Historiography of the Christianization of the Roman Empire

The growth of Christianity from its obscure origin c. 40 AD, with fewer than 1,000 followers, to being the majority religion of the entire Roman Empire by AD 400, has been examined through a wide variety of historiographical approaches.

Until the last decades of the 20th century, the primary theory was provided by Edward Gibbon in The History of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire, published in 1776. Gibbon theorized that paganism declined from the second century BC and was finally eliminated by the top-down imposition of Christianity by Constantine, the first Christian emperor, and his successors in the fourth century AD.

For over 200 years, Gibbon's model and its expanded explanatory versions—the conflict model and the legislative model—have provided the major narrative. The conflict model asserts that Christianity rose in conflict with paganism, defeating it only after emperors became Christian and were willing to use their power to require conversion through coercion. The legislative model is based on the Theodosian Code published in AD 438.

In the last decade of the 20th century and into the 21st century, multiple new discoveries of texts and documents, along with new research (such as modern archaeology and numismatics), combined with new fields of study (such as sociology and anthropology) and modern mathematical modeling, have undermined much of this traditional view. According to modern theories, Christianity became established in the third century, before Constantine, paganism did not end in the fourth century, and imperial legislation had only limited effect before the era of the Eastern emperor Justinian I (reign 527 to 565).[1][2][3][4] In the twenty-first century, the conflict model has become marginalized, while a grassroots theory has developed.[5][6]

Alternative theories involve psychology or evolution of cultural selection, with many 21st-century scholars asserting that sociological models such as network theory and diffusion of innovation provide the most insight into the societal change.[7][8] Sociology has also generated the theory that Christianity spread as a grass roots movement that grew from the bottom up; it includes ideas and practices such as charity, egalitarianism, accessibility and a clear message, demonstrating its appeal to people over the alternatives available to most in the Roman Empire of the time. The effects of this religious change are seen as mixed and are debated.

History

editOf historiography

editThe standard view of paganism (traditional city-based polytheistic Graeco-Roman religion) in the Roman empire has long been one of decline beginning in the second and first centuries BC. Decline was interrupted by the short-lived 'Restoration' under the emperor Augustus (reign 27 BC – AD 14), then it resumed. In the process of decline, it has been thought that Roman religion embraced emperor worship, the 'oriental cults' and Christianity as symptoms of that decline.[9] Christianity emerged as a major religious movement in the Roman Empire, the barbarian kingdoms of the West, in neighboring kingdoms and some parts of the Persian and Sassanian empires.[10]

The major narrative concerning the rise of Christianity has, for over 200 years since its publication in 1776, been taken primarily from historian Edward Gibbon's Decline and Fall.[11] Gibbon had seen Constantine as driven by "boundless ambition" and a desire for personal glory to force Christianity on the rest of the empire in a cynical, political move thereby achieving, "in less than a century, the final conquest of the Roman empire".[12][13] It wasn't until 1936 that scholars such as Arnaldo Momigliano began to question Gibbon's view.[14]

In 1953, art historian Alois Riegl provided the first true departure, writing that there were no qualitative differences in art and no periods of decline throughout Late Antiquity.[15] In 1975, the concept of "history" was expanded to include sources outside ancient historical narrative and traditional literary works.[16] The evidentiary basis expanded to include legal practices, economics, the history of ideas, coins, gravestones, architecture, archaeology and more.[17][18] In the 1980s, syntheses began to pull together the results of this more detailed work.[19] In the closing quarter of the twentieth century, scholarship advanced significantly.[20]

Gibbon's historical sources were almost exclusively Christian literary documents.[21] These documents have a starkly supernatural quality, and many are hagiographical. They present the rise of Christianity in terms of conquest which had taken place in Heaven where the Christian God had defeated the pagan gods. Fourth century Christian writers depict Constantine's conversion as proof of that defeat, and Christian writings are filled with proclaiming their heavenly "triumph".[22]

According to Peter Brown: "The belief that Late Antiquity witnessed the death of paganism and the triumph of monotheism, ... is not actual history but is, instead, a "representation" of the history of the age created by "a brilliant generation of Christian writers, polemicists and preachers in the last decade of this period".[23] Ramsay MacMullen writes that: "We may fairly accuse the historical record of having failed us, not just in the familiar way, being simply insufficient, but also through being distorted".[24] Historian Rita Lizzi Testa adds "Transcending the limitations of the Enlightenment's interpretive categories" has meant restructuring understanding of the late Roman empire.[25] The result has been a radically altered picture.[17] According to the Oxford Handbook of Late Antiquity, scholars have largely abandoned Gibbon's views of decline, crisis and fall.[26]

Most contemporary scholars, such as philosophy professor Antonio Donato, consider current understanding to be more precise and accurate than ever before.[20] However, this "new view" has also been criticized, and the decline of paganism has been taken up again by some scholars.[27][28] Not all the classic themes have lost their value in current scholarship. In 2001, Wolf Liebeschuetz suggested that some special situations, such as the era between the imperial age and the Middle ages, require the concept of crisis to be understood.[29]

Roman religion

editReligion in Graeco-Roman times differed from religion in modern times. In the early Roman Empire religion was polytheistic and local. It was not focused on the individual but was focused on the good of the city: it was a civic religion in which ritual was the main form of worship. Politics and religion were intertwined, and many public rituals were performed by public officials. Respect for ancestral custom was a large part of polytheistic belief and practice, and members of the local society were expected to take part in public rituals.[30][31]

Roman historians, such as the classicist J. A. North, have written that Roman imperial culture began in the first century with religion embedded in the city-state, then gradually shifted to religion as a personal choice.[32] Roman religion's willingness to adopt foreign gods and practices into its pantheon meant that, as Rome expanded, it also gained local gods which offered different characteristics, experiences, insights, and stories.[33][34] There is consensus among scholars that religious identity became increasingly separated from civic and political identity, progressively giving way to the plurality of religious options rooted in other identities, needs and interests.[35][33]

Formerly, scholars believed that this plurality contributed to the slow decline of polytheism that began in the second century BC, and this axiom was rarely challenged.[36][37] James B. Rives, classics scholar, has written that:

Evidence for neglect and manipulation could readily be found, ... But, as more recent scholars have argued, this evidence has often been cited without proper consideration of its context; at the same time, other evidence that presents a different picture has been dismissed out of hand.[38][39]

Context and other evidence

editAfter 1990, evidence expanded and altered the picture of late antique paganism.[40] For example, private cults of the emperor were previously greatly underestimated.[41] For many years, the imperial cult was regarded by the majority of scholars as both a symptom and a cause of the final decline of traditional Graeco-Roman religion. It was assumed this kind of worship of a man could only be possible in a system that had become completely devoid of real religious meaning. It was, therefore, generally treated as a "political phenomenon cloaked in religious dress".[42] However, scholarship of the twenty-first century has shifted toward seeing it as a genuine religious phenomenon.[42]

Classical scholar Simon Price used anthropological models to show that the imperial cult's rituals and iconography were elements of a way of thinking that people formed as a means of coming to terms with the tremendous power of Roman emperors.[43] The emperor was "conceived in terms of honors ... as the representation of power" personifying the intermediary between the human and the divine.[44][42] According to Rives, "Most recent scholars have accepted Price's approach".[41]

Recent literary evidence reveals emperor worship at the domestic level with his image "among the household gods".[45] Innumerable small images of emperors have been found in a wide range of media that are being reevaluated as religiously significant.[45] Rives adds that "epigraphic evidence reveals the existence of numerous private associations of 'worshippers of the emperor' or 'of the emperor's image', many of which seem to have developed from household associations".[45] It is now recognized that these private cults were "very common and widespread indeed, in the domus, in the streets, in public squares, in Rome itself (perhaps there in particular) as well as outside the capital".[45]

Spread of Christianity

editOrigin

editChristianity emerged as a sect of Second Temple Judaism in Roman Judaea, part of the syncretistic Hellenistic world of the first century AD, which was dominated by Roman law and Greek culture.[46] It started with the ministry of Jesus, who proclaimed the coming of the Kingdom of God.[47] After his death by crucifixion, some of his followers are said to have seen Jesus, and proclaimed him to be alive and resurrected by God.[48][49]

When Christianity spread beyond Judaea, it first arrived in Jewish diaspora communities.[50] The early Gospel message spread orally, probably originally in Aramaic,[51] but almost immediately also in Greek.[52] Within the first century, the messages began to be recorded in writing and spread abroad.[53][54] The earliest writings are generally thought to be those of the Apostle Paul who spoke of Jesus as both divine and human.[55] The degree of each of these characteristics later became cause for controversy beginning with Gnosticism which denied Jesus' humanity and Arianism which downgraded his divinity.[56]

Christianity began to expand almost immediately from its initial Jewish base to Gentiles (non-Jews). Both Peter and Paul are sometimes referred to as Apostles to the Gentiles. This led to disputes with those requiring the continued observance of the whole Mosaic law including the requirement for circumcision.[57][58] James the Just called the Council of Jerusalem (around 50 AD) which determined that converts should avoid "pollution of idols, fornication, things strangled, and blood" but should not be required to follow other aspects of Jewish Law (KJV, Acts 15:20–21).[59] As Christianity grew in the Gentile world, it underwent a gradual separation from Judaism.[60][61]

Christianization was never a one-way process.[62] Instead, there has always been a kind of parallelism as it absorbed indigenous elements just as indigenous religions absorbed aspects of Christianity.[63] Michelle Salzman has shown that in the process of converting the Roman Empire's aristocracy, Christianity absorbed the values of that aristocracy.[64] Several early Christian writers, including Justin (2nd century), Tertullian, and Origen (3rd century) wrote of Mithraists "copying" Christian beliefs.[65] Christianity adopted aspects of Platonic thought, names for months and days of the week – even the concept of a seven-day week – from Roman paganism.[66][67] Bruce David Forbes says that "Some way or another, Christmas was started to compete with rival Roman religions, or to co-opt the winter celebrations as a way to spread Christianity, or to baptize the winter festivals with Christian meaning in an effort to limit their [drunken] excesses. Most likely all three".[68] Some scholars have suggested that characteristics of some pagan gods — or at least their roles — were transferred to Christian saints after the fourth century.[69] Demetrius of Thessaloniki became venerated as the patron of agriculture during the Middle Ages. According to historian Hans Kloft, that was because the Eleusinian Mysteries, Demeter's cult, ended in the 4th century, and the Greek rural population gradually transferred her rites and roles onto the Christian saint Demetrius.[69]

Reception and growth in Roman society

editFor the followers of traditional Roman religions, Christianity was seen as an odd entity, not quite Roman, but not quite barbarian either.[70] Christians criticized fundamental beliefs of Roman society, and refused to participate in rituals, festivals and the imperial cult.[70][71][72] They were a target for suspicion and rumor, including rumors that they were politically subversive and practiced black magic, incest and cannibalism.[73][74] Conversions tore families apart: Justin Martyr tells of a pagan husband who denounced his Christian wife, and Tertullian tells of children disinherited for becoming Christians.[75] Despite this, for most of its first three centuries, Christianity was usually tolerated, and episodes of persecution tended to be localized actions by mobs and governors.[76] Suetonius and Tacitus both record emperor Nero persecuting Christians in the mid-1st century, however this only occurred within Rome itself. There were no empire-wide persecutions until Christianity reached a critical juncture in the mid-third century.[77]

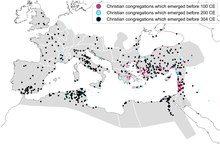

Beginning with less than 1000 people, by the year 100, Christianity had grown to perhaps one hundred small household churches consisting of an average of around seventy (12–200) members each.[78] These churches were a segmented series of small groups.[79] By 200, Christian numbers had grown to over 200,000 people, and communities with an average size of 500–1000 people existed in approximately 200–400 towns. By the mid-3rd century, the little house-churches where Christians had assembled were being succeeded by buildings adapted or designed to be churches complete with assembly rooms, classrooms, and dining rooms.[80] The earliest dated church building to survive comes from around this time.[81]

In his mathematical modelling, Rodney Stark estimates that Christians made up around 1.9% of the Roman population in 250.[82] That year, Decius made it a capital offence to refuse to make sacrifices to Roman Gods, although it did not outlaw Christian worship and may not have targeted Christians specifically.[83] Valerian pursued similar policies later that decade. These were followed by a 40-year period of tolerance known as the "little peace of the Church". Christianity grew in that time to have a major demographic presence. Stark, building on earlier estimates by theologian Robert M. Grant and historian Ramsay MacMullen, estimates that Christians made up around ten percent of the Roman population by 300.[82] The last and most severe official persecution, the Diocletianic Persecution, took place in 303–311.[72]

Under Constantine and his Christian successors

editConstantine, who gained full control of the empire in 312, became the first Christian emperor. Although he was not baptised until shortly before his death, he pursued policies that were favorable to Christianity. The Edict of Milan of 313 ended official persecutions of Christianity extending toleration to all religions. Constantine supported the Church financially, built basilicas, granted privileges to clergy which had previously been available only to pagan priests (such as exemption from certain taxes), promoted Christians to high office, and returned property confiscated during the persecutions.[85] He also sponsored the First Council of Nicea to codify aspects of Christian doctrine.[86]

According to Stark, the rate of Christianity's growth under its first Christian emperor in the 4th century did not alter (more than normal regional fluctuations) from its rate of growth in the first three centuries. However, since Stark describes an exponential growth curve, he adds that this "probably was a period of 'miraculous seeming' growth in terms of absolute numbers".[87] By the middle of the century, it is likely that Christians comprised just over half of the empire's population.[82]

A study by Edwin A. Judge, social scientist, shows that a fully organized church system existed before Constantine and the Council of Nicea. From this, Judge concludes "the argument Christianity owed its triumph to its adoption by Constantine cannot be sustained".[2] Critical mass had been achieved in the hundred years between 150 and 250 which saw Christianity move from fewer than 50,000 adherents to over a million.[88] There was a significant rise in the absolute number of Christians in the rest of the third century.[89][90] Classics professor Seth Schwartz states the number of Christians in existence by the end of the third century indicates Christianity's successful establishment predated Constantine.[91]

Under Constantine and his sons, certain pagan rites, including animal sacrifice and divination, began being deprived of their previous position in Roman civilization.[92][93] Yet other pagan practices were tolerated, Constantine did not stop the established state support of the traditional religious institutions, nor did society substantially change its pagan nature under his rule.[94] Constantine's policies were largely continued by his sons though not universally or continuously.[95]

Peter Brown has written that, "it would be profoundly misleading" to claim that the cultural and social changes that took place in Late Antiquity reflected "in any way" a process of Christianization.[96] Instead, the "flowering of a vigorous public culture that polytheists, Jews and Christians alike could share... [that] could be described as Christian "only in the narrowest sense" developed. It is true that blood sacrifice played no part in that culture, but the sheer success and unusual stability of the Constantinian and post-Constantinian state also ensured that "the edges of potential conflict were blurred... It would be wrong to look for further signs of Christianization at this time. It is impossible to speak of a Christian empire as existing before Justinian". [97]

Theodosius I

editIn the centuries following his death, Theodosius I (347 – 395) gained a reputation as the emperor who targeted and eliminated paganism in order to establish Nicene Christianity as the official religion of the empire. Modern historians see this as an interpretation of history rather than actual history. Cameron writes that Theodosius's predecessors Constantine, Constantius, and Valens had all been semi-Arians; therefore, Christian literary tradition gave the orthodox Theodosius most of the credit for the final triumph of Christianity.[98][99][100][note 1]

In keeping with this view of Theodosius, some previous scholars interpreted the Edict of Thessalonica (380) as establishing Christianity as the state religion.[109] German ancient historian Karl Leo Noethlichs writes that the Edict of Thessalonica did not declare Christianity to be the official religion of the empire, and it gave no advantage to Christians over other faiths.[110] The Edict was addressed to the people of the city of Constantinople, it opposed Arianism, attempted to establish unity in Christianity and suppress heresy.[111][note 2] Hungarian legal scholar Pál Sáry says it is clear from mandates issued in the years after 380 that Theodosius had made no requirement in the Edict for pagans or Jews to convert to Christianity: "In 393, the emperor was gravely disturbed that the Jewish assemblies had been forbidden in certain places. For this reason, he stated with emphasis that the sect of the Jews was forbidden by no law."[114]

There is little, if any, evidence that Theodosius I pursued an active policy against the traditional cults, though he did reinforce laws against sacrifice, and write several laws against all forms of heresy.[100][115] Scholars generally agree that Theodosius began his rule with a cautiously tolerant attitude and policy toward pagans. Three successive laws issued in February 391 and in June and November of 392 have been seen by some as a marked change in Theodosius' policy putting an end to tolerance.[116] Roman historian Alan Cameron has written on the laws of 391 and June 392 as being responses to local appeals that restated, as instructions, what had been requested by the locals. Cameron says these laws were never intended to be binding on the population at large.[117]

The law of 8 November 392 has been described by some as the universal ban on paganism that made Christianity the official religion of the empire.[118][119] The law was addressed only to Rufinus in the East, it makes no mention of Christianity, and it focuses on practices of private domestic sacrifice: the lares, the penates and the genius.[120][121] The lares is the god who takes care of the home, write archaeologists Konstantinos Bilias and Francesca Grigolo.[122] The genius was fixed on a person, usually the head of the household.[123] The penates were the divinities who provided and guarded the food and possessions of the household.[120] Sacrifice had largely ended by the time of Julian (361-363), a generation before the law of November 392 was issued, but these private, domestic, sometimes daily, sacrifices were thought to have "slipped out from under public control".[124][125][126] Sozomen, the Constantinopolitan lawyer, wrote a history of the church around 443 where he evaluates the law of 8 November 392 as having had only minor significance at the time it was issued.[127]

Historical and literary sources, excepting the laws themselves, do not support the view that Theodosius created an environment of intolerance and persecution of pagans.[128][129] During the reign of Theodosius, pagans were continuously appointed to prominent positions, and pagan aristocrats remained in high offices.[114] During his first official tour of Italy (389–391), the emperor won over the influential pagan lobby in the Roman Senate by appointing its foremost members to important administrative posts.[130] Theodosius also nominated the last pair of pagan consuls in Roman history (Tatianus and Symmachus) in 391.[131] Theodosius allowed pagan practices – that did not involve sacrifice – to be performed publicly and temples to remain open.[92][132][133]

He also voiced his support for the preservation of temple buildings, but failed to prevent damaging several holy sites in the eastern provinces which most scholars believe was sponsored by Cynegius, Theodosius' praetorian prefect.[133][134][135] Some scholars have held Theodosius responsible for his prefect's behavior. Following Cynegius' death in 388, Theodosius replaced him with a moderate pagan who subsequently moved to protect the temples.[136][137][138] There is no evidence of any desire on the part of the emperor to institute a systematic destruction of temples anywhere in the Theodosian Code, and no evidence in the archaeological record that extensive temple destruction took place.[139][140]

While conceding that Theodosius's reign may have been a watershed period in the decline of the old religions, Cameron downplays the emperor's religious legislation as having a limited role.[141] In his 2020 biography of Theodosius, Mark Hebblewhite concludes that Theodosius never saw himself, or advertised himself, as a destroyer of the old cults.[142][115][143]

Theodosius II and Pope Leo I

editBy the early fifth century, the senatorial aristocracy had almost universally converted to Christianity.[144] This Christianized Roman aristocracy was able to maintain, in Italy, up to the end of the sixth century, the secular traditions of the city of Rome.[145] This survival of secular tradition was aided by the imperial government, but also by Pope Leo I. Peter Brown writes that from the very beginning of his pontificate in the Western Empire (440–61), Leo "ensured that the 'Romans of Rome' should have a say in the religious life of the City".[146]

The Western Roman Empire declined during the 5th century, while the Eastern Roman Empire during the reign of Emperor Theodosius II (408–50) was functioning well. Theodosius II enjoyed a strong position at the centre of the imperial system.[147] Decline in the West led both Eastern and Western authorities to assert their right to power and authority over the Western Empire.[148] Theodosius II claim was based on Roman law and military power.[149] Leo responded, using the concept of inherited 'Petrine' authority.[150] The Councils of Ephesus and Chalcedon in 449 and 451, convened by the Eastern emperors Theodosius II (407–450) and Marcianus (450–457), were unacceptable to the papacy. Pope Leo attempted to challenge the imperial decisions taken at these councils.[151] He argued that the emperor should concern himself with 'secular matters', while 'divine matters' had a different quality and should be managed by 'priests' (sacerdotes).[151][152]

Pope Leo was not successful.[151][152] The Roman emperors of the first three centuries had seen the control of religion as one of their functions, taking among their titles pontifex maximus ("chief priest") of the official cults. The Western Christian emperors did not see themselves as priests, surrendering the title pontifex maximus under the emperor Gratian.[153] The Christian Eastern emperors, on the other hand, believed the regulation of religious affairs to be one of their prerogatives.[154] The Western emperor Valentinian III (425–55) was, in essence, appointed by Theodosius, and there is some evidence for Valentinian willingly acquiescing to the East's policies.[155] Without the support of the Western emperor Leo accepted Theodosius' authority over the West, thereby beginning the trend toward state control of the church.[151][152]

Sixth to eighth centuries

editIn 535, Justinian I attempted to assert control of Italy, resulting in the Gothic War which lasted 20 years.[156] Once fighting ceased, the senatorial aristocracy returned to Rome for a period of reconstruction. Changes from the war, and from Justinian's 'adjustments' to Italy's administration in the decades after it, removed the supports that had allowed the aristocracy to retain power. The Senate declined rapidly at the end of the sixth and early seventh century coming to its end sometime before 630 when its building was converted into a church.[157] Bishops stepped into roles of civic leadership in the former senator's places.[156] The position and influence of the pope rose.[158]

Justinian took an active concern in ecclesiastical affairs and this accelerated the trend towards the control of the Church by the State.[154][159] Where Constantine had granted, through the Edict of Milan, the right to all peoples to follow freely whatever religion they wished, the religious policy of Justinian I reflected his conviction that a unified Empire presupposed unity of faith.[160][161] Under emperor Justinian, "the full force of imperial legislation against deviants of all kinds, particularly religious" ones, was applied in practice, writes Judith Herrin, historian of late antiquity.[162] Pierre Chuvin describes the severe legislation of the early Byzantine Empire, as causing the freedom of conscience that had been the major benchmark set by the Edict of Milan to be fully abolished.[163]

Before the 800s, the 'Bishop of Rome' had no special influence over other bishops outside of Rome, and had not yet manifested as the central ecclesiastical power.[164] There were regional versions of Christianity accepted by local clergy that it's probable the papacy would not have approved of – if they had been informed.[164] From the late seventh to the middle of the eighth century, eleven of the thirteen men who held the position of Roman Pope were the sons of families from the East, and before they could be installed, these Popes had to be approved by the head of State, the Byzantine emperor.[165]

The union of church and state buoyed the power and influence of both, but the Byzantine papacy, along with losses to Islam, and corresponding changes within Christianity itself, put an end to Ancient Christianity.[166][167][168] Most scholars agree the 7th and 8th centuries are when the 'end of the ancient world' is most conclusive and well documented.[169][170] Christianity transformed into its medieval forms as exemplified by the creation of the Papal state, and the alliance between the papacy and the militant Frankish king Charlemagne.[171][168]

With the formation of the Papal State, the emperor's properties came into the possession of the bishop of Rome, and that is when conversions of temples into churches truly began in earnest.[172] According to Schuddeboom, "With the sole exception of the Pantheon, all known temple conversions in the city of Rome date from the time of the Papal State".[173] Scholarship has been divided over whether this represents Christianization as a general effort to demolish the pagan past, or was simple pragmatism, or perhaps an attempt to preserve the past's art and architecture, or some combination.[174]

Mathematical modelling

editDemographer John D. Durand describes two types of population estimates: benchmarks derived from data at a given time, and estimates that can be carried forward or backward between such benchmarks.[175] Reliability of each varies based on the quality of the data.[175] Romans were "inveterate census takers," but few of their records remain.[176] Durand says historians have pieced together the fragments of census statistics that still exist "with such historical and archaeological data as reported size of armies, quantities of grain shipments and distributions, areas of cities, and indications of the extent and intensity of cultivation of lands".[176]

Sociologists Rodney Stark and Keith Hopkins have estimated an average compounded annual rate of growth for early Christianity that, in reality, would have varied up and down and region by region.[177][1] Ancient historian Adam Schor writes that "Stark applied formal models to early Christian material... [describing] early Christianity as an organized but open movement, with a distinct social boundary, and a set kernel of doctrine. The result, he argued, was consistent conversion and higher birth rates, leading to exponential growth."[178] Stark states a 3.4% growth rate compounded annually while Keith Hopkins uses what he calls "parametric probability" to reach 3.35%.[177][1]

Art historian Robert Couzin, who specializes in Early Christianity, has studied numbers of Christian sarcophagi in Rome. He has written that "more sophisticated mathematical models (for the shape of the expansion curve) could affect certain assumptions, but not the general tendency of the numerical hypotheses".[179]

Classical scholar Roger S. Bagnall found that, by isolating Christian names of sons and their fathers, he could trace the growth of Christianity in Roman Egypt.[180][181] While Bagnall cautions about extrapolating from his work to the rest of the Roman Empire, Stark writes that a comparison of the critical years 239–315 shows a correlation of 0.86 between Stark's own projections for the overall empire and Bagnall's research on Egypt.[182][180]

Though the reliability of population numbers remains open to question,[176] Garry Runciman, historical sociologist, has written that "It seems agreed by all the standard authorities that during the course of the third century there was a significant rise, unquantifiable as it is bound to be, in the absolute number of Christians".[183]

Possible reasons for a top-down spread

editTraditional conflict models

editAccording to Bagnall, the story of the rise of Christianity has traditionally been told in terms of contest and conflict ending Roman paganism in the late fourth and early fifth centuries.[184][185] Recent scholarship has produced large amounts of data, with modern computer technology providing the ability to analyze it, leading to the view that paganism did not end in the late fourth century.[186][187][188] There are many signs that a healthy paganism continued into the fifth century, and in some places, into the sixth and beyond.[189][190] Archaeology indicates that in most regions the decline of paganism was slow, gradual and untraumatic.[191][192]

Violence and temple destruction

editPeter Brown writes that much of the previous framework for understanding Late Antiquity has been based on the dramatized "tabloid-like" accounts of the destruction of the Serapeum of Alexandria in 391, its supposed connection to the murder of Hypatia, and the application of the Theodosian law code.[193][194] Written historical sources are filled with episodes of conflict, yet events in late antiquity were often dramatized by both pagans and Christians for their own ideological reasons.[195] The language of the Code parallels that of the late fourth and early fifth century Christian apologists in Roman–style rhetoric of conquest and triumph.[196] For many earlier historians, this created the impression of on–going violent conflict between pagans and Christians on an empire-wide scale with the destruction of the Serapeum being only one example of many temples having been destroyed by Christians.[197]

New archaeological research has revealed that the Serapeum was the only temple destroyed in this period in Egypt.[198] Classicist Alan Cameron writes that the Roman temples in Egypt "are among the best preserved in the ancient world".[199] Temple destruction is attested to in 43 cases in the written sources, but only four have been confirmed by archaeological evidence.[200] [note 3] Recent scholarship has become that Hypatia's murder was largely political and probably occurred in 415 not 391.[206][193] There is no evidence that the harsh penalties of the anti-sacrifice laws were ever enforced.[207]

Some of the most influential textual sources on pagan-Christian violence concerns Martin, Bishop of Tours (c. 371–397), the Pannonian ex-soldier who is, as Salzman describes, "solely credited in the historical record as the militant converter of Gaul".[208] The portion of the sources devoted to attacks on pagans is limited, and they all revolve around Martin using his miraculous powers to overturn pagan shrines and idols but not to ever threaten or harm people.[209] Salzman concludes that "None of Martin's interventions led to the deaths of any Gauls, pagan or Christian. Even if one doubts the exact veracity of these incidents, the assertion that Martin preferred non-violent conversion techniques says much about the norms for conversion in Gaul" in 398 when Sulpicius Severus, who knew Martin, wrote Martin's biography.[210]

In a comparative study of levels of violence in Roman society, German ancient historian Martin Zimmermann, concludes there was no increase in the level of violence in the Empire in Late Antiquity.[211][212] Acts of violence had always been an aspect of Roman society, but they were isolated and rare.[213][214][215] Archaeologist David Riggs writes that evidence from North Africa reveals a tolerance of religious pluralism and a vitality of traditional paganism much more than it shows any form of religious violence or coercion: "persuasion, such as the propagation of Christian apologetics, appears to have played a more critical role in the eventual "triumph of Christianity" than was previously assumed".[216][217]

The Oxford Handbook of Late Antiquity says that "Torture and murder were not the inevitable result of the rise of Christianity."[218] There were a few ugly incidents of local violence, but there was also a fluidity in the boundaries between the communities and what Salzman describes as "coexistence with a competitive spirit."[219] In most regions of the Empire, pagans were simply ignored. Current evidence indicates "Jewish communities also enjoyed a century of stable, even privileged, existence" says Brown.[220] Jan N. Bremmer has written that recent evidence shows "religious violence in Late Antiquity is mostly restricted to violent rhetoric: 'in Antiquity, not all religious violence was that religious, and not all religious violence was that violent'."[221]

As a result, the conflict model has become marginalized in the twenty first century.[5] According to historian Raymond Van Dam, "an approach which emphasizes conflict flounders as a means for explaining both the initial attractions of a new cult like Christianity, as well as, more importantly, its persistence".[222] Archaeologists Luke Lavan and Michael Mulryan of the Centre for Late Antique Archaeology indicate that archaeology does not show evidence of widespread conflict.[223] Historian Michelle Renee Salzman writes that, in light of current scholarship, violence can not be seen as a central factor in explaining the spread of Christianity in the western empire.[224][225]

Socio-economic factors

editSome innate characteristics of Roman Empire contributed to Christianization: travel was made easier by universal currency, laws, relative internal security and the good roads of the empire. Religious syncretism, Roman political culture, a common language, and Hellenist philosophy made Christianization easier than in places like Persia or China.[226] Judaism was also important to the spread of Christianity; evidence clearly shows the Diaspora communities were where Christians gave many of their earliest sermons.[227]

The fourth century developed new forms of status and wealth that included moving away from the old silver standard.[228] Brown says Constantine consolidated loyalty at the top through his spectacular generosity, paying his army and his high officials in gold and thereby flooding the economy with gold.[229] The imperial bureaucracy soon began demanding that taxes also be paid in gold.[230] This created multiple problems.[231]

"The fourth century scramble for gold ensured that the rural population was driven" hard says Brown.[232] Eighty percent of the population provided the labor to harvest 60% of the empire's wealth, most of which was garnered by the wealthy.[233] This contributed to unrest.[234] Constantine reached out to the provincial elite for help with unrest and other problems, enlarging the Senate's membership from about 600 to over 2,000.[235] This also contributed to unrest and change as the novi homines ("new men", first in their family to serve in the Roman Senate) were more willing to accept religious change.[236] In response to all of this, bishops became intercessors in society, lobbying the powerful to practice Christian benevolence.[237] After 370/380, wealth and cultural prestige began moving toward the Catholics.[238]

Influence of legislation

editIn 429, Emperor Theodosius II (r. 402 – 450) ordered that all of the laws, from the reign of Constantine up to himself and Valentinian III, be found and codified.[239] For the next nine years, twenty-two scholars, working in two teams, dug through archives and assembled, edited and amended empirical law into 16 books containing more than 2,500 constitutions issued between 313 and 437. It was published as the Theodosian Code in 438.[240][241] The code covers political, socioeconomic, and cultural subjects with religious laws in Book 16.[242]

Constantine and his descendants used law to grant "imperial patronage, legal rights to hold property, and financial assistance" to the church, thereby making important contributions to its success over the next hundred years.[243][244] Laws that favored Christianity increased the church's status which was all important for the elites.[245][246] Constantine had tremendous personal popularity and support, even amongst the pagan aristocrats, prompting some individuals to become informed about their emperor's religion.[247] This passed along through aristocratic kinship and friendship networks and patronage ties.[248] Emperors who modeled Christianity's moral appeal with aristocratic honor, combined with laws that made Christianity attractive to the aristocratic class, led to the conversion of the aristocracy beginning in the 360s under Gratian.[249][250]

The Imperial laws collected in Chapter 10, Book XVI of the Theodosian Code provide important evidence of the intent of Christian emperors to promote Christianity, eliminate the practice of sacrifice and control magic. While it is difficult to date with any confidence any of the laws in the Code to the time of Constantine a century earlier,[251][252][253] most scholars agree that Constantine issued the first law banning paganism's public practice of animal sacrifice.[254][255] Blood sacrifice of animals (or people) was the element of pagan culture most abhorrent to Christians, though Christian emperors often tolerated other pagan practices.[256] Brown notes that the language of the anti-sacrifice laws "was uniformly vehement", and the "penalties they proposed were frequently horrifying", evidencing the intent of "terrorizing" the populace into accepting the absence of public sacrifice being imposed by law.[257]

However, the Code does not have the ability to tell how, or if, these policies were actually carried out.[258][259] There is no record of anyone in Constantine's era being executed for sacrificing, nor is there evidence of any of the horrific punishments ever being enacted.[260][261] Imperial commands provided magistrates with a license to act, but those magistrates chose how, or whether to act, for themselves, according to local circumstances. Legal anthropologist Caroline Humfress says the idea of "an empire-wide 'legal system' being imposed from above" before Justinian does not accurately reflect the social and legal realities of the earlier centuries of the Roman Empire.[4] Humfress writes that Roman imperial law, though not irrelevant, was not a determining factor in Roman society before the sixth century.[4]

Sacrifices continued to be performed privately, in the home, and in the country away from the imperial court, but the public ritual killing of animals seems to have largely disappeared from civic festivals by the time of Julian (361 to 363). Evidence for public sacrifices in Constantinople and Antioch altogether runs out by the end of the fourth century.[125][126] Bradbury states that the complete disappearance of public sacrifice "in many towns and cities must be attributed to the atmosphere created by imperial and episcopal hostility".[262]

Paganism in a broader sense did not end when public sacrifice did.[263] Brown says polytheists were accustomed to offering prayers to the gods in many ways and places that did not include sacrifice: at healing springs, in caves, in deep woods, with lights, dancing, feasting and clouds of incense. "Pollution" was only associated with sacrifice, and the ban on sacrifice had fixed boundaries and limits.[264] The end of sacrifice led to the birth of new pagan practices such as adding Neoplatonic theurgy to philosophical practices like stoicism.[265] Pagan religions also directly transformed themselves over the next two centuries by adopting some Christian practices and ideas.[266] Paganism thereby continued up through the sixth century with still existing centers of paganism in Athens, Gaza, Alexandria, and elsewhere.[263]

Possible reasons for a grassroots spread

editThis approach sees the cultural and religious change of the early Roman Empire as the cumulative result of multiple individual behaviors.[267] When one person learned what constituted Christian self-identification from another person, adopting and imitating that for themselves, the societal transformation called "Christianization" emerged naturally.[6]

Peter Brown writes that the emergence of ethical monotheism in a polytheistic world was the single most crucial change made in a Late Antique culture experiencing many changes.[268] The content of Christianity was at the center of this age, Brown adds, contributing to both a "behavioral revolution" and a "cognitive revolution" which then changed the "moral texture of the late Roman world".[269][270][271]

A minority has argued that moral differences between pagans and Christians were not real differences. For example, Ramsay MacMullen has written that any real moral differences would need to be observable in Roman society at large, and he says there were none that were, offering as examples Christian failure to make any observable impact on the practice of slavery, increasingly cruel judicial penalties, corruption and the gladiatorial shows.[272]

Runciman writes that recent research has shown it was the formal unconditional altruism of early Christianity that accounted for much of its early success.[273] Sociologist E. A. Judge cites the powerful combination of new ideas, and the social impact of the church together creating the central pivotal point for the religious conversion of Rome.[7][8]

New ideas

editInclusivity and exclusivity

editAncient Christianity was unhindered by either ethnic or geographical ties; it was open to being experienced as a new start, for both men and women, rich and poor; baptism was free, there were no fees, and it was intellectually egalitarian, making philosophy and ethics available to ordinary people who might not even have known how to read.[274] Many scholars see this inclusivity as the primary reason for Christianity's success.[275]

Historian Raymond Van Dam says conversion produced a new way of thinking and believing that involved "a fundamental reorganization in the ways people thought about themselves and others".[222] Christianity embraced all, including "sinners"; the term for sinner (Ancient Greek: αμαρτωλοί), meaning the immoral, is a Greek term for those 'on the outside'. Its use was undermined by Jesus. Jesus did not classify everyone as sinners, but he did call for those who considered themselves insiders to repent. Paul extended the term's application to everyone, arguing that everyone is an outsider who can become an insider.[276]

A key characteristic of these inclusive communities was their unique type of exclusivity which used belief to construct identity and social boundaries.[277] Believing was the crucial and defining characteristic of membership; it set a "high boundary" that strongly excluded the "unbeliever". Bible scholar Paul Raymond Trebilco says that these high boundaries were set without social distancing or vilification of the outsiders themselves, since context reveals "a clear openness to these 'outsiders' and a strong 'other regard' for them".[278] Strong boundaries for insiders, and openness to outsiders as possible converts, are both held in very real tension in New Testament and early patristic writings.[279] However, the early Christian had exacting moral standards that included avoiding contact with those that were seen as still "in bondage to the Evil One": (2 Corinthians 6:1–18; 1 John 2: 15–18; Revelation 18: 4; II Clement 6; Epistle of Barnabas, 1920).[280] According to Philosopher and philologist Danny Praet, the exclusivity of Christian monotheism formed an important part of its success enabling it to maintain its independence in a society that syncretized religion.[281] He adds that this gave Christianity the powerful psychological attraction of elitism.[282]

Kerygma (central message)

editAccording to Greek scholar Matthew R. Malcolm, central to the kerygma is the concept that the power of God is manifested through Jesus in a reversal of power.[283] In the gospel of Matthew (20:25–26) Jesus is quoted as saying: "You know that the rulers of the Gentiles lord it over them, and their high officials exercise authority over them. Not so with you. Instead, whoever wants to become great among you must be a servant..." Biblical scholar Wayne Meeks has written that: "the ultimate power and structure of the universe" [God] has manifested itself in human society through Jesus' act of giving up his power for the sake of love. This reversal has impact on all aspects of the message: it redefines love as an "other-regarding sacrificial act",[284] and it redefines the nature and practice of power and authority as service to others.[283] Meeks concludes "this must have had a very powerful, emotional appeal to people".[284]

This included a "conscious dismantling of [Roman] concepts of hierarchy and power".[285][286] From the beginning, the Pauline communities cut across the social ranks. Paul's understanding of the innate paradox of an all powerful Christ dying as a powerless man created a new social order unprecedented in classical society.[287] New Testament scholar N. T. Wright argues that these ideas were revolutionary to the classical world.[288]

This message contained the assertion that Christian salvation was made available to all, and it included eternal life, but not for the unbeliever. Ancient paganism had a variety of views of an afterlife from a belief in Hades to a denial of eternal life completely.[289] Afterlife punishments can be found in other religions preceding Christianity. One scholar has concluded "Hell is a Greek invention".[290] Praet says that much of the Roman population no longer believed in Graeco–Roman afterlife punishments, so there is no reason to expect they would take the Christian version more seriously.[290] While it may or may not have been a major cause of conversion, writings from the Christians Justin and Tatian, the pagan Celsus, and the Passio of Ptolemaeus and Lucius are just some of the sources that confirm Christians did use the doctrine of eternal punishment, and that it did persuade some non-believers to convert.[282]

The Christian teaching of bodily resurrection was new, (and not readily accepted), but most Christian views of an afterlife were not new. What they had was the novelty of exclusivity: right belief became as significant a determiner of the future as right behavior.[291] Ancient Christians backed this up with prophecies from ages old documents and living witnesses, giving Christianity its claim to a historical base. This was new and different from paganism.[292] Praet writes that anti-Christian polemics of the era never questioned that: "[Jesus'] birth, teachings, death and resurrection took place in the reigns of the emperors Augustus and Tiberius, and until the end of the first century, the ancient church could produce living witnesses who claimed to have seen or spoken to the Savior".[292] Many modern scholars have seen this historical base as one of the major reasons for Christianity's success.[292]

Social practices

editWomen

editIt has, for many years, been one of the axioms of scholars of early Christianity that significant numbers of women composed its earliest members.[293] Theologian and historian Judith Lieu writes that the presence of large numbers of female converts within Christianity is not statistically documented.[294] Pagan writers wrote polemics criticizing the attraction of women to Christianity along with the uneducated masses, children, and "thieves, burglars and poisoners", but Lieu describes this as politically motivated rhetoric that cannot be depended upon to prove the presence of large numbers of women.[295] Lieu also notes that, "No Christian source explicitly celebrates the number of women joining their ranks".[296]

Art historian Janet Tulloch says that "Unlike the early Christian literary tradition, in which women are largely invisible, misrepresented, or omitted entirely, female figures in early Christian art play significant roles in the transmission of the faith".[297] Feminist theologian Elisabeth Schüssler Fiorenza wrote in her seminal work In Memory of Her: a Feminist Theological Reconstruction of Christian Origins that many of Jesus' followers were women.[298] The Pauline epistles in the New Testament provide some of the earliest documentary sources of women as true missionary partners in expanding the Jesus movement.[299][300]

In the church rolls from the second century, there is conclusive evidence of groups of women "exercising the office of widow".[301][302] Historian Geoffrey Nathan says that "a widow in Roman society who had lost her husband and did not have money of her own was at the very bottom of the social ladder".[303] The church provided practical support to those who would, otherwise, have been in destitute circumstances, and this "was in all likelihood an important factor in winning new female members".[301][304]

Professor of religious studies at Brown University, Ross Kraemer, argues that Christianity offered women of this period a new sense of worth.[305] Lieu affirms that women of note were attracted to Christianity as evidenced in the Acts of the Apostles, where mention is made of Lydia, the seller of purple at Philippi, and of other noble women at Thessalonica, Berea and Athens ( 17.4, 12, 33–34).[306] Lieu writes that, "In parts of the Empire, influential women were able to use religion to negotiate a role for themselves in society that existing conceptual frameworks did not legitimate".[307] As classics scholar Moses Finley writes, "there is no mistaking the fact that Homer fully reveals what remained true for the whole of antiquity: that women were held to be naturally inferior."[308]

There is some evidence of disruption of traditional women's roles in some of the mystery cults, such as Cybele, but there is no evidence this went beyond the internal practices of the religion itself. The mysteries created no alternative in larger society to the established patterns.[309] There is no evidence of any effort in Second Temple Judaism to harmonize the roles or standing of women with that of men.[310] Roman Empire was an age of awareness of the differences between male and female. Social roles were not taken for granted. They were debated, and this was often done with some misogyny.[311] Paul uses a basic formula of reunification of opposites, (Galatians 3:28; 1 Corinthians 12:13; Colossians 3:11) to simply wipe away such social distinctions. In speaking of slave/free, male/female, Greek/Jew, circumcised/uncircumcised, and so on, he states that "all" are "one in Christ" or that "Christ is all". This became part of the message of the early church and the practice of the Pauline communities.[311]

Having their female (and imperfect male) babies taken from them and exposed, was an accepted fact of Roman life for most women.[312] In 1968, J. Lindsay reported that even in large families "more than one daughter was practically never reared."[313][314] There was also a high mortality rate among women due to childbirth and abortion.[315] Elizabeth Castelli writes: "The ascetic life, especially the monastic life, may have provided women with a mode of escape from the rigors and dangers of married and maternal existence, with the prospect of an education and (in some cases) an intellectual life, and with access to social and economic power that would otherwise have eluded them".[316][317]

Judith Lieu cautions that there is "good reason for rejecting a model that understands women's attraction to early Christianity... purely in terms of 'what it did for them'."[318] A survey of the literature of the early period shows female converts as having one thing in common: that of being in danger. Women took real risks to spread the gospel.[319] Ordinary women moved in and out of houses and shops and marketplaces, took the risk of speaking out and leading people, including children, outside the bounds of the "proper authorities". This is evident in the sanctions and labels their antagonists used against them.[320] Power resided with the male authority figure, and he had the right to label any uncooperative female in his household as insane or possessed, to exile her from her home, and condemn her to prostitution.[321] Kraemer theorizes that "Against such vehement opposition, the language of the ascetic forms of Christianity must have provided a strong set of validating mechanisms", attracting large numbers of women.[322][323]

Sexual morality

editBoth the ancient Greeks and the Romans cared and wrote about sexual morality within categories of good and bad, pure and defiled, and ideal and transgression.[324] These ethical structures were built on the Roman understanding of social status. Slaves were not thought to have an interior ethical life because they had no status; they could go no lower socially. They were commonly used sexually, while the free and well-born who used them were thought to embody social honor and the ability to exhibit the fine sense of shame and sexual modesty suited to their station.[325] Sexual modesty meant something different for men than it did for women, and for the well-born, than it did for the poor, and for the free citizen, than it did for the slave — for whom the concepts of honor, shame and sexual modesty were said to have no meaning at all.[325]

In the ancient Roman Empire, "shame" was a profoundly social concept that was always mediated by gender and status. "It was not enough that a wife merely regulate her sexual behavior in the accepted ways; it was required that her virtue in this area be conspicuous."[326] Men, on the other hand, were allowed sexual freedoms such as live-in mistresses and sex with slaves.[327] This duality permitted Roman society to find both a husband's control of a wife's sexual behavior a matter of intense importance, and at the same time see that same husband's sex with young slave boys as of little concern.[328]

The Greeks and Romans said humanity's deepest moralities depended upon social position which was given by fate; Christians advocated the "radical notion of individual freedom centered around ... complete sexual agency".[329] Paul the Apostle and his followers taught that "the body was a consecrated space, a point of mediation between the individual and the divine".[330] This meant the ethical obligation for sexual self-control was to God, and it was placed on each individual, male and female, slave and free, equally, in all communities, regardless of status. It was "a revolution in the rules of behavior, but also in the very image of the human being".[331] In the Pauline epistles, porneia was a single name for the array of sexual behaviors outside marital intercourse. This became a defining concept of sexual morality.[330] Such a shift in definition utterly transformed "the deep logic of sexual morality".[332]

Care for the poor

editProfessor of religion Steven C. Muir has written that "Charity was, in effect, an institutionalized policy of Christianity from its beginning. ... While this situation was not the sole reason for the group's growth, it was a significant factor".[333] Christians showed the poor great generosity, and "there is no disputing that Christian charity was an ideology put into practice".[334][note 4] Prior to Christianity, the wealthy elite of Rome mostly donated to civic programs designed to elevate their status, though personal acts of kindness to the poor were not unheard of.[336][337][338] Salzman writes that the Roman practice of civic euergetism ("philanthropy publicly directed toward one's city or fellow citizens") influenced Christian charity "even as they remained distinct components of justifications for the feeding of Rome well into the late sixth century".[339][note 5]

Health care

editTwo devastating epidemics, the Antonine Plague in 154 and the Plague of Cyprian in 251, killed a large number of the empire's population, though there is some debate over how many.[345] Graeco-Roman doctors tended largely to the elite, while the poor mostly had recourse to "miracles and magic" at religious temples.[346] Christians, on the other hand, tended to the sick and dying, as well as the aged, orphaned, exiled and widowed.[347][348] Many of these caretakers were monks and nuns. Christian monasticism had emerged toward the end of the third century, and their numbers grew such that, "by the fifth century, monasticism had become a dominant force impacting all areas of society".[349][350]

The monastic health care system was innovative in its methods, allowing the sick to remain within the monastery as a special class afforded special benefits and care. This destigmatized illness and legitimized the deviance from the norm that sickness includes. This formed the basis for future public health care.[351] According to Albert Jonsen, a historian of medicine, "the second great sweep of medical history [began] at the end of the fourth century, with the founding of the first Christian hospital for the poor at Caesarea in Cappadocia."[352][353][note 6] By the fifth century, the founding of hospitals for the poor had become common for bishops, abbots and abbesses.[356] Koester argues that the success of Christianity is not simply in its message; "one has to see it also in the consistent and very well thought out establishment of institutions to serve the needs of the community".[357]

Community

editAccording to Stark, "Christianity did not grow because of miracle working in the marketplaces ... or because Constantine said it should, or even because the martyrs gave it such credibility. It grew because Christians constituted an intense community" which provided a unique "sense of belonging".[358][359] Praet has written that, "in his very influential booklet Pagans and Christians in an Age of Anxiety, E. R. Dodds acknowledged ... 'Christians were in a more than formal sense 'members one of another': [Dodds thinks] that was a major cause, perhaps the strongest single cause, of the spread of Christianity".[359]

Christian community was not just one thing. Experience and expression were diverse. Yet early Christian communities did have commonalities in the kerygma (the message), the rites of baptism and the eucharist.[360] As far back as it can be traced, evidence indicates the rite of initiation into Christianity was always baptism.[361] In Christianity's earliest communities, candidates for baptism were introduced by a teacher or other person willing to stand surety for their character and conduct. Baptism created a set of responsibilities within each Christian community, which some authors described in quite specific terms.[362] Candidates for baptism were instructed in the major tenets of the faith (the kerygma), examined for moral living, sat separately in worship, could not receive the eucharist, and were generally expected to demonstrate commitment to the community and obedience to Christ's commands before being accepted into the community as a full member.[363]

Celebration of the eucharist was the common unifier for Christian communities, and early Christians believed the kerygma, the eucharist and baptism came directly from Jesus of Nazareth.[361] According to Dodds, "A Christian congregation was from the first a community in a much fuller sense than any corresponding group of Isis followers or Mithras devotees. Its members were bound together not only by common rites but by a common way of life".[364]

According to New Testament professor Joseph Hellerman, New Testament writers choose 'family' as the central social metaphor to describe their community, and by doing so, they redefined the concept of family.[365] In both Jewish and Roman tradition, genetic families were generally buried together, but an important cultural shift took place in the way Christians buried one another: they gathered unrelated Christians into a common burial space, as if they really were one family, "commemorated them with homogeneous memorials and expanded the commemorative audience to the entire local community of coreligionists".[366] The Jewish ethic and its concept of community as family is what made "Christianity's power of attraction ... not purely religious but also social and philosophical".[367] The Christian church was modeled on the synagogue. Christian philosophers synthesized their own views with Semitic monotheism and Greek thought. The Old Testament gave the new religion of Christianity roots reaching back to antiquity. In a society which equated dignity and truth with tradition, this was significant.[367]

Community on a larger scale is evidenced by a study of 'letters of recommendation' that Christians created to be taken by a traveler from one group of believers to another.[368][369] Security and hospitality when traveling had traditionally been undependable for most, being ensured only by, and for, those with the wealth and power to afford them. By the late third and early fourth centuries, Christians had developed a 'form letter' of recommendation, only requiring the addition of an individual's name, that extended trust and welcome and safety to the whole household of faith, "though they were strangers".[368] Sociologist E. A. Judge writes of the fourth century diary of Egeria which documents her travels throughout the Middle East, seeing the old sites of the Biblical period, the monks, and even climbing Mount Sinai: "At every point she was met and looked after". The same benefits were applied to others carrying a Christian letter of recommendation as members of the community.[368]

Martyrdom

editThe Roman government practiced systematic persecution of Christian leaders and their property in 250–51 under Decius, in 257–60 under Valerian, and expanded it after 303 under Diocletian. While it is understood by scholars that persecution did cause some apostasy and temporary setbacks in the numbers of Christians, the long term impact on Christian conversion was not negative. Peter Brown writes that "The failure of the Great Persecution of Diocletian was regarded as a confirmation of a long process of religious self-assertion against the conformism of a pagan empire."[370] Persecution and suffering were seen by many at the time of these events, as well as by later generations of believers, as legitimizing the standing of the individual believers that died as well as legitimizing the ideology and authority of the church itself.[371] Drake quotes Robert Markus: "The martyrs were, after the Apostles, the supreme representatives of the community of the faithful in God's presence. In them the communion of saints was most tangibly epitomized".[372]

The result of this was summed up in the second century by Justin Martyr: "it is plain that, though beheaded and crucified, and thrown to wild beasts, and chains, and fire, and all other kinds of torture, we do not give up our confession [of Christ]; but the more such things happen, the more do others and in larger numbers become faithful, and worshippers of God through the name of Jesus".[373] Keith Hopkins concludes that in the third century "in spite of temporary losses, Christianity grew fastest in absolute terms. In other words, in terms of number, persecution was good for Christianity".[374]

Miracles

editIn the minority view, miracles and exorcisms form the most important (and possibly the only) reason for conversion to Christianity in the pre-Constantinian age.[375] These events provide some of the best documented ancient conversions.[376] However, there is a drop-off in the records of miracles in the crucial second and third centuries. Praet writes that "as early as the beginning of the third century, Christian authors admit that the "Golden Age" of miracles is over".[375]

Yet, Christianity grew most rapidly at the end of that same third century indicating that the real impact of miracles in garnering new converts is questionable. In Praet's view, even if Christianity had "retained its miraculous powers", the impact of miracles on conversion would still be questionable, since pagans also produced miracles, and no one questioned that those miracles were as real as Christianity's.[377]

Alternative approaches

editNetwork theory

editClassical archaeologist and ancient historian Anna Collar chooses network theory for explaining Christianization of the Roman Empire, saying: "it does not address why such changes take place, but it can help explain how change happened".[378] Current studies in sociology and anthropology have shown that Christianity in its early centuries spread through its acquisition by one person from another by forming a distinct social network.[379] Collar says that archaeological remains demonstrate that networks are formed wherever there are connections.[380] When groups of people with different ways of life connect, interact, and exchange ideas and practices, "cultural diffusion" occurs. The more groups interact, the more cultural diffusion takes place.[381] Diffusion is the primary method by which societies change; (it is distinct from colonialization which forces elements of a foreign culture into a society).[382]

To understand patterns of development, social network theory treats society as a web of overlapping relationships and ties early Christian growth to its preexisting relationships.[382] Adam M. Schor, a scholar of ancient Mediterranean history, discusses this: "Network theory aided Stark's research (with William Bainbridge) including the ground-breaking conclusion that almost all converts to modern religious groups have friendships or familial bonds with existing members. In fact, Stark used the network concept to back up his projections, positing that Christianity first grew along existing Jewish networks and existing links between Roman cities".[382] Historian Paula Fredriksen says that it is "because of Diaspora Judaism, which is extremely well established [in the imperial age], that Christianity itself, as a new and constantly improvising form of Judaism, is able to spread as it does through the Roman world".[383]

The kind of network formed by early Christian groups is what sociology calls a "modular scale-free network". This is a series of small "cells" that are associations of small groups of people, such as the early home churches in Ephesus and Caesaria, with popular leaders, (such as the Apostle Paul), who are the ones who hold together an otherwise unconnected small cluster of cells.[79]

Network theory says that modular scale free networks are "robust": "they grow without central direction, but also survive most attempts to wipe them out." The third century saw the empire's greatest persecution of Christians while also being the critical century of church growth.[384] Schor adds that "Persecutions (like Valerian's) might have thinned the Christian leadership without damaging the network's long-term growth capacity."[79] Keith Hopkins attests that rapid growth in absolute numbers occurred only in the third and fourth centuries.[385]

Psychology

editPsychological explanations of Christianization are most often based on a belief that paganism declined during the imperial period causing an era of insecurity and anxiety.[386][387] These anxious individuals were seen as the ones who sought refuge in religious communities which offered socialization.[388] For most modern scholars, this view can no longer be maintained since traditional religion did not decline in this period, but remained into the sixth and seventh centuries, and there is no evidence of increased anxiety.[389][390] Psychologist Pascal Boyer says a cognitive approach can account for the transmission of religious ideas and describe the processes whereby individuals acquire and transmit certain ideas and practices, but cognitive theory may not be sufficient to account for the social dynamics of religious movements, or the historical development of religious doctrines, which are not directly within its scope.[391]

Evolution

editThis is grounded in a Neo-Darwinian theory of cultural selection.[392] Empirical evidence indicates behaviors spread because people have a strong tendency to imitate their neighbors when they believe those neighbors are more successful. Anthropologists Robert Boyd and Peter J. Richerson write that Romans believed the early Christian community offered a better quality of life than the ordinary life available to most in the Roman Empire.[393] Runciman writes of Christian altruism attracting pagans, yet also exposing the Christian groups to exploitation. It was care for the sick that primarily contributed to the spread of Christianity according to this view.[394] Care-taking was particularly important during the severe epidemics of the Imperial period when some cities devolved into anarchy. Pagan society had weak traditions of mutual aid, whereas the Christian community had norms that created "a miniature welfare state in an empire which for the most part lacked social services".[393] In Christian communities, care of the sick reduced mortality by, possibly, as much as two-thirds. Extant Christian and pagan sources indicate many conversions were the result of "the appeal of such aid".[393] According to Runciman, a distinctly Christian phenotype of strong reciprocity and unconditional benevolence produced the growth of Christianity.[392]

Diffusion of innovation

editThis view combines an understanding of Christian ideology, and the utility of religion, with analysis of social networks and their environment. It focuses on the power of social interactions and how social groups communicate. In this theory, an innovation's success or failure is dependent upon the characteristics of the innovation itself, the adopters, what communication channels are used, time, and the social system in which it all happens.[381][395] Ideology is always an aspect of religious innovation, but societal change is driven by the social networks formed by the people who follow the new religious innovation.[396]

Religions adapt, adjust and change all the time, therefore a true religious innovation must be seen as a significant change – such as the shift from polytheism to monotheism – on a large scale.[397] Collar argues that even though "the philosophical argument for one god was well known amongst the intellectual elite, ... monotheism can be called a religious innovation within the milieu of Imperial polytheism."[398]

Having quickly begun moving outward from Jerusalem, all the largest cities in the empire had Christian congregations by the end of the first century.[399] These became "hubs" for communicating the ongoing spread of the innovation. The variance in the times of when people responded creates a normal distribution curve. Collar writes, "there is a point on the curve that represents the crux of the diffusion process: the 'tipping point'.[400] This 'tipping' takes place between 10 percent adoption and 20 percent adoption.[401] Christianity achieved this tipping point between 150 and 250 when it moved from less than 50,000 adherents to over a million.[88] This provided enough adopters for it to be self-sustaining and create further growth.[88][90][402]

Effects

editJudicial penalties and clemency

editIn 1986, Ramsay MacMullen wrote "What Difference did Christianity Make?" looking at the consequences of conversion rather than its causes. He has written that "Christianity made no difference";[403] or that it made a negative difference,[404] saying that under the Christian emperors, judicial cruelty rose.[405] MacMullen attributes this to Christian zeal and a belief in purgatory.[406] On the one hand, this is problematic since, "Until the end of the twelfth century the noun purgatorium did not exist; the Purgatory had not yet been born" according to historian Jacques Le Goff.[407] On the other hand, it is possible to identify a mounting severity in imperial criminal law.[408] Classicist Peter Garnsey says this change takes place throughout the entire imperial period beginning under Augustus in the first century. Garnsey writes that increasing severity was the result of the political shift from a Republic to an autocratic empire.[409]

Historian Jill Harries describes Roman justice as always harsh.[410] It was a common belief of those in the Roman Empire that severity was a deterrent.[411] As an example of this, Harries writes of the SC Silanianum, a particularly harsh law passed in 10 AD.[412] The SC Silanianum was originally aimed at slaves who murdered their masters, but its reach and its harshness grew as time passed.[note 7]

On the one hand, increasingly harsh penalties for an ever enlarging number of capital crimes were published by emperors. On the other hand, emperors also wanted to be seen as generous in offering mercy and clemency.[415] Beginning in the first century under Augustus, the established Roman understanding of clemency (clementia) began a transformation that was completed in the fourth century.[416] Christian writers had embraced the concept of clemency and used it to express the mercy of God demonstrated in salvation, thereby combining the two concepts.[417] The use of clementia to indicate forgiveness of wrongs and a mild merciful temper becomes common for writers of the Later Roman Empire.[418]

Christianity did not grow outside Roman culture, it grew within it, ameliorating some of Rome's harsh justice and also adopting some of it.[419][420] Augustine of Hippo advocated the harsh discipline of heretics that allowed some of the milder forms of physical torture.[421] Augustine also urged the heretical Donatist bishop Donatus to practice Christian mildness when dealing with enemies.[422] Augustine praised Marcellinus, who presided over an Imperial inquiry into the Catholic-Donatist controversy, for having conducted his investigation without using torture which was the norm. Ambrose, bishop of Milan, advised his correspondent Studius, a Christian judge, to show clemency, citing as a model Jesus' treatment of the adulteress.[423] Garnsey has written that "Augustine, Ambrose, and other church leaders of progressive views clearly had a beneficent influence on the administration of the law, [but] it is evident that they did not attempt to promote a movement of penal reform, and did not conceive of such a movement".[419] As Peter Brown has summarized: "When it came to the central functions of the Roman state, even the vivid Ambrose was a lightweight".[424]