and complex complaints.[48]

- Within 180 days (December 9, 2015):

- The federal monitor must survey Cleveland communities to determine how their perceptions of police have changed. The survey will be conducted every two years, with public reports being filed every six months on how well the police department is following the consent decree's requirements.[48]

- CDP must put together a mental health advisory committee. This committee will help officers develop better strategies for responding to incidents involving mental-health issues.[48]

- The Office of Professional Standards will develop a revised operations manual and make it available to the public.[48]

- CDP must develop a training curriculum in accordance with the consent decree.[48]

- CDP must start using a department-wide email system to improve communication. Patrol officers will not have access to information about misconduct allegations.[48]

- Within 270 days (March 8, 2016): The police department must revise its field-training manual to put it in line with the consent decree. It must also develop a mechanism for recruits that allows them to provide feedback about the effectiveness of their training.[48]

- Within 365 days (June 12, 2016):

- CDP will have the systems in place to monitor police outreach to the community. The federal monitor will assess how well they work.[48]

- CDP will provide current officers with training in use-of-force decision-making, use-of-force reporting requirements, the Fourth Amendment, and deescalation of conflict techniques.[48]

- CDP will implement a uniform use-of-force reporting system.[48]

- CDP will ensure that all officers have gone through at least eight hours of crisis intervention training,[48]

- The Office of Professional Standards must train investigators on how to conduct in-depth administrative investigations.[48]

- The City of Cleveland must provide the public with information on how to file complaints through the Office of Professional Standards. The City must also train police personnel on how to take civilian complaints.[48]

- CDP's Training Review Committee must develop a written training plan for recruitment and training. The plan must ensure police officers are effectively trained in accordance with the consent decree's guidelines.[48]

- CDP must assess equipment needs relative to satisfying the consent decree.[48]

- CDP must complete a study to determine how many sworn officers and civilian personnel it needs to fulfill its responsibilities and comply with the decree. Within 180 days of completion of the study, CDP must develop a staffing plan.[48]

- CDP must implement mandatory training for all supervisors as aligned with the consent decree.[48]

- CDP must create a plan to modify the officer intervention program to better manage and identify problem police officers.[48]

- Within 18 months (December 12, 2016): CPD must develop a bias-free policing policy based on the Community Police Commission's recommendations. The policy will be used in hiring decisions and promotion of police officer decisions.[48]

- Within two and a half years (December 12, 2017): The monitor will complete an assessment and determine compliance with and impact of the consent decree guidelines.[48]

- At five years (June 12, 2020): If CPD has not demonstrated compliance with the consent decree, the monitor's term will be extended. However, only upon a court's determination can the monitor's oversight be extended beyond seven years.[48]

Organization

editAdministrative operations

editProvides services that enable the other programs to effectively respond to service calls. It provides security services; warrant, subpoena and property processing; radio and telephone communications; inspection of police services; and management of information and human resources. Additional functions include the reporting and recording of crimes and incidents and personnel development.

Field operations

edit- Bureau of Traffic

- As part of Field Operations, the Bureau of Traffic provides traffic and crowd control at major events

- Motorcycle unit

- Accident Investigation Unit

- Mounted Unit

- Downtown Services Unit (D.S.U)

- In May 2008 the D.S.U. was created to offset the closing of the old Third District while still providing a police presence in the downtown area. In addition to regular patrol the D.S.U. is involved in policing special events, the Warehouse District, as well as numerous undercover enforcement operations.

- D.A.R.E. programs

- Community Relations

- Auxiliary Police

- Parapolice

- Litter Unit

- City Hall Security

- Metro SRO

- Bike Patrol

- Public Welfare

- Public utilities police

- Aud and Stadium police

- Canine Unit (K9)

- Patrol

- Airport Police

- Highly trained officers who are permanently assigned to serve Cleveland Hopkins International Airport. They provide a comprehensive set of law enforcement services including routine patrol, crime investigation, vehicle traffic management, and control-and-response to airport emergencies.[49]

- District Support

- District support sections assist uniformed patrols through the investigation of major offenses, concentrated action on specific complaints, and crime pattern analysis.

Special operations

edit- S.W.A.T (founded in 1979)

- Impact Task Force (founded in 1962 disestablished shortly after renamed S.W.A.T)

- Tactical Unit (founded in 1963 disestablished shortly after)

- Aviation Unit (Founded in 1990)

- Does patrols for the city, mostly at night. The unit flies MD Helicopters MD 500 model MD 560E-369E. The helicopters carry very expensive equipment, including a two hundred thousand dollar Thermographic camera. The unit is looking into changing from the Cleveland Division of Police-Aviation Unit to the Cuyahoga County Sheriff's Aviation Unit. This way they can patrol a greater area.

- Ports, Harbor Unit and Dive team (Founded 1939)

- Mounted Unit

- Investigations Division

- Detective Bureaus

- Arson

- Auto Theft

- Fraud

- Narcotics

- Robbery/Homicide

- Sex Crimes/Special Victims (Vice Unit)

- Youth Domestic Violence

- Detective Bureaus

- Technical Support Division

- Photography Lab Services

- Forensics and Crime Scene Investigation/Analysis

- Accident Investigation Unit

- Medical Unit

- Gang Units (for city and school districts)

- Bomb Squad

Police Oversight & Accountability

editSource:[50]

- The Monitoring Team

- Police Accountability Team

- Office of the Inspector General

- Internal Affairs

- Office of Professional Standards

- Civilian Police Review Board

- Community Police Commission

Clubs and societies within the department

edit- Cleveland Police Emerald Society

- Polish American Police

- Cleveland Police Patrolmen's Association (CPPA) – the union for the department's officers

- Pipes and Drums

Rank structure and insignia

edit| Title | Insignia |

|---|---|

| Chief | |

| Deputy Chief | |

| Commander | |

| Captain | |

| Lieutenant | |

| Sergeant | |

| Patrol Officer/Detective/Field Training Officer |

Demographics

edit- Male: 83%

- Female: 17%

- White: 64%

- African-American/Black: 36%

- Other: 6%[51]

Resources

editThis section needs to be updated. (November 2024) |

Cleveland has primarily relied on black and white Ford Crown Victoria Police Interceptors for the past 25 years although there are a number of pre-2008 black and white Ford Taurus cars in the fleet. However, Cleveland's continued reliance on the Crown Victoria will not be possible given Ford's discontinuation of the Crown Victoria program in 2011. The Chevrolet Impala and the Dodge Charger were being viewed as possible replacements. In 2012, The Cleveland Division of Police selected the Charger for its future squad car. They also have bought the new police interceptor and police interceptor utility. They also use the Chevy Tahoe at Hopkins airport and downtown. The new colors scheme for Cleveland police vehicles are black and blue.

In 2014, the Cleveland Division of Police stopped purchasing Chargers as their primary squad cars and switched to the Ford Taurus. The Division cited that the Dodge Chargers frequently broke down and did not handle big city streets well. The primary reason for the switch however was that the Dodge Charger has a very low ground clearance compared to the Ford Crown Victoria and Ford Taurus, which led to many squad cars suffering severe undercarriage damage when Cleveland Officers attempted to drive over curbs or through fields while responding to certain incidents or calls.[52]

CPD officers are issued either Glock 17 or Glock 19 9mm sidearms. The 9mm Glocks replaced the older .40 S&W Glock Model 22 and Model 23 which were in usage. The Cleveland Police issued Glock Model 22 .40 had "CLVLNDOHPD" which was short for Cleveland Ohio Police Department and the pistols before the Glocks had the same agency markings which were issued through the 1990s until around 2003 which were the Smith & Wesson 5943, which is a variant of the Smith & Wesson 5906. Tasers, OC pepper spray and the 21-inch ASP expandable straight baton are carried by officers as less lethal options. Handcuffs and a portable radio are also carried.

See also

editReferences

edit- ^ "U.S. Census Bureau QuickFacts: Cleveland city, Ohio". Census.gov. Archived from the original on January 3, 2022. Retrieved February 26, 2022.

- ^ "Mayor Bibb Announces Permanency of Public Safety Chief Director Dornat A. Drummond | City of Cleveland Ohio".

- ^ Sapolin, Alec (February 23, 2024). "Cleveland's Chief Public Safety Director resigns, city appoints woman police chief". Cleveland19.com. Retrieved February 23, 2024.

- ^ a b c "Justice Department wants sweeping changes in Cleveland Police Department; report finds 'systemic deficiencies'". Cleveland.com. December 2014. Archived from the original on December 11, 2014. Retrieved October 23, 2017.

- ^ a b "Forcing Change: A decade of civil rights lawsuits against Cleveland police preceded U.S. Justice Department investigation". Cleveland.com. January 2015. Archived from the original on October 24, 2017. Retrieved October 23, 2017.

- ^ a b "CLE Consent Decree". Archived from the original on December 31, 2015.

- ^ a b c "Cleveland Police Department – The Encyclopedia of Cleveland History". The Encyclopedia of Cleveland History. May 20, 2002. Archived from the original on February 10, 2012. Retrieved September 8, 2012.

- ^ Vourlojianis, George N. (2002). The Cleveland Grays: An Urban Military Company, 1837–1919. Kent, Ohio: The Kent State University Press. p. 14. ISBN 0-87338-678-7.

- ^ Kollar, Mary Ellen (March 2, 1998). "Cleveland City Government – The Encyclopedia of Cleveland History". Encyclopedia of Cleveland History. Archived from the original on April 29, 2012. Retrieved September 8, 2012.

- ^ "Paintings Conservation Donated to the Cleveland Police Museum". September 7, 2017. Archived from the original on May 8, 2019. Retrieved May 8, 2019.

- ^ a b c d e f g "Cleveland Police Department". Encyclopedia of Cleveland History | Case Western Reserve University. May 31, 2019. Archived from the original on June 20, 2019. Retrieved July 17, 2019.

- ^ "Hough Riots". Archived from the original on October 6, 2007. Retrieved July 3, 2008., Ohio History Central

- ^ "City of Cleveland". www.city.Cleveland.oh.us. Archived from the original on October 24, 2017. Retrieved October 23, 2017.

- ^ a b c Gillispie, Mark (January 3, 2011). "Cleveland Police Department announces reorganization aimed at threats posed by gunmen, explosive devices". Cleveland.com. The Plain Dealer. Archived from the original on May 19, 2012. Retrieved November 13, 2012.

- ^ Astofoli, Courtney (January 11, 2019). "Cleveland police officers begin carrying overdose reversal drug Narcan". cleveland.com. Cleveland OH: Advance Ohio. Archived from the original on August 6, 2020. Retrieved June 2, 2020.

- ^ "Yes on Issue 24, which would provide community police oversight, passes". WEWS. November 3, 2021. Archived from the original on February 10, 2022. Retrieved February 10, 2022.

- ^ "Cleveland police to discipline 75 officers for role in deadly chase". August 2013. Archived from the original on October 12, 2014. Retrieved October 8, 2014.

- ^ "Cleveland police to suspend 63 officers for roles in deadly November chase". October 15, 2013. Archived from the original on October 12, 2014. Retrieved October 8, 2014.

- ^ "63 Cleveland Police Officers Suspended Over Deadly Chase". Archived from the original on October 14, 2014. Retrieved October 8, 2014.

- ^ "The Officer Down Memorial Page". Archived from the original on September 23, 2016. Retrieved January 24, 2017.

- ^ "Home | GCPOMS". Policememorialsociety.org. Archived from the original on May 8, 2019. Retrieved February 26, 2022.

- ^ Thomson-DeVeaux, Amelia (February 22, 2021). "Police Misconduct Costs Cities Millions Every Year. But That's Where The Accountability Ends". FiveThirtyEight. Archived from the original on February 22, 2021. Retrieved February 22, 2021.

- ^ a b c Walter Johnson. "The Night They burned Old Hough". Archived from the original on May 24, 2017. Retrieved October 23, 2017.

- ^ Hough Riots Archived May 31, 2012, at the Wayback Machine, Hough Riots – Encyclopedia of Cleveland History.

- ^ a b c d The Encyclopedia Of Cleveland History by Cleveland Bicentennial Commission (Cleveland, Ohio), David D. Van Tassel (Editor), and John J. Grabowski (Editor) ISBN 0-253-33056-4

- ^ Condon, George E. (1979). Cleveland: Prodigy of the Western Reserve. Tulsa: Continental Heritage Press. pp. 169–170. ISBN 978-093298606-1.

- ^ Swanstrom, Todd (1985). The Crisis of Growth Politics: Cleveland, Kucinich, and the Challenge of Urban Populism. Philadelphia: Temple University Press. pp. 214–215. ISBN 978-0877223665.

- ^ a b c McGunagle, Fred (August 1, 1999). "Our Century: 'Boy Mayor' Leads Battle Into Default" (PDF). The Plain Dealer. Archived (PDF) from the original on June 30, 2021. Retrieved July 3, 2021.

- ^ Larkin, Brent (March 27, 1978). "Kucinich slips in Press poll". Cleveland Press. p. A1.

- ^ a b c "Cleveland Scandal : Did Cocaine Sting Fuel Drug Sales?". Los Angeles Times. June 14, 1989. Archived from the original on June 2, 2017. Retrieved April 16, 2020.

- ^ Blackwell, Brandon (October 16, 2013). "Cleveland police to suspend 63 officers for roles in deadly November chase". The Plain Dealer. cleveland.com – Northeast Ohio Media Group LLC. Archived from the original on October 12, 2014. Retrieved October 17, 2013.

- ^ McCarthy, Tom (November 26, 2014). "Tamir Rice: video shows boy, 12, shot 'seconds' after police confronted child". The Guardian. Archived from the original on November 27, 2014. Retrieved December 4, 2014.

- ^ Mai-Duc, Christine (December 4, 2014). "Cleveland officer who killed Tamir Rice had been deemed unfit for duty". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on December 4, 2014. Retrieved December 5, 2014.

- ^ "Cleveland officer who fatally shot Tamir Rice judged unfit for duty in 2012". The Guardian. December 4, 2014. Archived from the original on February 10, 2021. Retrieved December 5, 2014.

- ^ "Cleveland residents look to take police reform into their own hands". Washington Post. ISSN 0190-8286. Archived from the original on August 10, 2021. Retrieved October 25, 2021.

- ^ Atassi, Leila (December 27, 2012). "Cleveland Mayor Frank Jackson seeks outside review of all future use of deadly force cases (updated)". Northeast Ohio Media Group. The Plain Dealer. Archived from the original on December 10, 2014. Retrieved December 4, 2014.

- ^ Atassi, Leila. "Cleveland police under investigation by U.S. Justice Department (video) (photo gallery)". Northeast Ohio Media Group. The Plain Dealer. Archived from the original on December 5, 2014. Retrieved December 4, 2014.

- ^ Blackwell, Brandon (December 4, 2014). "Read the Justice Department's review of the Cleveland Division of Police". Northeast Ohio Media Group. The Plain Dealer. Archived from the original on December 10, 2014. Retrieved December 4, 2014.

- ^ McCarthy, James F. (December 4, 2014). "Justice Department wants sweeping changes in Cleveland Police Department; report finds 'systemic deficiencies'". The Plain Dealer. Archived from the original on December 11, 2014. Retrieved December 5, 2014.

- ^ "Investigation of the Cleveland Division of Police" (PDF). www.justice.gov. Archived from the original on November 11, 2020.

- ^ "Justice Dept.: Cleveland police have pattern of excessive force". CNN. December 4, 2014. Archived from the original on December 4, 2014. Retrieved December 4, 2014.

- ^ "Feds Find Shocking, Systemic Brutality, Incompetence In Cleveland Police Department". The Huffington Post. December 4, 2014. Archived from the original on December 6, 2014. Retrieved December 6, 2014.

- ^ "DOJ consent decree: How long does the Cleveland police department have to implement changes?". Cleveland.com. May 2015. Archived from the original on October 24, 2017. Retrieved October 23, 2017.

- ^ "Cleveland consent decree provides blueprint for long-elusive police reforms: The Big Story". Cleveland.com. May 2015. Archived from the original on October 24, 2017. Retrieved October 23, 2017.

- ^ "Cleveland will create Police Inspector General as part of Justice Department reform". May 27, 2015. Archived from the original on May 30, 2015. Retrieved June 6, 2015.

- ^ "Some changes outlined in consent decree unique to Cleveland, Justice Department says". May 27, 2015. Archived from the original on May 30, 2015. Retrieved June 6, 2015.

- ^ "Federal judge approves Cleveland consent decree, calls it a 'good, sound agreement'". June 12, 2015. Archived from the original on June 15, 2015. Retrieved June 13, 2015.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z "DOJ consent decree: How long does the Cleveland police department have to implement changes?". May 27, 2015. Archived from the original on October 24, 2017. Retrieved June 13, 2015.

- ^ "Security Information – CLE". Airport Guide – Security Information. City of Cleveland – Department of Port Control – Cleveland Airport System. Archived from the original on December 30, 2012. Retrieved December 25, 2012.

- ^ "Police Oversight & Accountability | City of Cleveland Ohio". www.clevelandohio.gov. Retrieved March 17, 2024.

- ^ Law Enforcement Management and Administrative Statistics, 2000: Data for Individual State and Local Agencies with 100 or More Officers Archived September 27, 2006, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Cleveland buys 65 new police cars as Justice Department continues to monitor fleet - Cleveland.com (The Plain Dealer)