Changsha[a] is the capital of Hunan, China. It is the 17th most populous city in China with a population of over 10 million,[6] and the third-most populous city in Central China, located in the lower reaches of the Xiang River in northeastern Hunan.

Changsha

长沙市 | |

|---|---|

| Nickname: "星城" (Star City) | |

| Motto(s): "心忧天下,敢为人先" (Care About the World, Dare to Be Pioneers) | |

| |

Location of Changsha City in Hunan | |

| Coordinates (Changsha municipal government): 28°13′41″N 112°56′20″E / 28.228°N 112.939°E | |

| Country | China |

| Province | Hunan |

| Municipal seat | Yuelu District |

| Divisions | 9 County-level divisions, 172 Township divisions |

| Government | |

| • Type | Prefecture-level city |

| • Body | Changsha Municipal People's Congress |

| • CCP Secretary | Wu Guiying |

| • Congress Chairman | Xie Weidong |

| • Mayor | Zhou Haibing |

| • CPPCC Chairman | Wen Shuxun |

| Area | |

| 11,819 km2 (4,563 sq mi) | |

| • Urban | 2,154.1 km2 (831.7 sq mi) |

| • Metro | 3,911.1 km2 (1,510.1 sq mi) |

| Elevation | 63 m (207 ft) |

| Population (2022)[1] | |

| 10,420,600 | |

| • Urban | 5,980,707 |

| • Urban density | 2,800/km2 (7,200/sq mi) |

| • Metro | 10,500,000 |

| • Metro density | 2,700/km2 (7,000/sq mi) |

| • Rank in China | 19th |

| Ethnicity | |

| • Han | 99.22% |

| • Minorities | 0.78% |

| GDP[3] | |

| • Prefecture-level city | CN¥ 1.397 trillion US$ 207.7 billion |

| • Per capita | CN¥ 133,992 US$ 19,925 |

| Time zone | UTC+08:00 (China Standard) |

| Postal code | 410000 |

| Area code | 0731 |

| ISO 3166 code | CN-HN-01 |

| HDI (2016) | 0.817– very high[4] |

| License Plate | 湘A 湘O (police and authorities) |

| City tree | Camphor tree |

| City flower | Azalea |

| Languages | Hunanese(Changsha dialect), Mandarin |

| Website | en |

| Changsha | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

"Changsha" in Simplified (top) and Traditional (bottom) Chinese characters | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 长沙 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 長沙 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Hanyu Pinyin | Chángshā | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Xiang | [tsã13 sɔ33] () | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Literal meaning | "Long Sandbar" | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Former names | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Qing Yang | |||||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 青陽 | ||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 青阳 | ||||||||

| |||||||||

| Lin Xiang | |||||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 臨湘 | ||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 临湘 | ||||||||

| Literal meaning | Overlooking the Xiang | ||||||||

| |||||||||

| Tan Zhou | |||||||||

| Chinese | 潭州 | ||||||||

| Literal meaning | Eddy Prefecture | ||||||||

| |||||||||

The city forms a part of the Greater Changsha Metropolitan Region along with Zhuzhou and Xiangtan, also known as Changzhutan City Cluster. Greater Changsha was named one of the 13 emerging mega-cities in China in 2012 by the Economist Intelligence Unit.[7] It is also a National Comprehensive Transportation Hub,[8] and one of the first National Famous Historical and Cultural Cities in China. Changshanese, a kind of Xiang Chinese, is spoken in the downtown, while Ningxiangnese and Liuyangnese are also spoken in the counties and cities under its jurisdiction.[9] As of the 2020 Chinese census, the prefecture-level city of Changsha had a population of 10,047,914 inhabitants.[10]

Changsha has a history of more than 2,400 years of urban construction,[11] and the name "Changsha" first appeared in the Yi Zhou Shu written in the pre-Qin era.[12] In the Qin dynasty, the Changsha Commandery was set up, and in the Western Han dynasty, the Changsha Kingdom was established. The Tongguan Kiln in Changsha during the Tang dynasty produced the world's earliest underglaze porcelain, which was exported to Western Asia, Africa and Europe.[13] In the period of the Five Dynasties, Changsha was the capital of Southern Chu. In the Northern Song dynasty, the Yuelu Academy (later Hunan University) was one of the four major private academies over the last 1000 years.[14] In the late Qing dynasty, Changsha was one of the four major trade cities for rice and tea in China.[15] In 1904, it was opened to foreign trade, and gradually became a revolutionary city. In Changsha, Tan Sitong established the School of Current Affairs, Huang Xing founded the China Arise Society with the slogan "Expel the Tatar barbarians and revive Zhonghua" (驱除鞑虏,复兴中华), and Mao Zedong also carried out his early political movements here. During the Republican Era, Changsha became one of the major home fronts in the Second Sino-Japanese War, but the subsequent Wenxi Fire in 1938 and the three Battles of Changsha from 1939 to 1942 (1939, 1941 and 1941–42) hit Changsha's economy and urban construction hard.[16]

Changsha is now one of the core cities in the Yangtze River Economic Belt and the Belt and Road Initiative,[17][18] a Beta- (global second-tier) city by the GaWC,[19] a new Chinese first-tier city[20][21] and also a pioneering area for China-Africa economic and trade cooperation.[22] Known as the "Construction machinery capital of the world", Changsha has an industrial chain with construction machinery and new materials as the main industries, complemented by automobiles, electronic information, household appliances, and biomedicine.[23][24] Since the 1990s, Changsha has begun to accelerate economic development, and then achieved the highest growth rate among China's major cities during the 2000s.[25] The Xiangjiang New Area, the first state-level new area in Central China, was established in 2015.[26] As of 2023, more than 180 Global 500 companies have established branches in Changsha.[27] The city has the 27th largest skyline in the world.[28] The HDI of Changsha reached 0.817 (very high) in 2016, which is roughly comparable to a moderately developed country.[29][30]

As of 2023, Changsha hosts 59 institutions of higher education, ranking 8th nationwide among all cities in China.[31] The city houses four Double First-Class Construction universities: Hunan, National University of Defense Technology, Central South, and Hunan Normal, making Changsha the seat of several highly ranked educational institutions.[32][33] It is a major centre of research and innovation in the Asia-Pacific with a high level of scientific research, ranking 23rd globally in 2024.[34] Changsha is the birthplace of super hybrid rice, the Tianhe-1 supercomputer, China's first laser 3D printer,[35] and China's first domestic medium-low speed maglev line.[36] Changsha has been named the first "UNESCO City of Media Arts" in China.[37] The city is home to the Hunan Broadcasting System (HBS), the most influential provincial TV station in China.[38][39]

Names

editChángshā is the pinyin romanization of the Mandarin pronunciation of the Chinese name 長沙 or 长沙, meaning "long sandy place". The name's origin is unknown. It is attested as early as the 11th century BC, when a vassal lord of the area sent King Cheng of Zhou a gift described as a "Changsha softshell turtle" (长沙鳖; 長沙鼈; Chángshā biē). In the 2nd century AD, historian Ying Shao wrote that the Qin use of the name "Changsha" for the area was a continuance of its old name.[40] The name originally described the area. The Chu metropolis was known as Qingyang. The capital of the Kingdom of Changsha—within the present-day city of Changsha—was known as Linxiang, meaning "[place] Overlooking the Xiang River".

History

editThis article needs additional citations for verification. (August 2019) |

Early history

editDevelopment started around 3000 BC when Changsha developed with the proliferation of Longshan culture, although there is no firm evidence of such a link.[clarification needed][41] Evidence exists that people lived and thrived in the area during the Bronze Age. Numerous examples of pottery and other objects have been discovered.

Later Chinese legends related that the Flame and Yellow Emperors visited the area. Sima Qian's history states that the Yellow Emperor granted his eldest son Shaohao the lands of Changsha and its neighbors. During the Spring and Autumn period (8th–5th century BC), the Yue culture spread into the area around Changsha. During the succeeding Warring States period, Chu took control of Changsha. Its capital, Qingyang, became an important southern outpost of the kingdom. In 1951–57 archaeologists explored numerous large and medium-sized Chu tombs from the Warring States Era. More than 3,000 tombs have been discovered. Under the Qin dynasty (221–206 BC), Changsha was a staging post for expeditions south into Guangdong that led to its conquest and the establishment of the Nanyue kingdom.

Under the Han (3rd century BC – 3rd century AD), Linxiang was the capital of the kingdom of Changsha. At first this was a client state held by Liu Bang's Baiyue ally Wu Rui that served as a means of controlling the restive Chu people and as a buffer state against Nanyue. By 202 BC, Linxiang had city walls to protect it against uprisings and invasions. The famous Mawangdui tombs were constructed between 186 and 165 BC. Lady Xin Zhui was buried in the earliest tomb (No. 2) and, during its excavation in the 1970s, was found to have been very well preserved. More importantly, the tombs included the earliest surviving copies of the Tao Te Ching and other important literary and historical documents.

When Wu Rui's descendant Wu Zhu (吳著, Wú Zhù) died childless in 157 BC, the kingdom was granted to a cadet branch of the imperial family as their fief. The kingdom was abolished under Wang Mang's short-lived Xin dynasty and briefly revived by the Eastern Han. In AD 33, its prince was demoted and the area administered as Linxiang County and Changsha Commandery.

The Three Kingdoms state of Wu ruled Changsha for several decades, a period whose administration is well known because its documents have been excavated.[42] Following the turmoil of the Three Kingdoms, Emperor Wu of Jin granted Changsha to his sixth son Sima Yi. The local government had over 100 counties at the beginning of the dynasty. Over the course of the dynasty, the local government of Changsha lost control over a few counties, leaving them to local rule.

The Sui dynasty (6th century) renamed Xiangzhou to Changsha Tan Prefecture or Tanzhou. It was named after Zhaotan in the ninth year of Emperor Kaihuang (589 A.D.) of the Sui dynasty, and the Tanzhou General Manager was established. During the reign of Emperor Yang of the Sui dynasty, Tanzhou was abolished, and Changsha County, a first-level administrative unit, was established, but the jurisdiction area was reduced.[43] Changsha's 3-tier administration was simplified to a 2-tier state and county system, eliminating the middle canton region.[clarification needed] Under the Tang, Changsha prospered as a center of trade between central China and Southeast Asia but suffered during the Anshi Rebellion, when it fell to the rebels.

In early 10th century, Changsha served as the capital of the state of Nanchu (南楚), or Southern Chu, established by Ma Yin (马殷) in 907, one of the ten southern war loads. Nanchu, lasted about 50 years, was the only independent state in the history that has ever been built in Hunan with Changsha as the capital, being eventually overthrown by Nantang (南唐) in 951.

Under the Song dynasty, the Yuelu Academy was founded in 976. It was destroyed by war in 1127 and rebuilt in 1165, during which year the celebrated philosopher Zhu Xi taught there. It was again destroyed by the Mongols during the establishment of the Yuan before being restored in the late 15th century under the Ming. Early 19th-century graduates of the academy formed what one historian called a "network of messianic alumni", including Zeng Guofan, architect of the Tongzhi Restoration,[44] and Cai E, a major leader in the defense of the Republic of China.[45] In 1903 the academy became Hunan High School. Modern-day Hunan University is also a descendant of the Yuelu Academy. Some of its buildings were remodeled from 1981 to 1986 according to their presumed original Song design.

During the Mongol conquest of the Southern Song, Tanzhou was fiercely defended by the local Song troops. After the city finally fell, the defenders committed mass suicide. Under the Ming (14th–17th centuries), Tanzhou was again renamed Changsha and made a superior prefecture.[clarification needed]

Modern history

editUnder the Qing (17th–20th centuries), Changsha was the capital of Hunan and prospered as one of China's chief rice markets. During the Taiping Rebellion, the city was besieged by the rebels in 1852 or 1854[which?] for three months but never fell. The rebels moved on to Wuhan, but Changsha then became the principal base for the government's suppression of the rebellion.

The 1903 Treaty of Shanghai between the Qing and Japanese empires opened the city to foreign trade effective 1904. Most favored nation clauses in other unequal treaties extended the Japanese gains to the Western powers as well. Consequently, international capital entered the town and factories, churches, and schools were built. A college was started by Yale alumni, which later became a medical centre named Xiangya and a secondary school named the Yali School.

Following the Xinhai Revolution, further development followed the opening of the railway to Hankou in Hubei province in 1918, which was later extended to Guangzhou in Guangdong Province in 1936. Although Changsha's population grew, the city remained primarily commercial in character. Before 1937, it had little industry apart from some small cotton-textile, glass, and nonferrous-metal plants and handicraft enterprises.

Mao Zedong, the founder of the People's Republic of China, began his political career in Changsha. He was a student at the Hunan Number 1 Teachers' Training School from 1913 to 1918. He later returned as a teacher and principal from 1920 to 1922. The school was destroyed during the Chinese Civil War but has since been restored. The former office of the Hunan Communist Party Central Committee where Mao Zedong once lived is now a museum that includes Mao's living quarters, photographs and other historical items from the 1920s.

Until May 1927, communist support remained strong in Changsha before the massacre carried out by the right-wing faction of the KMT troops. The faction owed its allegiance to Chiang Kai-shek during its offensive against the KMT's left-wing faction under Wang Jingwei, who was then allied closely with the Communists. The purge of communists and suspected communists was part of Chiang's plans for consolidating his hold over the KMT, weakening Wang's control, and thereby over the entire China. In a period of twenty days, Chiang's forces killed more than ten thousand people in Changsha and its outskirts.

During the Second Sino-Japanese War (1937–45), Changsha's strategic location made it the focus of four campaigns by the Imperial Japanese Army to capture it from the Nationalist Army: these campaigns were the 1st Changsha,[46] the 2nd Changsha, the 3rd Changsha, and the 4th Changsha. The city was able to repulse the first three attacks thanks to Xue Yue's leadership, but ultimately fell into Japanese hands in 1944 for a year until the Japanese were defeated in a counterattack and forced to surrender.[47][48] Before these Japanese campaigns, the city was already virtually destroyed by the 1938 Changsha Fire, a deliberate fire ordered by Kuomintang commanders who mistakenly feared the city was about to fall to the Japanese; Generalissimo Chiang Kai-shek had suggested that the city be burned so that the Japanese force would gain nothing after entering it.[49]

Following the Communist victory in the Chinese Civil War, Changsha slowly recovered from its former damage. Since Deng Xiaoping's Reform and Opening Up Policy, Changsha has rapidly developed since the 1990s, becoming one of the important cities in the central and western regions. At the end of 2007, Changsha, Zhuzhou, and Xiangtan received approval from the State Council for the "Chang-Zhu-Tan (Greater Changsha) Resource-Saving and Environment-Friendly Society Comprehensive Reform Pilot Area", an important engine in the Rise of Central China plan. In 2015, Xiangjiang New Area was approved as a national new area.

Geography

editChangsha is in northeast Hunan Province, the lower reaches of the Xiang River and the western part of the Changliu Basin. It lies between 111°53' to 114°15' east longitude and 27°51' to 28°41' north latitude. The city borders Yichun and Pingxiang of Jiangxi Province in the east, Zhuzhou and Xiangtan in the south, Loudi and Yiyang in the west, and Yueyang and Yiyang in the north. It is about 230 kilometres from east to west and about 88 kilometres from north to south. Changsha covers an area of 11,819 km2 (4,563 sq mi), of which the urban area of 2,150.9 km2 (830.5 sq mi), the urban built-up area is 374.64 km2 (144.65 sq mi). Changsha's highest point is Mount Qixing (七星岭) in Daweishan Town, 1,607.9 m (5,275 ft). The lowest point is Zhanhu (湛湖) in Qiaokou Town, 23.5 m (77 ft).[50]

The Xiang is the main river in the city, running 74 km (46 mi) northward through the territory. 15 tributaries flow into the Xiang, of which the Liuyang, Laodao, Jinjiang and Wei are the four largest.[50] The Xiang divides the city into two parts. The eastern part is mainly commercial and the west is mainly cultural and educational. On 10 October 2001, the seat of Changsha City was transferred from Fanzheng Street to Guanshaling. Since then, the economy of both sides of the Xiang River has achieved a balanced development.[51]

Hydrology

editMost of the rivers in Changsha belong to the Xiang River system. In addition to the Xiangjiang River, 15 tributaries flow into the Xiang, mainly including Liuyang River, Laodao River, Minjiang River, and Qinshui River.[52] 302 tributaries are more than five kilometers long, including 289 in the Xiang River Basin. According to the tributary grading there are 24 primary tributaries, 128 secondary tributaries, 118 third tributaries, and 32 tributaries; and 13 are Zijiang water systems; a fairly complete water system is formed, and the river network is densely distributed. Hydrological characteristics of Changsha: the water system is complete, the river network dense; the water volume greater, the water energy resources abundant; the winter not frozen, and the sediment content small.[53]

Geological characteristics

editThe geological features of Changsha City are: the formation is fully exposed, the granite body is widely distributed, and the geological structure is complex. The strata of each geological and historical period are exposed in Changsha City, and the oldest stratum was formed about one billion years ago. About 600 million years ago, Changsha was a sea, but the sea was not deep. Later, seawater gradually withdrew from the east and west, and most of Liuyang, Changsha, and Wangcheng rose out of the sea and became the northwestern edge of the ancient land of Jiangnan. About 140 million years ago, the sea leaching in the Changsha area ended and it became a land. Due to the influence of crustal movement and geological structure, a long-shaped mountain depression basin, the Chang (Sha) Ping (Jiang) Basin, was formed. Beginning of the new generation, the entire Changping Basin has risen to land. About 3.5 million years ago, the third ice age occurred on the earth, and Liuyang retained the remains of glacier landforms.[53]

Climate

editChangsha has a humid subtropical climate (Köppen Cfa), with annual average temperature being at 17.8 °C (64.0 °F), with a mean of 5.3 °C (41.5 °F) in January and 29.4 °C (84.9 °F) in July. Average annual precipitation is 1,499 millimetres (59.0 in), with a 275-day frost-free period. With a monthly possible-sunshine percentage ranging from 20% in January to 53% in July, the city receives 1,532.8 hours of bright sunshine annually. The four seasons are distinct. The summers are long and very hot, with heavy rainfall, and autumn is comfortable and is the driest season. Winter is chilly and overcast with lighter rainfall more likely than downpours; cold snaps occur with temperatures occasionally dropping below freezing. Spring is especially rainy and humid with the sun shining less than 30% of the time. The minimum temperature ever recorded since 1951 at the current Wangchengpo Weather Observing Station was −12.0 °C (10.4 °F), recorded on 9 February 1972. The maximum was 40.6 °C (105.1 °F) on 13 August 1953 and 2 August 2003 [the unofficial record of 43.0 °C (109.4 °F) was set on 10 August 1934].

| Climate data for Changsha (1991–2020 normals, extremes 1951–present) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 26.9 (80.4) |

30.6 (87.1) |

32.8 (91.0) |

36.1 (97.0) |

36.3 (97.3) |

38.2 (100.8) |

40.4 (104.7) |

40.6 (105.1) |

39.5 (103.1) |

38.5 (101.3) |

33.4 (92.1) |

24.9 (76.8) |

40.6 (105.1) |

| Mean daily maximum °C (°F) | 8.5 (47.3) |

11.5 (52.7) |

15.8 (60.4) |

22.4 (72.3) |

27.1 (80.8) |

30.3 (86.5) |

33.8 (92.8) |

32.7 (90.9) |

28.6 (83.5) |

23.6 (74.5) |

17.7 (63.9) |

11.5 (52.7) |

22.0 (71.5) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 5.1 (41.2) |

7.8 (46.0) |

11.7 (53.1) |

17.9 (64.2) |

22.6 (72.7) |

26.2 (79.2) |

29.6 (85.3) |

28.4 (83.1) |

24.2 (75.6) |

18.9 (66.0) |

13.2 (55.8) |

7.5 (45.5) |

17.8 (64.0) |

| Mean daily minimum °C (°F) | 2.7 (36.9) |

5.2 (41.4) |

8.9 (48.0) |

14.7 (58.5) |

19.3 (66.7) |

23.1 (73.6) |

26.2 (79.2) |

25.4 (77.7) |

21.1 (70.0) |

15.7 (60.3) |

10.0 (50.0) |

4.7 (40.5) |

14.7 (58.6) |

| Record low °C (°F) | −9.5 (14.9) |

−12.0 (10.4) |

−2.3 (27.9) |

1.9 (35.4) |

8.9 (48.0) |

13.1 (55.6) |

19.7 (67.5) |

16.7 (62.1) |

11.8 (53.2) |

2.4 (36.3) |

−2.8 (27.0) |

−10.3 (13.5) |

−12.0 (10.4) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 74.5 (2.93) |

85.0 (3.35) |

149.2 (5.87) |

173.1 (6.81) |

201.7 (7.94) |

224.3 (8.83) |

162.8 (6.41) |

107.5 (4.23) |

86.6 (3.41) |

60.5 (2.38) |

77.7 (3.06) |

53.5 (2.11) |

1,456.4 (57.33) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 0.1 mm) | 13.4 | 13.9 | 17.4 | 16.4 | 15.9 | 14.4 | 10.4 | 10.8 | 8.8 | 9.7 | 9.8 | 10.8 | 151.7 |

| Average snowy days | 4.9 | 2.9 | 0.4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.1 | 1.9 | 10.2 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 79 | 79 | 79 | 78 | 78 | 80 | 74 | 76 | 78 | 77 | 77 | 75 | 78 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 64.7 | 66.5 | 83.5 | 110.0 | 137.1 | 141.4 | 226.7 | 208.5 | 151.2 | 134.0 | 112.4 | 96.8 | 1,532.8 |

| Percent possible sunshine | 20 | 21 | 22 | 28 | 33 | 34 | 54 | 52 | 41 | 38 | 35 | 30 | 34 |

| Source 1: China Meteorological Administration[54][55][56] | |||||||||||||

| Source 2: NOAA[57] | |||||||||||||

Administration

editThe municipality of Changsha exercises jurisdiction over six districts, one county and two county-level cities:

| Map | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Subdivision | Simplified Chinese | Pinyin | Pop.

(2010 census) |

Area (km2) | Dens. (/km2) |

| City Proper | |||||

| Furong District | 芙蓉区 | Fúróng Qū | 523,730 | 42 | 12,470 |

| Tianxin District | 天心区 | Tiānxīn Qū | 475,663 | 74 | 6,428 |

| Yuelu District | 岳麓区 | Yuèlù Qū | 801,861 | 552 | 1,453 |

| Kaifu District | 开福区 | Kāifú Qū | 567,373 | 187 | 3,034 |

| Yuhua District | 雨花区 | Yǔhuā Qū | 725,353 | 114 | 6,363 |

| Wangcheng District | 望城区 | Wàngchéng Qū | 523,489 | 970 | 540 |

| Suburban and rural | |||||

| Liuyang City | 浏阳市 | Liúyáng Shì | 1,278,928 | 4,999 | 256 |

| Ningxiang City | 宁乡市 | Níngxiāng Shì | 1,168,056 | 2,906 | 402 |

| Changsha County | 长沙县 | Chángshā Xiàn | 979,665 | 1,997 | 491 |

Government

editThe current CPC Party Secretary of Changsha is Wu Guiying and the current mayor is Zheng Jianxin.

Economy

editChangsha is one of China's 15 most "developed and economically advanced" cities.[58][20][59] The city's GDP per capita exceeded $20,000 in nominal ($30,000 in PPP) in 2021, which is considered a high-income status by the World Bank and a primary developed city according to the international standard.[30][60] The HDI of Changsha reached 0.817 (very high) in 2016, which is roughly comparable to a moderately developed country.[29][30] Changsha is now one of the core cities in the South Central China region, the Yangtze River Economic Belt and the Belt and Road Initiative,[17][18] a Beta- (global second-tier) city by the Globalization and World Cities Research Network,[19] a new Chinese first-tier city[21] and also a pioneering area for China-Africa economic and trade cooperation.[22] Known as the "Construction Machinery Capital of the world", Changsha has an industrial chain with construction machinery and new materials as the main industries, complemented by automobiles, electronic information, household appliances, and biomedicine.[23][24]

Since the 1990s, Changsha has begun to accelerate economic development, and then achieved the highest growth rate among China's major cities during the 2000s.[25] The Xiangjiang New Area, the first state-level new area in Central China, was established in 2015.[26] Changsha also has a prominent media and publishing industry, and has been named the first "UNESCO City of Media Arts" in China.[37] Changsha is home to the Hunan Broadcasting System (HBS), the most influential provincial TV station in China.[38][39]

In 2017, Changsha made its way into the 1-trillion-yuan GDP club, becoming the 13th city in China with a GDP of one trillion yuan (154 billion US dollars).[61] Moreover, the financial news portal Yicai.com released its 2017 ranking of China's new first-tier cities, and Changsha was a newcomer.[62] As of 2020, more than 164 Global 500 companies have established branches in Changsha.[63] As a new first-tier city, Changsha is rated #10 in terms of its commercial worth.[64]

As of 2021, Changsha's GDP exceeded RMB 1.327 trillion (US$208 billion in nominal and US$318 billion in PPP), making it the 5th most wealthy city in the South-Central China region after Shenzhen, Guangzhou, Hong Kong, and Wuhan and the 2nd richest city in the Central China region after Wuhan.[65][66] Changsha's GDP (nominal) was US$208 billion in 2021, exceeding that of Ukraine and Hungary, with GDPs of US$200 billion and US$182 billion, the 22nd and 23rd largest economies in Europe respectively.[67] Changsha has also led the development of the night economy and as of 2021, it ranked 2nd nationwide after Chongqing in terms of nighttime economic power according to the "China City Night Economy Impact Report 2021-2022".[68]

According to the Hurun Global Rich List, Changsha ranked among the top 35 cities globally as of 2022,[69][70] and as of 2024, it ranked first in the Central China region and 9th in Greater China (after Beijing, Shanghai, Shenzhen, Hong Kong, Hangzhou, Taipei, Guangzhou, and Ningbo) in terms of resident billionaires.[71]

Changsha's nominal GDP is projected to be among the world's top 50 largest cities according to a study by Oxford Economics in 2035[72] and its nominal GDP per capita will reach US$41,000 in 2030.[73]

Development Zones

editThe Changsha ETZ was founded in 1992. It is located in Xingsha in eastern Changsha. The total planned area is 38.6 km2 (14.9 sq mi) and the current[when?] area is 38.6 km2 (14.9 sq mi). Near the zone are National Highways 319 and 107 as well as the G4 Beijing–Hong Kong and Macau Expressway. The zone is also very close to Changsha's downtown area and the railway station, while the distance between the zone and the city's airport is a mere 8 km (5.0 mi). The major industries in the zone include the high-tech industry, the biology project technology industry, and the new material industry.[74]

The Liuyang ETZ is a national biological industry base created on 10 January 1998, located in Dongyang Town. Its pillar industry comprises biological pharmacy, Information technology and Health food. As of 2015[update], It has more than 700 registered enterprises. The total industrial output value of the zone hits 85.6 billion yuan (US$13.7 billion) and its business income is 100.2 billion yuan (US$16.1 billion).[75] Its builtup area covers 16.5 km2 (6.4 sq mi).[76]

Tourism

editPlaces of interest

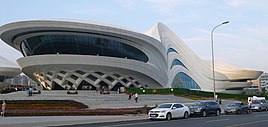

editTourism is a major industry in Changsha. Changsha has been consistently ranked as China's top tourist city.[77][78] There are several sites in Changsha, notably the Yuelu Academy and the Changsha Meixihu International Culture and Arts Centre, a cultural complex designed by the British firm Zaha Hadid Architects overlooking the Meixi Lake at the Meixihu subdistrict of the city. Others include the Young Mao Zedong statue on Orange Isle, Meixi Lake Park, Changsha IFS Tower, Window of the World, Kaifu Temple and Changsha Ice World.[79]

Mt.Yuelu

editYuelu Mountain is named after the "Nanyue Ji" written in the Liu and Song dynasties in the Southern and Northern dynasties, which states that "the surrounding area of Nanyue is eight hundred miles, with Huiyan as the head and Yuelu as the foot." Yuelu Mountain is located on the west bank of the Xiangjiang River in Yuelu District, Changsha City, Hunan Province; Orange Island is located in the middle of the Xiangjiang River, running through the center of the river from south to north, looking at Yuelu to the west and the ancient city to the east. There are 977 species of plants in 559 genera and 174 families in Yuelu Mountain Scenic Area. They are mainly typical subtropical evergreen broad-leaved forests and subtropical warm coniferous forests. In some areas, large areas of native evergreen broad-leaved secondary forests are preserved. A large number of precious endangered tree species and ancient and famous trees.

Orange Island

editOrange Island is located in the center of the Xiangjiang River in Yuelu District, Changsha City, Hunan Province. The original area is about 17 hectares, and the overall developed land area of the scenic spot reaches 91.64 hectares. It is the largest sandbar among the many alluvial sandbars in the lower reaches of the Xiangjiang River, and is known as "China's First Continent" . Orange Island has Mao Zedong Youth Art Sculpture, Wen Tiantai and other attractions. According to historical records, Orange Island was formed in the second year of Yongxing (305), the second year of Emperor Hui of the Jin dynasty. It was formed by the alluvial accumulation of rapids and sand and gravel.

Hua Ming Lou

editHuaming Tower: Liu Shaoqi's former residence is a national high-end tourist attraction in China and a national key cultural relics protection unit.Huaming Tower, formerly known as Huamen Tower, is a beautiful town in the southeast of Ningxiang City, Changsha City, Hunan Province. It is the former residence of Comrade Liu Shaoqi, the revolutionary great man and former president of the country.

Hunan Museum

editHunan Museum, located at No. 50 Dongfeng Road, Kaifu District, Changsha City, Hunan Province, is one of the first batch of national first-level museums in China, one of the eight national key museums jointly built by the central and local governments, and the largest comprehensive history and art museum in Hunan Province. The Hunan Provincial Museum was founded in the 23rd year of Guangxu's reign in the Qing dynasty (1897), and the current site is its new museum.

Demographics

editAs of the 2020 Chinese census, Changsha was home to 10,047,914 people, whom 7,355,198 lived in its built-up (or metro) area made of the 6 urban Districts plus Changsha County largely conurbated. The majority of people living in Changsha are Han Chinese. A sizeable population of ethnic minority groups also live in Changsha. The three largest are the Hui, Tujia, and Miao peoples. The 2000 census showed that 48,564 members of ethnic minorities live in Changsha, 0.7% of the population. The other minorities make up a significantly smaller part of the population. Twenty ethnic minorities have fewer than 1,000 members living in the city.[80][81]

Culture

editMedia

editHunan Broadcasting System is China's largest television after China Central Television (CCTV). Its headquarters is in Changsha and produces some of the most popular programs in China, including Super Girl. These programs have also brought a new entertainment industry into the city, which includes singing bars, dance clubs, theater shows, as well as related businesses including hair salons, fashion stores, and shops for hot spicy snacks at night (especially during summer). While Changsha has developed into an entertainment hub, the city has also become increasingly westernized and has attracted a growing number of foreigners.

Cuisine

editVarious types of cuisine are found in Changsha, yet the hot and spicy Hunan cuisine typical of the region remains the most popular. The snack chain Juewei Duck Neck, which now has over 10,000 outlets, originates from Changsha.

The city has its own siu yeh culture.

In May 2008, the BBC broadcast, as part of its Storyville documentary series, the four-part The Biggest Chinese Restaurant in the World, which explored the inner workings of the 5,000-seating-capacity West Lake Restaurant (Xihu Lou Jiujia) in Changsha.

During the Warring States period, Qu Yuan, a great patriotic poet, recorded many dishes in Hunan in his famous poem "The Soul"(招魂). During the Western Han dynasty, there were 109 varieties of dishes in Hunan, and there were nine categories of cooking methods. After the Six Dynasties, Hunan's food culture was rich and active. The Ming and Qing dynasties are the golden age for the development of Hunan cuisine. The unique style of Hunan cuisine is basically a foregone conclusion. At the end of the Qing dynasty, there were two kinds of Hunan cuisine restaurants in Changsha. In the early years of the Republic of China, the famous Dai (Yang Ming) School, Sheng (Shan Zhai) School, Xiao (Lu Song) School, and Zuyu School appeared in various genres, which laid the historical status of Hunan cuisine. Since the founding of New China, especially since the reform and opening up, it has been better developed.[82]

Sports

editChangsha has one of China's largest multi-purpose sports stadiums—Helong Stadium, with 55,000 seats. The stadium was named after the Communist military leader He Long. It is the home ground of local football team Hunan Billows F.C., which plays in China League Two. The more modest 6,000-seat Hunan Provincial People's Stadium, also located in Changsha, is used by the team for their smaller games.[83]

Historical culture

editChangsha hosts the Hunan Provincial Museum. 180,000 historical significant artifacts ranging from the Zhou dynasty to the recent Qing dynasty are hosted in the 51,000 acres (210 km2; 80 sq mi; 21,000 ha) of space in the museum.[84]

Mawangdui is a well-known tomb located 22 kilometres (14 mi) east of Changsha.[85][86] It was discovered with numerous artifacts from the Han dynasty. Numerous Silk Funeral banners surround the tomb, along with a wealth of classical texts.[87][88] The tomb of Lady Dai lies in Mawangdui is well known due to its well-preserved state: scientists were able to detect blood, conduct an autopsy and determined that she died of heart disease due to a poor diet.[89][90]

Changsha is a sister city with St. Paul, Minnesota. St. Paul is developing a China garden at Phalen Park, based on the design of architects from Changsha.[91] Current plans include a pavilion replicating one in Changsha, while in return St. Paul will send the city five statues of the Peanuts characters. They will be placed in Phalen's sister park, Yanghu Wetlands.[92]

Education and research

editResearch and Innovation

editChangsha is the birthplace of super hybrid rice, Yinhe-1, the first China's supercomputer built in the 1980s,[93] the Tianhe-1 supercomputer, China's first laser 3D printer,[35] and China's first domestic medium-low speed maglev line.[36] In November 2010, the National Supercomputing Changsha Center was established at Hunan University, becoming the first National Supercomputing Center in Central China and third National Supercomputing Center in China, after those in Tianjin and Shenzhen.[94]

Changsha is a major city for research and innovation in Central China, as well as in the Asia-Pacific region.[95][96] It ranked 23rd globally, 15th in the Asia & Oceania region, 13th in China, 5th in the South Central region after (Guangzhou, Wuhan, Hong Kong and Shenzhen), and 2nd in the Central China region after Wuhan by scientific research outputs, as tracked by the Nature Index 2024 Science Cities.[97]

Changsha was also ranked 32nd globally and 3rd in the South Central region after (Shenzhen–Hong Kong–Guangzhou and Wuhan) in the "Top 100 Science & Technology Cluster Cities" rankings based on "publishing and patent performance" released by the Global Innovation Index 2024.[98]

As of 2020, Changsha ranked 8th in the top 10 China's innovation-oriented cities,[99] and 6th (behind Shenzhen, Hangzhou, Shanghai, Chengdu and Beijing) in the Top 10 China's most attractive cities for talent, according to the 21st Century Business Herald report.[100] Changsha has held the title "China's Leading Smart City" since 2021.[101] As of 2021, Changsha had 97 independent scientific research institutions, 14 national engineering and technology research centers, 15 national key engineering and technology laboratories, and 12 national enterprise technology centers.[102]

Colleges and universities

editChangsha has long been the seat of several ancient schools and academies. The Yuelu Academy (later to become Hunan University) was one of the four most prestigious academies in China over the last 1000 years.[103] The city is also the site of the Hunan Medical University (later to become Central South University), which was established in 1914.

As of June 2023, Changsha hosts 59 institutions of higher education (excluding adult colleges), ranking 8th nationwide and 4th among all cities in the South Central China region after Guangzhou, Wuhan and Zhengzhou.[31] Changsha ranked among the top 10 cities in the whole country and among the top three cities in South Central China region with strong education based on an evaluation of Chinese universities' discipline levels, including A+, A, and A− issued by the Ministry of Education as of 2020.[104]

National key public universities

There are three Project 985 universities in Changsha: Central South University, Hunan University, and the National University of Defense Technology, the third highest among all cities in China after Beijing and Shanghai.[105] Hunan Normal University is the key construction university of the national 211 Project. These four national key universities are Double First-Class Construction. Changsha, the provincial capital of Hunan Province, is home to a significant number of top-tier educational institutions.[33] Specifically, among the twelve universities in Hunan Province included in the 2022 U.S. News & World Report Best Global University Ranking, eight are based in Changsha, accounting for almost two-thirds of the total.[32][106] This concentration of highly ranked universities further solidifies Changsha's status as a prominent hub for higher education within the province.

Hunan University and Central South University are included in the world's top 300 in several global university-rankings, including the Academic Ranking of World Universities, the U.S. News & World Report Best Global University Ranking, the CWTS Leiden Ranking and the Center for World University Rankings,.[32][107][108][109] As of 2024, these two universities are placed among the world's top 50 universities ranked by the Nature Index.[110]

Hunan Normal University and the National University of Defense and Technology were ranked in the world's top 501-600 of the Academic Ranking of World Universities.[111]

- Central South University (Project 211, Project 985, Double First Class University)

- Hunan University (Project 211, Project 985, Double First Class University)

- Hunan Normal University (Project 211, Double First Class University)

- National University of Defense Technology (Project 211, Project 985, Double First Class University)

Provincial key public universities

Changsha University of Science and Technology and Hunan Agricultural University were ranked in the world's top 701 and 801 respectively of the Academic Ranking of World Universities.[111] Central South University of Forestry and Technology was ranked # 1429 in the 2022 Best Global Universities by the U.S. News & World Report Best Global University Ranking.[32] Hunan University of Chinese Medicine was ranked the best in the Central China region and 26th nationwide among Chinese medical universities,[112] and ranked #1854 globally in the 2023 Best Global Universities by the U.S. News & World Report Best Global University Ranking.[106] Hunan University of Technology and Business was ranked # 2341 in the world by the University Ranking by Academic Performance 2022–2023.[113]

- Central South University of Forestry and Technology

- Changsha University of Science and Technology

- Hunan Agricultural University

- Hunan First Normal University

- Hunan University of Technology and Business

- Hunan University of Chinese Medicine

General undergraduate universities (public)

- Changsha University

- Hunan University of Finance and Economics

- Hunan Police Academy

- Hunan Women's University

- Changsha Normal University

General undergraduate universities (private)

- Changsha Medical University

- Hunan International Economics University

- Hunan Institute of Information Technology

Vocational and technical colleges/universities

- Changsha Aeronautical Vocational and Technical College

- Changsha Social Work College

- Hunan Mass Media Vocational and Technical College

Note: Institutions without full-time bachelor programs are not listed.

International schools

editNotable high schools

edit- Yali High School

- The High School Affiliated to Hunan Normal University

- Changjun High School

- The First High School of Changsha

Notable primary schools

edit- Changsha Experimental Primary School

- Datong Primary School

- Qingshuitang Primary School

- Shazitang Primary School

- Yanshan Primary School

- Yucai Primary School

- Yuying Primary School

Transportation

editChangsha is well connected by roads, river, rail, and air transportation modes, and is a regional hub for industrial, tourist, and service sectors.

The city's public transportation system consists of an extensive bus network with over 100 lines. Changsha Metro is planning a 6-line network.[114] Metro Line 2 opened on 29 April 2014[115] and 20 stations for Line 2[114] opened on 28 June 2016.[116][117] A further four lines are planned for construction by 2025.[115] Line 3 will run southwest–northeast and will be 33.4 kilometres (20.8 mi) long, Line 4 northwest-southeast and 29.1 kilometres (18.1 mi) long.[118] A maglev link running 16.5 kilometres (10.3 mi) between Changsha South station and Changsha airport opened in April 2016, with a construction cost of €400m.[115][119][120] Connecting Changsha with Zhuzhou and Xiangtan, Changzhutan Intercity Rail opened on 26 December 2016.[121]

The G4, G4E, G4W2, G5513 and G0401 of National Expressways, G107, G106 and G319 of National Highways, S20, S21, S40, S41, S50, S60 and S71 of Hunan provincial Expressways, connect the Changsha metro area nationally. There are three main bus terminals in Changsha: the South Station, East Station and West Station, dispatching long- and short-haul trips to cities within and outside the province of Hunan. Changsha is surrounded by major rivers, including the Xiang (湘江) and its tributaries such as the Liuyang, Jin, Wei, Longwanggang and Laodao. Ships mainly transport goods from Xianing port in North Changsha domestically and internationally.[citation needed]

Changsha Railway Station is in the city center and provides express and regular services to most Chinese cities via the Beijing–Guangzhou and Shimen–Changsha Railways. The Changsha South Railway Station is a new high-speed railway station in Yuhua district on the Beijing–Guangzhou High-Speed Railway (as part of the planned Beijing–Guangzhou–Shenzhen–Hong Kong High-Speed Railway). The station, with eight platforms,[122] opened on 26 December 2009.[123] Since then passenger volume has increased greatly.[124] The Hangzhou-Changsha-Huaihua sector of the Shanghai-Changsha-Kunming high-speed railway entered service in 2014.

Changsha Huanghua International Airport is a regional hub for China Southern Airlines. The airport has daily flights to major cities in China, including Beijing, Shanghai and Guangzhou, as well as Hong Kong and Macau. Other major airlines also provide daily service between Changsha and other domestic and international destinations. The airport provides direct flights to 45 major international cities, including Taipei, Los Angeles, Singapore, Seoul, Pusan, Osaka, Tokyo, Kuala Lumpur, London (Heathrow Airport), Frankfurt and Sydney.[125] As of 5 August 2016[update] the airport handled 70,011 people daily.[126] Due to the global effect of the COVID-19 pandemic, Changsha Huanghua International Airport was the 34th busiest airport in the world in 2020, making its debut in the world's top 50 busiest airports for the first time.[127]

City honors and rankings

edit- The city ranked 27th in the world by numbers of 150m+completed buildings as of 2021[128]

- Changsha IFS Tower T1 ranked the 16th tallest completed building in the world as of 2020[129]

- China's Top 2nd Most Influential City of Nighttime Economy in 2022[68]

- Top 10 "China's Happiest Cities"[130][131]

- One of China's new first-tier cities in 2017[132]

- 32nd globally in the "Top 100 Science & Technology Cluster Cities" rankings by "publishing and patent performance" released by the Global Innovation Index 2024[98]

- 23rd globally and 15th in the Asia & Oceania region in the "Top 200 cities" by scientific research outputs released by the Nature Index 2024 Science Cities Rankings.[97]

- 67th worldwide in the Global Cities Outlook rankings of the 2018 Global Cities Report released by AT Kearney[133][134]

- 68th worldwide in terms of "Urban Economic Competitiveness" in 2019 jointly released by the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences (CASS) and the United Nations Programme for Human Settlements (UN-Habitat)[135]

- The first Chinese city to be recognized as a "World Creative City in Media Arts" by UNESCO[136][137]

- Changsha was classified as a Beta- (global second tier) city together with Manchester (the U.K), Geneva (Switzerland) and Seattle (the U.S) by the Globalization and World Cities Research Network.[138]

- The 10 fastest growing cities in the world[139][140][30] Changsha's nominal GDP is projected to be among the world top 50 largest cities according to a study by Oxford Economics in 2035,[72] and its nominal GDP per capita will reach US$41,000 in 2030.[73]

International relations

editTwin towns – sister cities

editBy the end of June 2018, Changsha has established friendly city relationship with 49 foreign cities.[141]

Changsha is twinned with:[142]

- Brazzaville, Congo

- Gumi, Gyeongsangbuk-do, South Korea

- Kagoshima, Kagoshima, Japan

- Mogilev, Mogilev Region, Belarus

- Mons, Hainaut, Belgium

- New Haven, Connecticut, United States

- Jersey City, New Jersey, United States

- Annapolis, Maryland, United States

- Saint Paul, Minnesota, United States

- Fribourg, Canton of Fribourg, Switzerland

- City of Auburn, New South Wales, Australia

- Entebbe, Uganda

Consulates General/Consulates

editNotable people

editThe following people are from the Greater Changsha Metropolitan Region:

- Mao Zedong – Founding father of the People's Republic of China

- Zeng Guofan – Most influential politician of China in 19th century

- Liu Shaoqi – President of the People's Republic of China (PRC), 1959–1968

- Zhu Rongji – Premier of the People's Republic of China, 1998–2003

- Hu Yaobang – General Secretary of the Chinese Communist Party (1982–1987)

- Yang Kaihui – Mao Zedong's second wife

- Huang Xing – Chinese revolutionary leader and the first army commander-in-chief of the Republic of China

- Tian Han – Author of the lyrics to "March of the Volunteers", China's national anthem

- Wang Tao – Economist

- Zhou Guangzhao – Theoretical physicist and recipient of the "Two Bombs, One Satellite" Meritorious Award

- Zhou Jianping – Aerospace engineer and chief designer of China Manned Space Program

- Qi Xueqi – General in the Kuomintang (KMT)

- Lei Feng – A People's Liberation Army's cultural icon

- Liang Heng – Writer and literary scholar

- Tan Dun – Contemporary composer (soundtracks for the films Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon and Hero)

- Huang Zuqia – Theoretical and nuclear physicist

- Tang Sulan – Writer and politician

- Zhang Ye – Singer

- Xiong Ni – Olympic male diver and gold medalist

- Leo Li – Actress and singer-songwriter

- Li Xiaopeng – Olympic male gymnast and gold medalist

- Liu Yun – Actress

- Liu Xuan – Olympic female gymnast and gold medalist

- Meng Jia – Singer and actress, former member of the Korean-Chinese girl group Miss A

- Lay (entertainer) – A member of South Korean-Chinese boy band under SM entertainment, Exo

- Qi Baishi – Painter

- Shen Wei – Dancer and the choreographer of modern dance for the 2008 Beijing Olympics

- He Jiong – One of the most famous TV show hosts in China

- Lexie Liu – Singer-songwriter and rapper

- Can Xue – Avant-garde fiction writer

- Xue Yiwei - Writer living in Montreal[144]

- Zhao Wendi (born 2001) - footballer

Astronomy

editChangsha is represented by the star Zeta Corvi in a Chinese constellation.[145]

See also

editNotes

edit- ^ UK: /tʃæŋˈʃɑː/; US: /tʃɑːŋ-/;[5] simplified Chinese: 长沙; traditional Chinese: 長沙; Changsha Xiang Chinese: [tsã˩˧ sɔ˧] (), Mandarin pinyin: Chángshā ()

References

edit- ^ "Changsha City". Archived from the original on 7 February 2020. Retrieved 24 July 2022.

- ^ "Major Agglomerations of the World - Population Statistics and Maps". Archived from the original on 7 July 2023. Retrieved 30 July 2023.

- ^ "2022年湖南省各市州地区生产总值(三季度".

- ^ "National Human Development Report 2019: China". 12 October 2020.

- ^ "Changsha". Lexico UK English Dictionary. Oxford University Press. Archived from the original on 19 May 2021.

- ^ "17 Chinese cities have a population of over 10 million in 2021". www.ecns.cn. Archived from the original on 12 August 2022. Retrieved 24 August 2022.

- ^ "Supersized cities: China's 13 megalopolises". Archived from the original on 21 July 2012. Retrieved 23 July 2012.

- ^ "State Council on the issuance of the "Thirteenth Five-Year Plan" modern comprehensive transport system development plan" Archived 30 June 2017 at the Wayback Machine State Council, State Development [2017] No. 11

- ^ Institute of Linguistics, CASS. Language atlas of China. The Commercial Press. Beijing. December, 2012.

- ^ "Húnán (China): Prefectural Division & Major Cities - Population Statistics 2020". www.citypopulation.de. Archived from the original on 11 February 2022. Retrieved 12 June 2022.

- ^ Changsha Municipal Institute of Cultural Relics and Archaeology. Archaeological Discoveries and Studies of Ancient City Sites in Changsha. Hunan Yuelu Publishing House. 1 December 2016.

- ^ Yi Zhou Shu·Wang Hui Archived 8 June 2021 at the Wayback Machine:"长沙鳖,其西,鱼复鼓钟钟牛"

- ^ Wang Xiga. The History of Changsha. Social Science Literature Press. December, 2014.

- ^ Fan Chengda (1126-1193). Shigushanji(石鼓山记):"天下有书院四:徂徕、金山、岳麓、石鼓。"

- ^ Institute of Changsha Culture, Changsha University. The prosperity of commerce in ancient Changsha and its causes (below) Journal of Changsha University. 2011 No. 1.

- ^ Lei Jing (2008). "A Study of the Modernization Process in Changsha 1800-1949". Xiangtan University, 2008.

- ^ a b "Strategy Basics - Yangtze River Economic Belt" Archived 13 June 2021 at the Wayback Machine Office of the Leading Group for Promoting the Development of the Yangtze River Economic Belt. 13 July 2019.

- ^ a b ""Hunan One Belt, One Road Official Website"". Archived from the original on 8 June 2021. Retrieved 8 June 2021.

- ^ a b "GaWC - The World According to GaWC 2020". www.lboro.ac.uk. Archived from the original on 24 August 2020. Retrieved 20 March 2022.

- ^ a b "Ranking of Chinese Cities' Business Attractiveness 2022". www.yicaiglobal.com. Archived from the original on 1 June 2022. Retrieved 12 June 2022.

- ^ a b "15 new Chinese first-tier cities". www.chinadaily.com.cn. Archived from the original on 12 June 2022. Retrieved 12 June 2022.

- ^ a b "Hunan: Building an pioneering zone for in-depth China-Africa economic and trade cooperation" Archived 7 June 2021 at the Wayback Machine Forum on China-Africa Cooperation. 19 January 2021.

- ^ a b "Study on industrial restructuring and upgrading in Changsha" Archived 8 June 2021 at the Wayback Machine Bureau of Statistics of Changsha. 16 Oct. 2017.

- ^ a b "Changsha: "Capital of Construction Machinery" explores world coordinates" Archived 13 August 2020 at the Wayback Machine Xinhuanet. 20 May 2019.

- ^ a b Zhang Huaizhong. "Changsha's GDP grows 460% in 10 years, leading the country in growth" Archived 23 August 2016 at the Wayback Machine People's Daily Online Finance. 22 August 2016.

- ^ a b "Central China's First State-Level New Area Xiangjiang New District Officially Launched" Archived 31 January 2018 at the Wayback Machine Ifeng Finance. 24 May 2015.

- ^ "Clusters driving Changsha's push for global recognition - Chinadaily.com.cn". epaper.chinadaily.com.cn. Retrieved 18 November 2024.

- ^ "Changsha - The Skyscraper Center". www.skyscrapercenter.com. Archived from the original on 15 May 2020. Retrieved 11 February 2024.

- ^ a b "National Human Development Report 2019: China | Human Development Reports". www.hdr.undp.org. January 2019. Archived from the original on 12 October 2020. Retrieved 12 October 2020.

- ^ a b c d "Competitive Cities: Changsha, China – coordination, competition, construction and cars". blogs.worldbank.org. 23 February 2016. Archived from the original on 8 November 2020. Retrieved 11 May 2020.

- ^ a b "全国普通高等学校名单 (National List of Higher Education Institutions)". Government Portal Website of the Ministry of Education of the People's Republic of China. 15 June 2023. Archived from the original on 21 June 2024. Retrieved 28 December 2023.

- ^ a b c d "US News Best Global Universities Rankings in Changsha". U.S. News & World Report. 26 October 2021. Archived from the original on 16 April 2022. Retrieved 26 October 2021.

- ^ a b "Nature Index 2018 Science Cities | Nature Index Supplements | Nature Index". www.natureindex.com. Archived from the original on 2 October 2020. Retrieved 22 September 2020.

- ^ "Leading 200 science cities 2024 | | Supplements | Nature Index". www.nature.com. Retrieved 20 November 2024.

- ^ a b Municipal Local Records Editorial Office. "Changsha City Profile" Archived 13 March 2021 at the Wayback Machine Official website of Changsha, China. 13 April 2021.

- ^ a b "Medium-Low Speed Maglev in Changsha" Archived 12 May 2021 at the Wayback Machine CRRC ZELC EUROPE.

- ^ a b "Changsha | Creative Cities Network". en.unesco.org. Archived from the original on 5 July 2018. Retrieved 24 July 2022.

- ^ a b "TV ratings rankings 2009-2017 Hunan TV No. 1 for the ninth consecutive year" Archived 1 February 2018 at the Wayback Machine tvtv.hk. 14 January 2018.

- ^ a b "2020 "TV Landmark" and "Voice of the Times" List Released" Archived 8 June 2021 at the Wayback Machine Xinhuanet. 7 December 2017.

- ^ 中国古今地名大词典 [Dictionary of Chinese Place-names Ancient and Modern]. Shanghai: Shanghai Lexicographical Publishing House. 2005. p. 505.

- ^ www.chinaeducenter.com. "Changsha City Guide – China Education Center". www.chinaeducenter.com. Archived from the original on 2 February 2017. Retrieved 19 January 2017.

- ^ Lander, Brian; Ling, Wenchao; Wen, Xin (2023). State and Local Society in Third Century South China: Administrative Documents Excavated at Zoumalou, Hunan. Leiden: Brill.

- ^ Murck, Alfreda (1996). "The "Eight Views of Xiao-Xiang" and the Northern Song Culture of Exile". Journal of Song-Yuan Studies (26): 113–144. ISSN 1059-3152. JSTOR 23496050. Archived from the original on 17 November 2022. Retrieved 17 November 2022.

- ^ William T. Rowe. China's Last Empire: The Great Qing. (Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, History of Imperial China, 2009; ISBN 9780674036123), p. 162-163 Archived 3 September 2023 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Daniel McMahon, "The Yuelu Academy and Hunan's Nineteenth-Century Turn toward Statecraft", Late Imperial China 26.1 (2005): 72–109 Project MUSE Archived 3 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ Van De Ven, Hans J., War and Nationalism in China, 1925–1945, pg. 237.

- ^ Duxiu Chen; Gregor Benton (1998). Gregor Benton (ed.). Chen Duxiu's last articles and letters, 1937–1942 (illustrated ed.). University of Hawaii Press. p. 45. ISBN 0824821122. Archived from the original on 3 September 2023. Retrieved 20 February 2016.

24. Xi'an never fell. Under the Guonaindang General Xue Yue, Changsha was successfully defended three times against the Japanese; Changsha (and the vital Guangzhou-Hankou Railway) did not fall to the Japanese until early 1945.

- ^ Natkiel, Richard (1985). Atlas of World War II. Brompton Books Corp. p. 147. ISBN 1-890221-20-1.

- ^ Taylor, Jay (2009). The Generalissimo: Chiang Kai-shek and the Making of Modern China. Belknap Press of Harvard University Press. p. 158. ISBN 9780674033382.

- ^ a b 长沙统计年鉴2017 (in Chinese (China)). Government of Changsha. Archived from the original on 17 April 2018. Retrieved 28 December 2019.

Section 1-1, "自然环境" (Natural environment)

- ^ sina.com (2013-5-8) Archived 19 April 2018 at the Wayback Machinechina-zjj Archived 20 April 2018 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Changsha". www.xinli110.com. Archived from the original on 17 November 2012. Retrieved 1 April 2019.

- ^ a b "Environmental Resources in Changsha". www.changsha.gov.cn. Archived from the original on 14 August 2018. Retrieved 1 April 2019.

- ^ "China Meteorological Administration". Archived from the original on 21 September 2013. Retrieved 21 February 2013.

- ^ "Index" 中国气象数据网 – WeatherBk Data. China Meteorological Administration. August 2010. Archived from the original on 23 September 2017. Retrieved 9 November 2018.

- ^ CMA台站气候标准值(1991-2020) (in Chinese). China Meteorological Administration. Archived from the original on 4 April 2023. Retrieved 11 April 2023.

- ^ "Changsha Climate Normals 1991-2020". NOAA. Archived from the original on 8 May 2024.

- ^ "13 cities in China join the 1 trillion yuan GDP club in 2017". chinaplus.cri.cn. Archived from the original on 24 February 2021. Retrieved 7 May 2020.

- ^ "Per capita GDP in 14 Chinese cities hits $20,000 in 2020". global.chinadaily.com.cn. Archived from the original on 11 April 2023. Retrieved 1 September 2022.

- ^ "In 2021, the GDP of each city and state in Hunan will exceed US$20,000 per capita in Changsha". Retrieved 15 June 2022.[permanent dead link]

- ^ "Two more cities join China's trillion yuan GDP club in 2017 - Chinadaily.com.cn". www.chinadaily.com.cn. Archived from the original on 4 July 2020. Retrieved 7 May 2020.

- ^ "2017"新一线"城市排行榜发布成都、杭州、武汉蝉联三甲郑州、东莞新晋入榜". www.yicai.com. Archived from the original on 18 July 2020. Retrieved 7 May 2020.

- ^ The Rise of Central China is Gaining Momentum - Hunan Chapter-Changsha: Endless Innovation to Create a New High Ground for Business Environment Archived 8 June 2021 at the Wayback Machine CNR News. 23 Sep 2020.

- ^ "Top 10 new first-tier cities by commercial appeal". www.chinadaily.com.cn. Archived from the original on 30 October 2022. Retrieved 30 October 2022.

- ^ "Decoding China's 2021 GDP Growth Rate: A Look at Regional Numbers". China Briefing News. 7 February 2022. Archived from the original on 19 August 2022. Retrieved 1 September 2022.

- ^ "GDP (current US$) - Hong Kong SAR, China | Data 2021". data.worldbank.org. Archived from the original on 1 September 2022. Retrieved 1 September 2022.

- ^ "GDP (current US$) - Ukraine, Hungary | Data". data.worldbank.org. Archived from the original on 1 September 2022. Retrieved 1 September 2022.

- ^ a b "Top 10 cities in China by nighttime economic power". www.chinadaily.com.cn. Archived from the original on 5 September 2022. Retrieved 5 September 2022.

- ^ "胡润百富 - 资讯 - 2022家大业大酒·胡润全球富豪榜". www.hurun.net. Archived from the original on 25 May 2022. Retrieved 9 April 2022.

- ^ "Hurun Global Rich List 2022". www.hurun.net. Archived from the original on 7 April 2022. Retrieved 9 April 2022.

- ^ "胡润百富 - 资讯 - 2024衡昌烧坊·胡润百富榜". www.hurun.net. Retrieved 29 October 2024.

- ^ a b "China's cities to rise to the top ranks by 2035". Nikkei Asia. Archived from the original on 20 August 2020. Retrieved 2 November 2020.

- ^ a b "World's Richest Cities in 2030, and Where Southeast Asian Cities Stand | Seasia.co". Good News from Southeast Asia. Archived from the original on 9 November 2020. Retrieved 3 November 2020.

- ^ Changsha National Economic and Technology Development Zone Archived 26 August 2011 at the Wayback Machine. RightSite.asia. Retrieved on 2011-08-28.

- ^ About Liuyang ETZ: letz.gov.cn Archived 24 February 2017 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ 浏阳经开区2016年经济工作报告 [Development Report of LETZ in 2016]. Liuyang People's Government. Archived from the original on 24 February 2017.

- ^ "Top 10 Chinese destinations for summer vacations". www.chinadaily.com.cn. Archived from the original on 30 October 2022. Retrieved 30 October 2022.

- ^ "Top 10 most popular destinations during Dragon Boat Festival". www.chinadaily.com.cn. Archived from the original on 30 October 2022. Retrieved 30 October 2022.

- ^ "IMPOSSIBLE BUILDS: Episode 5 Preview | Ice World". PBS. Archived from the original on 10 December 2021. Retrieved 9 December 2021.

- ^ 湖南人口信息服务网 – 人口普查资料. Hunan Bureau of Statistics. Archived from the original on 31 March 2016. Retrieved 23 January 2017.

- ^ 中华人民共和国国家统计局. www.stats.gov.cn. Archived from the original on 9 May 2011. Retrieved 23 January 2017.

- ^ "Hunan cuisine". www.china.com.cn. Archived from the original on 16 November 2014. Retrieved 1 April 2019.

- ^ "Hunan Xiangtao FC". soccerway.com. Archived from the original on 13 February 2013. Retrieved 25 December 2011.

- ^ "Hunan Provincial Museum". www.hnmuseum.com. Archived from the original on 2 February 2017. Retrieved 28 January 2017.

- ^ Buck, David D., 1975, Three Han Dynasty Tombs at Ma-Wang-Tui. World Archaeology, 7(1): 30–45.

- ^ Lee, Sherman E., 1994, A History of Far Eastern Art, Fifth edition, Prentice Hall

- ^ Hsu, Mei-Ling, 1978, The Han Maps and Early Chinese Cartography. Annals of the Association of American Geographers, 68(1): 45–60

- ^ 马王堆汉墓陈列全景数字展厅--湖南省博物馆. www.hnmuseum.com (in Chinese (China)). Archived from the original on 18 October 2016. Retrieved 29 January 2017.

- ^ Harper, Don, 1998, Early Chinese Medical Literature: The Mawangdui Medical Manuscripts, Kegan Paul International

- ^ "A Selection of Artifacts from Mawangdui – Photo Gallery – Archaeology Magazine Archive". archive.archaeology.org. Archived from the original on 2 February 2017. Retrieved 29 January 2017.

- ^ Phalen Regional Park China Garden Archived 13 January 2017 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ St. Paul Chinese garden getting pavilion gift from sister city Archived 21 July 2017 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "The Race To Exascale". Asian Scientist Magazine. 19 July 2019. Archived from the original on 27 November 2022. Retrieved 27 November 2022.

- ^ "Hunan starts building supercomputing center". www.chinadaily.com.cn. 28 November 2010. Archived from the original on 11 October 2022. Retrieved 11 October 2022.

- ^ "Changsha, a Hub for China's Creative Industries". Discovery. 27 March 2019. Archived from the original on 6 March 2022. Retrieved 2 March 2021.

- ^ "Leading 200 science cities | Nature Index 2022 Science Cities | Supplements | Nature Index". www.nature.com. Archived from the original on 26 November 2022. Retrieved 26 November 2022.

- ^ a b "Leading 200 science cities | | Supplements | Nature Index". www.nature.com. Retrieved 20 November 2024.

- ^ a b "Science and Technology Cluster Ranking 2024". global-innovation-index. Archived from the original on 29 August 2024. Retrieved 29 August 2024.

- ^ "Top 10 China's innovation-oriented cities in 2020". www.chinadaily.com.cn. Archived from the original on 28 January 2021. Retrieved 2 March 2021.

- ^ "Top 10 most attractive cities for talent in 2020". www.chinadaily.com.cn. 14 January 2021. Archived from the original on 10 February 2021. Retrieved 2 March 2021.

- ^ "Changsha Named "China's Leading Smart City 2022"". www.enghunan.gov.cn. Retrieved 30 November 2022.

- ^ "Changsha City". enghunan.gov.cn. Archived from the original on 7 February 2020. Retrieved 24 July 2022.

- ^ Yeulu Academy, Changsha Archived 16 April 2011 at the Wayback Machine. Dm.hnu.cn. Retrieved on 2011-08-28.

- ^ 于小明. "Top 10 Chinese cities with strong education". www.chinadaily.com.cn. Archived from the original on 22 September 2020. Retrieved 22 September 2020.

- ^ "Project 211 and 985 - China Education Center". www.chinaeducenter.com. Archived from the original on 14 August 2020. Retrieved 19 June 2022.

- ^ a b "US News Best Global Universities Rankings: Hunan University of Chinese Medicine". U.S. News & World Report. 24 October 2022. Archived from the original on 14 July 2023. Retrieved 30 October 2022.

- ^ "ShanghaiRanking's Academic Ranking of World Universities". www.shanghairanking.com. Archived from the original on 15 August 2021. Retrieved 16 October 2021.

- ^ "World University Rankings 2023 | Global 2000 List | CWUR". cwur.org. Archived from the original on 1 July 2023. Retrieved 7 July 2023.

- ^ Studies (CWTS), Centre for Science and Technology. "CWTS Leiden Ranking". CWTS Leiden Ranking. Archived from the original on 2 February 2011. Retrieved 7 July 2023.

- ^ "2024 Research Leaders: Leading institutions | Nature Index". www.nature.com. Archived from the original on 23 June 2024. Retrieved 20 June 2024.

- ^ a b "ShanghaiRanking's Academic Ranking of World Universities". www.shanghairanking.com. Archived from the original on 15 August 2023. Retrieved 15 August 2023.

- ^ "ShanghaiRanking's Best Chinese Universities Ranking". www.shanghairanking.com. Archived from the original on 21 July 2023. Retrieved 21 July 2023.

- ^ "URAP - University Ranking by Academic Academic Performance". urapcenter.org. Archived from the original on 6 December 2020. Retrieved 5 July 2023.

- ^ a b 线路图 [Official Map]. hncsmtr.com (in Chinese). Changsha Metro Group Co., Ltd. Archived from the original on 29 April 2014. Retrieved 30 April 2014.

- ^ a b c "Changsha metro opens". railwaygazette.com. 29 April 2014. Archived from the original on 29 April 2014. Retrieved 30 April 2014.

- ^ 长沙地铁1号线正式开通试运营 告别单线出行迎来换乘时代_图片频道_新华网 (in Simplified Chinese). Xinhua News. Archived from the original on 25 October 2016. Retrieved 25 October 2016.

- ^ 长沙地铁1号线一期工程可研报告获批 2015年全面竣工 (in Chinese). Changsha News Online (长沙新闻网). 26 October 2010. Archived from the original on 18 June 2015. Retrieved 30 April 2014.

- ^ "Metro projects underway in Changsha, Xi'an, Wuhan and Xiamen". railwaygazette.com. 13 July 2011. Archived from the original on 21 October 2014. Retrieved 30 April 2014.

- ^ "Changsha airport maglev line openes". Railway Gazette. 4 April 2016. Archived from the original on 8 April 2016. Retrieved 4 April 2016.

- ^ Changsha to Construct Maglev Train Archived 16 January 2014 at the Wayback Machine, 2014-01-09

- ^ 广铁集团公司关于长株潭城际铁路开通运营的公告 (in Simplified Chinese). 12306.cn. 25 December 2016. Archived from the original on 25 December 2016. Retrieved 25 December 2016.

- ^ Huang, Chen (黄琛); Su Yi (2 January 2010). 长沙南站好多市民过眼瘾. 长沙晚报. 新民网. Archived from the original on 18 June 2015. Retrieved 21 June 2014.

- ^ 抢占先机 武广高速铁路通车长沙商圈又添新丁. 0731fdc.com news (in Chinese). 26 December 2009. Archived from the original on 3 March 2016. Retrieved 29 January 2019.

- ^ Bradsher, Keith (24 September 2013). "Speedy Trains Transform China". New York Times. Archived from the original on 26 September 2013. Retrieved 26 September 2013.

- ^ "???ALLP.list.sharingTitle.FLMP???". Archived from the original on 11 September 2016. Retrieved 24 August 2016.

- ^ 湖南省机场管理集团有限公司,贵宾服务 (in Simplified Chinese). Hunan Airport Management Group Co., Ltd. Archived from the original on 23 September 2016. Retrieved 9 September 2016.

- ^ "2020 Civil Airports Statistics Report". Ministry of Transport of the People's Republic of China. 9 April 2021. Archived from the original on 10 May 2021. Retrieved 16 September 2021.

- ^ "Changsha - The Skyscraper Center". www.skyscrapercenter.com. Archived from the original on 13 September 2014. Retrieved 8 May 2021.

- ^ "The 17 tallest buildings in the world right now, ranked, Business Insider - Business Insider Singapore". www.businessinsider.sg. Retrieved 9 May 2020.[permanent dead link]

- ^ "China selects happiest cities of 2019 - Xinhua | English.news.cn". www.xinhuanet.com. Archived from the original on 28 November 2019. Retrieved 7 May 2020.

- ^ "Official website of Changsha, China". en.changsha.gov.cn. Archived from the original on 25 February 2021. Retrieved 9 May 2020.

- ^ "2017"新一线"城市排行榜发布成都、杭州、武汉蝉联三甲郑州、东莞新晋入榜". www.yicai.com. Archived from the original on 18 July 2020. Retrieved 7 May 2020.

- ^ "Changsha appears on Global Cities lists- China.org.cn". www.china.org.cn. Archived from the original on 25 February 2021. Retrieved 7 May 2020.

- ^ 2018 Global Cities Report. AT Kearney. 2018.

- ^ "Changsha Ranks 68th Worldwide in Urban Economic Competitiveness-Hunan Government Website International-enghunan.gov.cn". enghunan.gov.cn. Archived from the original on 24 February 2021. Retrieved 9 May 2020.

- ^ "Changsha | Creative Cities Network". en.unesco.org. Archived from the original on 5 July 2018. Retrieved 7 May 2020.

- ^ "Changsha named UNESCO Creative City". www.chinadaily.com.cn. Archived from the original on 8 June 2020. Retrieved 7 May 2020.

- ^ "GaWC - The World According to GaWC 2018". www.lboro.ac.uk. Archived from the original on 3 May 2017. Retrieved 23 June 2020.

- ^ "长沙竞争力进全球"十快"居首_资讯频道_凤凰网". news.ifeng.com. Archived from the original on 3 September 2023. Retrieved 7 May 2020.

- ^ Edwards, Rhiannon (4 February 2016). "China's fastest-growing cities and why you should visit them". The Telegraph. ISSN 0307-1235. Archived from the original on 12 January 2022. Retrieved 7 May 2020.

- ^ "International Sister Cities of Changsha". Official website of Changsha, China. Archived from the original on 19 April 2021. Retrieved 13 October 2020.

- ^ "友好城市". changsha.gov.cn (in Chinese). Changsha. Archived from the original on 17 October 2020. Retrieved 13 October 2020.

- ^ "Consulate General of the Republic of Malawi in Changsha Opens-Hunan Government Website International-enghunan.gov.cn". www.enghunan.gov.cn. Retrieved 2 July 2023.

- ^ "The Fate of a Novel Amid China's Reform". University of California Los Angeles. Archived from the original on 14 September 2022. Retrieved 29 July 2022.

- ^ Star Name – R.H. Allen p.182 Archived 3 September 2023 at the Wayback Machine. Penelope.uchicago.edu. Retrieved on 2011-08-28.

External links

edit- Changsha Interactive Map, Information on Locations

- Changsha Government official website Archived 8 February 2014 at the Wayback Machine

- Changsha National High-Tech Industrial Development Zone Archived 9 February 2014 at the Wayback Machine