In poetic metre, a trochee (/ˈtroʊkiː/) is a metrical foot consisting of a stressed syllable followed by an unstressed one, in qualitative meter, as found in English, and in modern linguistics; or in quantitative meter, as found in Latin and Ancient Greek, a heavy syllable followed by a light one (also described as a long syllable followed by a short one).[1] In this respect, a trochee is the reverse of an iamb. Thus the Latin word íbī, 'there', because of its short-long rhythm, in Latin metrical studies is considered to be an iamb, but since it is stressed on the first syllable, in modern linguistics it is considered to be a trochee.

| Disyllables | |

|---|---|

| ◡ ◡ | pyrrhic, dibrach |

| ◡ – | iamb |

| – ◡ | trochee, choree |

| – – | spondee |

| Trisyllables | |

| ◡ ◡ ◡ | tribrach |

| – ◡ ◡ | dactyl |

| ◡ – ◡ | amphibrach |

| ◡ ◡ – | anapaest, antidactylus |

| ◡ – – | bacchius |

| – ◡ – | cretic, amphimacer |

| – – ◡ | antibacchius |

| – – – | molossus |

| See main article for tetrasyllables. | |

The adjective form is trochaic. The English word trochee is itself trochaic since it is composed of the stressed syllable /ˈtroʊ/ followed by the unstressed syllable /kiː/.

Another name formerly used for a trochee was a choree (/ˈkɔːriː/), or choreus.

Etymology

editTrochee comes from French trochée, adapted from Latin trochaeus, originally from the Greek τροχός, trokhós, 'wheel',[2] from the phrase τροχαῖος πούς, trokhaîos poús, 'running foot';[3] it is connected with the word τρέχω, trékhō, 'I run'. The less-often used word choree comes from χορός, khorós, 'dance'; both convey the "rolling" rhythm of this metrical foot. The phrase was adapted into English in the late 16th century.

There was a well-established ancient tradition that trochaic rhythm is faster than iambic.[4] When used in drama it is often associated with lively situations. One ancient commentator notes that it was named from the metaphor of people running (ἐκ μεταφορᾶς τῶν τρεχόντων) and the Roman metrician Marius Victorinus notes that it was named from its running and speed (dictus a cursu et celeritate).[4]

Examples

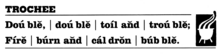

editTrochaic meter is sometimes seen among the works of William Shakespeare:

Double, double, toil and trouble;

Fire burn and cauldron bubble.

Perhaps owing to its simplicity, though, trochaic meter is fairly common in nursery rhymes:

Peter, Peter pumpkin-eater

Had a wife and couldn't keep her.

Trochaic verse is also well known in Latin poetry, especially of the medieval period. Since the stress never falls on the final syllable in Medieval Latin, the language is ideal for trochaic verse. The dies irae of the Requiem mass is an example:

Dies irae, dies illa

Solvet saeclum in favilla

Teste David cum Sibylla.

The Finnish national epic, Kalevala, like much old Finnish poetry, is written in a variation of trochaic tetrameter.

Trochaic metre is popular in Polish and Czech literatures.[6] Vitězslav Nezval's poem Edison is written in trochaic hexameter.[7]

Latin

editIn Greek and Latin, the syllabic structure deals with long and short syllables, rather than accented and unaccented. Trochaic meter was rarely used by the Latin poets in the classical period, except in certain passages of the tragedies and the comedies.[8] The two main metres used in comedy were the trochaic septenarius and trochaic octonarius.

See also

edit- Monometer

- Prosody (Latin)

- Substitution (poetry), Trochaic substitution

- Prosody (Greek)

- Trochaic septenarius

References

edit- ^ Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 27 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 293.

- ^ Etymology of the Latin word trochee[usurped], MyEtymology (retrieved 23 July 2015)

- ^ Trochee, Etymology Online (retrieved 23 July 2015)

- ^ a b A.M. Devine, Laurence Stephens, The Prosody of Greek Speech, p. 116.

- ^ The Complete Works of William Shakespeare. London: Abbey Library/Cresta House, 1977.

- ^ Josef Brukner, Jiří Filip, Poetický slovník, Mladá fronta, Prague 1997, p. 339–340 (in Czech).

- ^ Wiktor J. Darasz, Trochej, Język Polski, 1-2/2001, p. 51 (in Polish).

- ^ Gustavus Fischer, "Prosody", Etymology and an introduction to syntax (Latin Grammar, Volume 1), J. W. Schermerhorn (1876) p. 395.