Cascade is an urban neighborhood abutting Downtown Seattle, Washington, United States, located adjacent to South Lake Union. It is bounded by: Fairview Avenue North on the west, beyond which is the rest of the Cascade Neighborhood; the Interstate 5 interchange for Mercer St to the north, beyond which is Eastlake; Interstate 5 on the east, beyond which is Capitol Hill; and Denny Way on the south, beyond which is Denny Triangle. It is surrounded by thoroughfares Mercer Street (eastbound), Fairview Avenue N. and Eastlake Avenue E. (north- and southbound), and Denny Way (east- and westbound). The neighborhood, one of Seattle's oldest, originally extended much further: west to Terry Avenue, south to Denny Hill (regraded away 1929–1931) on the South, and east to Melrose Avenue E through the area now obliterated by Interstate 5.[1] Some recent writers consider Cascade to omit the northern "arm" (east of Lake Union), while others extend it westward to cover most of South Lake Union.[2]

Cascade, Seattle | |

|---|---|

The Cascade Playground (former playground of the long-demolished Cascade School) | |

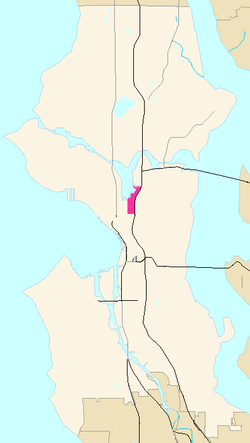

Cascade Highlighted in Pink | |

| Coordinates: 47°37′28″N 122°20′04″W / 47.62444°N 122.33444°W | |

| Country | United States |

| State | Washington |

| County | King |

| City | Seattle |

| Zip Code | 98109 |

| Area Code | 206 |

Historic structures in Cascade Neighborhood include St Spiridon's Orthodox Cathedral, Immanuel Lutheran Church, and several defunct laundry blocks. In 2007, a development named Alley24 was built around the New Richmond Laundry Building, a City of Seattle Landmark located between John and Thomas Streets and Yale and Pontius Avenues North. The historic façade was maintained in the new design by architecture firm NBBJ, who also relocated their headquarters to Alley24. The property is jointly owned by PEMCO and Paul Allen's development company Vulcan Inc.[3] Vulcan owns roughly approximately 6 acres in Cascade Neighborhood, a lower percentage of the land than in the rest of South Lake Union.[4]

History

editCascade grew up in the late 19th and early 20th century as a blue-collar neighborhood with a mixture of housing and one of the city's first industrial areas. It was the original home of St. Demetrios Greek Orthodox Church (built 1919–1921; congregation moved 1963; demolished 1995), and remains the home of St. Spiridon Russian Orthodox Cathedral (established 1895, present church completed 1938) and Immanuel Lutheran Church (established 1890, present church completed 1912).[1][7][8][9][10]

Pioneers

editLike most of Seattle, the Cascade Neighborhood was originally heavily forested. In the 1860s, David Denny and Thomas Mercer first claimed portions of this land. However, initial development was a bit west of Cascade, at southwest Lake Union, which became a transportation nexus and where Denny established the lake's first sawmill. By the 1880s, more mills and more cleared land led to the origin of Cascade as a residential and industrial neighborhood, tied into water transportation.[7]

Another notable pioneer was Margaret Pontius, known for her extensive work as what would now be called a foster parent. She and her husband, Rezius Pontius, lived in the neighborhood by 1885, and by 1889 had built a Queen Anne style mansion, designed by John Parkinson, along Denny Way near what is now Yale Avenue.[11]

Cascade was settled largely by Russians (some via Alaska[12]), Swedes, Norwegians, and Greeks. In 1894, the Cascade School (also designed by Parkinson[12]) opened and the neighborhood acquired a name. As the neighborhood grew, the school expanded in 1904 and 1908.[7] Cascade businesses in this era included sawmills, shingle mills, and boat yards along the lake, as well as cabinetry and furniture shops, grocery stores, laundries, and boarding houses.[13]

Both landscape architect John C. Olmsted (in 1903) and city planner Virgil Bogue (in 1910–1911) believed that the neighborhood was best suited for industrial use, although Olmsted unsuccessfully proposed that there also be a small park on the lake.[7] Denny Regrade No. 1 (completed 1911) took out nearly half of Denny Hill, making Cascade more accessible from downtown Seattle.[14] The Ford plant, designed by John Graham Sr. and built in 1914, was the Ford Motor Company's first factory built west of the Mississippi River.[15] When the Lake Washington Ship Canal opened in 1917, maritime and industrial uses intensified. The area also became the center for the city's large laundries, as well as smaller machine shops.[7] Cascade-area laundries played a crucial role in Seattle labor history, with a successful fight for the 8-hour day in the years 1917 through 1918.[15]

Great Depression

editWhen the Great Depression coincided with the decline of the extractive economy in Greater Seattle, Cascade began to decline both economically and in terms of population, with its most stable remaining industries being shipbuilding and other marine activities.[7] Howard Wright General Contractors were operating out of 409 Yale Avenue N, where they are still located as of 2008. There was also a business district between the 300 and 600 blocks of Eastlake, mainly on the west side of the street, including grocery stores, a pharmacy, a meat shop, automobile repair, furniture repair, a cabinetmaker, a beauty parlor, a barbershop, several drinking establishments, and a dye works. Although no buildings remain on the east side of the street, which abuts Interstate 5, many of these west-side buildings survive. However, with the freeway cutting it off from Capitol Hill, this is much less of a business district today.[16]

Postwar period

editThe decline of the depression years was briefly arrested by World War II, as the U.S. Navy built a reserve center on the site of David Denny's former mill, just west of Cascade and Kenworth expanded a factory on Mercer Street. Decline resumed after the war, and was greatly exacerbated when the April 13, 1949 earthquake caused structural damage to the Cascade School.[7] Controversy ensued over whether or not to repair the school, but it was ultimately demolished since local businesses led by the Seattle Times desired an increasingly industrial rather than residential character neighborhood.[17] The school was replaced by a warehouse for the school district, while its playground remained as a public park.[7]

The year 1949 also saw the first seeds of the "new" Cascade Neighborhood that would emerge almost half a century later: the Washington Teachers Credit Union was established, with quarters on Eastlake Avenue. It would become the Washington School Employees Credit Union (1963), and eventually part of PEMCO Financial Services, still based in the Cascade Neighborhood as of 2008.[7]

New zoning ordinances based on the 1956 Comprehensive Plan of Seattle forbade any new residential uses in Cascade Neighborhood. The plan also recommended two new freeways through the area. On the northern edge, the Bay Freeway would cover roughly nine city blocks between Mercer and Valley Streets, with ramps connecting to the Aurora Freeway which had been constructed in 1932. The city lacked funding for the project and plans were eventually scrapped along with the R.H. Thomson Expressway. The second freeway was Interstate 5, which was constructed in 1962. More than seven blocks of residences and retail businesses on the east side of Eastlake were razed to make way for Interstate 5. The freeway cut Cascade off entirely from neighboring Capitol Hill.[7] Previously they had been tied together by multiple streets and stairways.[18][19] (The upper half-block of the E. Republican Street Stairway or Republican Hill Climb east of Melrose Ave E. remains east of the freeway, and has status as a city landmark; it once extended two blocks farther, down to Eastlake Ave E.[20][21]) Currently, the only remaining direct route between the two is Denny Way at the south border of the neighborhood.[22]

1960s

editThe Seattle Times Building had been built in 1930 just west of Fairview Avenue.The Seattle Times;[23] in the 1960s, the Times purchased and razed acres of homes near its headquarters for parking lots and future development opportunities.[7] (One building they purchased was, for a time, operated as the Seattle Concert Theater, but even that was "hastily razed" in the early 1980s to "head off a landmarks designation".[24]) Karin Link remarks: "The relationship between the Seattle Times and the Cascade Neighborhood is still considered problematic."[25]

In the 1960s, the University of Washington's College of Architecture and Urban Planning described the area as "blighted".[26] The 1969 Bay Freeway plan for a proposed elevated freeway to connect Interstate 5 with Seattle Center would have cut off the neighborhood from the Lake, but was voted down in 1972. Cascade struggled on as a blue-collar residential and light industrial neighborhood.[7]

1970s

editIn the early 1970s, activists including a University of Washington student named Frank Chopp began the Cascade Shelter Project, setting up geodesic domes on vacant lots to live in. A 1975 report by Folke Nyberg and Victor Steinbrueck included Cascade as a historic residential section of Seattle,[27] and in 1977 the Housing In Cascade study by Paul Schell, then Director of Seattle Department of Community Development, recommended a "Special Review District" in Cascade.[28] However, the city council took no action on the proposal.

1980s

editAs the local economy strengthened in the late 1980s, Cascade's cheap land and central location began to attract new uses. The northwest corner of the neighborhood became the campus of the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center[7] and at the north tip of Cascade, the old City Light Steam Plant (a decommissioned electrical generation facility) became the headquarters of Zymogenetics.[29] Gentrification had begun. Although a proposal to transform a north–south corridor just west of Cascade into a 74-acre (30 ha) park was twice defeated by the voters (in 1995 and in 1996), gentrification continued apace, largely driven by tech billionaire and developer Paul Allen's Vulcan Northwest group.[7]

1990s

editTwo large changes in the south part of Cascade in the 1990s were the demolition of the old St. Demetrios Church (along with the Overall Laundry) to build the new REI flagship store, and the demolition of the 1907 wood-frame Lillian Apartments by Vulcan Northwest. The demolition was opposed by low-income housing advocates.[30]

Notable residents

editTeamsters labor leader Dave Beck grew up in and around Cascade Neighborhood, attended the Cascade School, and delivered newspapers there. He followed his mother into laundry work, which brought him into labor organizing.[15]

Among the notable residents of Cascade were cubist artist Nicolai Kuvshinoff and his wife Bertha Horne Kuvshinoff, who dubbed her ghostly style of painting "phantasism". Both are represented in the permanent collection of the Seattle Art Museum. Kuvshinoff arrived in Cascade from Russia in 1915. His father, the Rev. Vasily Kuvshinoff, brought with him icons and relics given to him by the Romanovs, which he bequeathed to St. Spiridon Orthodox Cathedral, where he officiated. Nicolai Kuvshinoff appears to have painted religious murals in the Cathedral. From 1955 to 1960 Kuvshinoff and his wife lived and worked in Paris, but they returned to Cascade, where they remained until Nicolai's death in 1997 (Bertha lived two years longer). During most of their time in Cascade, they lived in the former Rodgers Tile Company building at 117-121 Yale Ave. N, later the 911 Contemporary Arts Center and now the Feathered Friends outdoor equipment shop.[31]

Cascade Playground

editThe Cascade Playground (now also known as Cascade Park), originally the playground of the now-demolished Cascade School, has two play areas, a wide field, a picnic table, and restrooms. The park is adjacent to an active community P-Patch (allotment garden). Improvements to the Cascade Playground play areas, field, and entrance were unveiled in spring 2005, financed by the Pro Parks Levy. Sharing a city block with the playground and P-Patch is the Cascade People's Center, a volunteer organization that partners with over 100 businesses, churches, organizations, and community groups to address advocacy for social and economic justice.

By 1931, although most of this block had come to be owned by the City of Seattle or the School Board, a number of houses remained owned by individuals. By the end of 1931, however, the owners of these houses had sold out and the buildings were removed (although some basements may still be intact under the park surface). There was debate in the neighborhood over building the playground; in 1934, the pro-playground group eventually prevailed. Still, as late as 1937, the Fairview-Stewart Improvement Club was protested that the Cascade School was old and out of date, itself not worth preserving, and that the increasingly industrial and commercial neighborhood did not need a playfield.[23][32]

Between 1934 and 1939, WPA workers built a retaining wall (only part of which survive), the rest rooms at the northeast corner of the park, and a wading pool (which originally was part of a Japanese stone garden).[23][32][33][34][35]

By the 1970s, according to the Seattle Department of Neighborhoods, "the playground site was somewhat bleak and known by locals as the 'Sahara Desert'". A 1971 renovation included a mural on the retaining wall, funded by the Seattle Arts Commission and designed by Mike Love and George Shayler.[32] This was followed by another round of improvements in 2005.

Landmarks and historic sites

editSee also the listing of Landmarks and historic sites in the South Lake Union neighborhood, most of which fall within what are considered by some to be the borders of the Cascade neighborhood.

| Building or structure |

Address | Listing | Photo |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ford Assembly Plant Building Now Public Storage |

1155 Valley St. | Seattle landmark | |

| Immanuel Lutheran Church | 1215 Thomas St. | Seattle landmark NRHP |

|

| Jensen Block | 601-611 Eastlake Ave. E | Seattle landmark | |

| Lake Union Steam Plant and Hydro House Now Zymogenetics |

1179 Eastlake Ave. E | Seattle landmark | |

| New Richmond Laundry Now part of the Alley24 development |

224 Pontius Ave. N | Seattle landmark | |

| St. Spiridon Russian Orthodox Cathedral | 400 Yale Ave. N | Seattle landmark | |

| Supply Laundry Building Now part of the Stackhouse development |

1265 Republican St. | Seattle landmark NRHP |

In addition, the surviving portion of the East Republican Street Stairway that once connected Cascade to Capitol Hill is a designated Seattle landmark. However, the portion of it that remains is separated from Cascade by Interstate 5.

| Building or structure |

Address | Listing | Photo |

|---|---|---|---|

| East Republican Street Stairway | Between Melrose Ave. E and Bellevue Ave. E; Originally extended beyond Bellevue Ave. E to Eastlake Ave. E |

Seattle landmark |

References

edit- ^ a b History, Organizational Description, Boundaries, Cascade Neighborhood Council, November 1997. Accessed 6 June 2011.

- ^ Link 2004, p. 1

- ^ Alley24, A New Face for Seattle: A LEED-certified speculative development in Seattle is both environmentally and economically sustainable Archived October 6, 2011, at the Wayback Machine, Sebastian Howard, GreenSource, March 2009. Accessed 6 June 2011.

- ^ Who's built what in South Lake Union (also see map), Eric Pryne, Seattle Times. Accessed 6 June 2011.

- ^ Summary for 1206 Republican ST / Parcel ID 2467400237, Seattle Department of Neighborhoods. Accessed online 4 February 2008.

- ^ Seattle and the Orient (1900), The Times Printing Company (Seattle), p. 71.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n Louis Fiset, Seattle Neighborhoods: Cascade and South Lake Union – Thumbnail History, HistoryLink, April 9, 2001. Accessed 3 February 2008.

- ^ Dorothea Mootafes, Theodora Dracopoulos Argue, Paul Plumis, Perry Scarlatos, Peggy Falangus Tramountanas, eds., A History of Saint Demetrios Greek Orthodox Church and Her People, Saint Demetrios Greek Orthodox Church, 2007 (1996). p. 65, 73, 128–131.

- ^ Summary for 1310 Harrison ST / Parcel ID 6847700030, Seattle Department of Neighborhoods. Accessed 3 February 2008. This is a description of the Sts. Cyril and Methodius Education Building adjacent to St. Spiridon, and mentions the construction date of the latter.

- ^ Walt Crowley, National Trust Guide Seattle: America's Guide for Architecture and History (1998), John Wiley and Sons, ISBN 0-471-18044-0, p.167.

- ^ Link 2004, p. 4

- ^ a b Link 2004, p. 5

- ^ Link 2004, p. 7

- ^ Link 2004, p. 8

- ^ a b c Link 2004, p. 9

- ^ Link 2004, pp. 13–14

- ^ Link 2004, p. 14

- ^ Insurance Maps of Seattle, Washington, Volume 4, Sanborn Map Company, 1917–June 1950, sheets 441, 442, 451, 468, 470, 471, 484, 485, 486; especially 471, 486.

- ^ Link 2004, pp. 14–15

- ^ Landmarks Alphabetical Listing for E Archived 2011-07-21 at the Wayback Machine, Seattle Department of Neighborhoods. Retrieved on 2008-02-06.

- ^ Paul Dorpat, Seattle Neighborhoods: Republican Hill Climb between Capitol Hill and the Cascade Neighborhood completed on February 25, 1910, HistoryLink, 6 May 2001. Retrieved on 2008-02-06.

- ^ Map NN-1230-L, Seattle City Clerk's Neighborhood Map Atlas, Seattle City Clerk's Office. Retrieved 6 February 2008.

- ^ a b c Link 2004, p. 12

- ^ Eric Scigliano, Publisher's prerogative Archived 2011-05-16 at the Wayback Machine, Seattle Weekly, 20 June 2001. Accessed online 6 February 2008.

- ^ Link 2004, p. 16

- ^ Link 2004, p. 15

- ^ Folke Nyberg and Victor Steinbrueck, An Urban Resource Inventory for Seattle (Seattle: Historic Seattle Preservation and Development Authority, 1975). Retrieved on 2011-06-04 from http://www.historicseattle.org/resources/neighborhoodinventories.aspx Archived 2011-09-28 at the Wayback Machine .

- ^ Housing in Cascade : Cascade Neighborhood Study prepared for the Seattle Department of Community Development / Richardson Associates, Northwest American, Northwest Environmental Technology Laboratories. Available from UW Libraries, HT177.S6 H69.

- ^ "ZymoGenetics' Steam Plant Facility: A Brief History. Zymogenetics". Archived from the original on 2008-05-09. Retrieved 2008-02-09..

- ^ Link 2004, pp. 16–17

- ^ Summary for 117 Yale AVE / Parcel ID 6849700075, Seattle Department of Neighborhoods. Accessed 5 February 2008.

- ^ a b c Summary for Harrison-Thomas St, Minor-Pontius AVE / Parcel ID 2467400335 (Cascade Playground). Seattle Department of Neighborhoods. Retrieved on 2008-02-06 from http://web1.seattle.gov/dpd/historicalsite/QueryResult.aspx?ID=131518019.

- ^ Summary for Harrison-Thomas St, Minor-Pontius AVE / Parcel ID 2467400335 (Cascade Playground Wading Pool and Garden), Seattle Department of Neighborhoods. Accessed online 6 February 2008.

- ^ Summary for Harrison-Thomas St, Minor-Pontius AVE / Parcel ID 2467400335 (Cascade Playground Retaining Walls), Seattle Department of Neighborhoods. Accessed online 6 February 2008.

- ^ Summary for Harrison-Thomas St, Minor-Pontius AVE / Parcel ID 2467400335 (Cascade Playground Comfort Station), Seattle Department of Neighborhoods. Accessed online 6 February 2008.

Additional references

edit- Fiset, Louis (9 April 2001). Seattle Neighborhoods: Cascade and South Lake Union – Thumbnail History. HistoryLink.org Essay 3178, April 9, 2001. Retrieved on 2007-09-09 from Seattle Neighborhoods: Cascade and South Lake Union -- Thumbnail History.

- Link, Karin (2004-01-12), 2003 Cascade Historic Survey: Buildings, Objects & Artifacts, Revised Version (PDF), Seattle Department of Neighborhoods, archived from the original (PDF) on 2008-04-10, retrieved 2008-02-06. This document discusses many individual buildings, past and present, as well as the people of the neighborhood at various times in its history. It also has an extensive bibliography.

External links

edit- Media related to Cascade, Seattle, Washington at Wikimedia Commons