Section 28 refers to a part of the Local Government Act 1988, which stated that local authorities in England, Scotland and Wales "shall not intentionally promote homosexuality or publish material with the intention of promoting homosexuality" or "promote the teaching in any maintained school of the acceptability of homosexuality as a pretended family relationship".[1] It is sometimes referred to as Clause 28,[2] or as Section 2A in reference to the relevant Scottish legislation.[3]

The legislation came into effect during Margaret Thatcher's premiership on 24 May 1988.[4] It caused many organisations, such as LGBT student support groups to either close, limit their activities or to self-censor.[5] In addition, Section 28 had a widespread impact on schools across the United Kingdom. This was due to uncertainty around what constituted the "promotion" of homosexuality, leading many teachers to avoid discussing the topic in any educational context.[6]

Section 28 was first repealed in Scotland under the Ethical Standards in Public Life etc. (Scotland) Act 2000.[7] It was subsequently repealed in England and Wales in November 2003,[8] following New Labour's initial unsuccessful attempt to repeal the legislation under the Local Government Act 2000.[9]

History

editBackground

editHomosexuality was decriminalised for men over the age of 21 under the Sexual Offences Act 1967,[10] following recommendations made in the Wolfdenden report in 1957.[11] However, discrimination against gay men, and LGBT people in general, continued in the following decades.

This was exacerbated in 1981,[12] as the first recorded cases of HIV/AIDS were found in five gay men with no previous health issues.[13] The mass media, as well as medical professionals, then associated HIV/AIDS with gay and bisexual men. Although subsequent medical research showed that gay men were not the only people who were susceptible to contracting the virus,[14] the perceived association with HIV/AIDS increased the stigmatisation of gay and bisexual men. This correlated with higher levels of discrimination towards LGBT people.[15]

Rising negative sentiments towards homosexuality peaked in 1987, the year before Section 28 was enacted. According to the British Social Attitudes Survey, 75% of the population said that homosexual activity was "always or mostly wrong", with just 11% believing it to be "not wrong at all". Five years prior to the enactment, a similar BSAS poll had found that 61% of Conservative and 67% of Labour voters believed homosexual activity to be "always or mostly wrong".[16]

The law's precursor was the publication in 1979 of LEA Arrangements for the School Curriculum, which required local authorities to publish their curriculum policies. Following the legalisation of homosexuality proposals for Scotland (added as an amendment to what became the Criminal Justice (Scotland) Act 1980 by Labour MP Robin Cook), guidance was published indicating that schools should not teach homosexuality as part of sex education lessons. This was part of a deal to ensure government support for legalisation of homosexuality in Scotland.[citation needed]

This was followed, two years later, by the School Curriculum (25 March 1981), in which the secretaries of state (for Education and Wales) said they had decided to "set out in some detail the approach to the school curriculum which they consider should now be followed in the years ahead". Every local education authority was expected to frame policies for the school curriculum consistent with the government's "recommended approach" (DES 1981a:5) which required teaching of only heterosexual intercourse in schools.[17]

Despite growing levels of homophobia in 1980s Britain, several Labour-led councils across the country introduced a range of anti-discrimination policies[18] and provided specialist support services for their LGBT constituents. The Greater London Council also granted funding to a number of LGBT organisations, including the London Lesbian and Gay Community Centre in Islington.[19] About 10 of the 32 local authorities in London, most prominently Islington and Haringey were also funding gay groups at that time, one report estimating that these boroughs and the GLC together donated more than £600,000 to gay projects and groups during 1984.[20]

The attention to this, and the alliances between LGBT and labour unions (including the National Union of Mineworkers (NUM)) – formed by activist groups such as Lesbians and Gays Support the Miners and Lesbians Against Pit Closures – led to the adoption at the Labour Party Annual Conference in 1985 of a resolution to criminalise discrimination against lesbian, gay and bisexual people. This legislation was supported by block voting from the NUM.[21] In addition, the election to Manchester City Council of Margaret Roff in November 1985 as the UK's first openly lesbian Mayor[22] and the publication of Changing The World by the GLC in 1985[23] all fuelled a heightened public awareness of LGBT rights.

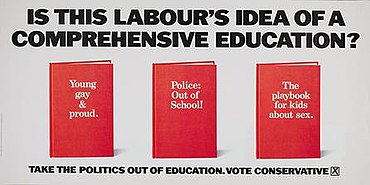

Islington London Borough Council received further attention in 1986, when the Islington Gazette reported that a copy of the children's book Jenny Lives with Eric and Martin was available in a local school library. The copy found by the Islington Gazette was actually located in an Inner London Education Authority teachers’ resource centre, and there was no evidence to support the newspaper's claim that it was seen or used by children. However, the book's portrayal of a young girl living with her father and his male partner provoked widespread outrage from the right-wing press and Conservative politicians.[24] Following this, the 1987 election campaign saw the Conservative Party issue posters attacking the Labour Party for supporting the provision of LGBT education. Jenny Lives with Eric and Martin was referenced frequently in the parliamentary debates that led to the introduction of Section 28.[25]

Legislation

editPrior to the introduction of Section 28, Conservative politicians became concerned about the future of the nuclear family[26] as fewer people were getting married and divorce rates were increasing.[18] In an attempt to mitigate these fears, the government introduced a clause to the Education (No. 2) Act 1986 which stated that sex education should “encourage … pupils to have due regard to moral considerations and the value of family life”.[27] However, some Conservatives also blamed the perceived decline of the nuclear family on members of the LGBT community.[28] During this time, Conservative backbench MPs such as Jill Knight also believed that schools and Labour-run local authority areas would provide materials that would ‘promote homosexuality’ to children.[9]

Consequently, in 1986, Lord Halsbury first tabled the Local Government Act 1986 (Amendment) Bill,[29] whose long title was An act to refrain local authorities from promoting homosexuality, in the House of Lords. The bill became commonly known as the Earl of Halsbury's Bill. Although it successfully passed both the House of Lords and the first stage in the House of Commons, further attempts to pass the bill were impeded by the 1987 general election and it ultimately did not become law. Its provisions were not reintroduced by the Conservative government following its re-election.

Instead, on 2 December 1987 in committee, Conservative MP David Wilshire proposed an amendment to the new Local Government Bill, as not yet passed, debated as Clause 27 and later as Clause 28, intended to be equivalent to the Earl of Halsbury's Bill.[30] The government agreed to support the tabling of the amendment in exchange for Knight forgoing her place on the Health and Medicines Bill standing committee;[31] the amendment received the support of the Ministers for Local Government, Michael Howard and Michael Portillo. On being tabled, a compromise amendment was introduced by Simon Hughes on 8 December 1987 that was debated in the House on 15 December 1987 and which was defeated by a majority of 87,[32] and the bill was approved on its first Commons debate that day. The bill was read a first time in the Lords two days later.[33]

Lord McIntosh of Haringey took up the mantle of Simon Hughes' amendments in the Lords' second reading, furthered by the Bishop of Manchester, Stanley Booth-Clibborn:

I should regret it if this Bill were to go through with this clause unamended. If it were to do so, I think it should certainly be confined to schools because otherwise there would be a real danger that some organisations which do good work in helping those with homosexual orientation, psychologically and in other ways, would be very much impeded.

A spectrum of literature across the ages was cited (in support of these compromise amendments) by Lord Peston. Nonetheless, the Bill passed second reading in the Lords before going to a whole house committee.[34]

In that debate Lord Boyd-Carpenter cited a book display, and proposals for "gay books" to be present in a children's home and a gay pride week to be permissible in schools by named London councils. However, on questioning, he said, "of course, 'promotion' can be treated in different ways. If the clause becomes law it will be a matter for the courts to interpret in the sensible way in which the courts do interpret the law." The SDP peer Viscount Falkland with Lord Henderson of Brompton proposed another compromise amendment, the so-called "Arts Council" amendment, and remarked "There is a suggestion in the clause that in no way can a homosexual have a loving, caring or responsible relationship".

Lord Somers countered:

One has only to look through the entire animal world to realise that it is abnormal. In any case, the clause as it stands does not prohibit homosexuality in any form; it merely discourages the teaching of it. When one is young at school one is very impressionable and may just as easily pick up bad habits as good habits.

The narrowing amendment failed by a majority of 55 voting against it; and the Lords voted the clause through the following day by a majority of 80.[35][36]

Michael Colvin MP thus on 8 March asked whether the minister, Christopher Chope, would discuss with the Association of London Authorities the level of expenditure by local authorities in London on support for gay and lesbian groups to which he replied:

No. Clause 28 of the Local Government Bill will ensure that expenditure by local authorities for the purpose of promoting homosexuality will no longer be permitted.[37]

The following day Tony Benn said during a debate in the House of Commons:

[...] if the sense of the word "promote" can be read across from "describe", every murder play promotes murder, every war play promotes war, every drama involving the eternal triangle promotes adultery; and Mr. Richard Branson's condom campaign promotes fornication. The House had better be very careful before it gives to judges, who come from a narrow section of society, the power to interpret "promote".[38]

Wilshire added that "there is an awful lot more promotion of homosexuality going on by local government outside classrooms", and the tempering amendments of that day's final debate were defeated by 53 votes.[39]

Section 28 became law on 24 May 1988. The night before, several protests were staged by lesbians, including abseiling into Parliament and an invasion of the BBC1's Six O'Clock News,[40] during which one woman managed to chain herself to Sue Lawley's desk and was sat on by the newsreader Nicholas Witchell.[41]

Controversy over applicability

editAs the Education (No. 2) Act 1986 gave school governors increased powers over the delivery of sex education, and Local Education Authorities no longer retained control over this, it has been argued that Section 28 was a redundant piece of legislation.[26] Section 28 was heavily influential in spite of this, and many of its opponents campaigned for its abolition as "a symbolic measure against intolerance."[42]

In response to widespread uncertainty about what the legislation permitted, including a common misconception that teachers were banned from discussing homosexuality with their students,[43] the National Union of Teachers released a statement to try to provide clarity for its members. The statement asserted that the legislation restricted “the ability of local authorities to support schools in respect of learning and educating for equality”, had an adverse impact on schemes designed to curb discrimination and made “it difficult for schools to prevent or address the serious problems that arise from homophobic bullying."[44] A government circular also stated that Section 28 would “not prevent the objective discussion of homosexuality in the classroom, nor the counselling of pupils concerned about their sexuality."[45] This contributed to further confusion around what was permitted under Section 28, with Jill Knight asserting that the aim of Section 28 “was to protect children in schools from having homosexuality thrust upon them."[46]

Both the Education Act 1996 and the Learning and Skills Act 2000 reduced Section 28's impact on sex education policy prior to its repeal, as the Secretary of State for Education solely regulated the delivery of sex education in England and Wales under these policies. However, the policy continued to have a significant impact on LGBT inequality across Britain.

Prosecutions and complaints

editNo local authorities were successfully prosecuted under Section 28.[6] However, there were legal attempts to use it to stop the funding of LGBT and HIV/AIDS prevention initiatives.

In May 2000, Glasgow resident Sheena Strain took Glasgow City Council to the Court of Session, with support from the Christian Institute. Strain objected to her council tax being used for what she viewed as the promotion of homosexuality. She particularly took issue with the provision of funding to the Scottish HIV/AIDS awareness organisation PHACE West, which produced and distributed a safe sex guide named ‘Gay Sex Now.’ Strain claimed that the guide was pornographic.[47]

Glasgow City Council countered this by arguing that the funding granted to PHACE West was for the purpose of preventing the further transmission of HIV/AIDS, and that the organisation was not promoting homosexuality. The council also emphasised that the Scottish Parliament had recently passed the Ethical Standards in Public Life etc. (Scotland) Act 2000, which would consequently repeal Section 28.

However, two months later, Strain dropped the case after reaching an agreement with the council. Under the agreement, Glasgow City Council was required to include a covering letter to grant recipients, stating that "You will not spend these monies for the purpose of promoting homosexuality nor shall they be used for the publication of any material which promotes homosexuality."[48]

Political response

editThe implementation of Section 28 divided the Conservative Party, heightening tensions between party modernisers and social conservatives.[49] In 1999, Conservative leader William Hague controversially sacked frontbencher Shaun Woodward for refusing to support the party line for Section 28's retention.[50] Woodward then defected to the Labour Party in opposition to the Conservatives' continued support of Section 28.[51] His dismissal also prompted Steven Norris and Ivan Massow to speak out against both Hague's decision to sack Woodward, and against Section 28. Ivan Massow, an openly gay man, defected to the Labour Party in August 2000.[52]

In the House of Lords, the campaign to repeal Section 28 was led by openly gay peer Waheed Alli.[53] The Liberal Democrats[54] and the Green Party[55] also opposed the legislation.

Repeal

editSection 2A was repealed in Scotland under the Ethical Standards in Public Life etc. (Scotland) Act 2000 on 21 June 2000. While 2 MSPs abstained from the vote, a majority of 99 voted for the repeal of Section 28 and 17 voted against it.[56]

Although New Labour's first attempt to repeal Section 28 in England and Wales was defeated following a campaign led by Baroness Young,[57] backbench MPs introduced a new amendment to repeal the legislation as part of another Local Government Bill in early 2003. This amendment was supported by the government and was passed by the Commons in March 2003, with a majority of 368 to 76.[58] As the impact of organised opposition within the House of Lords diminished following the death of Baroness Young, the legislation was subsequently passed with a majority of 180 to 130 in July 2003.[59] The Local Government Bill received Royal Assent as the Local Government Act 2003 on 18 September 2003, and Section 28 was removed from the statute books.[60]

Despite this, Kent County Council produced its own school curriculum guidelines as the county's “own form of Section 28.” The guidelines attempted to prohibit schools from “promoting homosexuality", while urging schools to emphasise the perceived importance of marriage and the nuclear family to their pupils.[61] The guidance distributed to local schools by Kent County Council was eventually quashed by the Equality Act 2010.

Support for Section 28

editThe main supporting argument for Section 28 was that it would protect children from being ‘indoctrinated’ into homosexuality.[62] Other arguments made in support of the legislation included that the ‘promotion’ of homosexuality undermined the importance of marriage,[26] the claim that the general public supported Section 28,[63] and that it did not prevent schools from discussing homosexuality objectively.[45] The Conservative Party whipped its members to support Section 28 in 2000, but allowed a free vote on its proposed repeal in 2003 following dissent from some of its members.

The Secondary Heads Association and NASUWT objected to repealing the legislation, stating in July 2000 that "it would be inappropriate to put parents and governors in charge of each school's sex education policy."[42] Religious groups including, but not limited to, The Salvation Army,[64] the Christian Institute,[65] Christian Action, Research and Education,[66] and the Muslim Council of Britain, also expressed their support for Section 28. Newspapers that strongly supported Section 28 included the Daily Mail, The Sun, The Daily Telegraph and the Daily Record.[67]

One of Section 28's most prominent supporters in Scotland was the businessman Brian Souter, who led the country's Keep the Clause campaign.[68] This included privately funding a postal ballot, after which he claimed that 86.8% of respondents were in favour of retaining Section 28. However, the poll received responses from less than one third of registered voters in Scotland.[69] The poll's result was dismissed by the Scottish Executive and acting Local Government and Communities Minister Wendy Alexander MSP,[70] and received further criticism from LGBT rights campaigner Peter Tatchell.[71] In contrast, Nicola Sturgeon of the SNP responded to the poll by stating that “the result confirmed that many Scots were concerned about repeal” and claimed that the debate regarding Section 28 was “difficult.”[72]

Opposition to Section 28

editThose who advocated for the repeal of Section 28 argued that the legislation actively discriminated against LGBT people, and put vulnerable young people at further risk from harm by failing to offer appropriate pastoral support or address homophobic bullying.[74] They also stated that Section 28 contributed to the further stigmatisation of LGBT people, particularly gay men, by framing them as inherently “predatory and dangerous to be allowed around children.”[75]

Section 28's implementation served to “galvanise [the disparate British LGBT rights movement] into action”, leading to the formation of campaign groups including Stonewall and OutRage!.[76] The Equality Network led the campaign in favour of repealing Section 28 in Scotland.[77] Other organisations that supported repealing the legislation included Gingerbread, the Family Planning Association and the Terrence Higgins Trust.[42]

The campaign to repeal Section 28 received media support from publications including Capital Gay, the Pink Paper, The Guardian,[74] the Gay Times,[78] The Independent and The Daily Mirror. Many people who were involved in the labour movement, including trade union members, also opposed the legislation.[79]

In February 1988,[74] John Shiers led a demonstration in Manchester in protest against Section 28. 25,000 people attended the protest.[80] The night before Section 28 came into effect in May 1988, several protests were staged by lesbian campaigners. These included abseiling into Parliament and invading the BBC1's Six O'Clock News. During the invasion, one woman chained herself to Sue Lawley's desk and was sat on by the newsreader Nicholas Witchell.[74]

A benefit show in support of the abolition of Section 28 also took place at Piccadilly Theatre on 5 June 1988, with over 60 performers. These included Pet Shop Boys, Sir Ian McKellen, Stephen Fry and Tilda Swinton.[81] Boy George[82] and Chumbawamba[83] also released singles in protest against Section 28.

After Section 28 was implemented, some local authorities continued to deliver training to education practitioners on how to deliver their services without discriminating against LGBT people. Manchester City Council also continued to sustain four officer posts directly involved in policy making and implementation, contributing to the 1992 report Section 28 of the Local Government Act 1988: a Guide for Workers in the Education Service, produced by Manchester City Council, May 1992.[84]

Legacy and cultural depictions

editSome prominent MPs who supported the bill when it was first introduced have since either expressed regret over their support, changed their stance due to different circumstances which have evolved over time, or have argued that the legislation is no longer necessary.

In an interview with gay magazine Attitude at the time of the 2005 general election, Michael Howard, then-Leader of the Conservative Party, commented: "[Section 28] was brought in to deal with what was seen to be a specific problem at the time. The problem was the kind of literature that was being used in some schools and distributed to very young children that was seen to promote homosexuality... I thought, rightly or wrongly, that there was a problem in those days. That problem simply doesn't exist now. Nobody's fussed about those issues any more. It's not a problem, so the law shouldn't be hanging around on the statute book".[85]

In February 2006, then-Conservative Party Chairman Francis Maude told Pinknews.co.uk that the policy, which he had voted for, was wrong and a mistake.[86]

In 2000, one year prior to his election to the House of Commons, Conservative Party member David Cameron repeatedly attacked the Labour Government's plans to abolish Section 28, publicly criticising then-Prime Minister Tony Blair as being "anti-family" and accusing him of wanting the "promotion of homosexuality in schools".[87] At the 2001 general election, Cameron was elected as the Member of Parliament for Witney; he continued to support Section 28, voting against its repeal in 2003.[88] The Labour Government were determined to repeal Section 28, and Cameron voted in favour of a Conservative amendment that retained certain aspects of the clause, which gay rights campaigners described as "Section 28 by the back door".[89] The Conservative amendment was unsuccessful, and Section 28 was repealed by the Labour Government without concession, with Cameron absent for the vote on its eventual repeal. However, in June 2009, Cameron, then-Leader of the Conservative Party, formally apologised for his party's introduction of the law, stating that it was a mistake and had been offensive to gay people.[90] He restated this belief in January 2010, proposing to alter Conservative Party policy to reflect his belief that equality should be "embedded" in British schools.[91]

Section 28 received renewed media attention in late 2011, when Michael Gove, in Clause 28 of the Model Funding Agreement for academies and free schools, added the stipulation that schools must emphasise “the importance of marriage”. Although the clause did not explicitly mention sexual orientation (same-sex marriage was not legal at the time), it prompted The Daily Telegraph to draw comparisons between the newly published clause and Section 28.[92]

A 2013 investigation conducted by LGBT activists and the British Humanist Association found that over 40 schools across Britain retained Sex and Relationship Education policies that either replicated the language of Section 28, or “[were] ambiguous on the issue” of teaching pupils about LGBT identities. Following this, the Department for Education announced its own investigation into the schools in question, stating that education providers were prohibited under DfE guidance from discriminating “on the grounds of sexual orientation.”[93]

Several academic studies on the impact of Section 28 show that it has continued to impact LGBT teachers and pupils in the years following its abolition[94][95] For example, a 2018 study by Catherine Lee[96] found that only 20% of participating LGBT teachers who had taught under Section 28 were open about their sexual orientations to their colleagues, compared to 88% of participants who qualified following Section 28's repeal. The study also found that 40% of the participants who worked in schools under Section 28 saw their sexual orientation as incompatible with their profession. In contrast, only 13% of those who received their training after Section 28 was repealed felt the same way.[97]

In 2016, research by Janine Walker and Jo Bates found that Section 28 still had a lasting effect on school libraries; the availability of LGBT literature, resources and student support was very limited, and participating librarians lacked the knowledge required to appropriately support LGBT young people.[98] A book chapter written by John Vincent stated that while conducting his research, he had met British library workers who assumed Section 28 was still in place. The book to which Vincent contributed was published in 2019.[99] A 2014 report on homophobic bullying in schools, published by Stonewall, found that 37% of primary school teachers and 29% of secondary school teachers did not know if they were allowed to teach lessons on LGBT issues.[100]

Recent British policy approaches to the provision of healthcare and pastoral support for young trans people, including a statement made by the acting Minister for Women and Equalities Liz Truss in 2020,[101] have also drawn comparisons to Section 28.[102][103]

Due to its longstanding impact on British LGBT people, Section 28 has inspired a number of cultural depictions. These include the 2013 drag comedy musical Margaret Thatcher Queen of Soho,[104] Chris Woodley's comedy drama play Next Lesson[105] and the 2022 film Blue Jean.[106] Russell T. Davies also included references to the legislation in the TV dramas Queer as Folk (1999) and It's A Sin (2021).[107]

See also

edit- LGBT rights in the United Kingdom

- LGBT History Month

- Briggs Initiative

- Thatcherism

- Premiership of Margaret Thatcher

- Censorship of LGBT issues

- Russian LGBT propaganda law – similar law introduced in Russia in 2013

- Florida Parental Rights in Education Act – similar law passed in Florida in 2022

- LGBT ideology-free zones – similar laws introduced by over 100 municipalities in Poland

- "Promotion of homosexuality"

Citations

edit- ^ "Local Government Act 1988". Retrieved 22 October 2024.

- ^ "Public Attitudes To Section 28". Ipsos. 1 February 2000. Retrieved 22 October 2024.

- ^ "Section 28 (2A in Scotland) 1988-2000". www.ourstoryscotland.org.uk. Retrieved 29 October 2024.

- ^ "Section 28: impact, fightback and repeal". The National Archives. Retrieved 22 October 2024.

- ^ "Knitting Circle 1989 Section 28 gleanings". Archived from the original on 18 August 2007. Retrieved 1 July 2006.

- ^ a b Greenland, Katy; Nunney, Rosalind (20 November 2008). "The repeal of Section 28: it ain't over 'til it's over". Pastoral Care in Education. 26 (4): 243–251. doi:10.1080/02643940802472171.

- ^ "The 20th anniversary of the repeal of section 28 of the Local Government Act 1988". House of Commons Library. Retrieved 22 October 2024.

- ^ "The 20th anniversary of the repeal of section 28 of the Local Government Act 1988". House of Commons Library. Retrieved 22 October 2024.

- ^ a b Lee, Catherine (2023). Pretended: Schools and Section 28. Historical, cultural and personal perspectives. Melton, United Kingdom: John Catt Educational Ltd. p. 92. ISBN 978-1915261694.

- ^ "Sexual Offences Act 1967", legislation.gov.uk, The National Archives, 1967 c. 60

- ^ "Regulating sex and sexuality: the 20th century". UK Parliament. Retrieved 25 October 2024.

- ^ Gallo RC (2006). "A reflection on HIV/AIDS research after 25 years". Retrovirology. 3 (1): 72. doi:10.1186/1742-4690-3-72. PMC 1629027. PMID 17054781.

- ^ "Timeline of The HIV and AIDS Epidemic". HIV.gov. Retrieved 25 October 2024.

- ^ "The History of AIDS and ARC" at the LSU Law Center

- ^ Herek, GM; Capitanio, JP; Widaman, KF (March 2002). "HIV-related stigma and knowledge in the United States: prevalence and trends, 1991–1999". American Journal of Public Health. 92 (3): 371–7. doi:10.2105/AJPH.92.3.371. PMC 1447082. PMID 11867313.

- ^ "Homosexuality". BSAS. Retrieved 5 May 2014.

- ^ "The School Curriculum (1981)". www.educationengland.org.uk. Archived from the original on 6 April 2010. Retrieved 1 July 2022.

- ^ a b Jones, Carol; Mahony, Pat, eds. (1989). Learning our lines: sexuality and social control in education. London: Women's Press. ISBN 978-0-7043-4199-9.

- ^ Davis, Jonathan; McWilliam, Rohan, eds. (1 February 2018). Labour and the Left in the 1980s. Manchester University Press. doi:10.7228/manchester/9781526106438.001.0001. ISBN 978-1-5261-2093-9.

- ^ Sunday Telegraph, 6 October 1985.

- ^ "Solidarity and Sexuality: Lesbians and Gays Support the Miners 1984–5". Oxford History Workshop Journal, Volume 77, Issue 1 (Spring 2014), pp. 240–262.

- ^ "LGBT Source Guide". Manchester City Council. Retrieved 24 May 2015.

- ^ "1985. Greater London Council: 'Changing the World'". Gay in the 80s. 29 October 2012. Retrieved 24 May 2015.

- ^ Buckle, Sebastian Charles. "Homosexual Identity in England, 1967-2004: Political Reform, Media and Social Change" (PDF). Retrieved 25 October 2024.

- ^ Davis, Glyn (2 January 2021). "'Gay Sex Kits': Lessons in the History of British Sex Education". Third Text. 35 (1): 145–160. doi:10.1080/09528822.2020.1861872. hdl:10023/25665. ISSN 0952-8822.

- ^ a b c Moran, Joe (2001). "Childhood Sexuality and Education: The Case of Section 28". Sexualities. 4 (1): 73–89. doi:10.1177/136346001004001004.

- ^ "Education (No. 2) Act 1986". legislation.gov.uk. Retrieved 25 October 2024.

- ^ "Local Government Bill (Hansard, 16 February 1988)". api.parliament.uk. Retrieved 25 October 2024.

- ^ "PROHIBITION ON PROMOTING HOMOSEXUALITY BY TEACHING OR BY PUBLISHING MATERIAL (Hansard, 15 December 1987)". api.parliament.uk. Retrieved 25 October 2024.

- ^ "The Local Government Bill [HL]: the 'section 28' debate" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 28 November 2007.

- ^ Street, John (25 December 1987). "The Diary". Tribune.

- ^ "Prohibition on Promoting Homosexuality by Teaching or by Publishing Material". Parliamentary Debates (Hansard). 15 December 1987. Retrieved 29 September 2015.

- ^ Hansard from Millbank Systems Archive 17 December 1987 col 906

- ^ Hansard from Millbank Systems Archive Second reading debate in Lords col 966

- ^ Hansard from Millbank Systems Archive Lords 1 February 1988 col 865–890

- ^ Hansard from Millbank Systems Archive Lords 2 February 1988 col 865–890

- ^ Hansard from Millbank Systems Archive 8 March 1988 – House of Commons

- ^ Roberts, Scott (14 March 2014). "Tony Benn: "Long before it was accepted I did support gay rights"". Pink News. Retrieved 22 May 2015.

- ^ Hansard from Millbank Systems Archive Lengthy debates of 9 March – House of Commons

- ^ "When gay became a four-letter word". BBC. 20 January 2000. Retrieved 4 January 2010.

- ^ "Nicholas Witchell". BBC. 1998. Archived from the original on 11 October 2003.

- ^ a b c "Section 28: An overview". BBC News. 25 July 2000. Retrieved 24 May 2015.

- ^ Biddulph, Max (2006). "Sexualities Equality in Schools: Why Every Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual or Transgender (LGBT) Child Matters". Pastoral Care in Education. 24 (2): 15–21. doi:10.1111/j.1468-0122.2006.00367.x.

- ^ "NUT on the Web". 25 December 2004. Archived from the original on 25 December 2004. Retrieved 25 October 2024.

- ^ a b "Section 28: impact, fightback and repeal". The National Archives. Retrieved 25 October 2024.

- ^ Brian Deer, Schools escape clause 28 in 'gay ban' fiasco (Sunday Times).

- ^ "Council halts gay group cash". BBC News. 14 May 2000. Retrieved 31 January 2021.

- ^ "Gay groups claim court victory". BBC News. 6 July 2000. Retrieved 31 January 2021.

- ^ Monahan, Martin (11 December 2018). "'Tory-normativity' and gay rights advocacy in the British Conservative Party since the 1950s". The British Journal of Politics and International Relations. 12 (1): 140–141. doi:10.1177/1369148118815407. S2CID 150298734.

- ^ "Tory MP sacked over gay row". BBC. 3 December 1999. Retrieved 4 January 2010.

- ^ Wintour, Patrick; McSmith, Andy (19 December 1999). "Top Tory defects to Labour". The Observer. ISSN 0029-7712. Retrieved 30 October 2024.

- ^ "Tory adviser defects to Labour". BBC. 2 August 2000. Retrieved 4 January 2010.

- ^ Kara, Maryam (16 September 2024). "Who is Lord Alli, the Life Peer and prominent Labour donor?". The Standard. Retrieved 30 October 2024.

- ^ "20 Years Since the Repeal of Section 28". lgbt.libdems.org.uk. Retrieved 30 October 2024.

- ^ "Generation 28". LGBTIQA+ Greens. 7 February 2021. Retrieved 30 October 2024.

- ^ "BBC News | SCOTLAND | MSPs abolish Section 28". news.bbc.co.uk. Retrieved 29 October 2024.

- ^ Langdon, Julia (7 September 2002). "Obituary: Lady Young of Farnworth". The Guardian. Retrieved 22 May 2015.

- ^ "The Public Whip — Local Government Bill — Maintain Prohibition on Promotion of Homosexuality (Section 28) - 10 Mar 2003 at 19:29". www.publicwhip.org.uk. Retrieved 29 October 2024.

- ^ "Section 28 to be repealed". 18 September 2003. Retrieved 29 October 2024.

- ^ "Stonewall". 17 April 2015. Archived from the original on 17 April 2015. Retrieved 29 October 2024.

- ^ "Kent votes for its own Section 28". The Independent. 21 July 2000.

- ^ DePalma, Renée; Atkinson, Elizabeth (7 December 2006). "The sound of silence: talking about sexual orientation and schooling". Sex Education. 6 (4): 333–349. doi:10.1080/14681810600981848.

- ^ Braunholtz, Simon (21 January 2000). "Public Attitudes (In Scotland) To Section 28". Ipsos MORI. Sunday Herald. Archived from the original on 23 November 2007.

- ^ "Salvation Army Letter to Scottish Parliament". Archived from the original on 31 January 2011. Retrieved 6 September 2011.

- ^ "Section 28: Briefing Paper". Christian Institute. Archived from the original on 4 August 2015. Retrieved 24 May 2015.

- ^ Merrick, Jane (30 March 2008). "Right-wing Christian group pays for Commons researchers". Independent. London. Archived from the original on 24 November 2009. Retrieved 22 March 2012.

CARE connections (list of MPs)

- ^ Wise, Sue (2000). "'"New Right" or "Backlash"? Section 28, Moral Panic and "Promoting Homosexuality"'". Sociological Research Online. 5 (1): 148–157. doi:10.5153/sro.452.

- ^ "BBC News | SCOTLAND | Souter defends Section 28 stance". news.bbc.co.uk. Retrieved 30 October 2024.

- ^ "Anti-gay legislation repealed in Scottish parliament". World Socialist Web Site. 7 July 2000. Retrieved 30 October 2024.

- ^ "BBC News | SCOTLAND | Poll supports S28 retention". news.bbc.co.uk. Retrieved 30 October 2024.

- ^ "Peter Tatchell: Think Again, Brian Souter". 9 August 2011. Archived from the original on 9 August 2011. Retrieved 30 October 2024.

- ^ "BBC News | SCOTLAND | Poll 'backs' Section 28". news.bbc.co.uk. Retrieved 30 October 2024.

- ^ "FindArticles.com - CBSi". findarticles.com.

- ^ a b c d Godfrey, Chris (27 March 2018). "Section 28 protesters 30 years on: 'We were arrested and put in a cell up by Big Ben'". The Guardian.

- ^ "Growing Up in Silence – A Short History of Section 28". twentysixdigital. 23 February 2021. Retrieved 30 October 2024.

- ^ "BBC News | SCOTLAND | When gay became a four-letter word". news.bbc.co.uk. Retrieved 30 October 2024.

- ^ Thirty-five years since Section 28 | Scottish Parliament TV. Retrieved 30 October 2024 – via www.scottishparliament.tv.

- ^ "Section 28 Archives". GAY TIMES. Retrieved 30 October 2024.

- ^ "Solidarity and Sexuality: Lesbians and Gays Support the Miners 1984–5". 25 January 2016. Archived from the original on 25 January 2016. Retrieved 30 October 2024.

- ^ Mottram, David; Cunningham, Moira (12 January 2012). "John Shiers obituary". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 30 October 2024.

- ^ "Before The Act Podcast". Retrieved 30 October 2024.

- ^ "By George* - No Clause 28". Discogs.

- ^ "Chumbawamba – Smash Clause 28! / Fight The Alton Bill!". Discogs.

- ^ "Manchester City Council - LGBT History - Real problems for real people". 11 June 2008. Archived from the original on 11 June 2008. Retrieved 30 October 2024.

- ^ Johann Hari – Archive Archived 17 March 2006 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Tories' gay stance 'was wrong'". BBC. 9 February 2006. Retrieved 4 January 2010.

- ^ "Channel 4 - News - Dispatches - Cameron: Toff At The Top". channel4.com. Retrieved 29 September 2015.

- ^ Patrick Wintour (2 July 2009). "David Cameron apologises to gay people for section 28". The Guardian. Retrieved 29 September 2015.

- ^ "Cameron attacked over gay rights record". TheGuardian.com. 4 October 2006.

- ^ "Cameron sorry for Section 28". The Independent. 22 October 2011.

- ^ Watt, Nicholas (28 January 2010). "Teaching about gay equality should be 'embedded' in schooling, says David Cameron". The Guardian. London. Retrieved 23 May 2010.

- ^ "Free schools and academies must promote marriage". Telegraph.co.uk. 3 December 2011. Retrieved 29 September 2015.

- ^ Nigel Morris (19 August 2013). "The return of Section 28: Schools and academies practising homophobic". The Independent. Retrieved 29 September 2015.

- ^ Nixon, David; Givens, Nick (29 May 2007). "An epitaph to Section 28? Telling tales out of school about changes and challenges to discourses of sexuality". International Journal of Qualitative Studies in Education. 20 (4): 449–471. doi:10.1080/09518390601176564. hdl:10036/42256.

- ^ Edwards, Lisa L.; Brown, David H. K.; Smith, Lauren (5 August 2014). "'We are getting there slowly': lesbian teacher experiences in the post-Section 28 environment". Sport, Education and Society. 21 (4): 299–318. doi:10.1080/13573322.2014.935317.

- ^ Lee, Catherine (2 November 2019). "Fifteen years on: the legacy of section 28 for LGBT+ teachers in English schools". Sex Education. 19 (6): 675–690. doi:10.1080/14681811.2019.1585800. ISSN 1468-1811.

- ^ "LGBT teachers who taught under Section 28 still 'scarred' report finds". 12 March 2019.

- ^ Walker, Janine; Bates, Jo (2016). "Developments in LGBTQ provision in secondary school library services since the abolition of Section 28". Journal of Librarianship and Information Science. 48 (3): 269–283. doi:10.1177/0961000614566340. ISSN 0961-0006. S2CID 36944979.

- ^ Vincent, John (2019). "Moving into the Mainstream: Is that Somewhere We Want to Go in the United Kingdom?". LGBTQ+ librarianship in the 21st century : emerging directions of advocacy and community engagement in diverse information environments. Bharat Mehra. United Kingdom. ISBN 978-1-78756-473-2. OCLC 1098173907.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ "The Long Shadow of Section 28".

- ^ "Minister for Women and Equalities Liz Truss sets out priorities to Women and Equalities Select Committee". GOV.UK. 22 April 2020. Retrieved 31 October 2024.

- ^ "I'm a trans woman who grew up under Section 28 - I worry it could comeback". 11 May 2020.

- ^ Russell, Laura (23 April 2020). "Why we're worried about the Government's statement on trans rights legislation". Stonewall. Retrieved 21 October 2022.

- ^ "Margaret Thatcher Queen of Soho - Theatre503 Margaret Thatcher Queen of Soho - Book online or call the box office 020 7978 7040". theatre503.com. Archived from the original on 27 October 2013. Retrieved 29 September 2015.

- ^ Machin, Freddie (1 May 2019). "Next Lesson by Chris Woodley". Drama And Theatre. Retrieved 31 October 2024.

- ^ "Blue Jean: The lesbian teachers who inspired film about Section 28". BBC News. 10 February 2023. Retrieved 12 February 2023.

- ^ Davies, Russell T (January 2021). "Episode 4". It's A Sin. Channel 4.

General and cited sources

edit- Text of the Local Government Act 1986 as in force today (including any amendments) within the United Kingdom, from legislation.gov.uk.

- Text of the Local Government Act 1988 as in force today (including any amendments) within the United Kingdom, from legislation.gov.uk.

- "Local Government Act (1988)". Section 28. Retrieved 9 February 2005. (Full text of the section)

- "Knitting Circle". Section 28 1989 Gleanings. Archived from the original on 14 November 2006. Retrieved 21 February 2005. (Newspaper clippings from 1989 demonstrating use of Section 28 to close LGBT student groups and cease distribution of material exploring gay issues)

- "The Guardian (31 January 2000)". Jenny, Eric, Martin ... and me. London. 31 January 2000. Retrieved 9 February 2005. (article on Section 28 and the book that caused the controversy, Jenny lives with Eric and Martin, by author, Susanne Bosche)

- "Knitting Circle (9 August 2001)". Section 28. Archived from the original on 12 December 2006. Retrieved 21 February 2005. (History of Section 28 with notes on attempted legislation that led up to the final amendment)

- "Gay and Lesbian Humanist Society". Section 28. Archived from the original on 8 March 2005. Retrieved 28 February 2005. (Notes and links on Section 28 from a humanist perspective, with notes on usage of the Section 2a name.)

- "When gay became a four-letter word". BBC News. 20 January 2000. Retrieved 4 June 2005. (Potted history of Section 28 from 2000)

- "USSU National Policy Issues (28 January 1988)". Section 5.2.1 Stop Clause 28 (of Local Government Bill). Archived from the original on 5 May 2005. Retrieved 29 June 2005. (USSU National Policy Issues detailing notes on heightened violence against gays and lesbians in the lead-up to Section 28 enactment)

- "Tory adviser defects to Labour". BBC News. 2 August 2000. Retrieved 21 February 2005. (Report of gay Conservative Ivan Massow's defection to the Labour Party)

- "Scotsman.com News". Nicholas Witchell: A Celebration. Archived from the original on 28 December 2005. Retrieved 18 May 2005. (Nicholas Witchell's encounter with Section 28 protesters)

- "National Union of Teachers (5 April 2003)". NUT campaign to repeal Section 28. Archived from the original on 25 December 2004. Retrieved 9 February 2005. (Statement by the NUT on the controversy of applicability of Section 28)

- "The Sunday Times (London) (29 May 1988)". Schools Escape Clause 28 in 'Gay Ban' Fiasco. Retrieved 9 February 2005. (Knight's response to the controversy of applicability of Section 28)

- "(30 May 2000)". Poll supports S28 retention. 30 May 2000. Retrieved 19 February 2005. (Brian Souter's Keep the Clause campaign runs unofficial poll to discredit reformers)

- "The Christian Institute". Briefing Paper – Section 28. Archived from the original on 4 August 2015. Retrieved 9 May 2005. (Summary of points in support of Section 28)

External links

edit- Text of the Local Government Act 1988 as in force today (including any amendments) within the United Kingdom, from legislation.gov.uk.

- "The Section 28 Battle". BBC News. 24 July 2000. Retrieved 25 March 2003.

- Royal Assent of the Local Government 1988