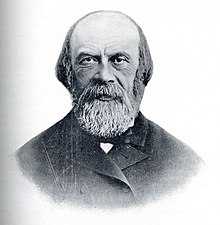

Lev Semyonovich Tsenkovsky, also Leon Cienkowski (Russian: Лев Семёнович Ценковский; 1 October [O.S. 13 October] 1822 – 25 September [O.S. 7 October] 1887) was a Russian botanist, protozoologist, and bacteriologist. He was a corresponding member of the Saint Petersburg Academy of Sciences (1881).

Lev Tsenkovsky | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | 1 October 1822 |

| Died | 25 September 1887 (aged 64) |

| Alma mater | Saint Petersburg Imperial University |

Lev Tsenkovsky graduated from Saint Petersburg Imperial University in 1844. As a professor, he taught at the Demidov Lyceum in Yaroslavl (1850-1854), Saint Petersburg University, Imperial Novorossiya University in Odessa (1865-1871), and Imperial Kharkov University (1872-1887). Lev Tsenkovsky was one of the pioneers of the ontogenetic method of studying lower plants and lower animals. Also, he was developing a concept on genetic unity of flora and fauna. Tsenkovsky was one of the advocates of the teachings of Charles Darwin. He is known to have suggested methods of developing an effective anthrax vaccine. Lev Tsenkovsky contributed to the organization of the first vaccination station in Kharkov in 1887.

Biography

editTsenkovsky, a Pole by nationality, was born into a very poor and poorly educated family. However, his mother, understanding the importance of education, did everything in her power to provide her son with a good education. After completing the course at the Warsaw Gymnasium in 1839, he was sent as a scholarship recipient from the Congress Poland to the St. Petersburg Imperial University. Initially enrolled in the mathematical department of the physics and mathematics faculty, he soon switched to the natural sciences, particularly focusing on botany.

In 1844, Tsenkovsky graduated from the university course with a candidate’s degree in natural sciences and was left at St. Petersburg University, and two years later received a master’s degree for defending his dissertation “Several facts from the history of the development of conifers.”

A year later, having received a business trip, Tsenkovsky went with Colonel Kovalevsky to Central Africa (to northeastern Sudan, to the mouth of the White Nile) and spent two years on the journey.[1] There he collected rich material from the flora and fauna of Sudan. The results of the work were published in Geographical Gazette[a] (1850) and in Gazeta Warszawska (1853).[2]

In 1850, Tsenkovsky was appointed professor in the department of natural sciences at the Yaroslavl Demidov Lyceum, where he remained until 1855, then took the department of botany at St. Petersburg University. The following year, Tsenkovsky defended his dissertation for the degree of Doctor of Botany.

The unfavorable St. Petersburg climate had a harmful effect on Tsenkovsky’s already poor health, and in 1859 he went abroad[where?], where he stayed, constantly engaged in scientific research, for about four years.

In 1865, with the opening of the Imperial Novorossiya University (now the Odessa National University), Tsenkovsky was invited as a professor of botany. In Odessa, he took an active part in the founding of the Novorossiya Naturalists Society and was elected its first president. At the first meeting of the society in 1870, Tsenkovsky proposed the creation of a biological station in Sevastopol in pursuance of the resolution of the Second Congress of Russian Naturalists and Doctors, adopted in 1869. The Sevastopol biological station was officially opened the following year, 1871.[3]

During this period, he began research in the field of microbiology. Tsenkovsky's work established scientific directions that found their development in experiments of professor of botany F. M. Kamensky - the process of symbiosis of fungi with higher plants; Professor of Botany F. M. Porodko – physiology of microorganisms, yeast fermentation.[2]

In 1869 he moved to the Imperial Kharkov University.

Tsenkovsky studied lower organisms (ciliates, lower algae, fungi, bacteria, etc.) and a number of precise studies established a genetic connection between monads and myxomycetes, heliozoa and radiolaria, flagellates and palmelliform algae, etc. Already in his test lecture Tsenkovsky expressed a correct and for that time bold view that, as his own research convinced him, ciliates are the protozoa organisms, consisting of a lump of protoplasm, and that Ehrenberg’s then dominant view of ciliates as highly organized animals is incorrect.

His doctoral dissertation “On lower algae and ciliates,” dedicated to the morphology and history of the development of various microscopic organisms (Sphacroplea annulina, Achlya prolifera, Actinosphaerium, etc.) can be considered one of the first and classic works in this area. Already in this work the idea was expressed that there is no sharp boundary between the plant and animal worlds, and that this is precisely what is confirmed by the organization of the studied forms. Subsequent studies by Tsenkovsky confirm this opinion, which has now become an axiom.

His most important research on the history of the development of myxomycetes (slime fungi) and monads gave him the opportunity to bring both together. Very important is the discovery of Tsenkovsky in algae, flagellates, and subsequently in bacteria, the palmelle state, that is, the ability of cells to secrete mucus and form mucus colonies.

Many important works of Tsenkovsky are devoted to lower algae and fungi belonging to the plant kingdom, and amoebas, sunfishes (Actinosphaerium, Clathrulina, etc.), flagellates (Noctiluca, chrysomonads, etc.), radiolaria, ciliated ciliates (objection to Acineta Stein's theory of 1855), relating to the animal kingdom, so his merits in botany and zoology are equally great.

Tsenkovsky then devoted the last period of his activity to a completely new branch of knowledge – bacteriology. He greatly contributed to the development of practical bacteriology in Russia, in particular he improved the methods of vaccination against anthrax.[4] The German botanist Julius Sachs called him the founder of scientific bacteriology.

In 1880, Tsenkovsky undertook a trip to the White Sea, and was mainly engaged in collecting microorganisms on the Solovetsky Islands, with their subsequent study in the laboratory.

Bibliography

edit- “Zur Befruchtung d. Juniperus communis" ("Bull. soc. nat. Moscou". 1853, No. 2)

- “Bemerkungen liber Stein’s Acineten Lehre” (“Bull. Acad. S.-Petersb.”, 1855, XIII)

- "Algologische Studien" ("Bot. Zeitschrift", 1855)

- “On spontaneous generation” (St. Petersburg, 1855);

- “Zur Genesis eines einzeiligen Organismus” (“Bull. Acad. S.-Petersb.”, 1856. XIV);

- “Ueber meinen Beweis für die Generatia primaria” (ibid., 1858, XVII);

- “Ueber Cystenbildung hei Infusorien” (“Zeitschr. wiss. Zoologie”, 1855, XVI);

- “Rhisidium Confervae Glomeratae” (“Bot. Zeit.”, 1857);

- “Die Pseudogonidien” (“Jahrb. wiss. Bot.”, 1852, I);

- “Ueber parasitische Schläuche auf Crustaceen und einigen Insectenlarven” (“Bot. Zeitschr.”, 1861);

- “Zur Entwickelungsgeschichte der Myxomyceten” (“Jahrb. wiss. Bot.”, 1862, XIII);

- "Das Plasmodium" (ibid., 1863, III);

- “Ueber einige Chlorophyllhaltige Gloeocapsen” (“Bot. Zeit.”, 1865);

- “Beiträge z. Kentniss d. Monaden" ("Arch. micr. Anatomie", 1865, I);

- “Ueber den Bau und die Entwickelung der Labyrinthulaceen” (ibid., 1867, III);

- "Ueber die Clathrulina" (ibid.);

- “Ueber Palmellaceen und einige Flagellaten” (ibid., 1870, VI; also “Proceedings of the 2nd Congress of Russian Naturalists and Doctors”);

- “Ueber Schwärmerbildung bei Noctiluca miliaris” (“Arch. micr. Anat”, 1871, VII);

- “Ueber Schwärmerbildung bei Radiolarien” (ib.);

- “Die Pilze der Kahmhaut” (“Bull. Acad. S.-Petersb.”, 1872, XVII);

- "Ueber Noctiluca miliaris" (ibid., 1873, IX);

- “On the genetic connection between Mycoderma vini, Pénicillium viride and Domatium pullullans” (“Proceedings of the 4th Congress of Russian Naturalists and Doctors”, 1872);

- “Ueber Palmellen-Zustand bei Stigeocionium” (“Bot. Zeit.”, 1876);

- “On the morphology of the family. Ulothrichineae" (“Tr. general. test. nature. Kharkov. Univ.”, 1877, the same “Bull. Acad. S.-Petersb.”, 1876);

- “Ueber einige Rhizopoden und verwandte Organismen” (“Arch. micr. Anat.”, 1876, vol. XII);

- “Zur Morphologie der Bactérien” (“Mém. Acad. S.-Petersb.”, ser. 7, vol. XXV);

- “Report on the White Sea excursion of 1880.” (“Proceedings of St. Petersburg. General. Natural.”, 1881, XII);

- “Microorganisms. Bacterial formations" (Khark., 1882);

- “On Pasteur’s grafting” (“Proceedings of Voln. Ekonom. Obshch.”, 1883, 1884);

- “Report on large-scale anthrax vaccinations” (“Collected Kherson Zemstvos”, III, 1886).

- Tsenkovsky’s anniversary speech, which is autobiographical in nature (see “Southern Region”, 1886).

References

edit- ^ Николай Баландинский (2003). "Первая русская экспедиция в Африку: Егор Ковалевский и Лев Ценковский, 1847-1848 гг". География.ру - Страноведческая журналистика. Archived from the original on 2008-02-11. Retrieved 2008-06-29.

- ^ a b "Ценковський Лев Семенович" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 2020-10-19. Retrieved 2020-11-17.

- ^ Тумаркин Д. Д. (2011). Белый папуас: Н. Н. Миклухо-Маклай на фоне эпохи. М: Восточная литература. ISBN 978-5-02-036470-7.

- ^ Василий Калита (2015-03-27). "Профессора Ценковского называли украинским Пастером". «Здоров’я України IНФОМЕДІА». Archived from the original on 2010-01-31. Retrieved 2008-06-29.