Coronary ischemia, myocardial ischemia,[1] or cardiac ischemia,[2] is a medical term for abnormally reduced blood flow in the coronary circulation through the coronary arteries.[3] Coronary ischemia is linked to heart disease, and heart attacks.[4] Coronary arteries deliver oxygen-rich blood to the heart muscle.[5] Reduced blood flow to the heart associated with coronary ischemia can result in inadequate oxygen supply to the heart muscle.[6] When oxygen supply to the heart is unable to keep up with oxygen demand from the muscle, the result is the characteristic symptoms of coronary ischemia, the most common of which is chest pain.[6] Chest pain due to coronary ischemia commonly radiates to the arm or neck.[7] Certain individuals such as women, diabetics, and the elderly may present with more varied symptoms.[8] If blood flow through the coronary arteries is stopped completely, cardiac muscle cells may die, known as a myocardial infarction, or heart attack.[9]

| Coronary ischemia | |

|---|---|

| Other names | myocardial ischemia, cardiac ischemia |

| |

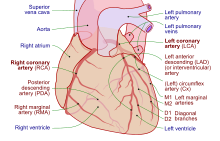

| Coronary arteries of the human heart | |

| Specialty | Cardiology |

Coronary artery disease (CAD) is the most common cause of coronary ischemia.[7] Coronary ischemia and coronary artery disease are contributors to the development of heart failure over time.[10] Diagnosis of coronary ischemia is achieved by an attaining a medical history and physical examination in addition to other tests such as electrocardiography (ECG), stress testing, and coronary angiography.[11] Treatment is aimed toward preventing future adverse events and relieving symptoms.[12] Beneficial lifestyle modifications include smoking cessation, a heart healthy diet, and regular exercise.[13] Medications such as nitrates and beta-blockers may be useful for reducing the symptoms of coronary ischemia.[6] In refractory cases, invasive procedures such as percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) or coronary artery bypass graft (CABG) may be performed to relieve coronary ischemia.[14]

Recently, evidence has been found that ischemia can also occur without coronary obstruction (a conditional known as INOCA - ischemia with no obstructed arteries).[1] Other studies have found that Long COVID or post acute COVID syndrome can also be associated with myocardial ischemia.[15] Treatment for both conditions is similar to treatment for ischemia caused by CAD.[1][15]

INOCA

editINOCA is cardiac ischemia with no coronary artery obstruction.[16] Approximately 3-4 million people have been diagnosed with this condition; with female diagnosis prevalent. Risk factors include female sex, advanced age, smoking, hyperlipidemia, inflammatory disease, diabetes and glucose intolerance.[17] Diagnosis of INOCA can begin with non-invasive testing including PET with myocardial perfusion imaging (MPI) or stress cardiovascular magnetic resonance (CMR) imaging. However, final diagnosis must be made with cardiac angiography to confirm the absence of occlusion.[18]

Ischemia Involving SARS-CoV-2

editData involving cardiac ischemia resulting from post acute COVID syndrome (or Long COVID) is evolving. Various studies have been combined to show a significant percentage of patients presenting with myocardial ischemia post COVID infection (infection requiring hospitalization) with no documented prior history of coronary disease. Vaccination (with 2 doses) has been shown to decrease the risk of Long COVID in recent studies.[15]

Signs and symptoms

editA key symptom of coronary ischemia is chest pain or pressure, known as angina pectoris.[4] Angina may present typically with classic symptoms or atypically with symptoms less often associated with heart disease.[19] Atypical presentations are more common in women, diabetics, and elderly individuals.[8] Angina may be stable or unstable. Unstable angina is most often associated with emergent, acute coronary syndromes.[20]

Angina is typically located below the sternum.[4] Individuals experiencing angina characterize the pain in different ways, but the pain is usually described as crushing, squeezing, or burning.[7] Symptoms may worsen over the course of several minutes.[4] Typical angina is aggravated by physical activity or emotional stress and is relieved by rest or nitroglycerin.[4] The pain may radiate to other parts of the body, most commonly the left arm or neck.[7] In some individuals, the pain may be less severe and present as pressure or numbness.[7] Less commonly, the pain may radiate to both arms, the jaw, or to the back.[20]

Atypical

editWomen, diabetic individuals, and elderly individuals are more likely to present with atypical symptoms other than chest pain.[8] Women may present with back pain, shortness of breath, heartburn, nausea, and vomiting.[19] Heart disease in women goes undetected prior to a major cardiac event in up to 60% of cases.[19] Among women who experience a heart attack, many do not have any prior chest pain.[19] Due to alterations in sensory pathways, diabetic and elderly individuals also may present without any chest pain and may have atypical symptoms similar to those seen in women.[8] This type of ischemia is also known as silent ischemia.[21][22][23][24]

Causes

editCoronary artery disease (CAD) occurs when fatty substances, known as plaques, adhere to the walls of coronary arteries supplying the heart, narrowing them and constricting blood flow, a process known as atherosclerosis, the most common cause of coronary ischemia.[25] Angina may start to occur when the vessel is 70% occluded.[9] Lack of oxygen may also result in a myocardial infarction (heart attack).[26] CAD can be contracted over time. Risk factors include a family history of CAD, smoking, high blood pressure, diabetes, obesity, inactive lifestyle, mental stress and high cholesterol.[26][27] Angina can also occur due to spasm of the coronary arteries, even in individuals without atherosclerosis.[28] In coronary artery spasm, the vessel constricts to limit blood flow through the artery, causing a decrease in oxygen supply to the heart, although the mechanisms for this phenomenon are not fully understood.[28]

Natural course

editCoronary ischemia can have serious consequences if it is not treated. Plaques in the walls of the coronary arteries can rupture, resulting in occlusion of the artery and deprivation of blood flow and oxygen to the heart muscle, resulting in cardiac cell death.[9] This is known as myocardial infarction.[9] A heart attack can cause arrhythmias, as well as permanent damage to the heart muscle.[25] Coronary ischemia resulting from coronary artery disease also increases the risk of developing heart failure.[10] Most cases of heart failure result from underlying coronary artery disease.[10] A myocardial infarction carries a greater than five-fold increase in relative risk for developing heart failure.[10]

Diagnosis

editIf coronary ischemia is suspected, a series of tests will be undertaken for confirmation. The most common tests used are an electrocardiogram, an exercise stress test, and a coronary angiography.[29] A variety of laboratory tests may be ordered. An important laboratory test to determine if myocardial damage has occurred is a cardiac troponin value.[20] A medical history will be taken, including queries about past incidence of chest pain or shortness of breath. The duration and frequency of symptoms will be noted as will any measures taken to relieve the symptoms.[29]

Electrocardiogram

editA resting electrocardiogram (EKG) is an early step in the diagnostic process.[11] An electrocardiogram (EKG) involves the use of electrodes that are placed on the arms, chest, and legs.[29] These sensors detect any abnormal rhythms that the heart may be producing. This test is painless and it helps detect insufficient blood flow to the heart.[29] An EKG can also detect damage that has been done in the past to the heart.[30] This test can also detect any thickening in the walls of the left ventricles as well as any defects in the electrical impulses of the heart.[29] It is quick and provides the Physician with the P/PR, Heart Rate, QRS, QT/QTcF, P/QRS/T, and axis results.[31][32]

Exercise stress electrocardiogram

editA cardiac stress test, puts stress on the heart through exercise. A series of exercises to measure the tolerance for stress on the heart will be carried out. This test uses an EKG to detect the electrical impulses of the heart during physical exertion.[29]

A treadmill or exercise bike will be used. The incline or resistance of the bike are steadily increased until the target heart rate for the person's age and weight is reached.[29] However, an exercise stress test is not always accurate in determining the presence of a blockage in the arteries.[11] Women and those who are young may show abnormalities on their test even though no signs of coronary ischemia or CAD are present.[29] Harmless arrhythmias present at baseline may distort the results.[11] Diagnosis of coronary artery disease is missed in 37% of men and 18% of women with a negative test.[33] However, those patients who are able to complete the test are at lower risk of future cardiac events.[11]

Stress echocardiography

editStress echocardiography is very commonly used in assessing for ischemia resulting from coronary artery disease. It can be performed exercising, preferably with a bicycle that allows the patient to exercise while lying flat, which allows for imaging throughout the entire testing period.[33] While the patient is exercising, images of the heart in motion are generated.[34] Ischemia can be detected by visualizing abnormalities in the movement of the heart and the thickness of the heart wall during exercise.[34]

Some people may be unable to exercise in order to achieve a sufficient heart rate for a useful test. In these cases, high-dose dobutamine may be used to chemically increase heart rate.[11] If dobutamine is insufficient for this purpose, atropine be added to reach goal heart rate.[11] Dipyridamole is an alternative to dobutamine but it is less effective in detecting abnormalities.[34] While exercise echocardiograms are more effective in detecting coronary artery disease, all forms of stress echocardiograms are more effective than exercise EKG in detecting coronary ischemia secondary to coronary artery disease.[11] If stress echocardiography is normal, risk of future adverse cardiac events is low enough that invasive coronary angiography is not needed.[34]

Coronary angiography

editA coronary angiography is performed after a stress test or EKG shows abnormal results.[35] This test is very important in finding where the blockages are in the arteries.[29] This test helps determine if an angioplasty or bypass surgery is needed.[36] Coronary angiography should only be performed if a patient is a willing to undergo a coronary revascularization procedure.[37]

During this test the doctor makes a small incision in the patient's groin or arm and inserts a catheter.[35] The catheter has a very small video camera on the end of it so that the doctor can find the arteries.[29] Once they have found the arteries, they inject a dye in them so that they can detect any blockages in the arteries.[35] The dye is able to be seen on a special x-ray machine.[29]

Treatment

editCoronary ischemia can be treated but not cured.[38] By changing lifestyle, further blockages can be prevented.[39] A change in lifestyle, mixed with prescribed medication, can improve health.[13] In some cases, coronary revascularization procedures may be used.[14]

Smoking cessation

editTobacco smoking is a clear risk factor for development of coronary artery disease.[13] Exposure to second hand smoke also has clear cardiovascular risks.[13] Tobacco smokers have higher levels of cholesterol and triglycerides which are risk factors for development of coronary artery disease.[40] Smoking has been shown in numerous studies to accelerate atherosclerosis by several years.[39] A study showed that those who quit smoking reduced their risk of being hospitalized over the next two years.[38] The benefits of smoking cessation are greater the longer an individual has been abstinent from tobacco.[39] After two years of smoking cessation, risk of heart attack can be cut in half.[40] Smoking cessation has a significant mortality benefit regardless of age.[13] Nicotine replacement therapy, bupropion, and varenicline are safe therapies that improve the likelihood of smoking cessation.[40]

Healthy diet

editA healthy diet is a very important factor in preventing coronary ischemia or coronary artery disease.[38] A heart-healthy diet is low in saturated fat and cholesterol and high in fruits, vegetables, and whole grains.[39] Recent studies have shown that there is an inverse correlation between increased fruit and vegetable intake and the risk of CAD.[13] A mortality benefit has been seen in individuals with higher intake of whole grains.[41] These food choices can reduce the risk of a heart attack or any other congestive heart failure event.[38] These foods may also slow further growth of plaques in the coronary arteries and reduce further ischemia.[39]

Physical activity

editBy increasing physical activity, it is possible to manage body weight, reduce blood pressure, and relieve stress.[38] Moderate intensity exercise of 30–60 minutes per day for 5–7 days per week is recommended.[13] Moderate intensity exercise is defined as exercise that increases heart rate to 55-74% of maximum heart rate.[42] High intensity exercise increasing the heart rate to 70-100% of maximum heart rate for shorter intervals is at least as effective, and this type of exercise may increase oxygen uptake by the heart compared to moderate intensity exercise.[43] Per the Center for Disease Control, an estimate of maximum heart rate for an individual can be calculated by subtracting age from 220.[44] Exercising this way can reduce the risk of getting heart disease or coronary ischemia.[38]

Medication-based therapy

editMedication-based therapy for coronary ischemia should be focused on reducing the likelihood of future adverse cardiac events and treating symptoms of coronary ischemia such as angina.[45] Key medications with strong evidence of benefit include aspirin, or alternatively clopidogrel.[45] These medications help to prevent clots in the coronary artery and the occlusion which can lead to a heart attack.[46] Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors are indicated in individuals with diabetes, kidney disease, and hypertension.[45] Statin medications help to reduce cholesterol and plaque formation and may even contribute to plaque regression.[47]

Other medications may be used to reduce the symptoms of coronary ischemia, particularly angina. Long and short acting nitrates are one option for reducing anginal pain.[6] Nitrates reduce the symptoms of angina by dilating blood vessels around the heart, which increases oxygen-rich blood supply to the muscle cells of the heart.[48] Veins are also dilated, which reduces return of blood to the heart, easing strain on the heart muscle.[48] Short-acting nitrates can be taken upon the onset of symptoms and should provide relief within minutes.[6] Nitroglycerin is the most common short-acting nitrate and it is applied under the tongue.[6] Long acting nitrates are taken 2-3 times per day and can be used to prevent angina.[6] Beta-blockers may also be used to reduce the incidence of chronic angina.[6] Beta-blockers prevent episodes of angina by reducing heart rate and reducing the strength of contraction of the heart, which lowers oxygen demand in the heart.[6]

Coronary revascularization

editIn individuals with symptoms that are not well controlled with medical and lifestyle therapy there are invasive options available including percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) and coronary artery bypass graft (CABG).[37] PCI involves placing a stent to relieve coronary artery blockages.[12] CABG involves grafting new blood vessels to provide a new route for blood flow around the blocked vessel.[12] Choice of treatment is based on the number of coronary vessels with blockages, which vessels are effected, and the medical history of the patient.[37] There is not sufficient evidence to suggest that PCI or CABG provides a mortality benefit in individuals with stable coronary ischemia.[14] More recently, research has been investigating the short- and long-term efficacy of Hybrid Coronary Revascularization (HCR), a combination of both PCI and CABG. Some research supports that HCR is a stronger option compared to PCI or CABG alone for multivessel coronary artery disease because HCR is better at lowering the risk of short-term adverse cardiac/vascular events.[49]

References

edit- ^ a b c "Myocardial ischemia". Mayo Clinic. Retrieved 2019-11-29.

- ^ Potochny, Evy. "Cardiac Ischemia Symptoms." LiveStrong. Demand Media, 9 March 2010. Web. 6 Nov. 2010.

- ^ "Sacred Heart Medical Center. Spokane, Washington. Coronary Ischemia". Shmc.org. Archived from the original on 2009-05-01. Retrieved 2008-12-28.

- ^ a b c d e Kloner RA, Chaitman B (May 2017). "Angina and Its Management". Journal of Cardiovascular Pharmacology and Therapeutics. 22 (3): 199–209. doi:10.1177/1074248416679733. PMID 28196437. S2CID 4074303.

- ^ "Anatomy and Function of the Coronary Arteries". www.hopkinsmedicine.org. 23 November 2020. Retrieved 2020-11-24.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Palaniswamy C, Aronow WS (September 2011). "Treatment of stable angina pectoris". American Journal of Therapeutics. 18 (5): e138–e152. doi:10.1097/MJT.0b013e3181f2ab9d. PMID 20861717.

- ^ a b c d e Shao C, Wang J, Tian J, Tang YD (2020). "Coronary Artery Disease: From Mechanism to Clinical Practice". Coronary Artery Disease: Therapeutics and Drug Discovery. Advances in Experimental Medicine and Biology. Vol. 1177. pp. 1–36. doi:10.1007/978-981-15-2517-9_1. ISBN 978-981-15-2516-2. PMID 32246442. S2CID 214786596.

- ^ a b c d Kones R (August 2010). "Recent advances in the management of chronic stable angina I: approach to the patient, diagnosis, pathophysiology, risk stratification, and gender disparities". Vascular Health and Risk Management. 6: 635–656. doi:10.2147/vhrm.s7564. PMC 2922325. PMID 20730020.

- ^ a b c d Reed GW, Rossi JE, Cannon CP (January 2017). "Acute myocardial infarction". Lancet. 389 (10065): 197–210. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(16)30677-8. PMID 27502078. S2CID 33523662.

- ^ a b c d Lala A, Desai AS (April 2014). "The role of coronary artery disease in heart failure". Heart Failure Clinics. 10 (2): 353–365. doi:10.1016/j.hfc.2013.10.002. PMID 24656111.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Mordi IR, Badar AA, Irving RJ, Weir-McCall JR, Houston JG, Lang CC (2017). "Efficacy of noninvasive cardiac imaging tests in diagnosis and management of stable coronary artery disease". Vascular Health and Risk Management. 13: 427–437. doi:10.2147/VHRM.S106838. PMC 5701553. PMID 29200864.

- ^ a b c Doenst T, Haverich A, Serruys P, Bonow RO, Kappetein P, Falk V, et al. (March 2019). "PCI and CABG for Treating Stable Coronary Artery Disease: JACC Review Topic of the Week". Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 73 (8): 964–976. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2018.11.053. PMID 30819365. S2CID 73467926.

- ^ a b c d e f g Jia S, Liu Y, Yuan J (2020). "Evidence in Guidelines for Treatment of Coronary Artery Disease". Coronary Artery Disease: Therapeutics and Drug Discovery. Advances in Experimental Medicine and Biology. Vol. 1177. pp. 37–73. doi:10.1007/978-981-15-2517-9_2. ISBN 978-981-15-2516-2. PMID 32246443. S2CID 214786177.

- ^ a b c Braun MM, Stevens WA, Barstow CH (March 2018). "Stable Coronary Artery Disease: Treatment". American Family Physician. 97 (6): 376–384. PMID 29671538.

- ^ a b c Mohammad, Khan O.; Lin, Andrew; Rodriguez, Jose B. Cruz (December 2022). "Cardiac Manifestations of Post-Acute COVID-19 Infection". Current Cardiology Reports. 24 (12): 1775–1783. doi:10.1007/s11886-022-01793-3. ISSN 1523-3782. PMC 9628458. PMID 36322364.

- ^ Sucato V, Madaudo C, Galassi AR (October 2024). "The ANOCA/INOCA Dilemma Considering the 2024 ESC Guidelines on Chronic Coronary Syndromes". J Cardiovasc Dev Dis. 11 (10): 302. doi:10.3390/jcdd11100302. PMC 11508505. PMID 39452273.

- ^ Mone P, Lombardi A, Salemme L, Cioppa A, Popusoi G, Varzideh F, Pansini A, Jankauskas SS, Forzano I, Avvisato R, Wang X, Tesorio T, Santulli G (February 2023). "Stress Hyperglycemia Drives the Risk of Hospitalization for Chest Pain in Patients With Ischemia and Nonobstructive Coronary Arteries (INOCA)". Diabetes Care. 46 (2): 450–454. doi:10.2337/dc22-0783. PMC 9887616. PMID 36478189.

- ^ Odanović N, Schwann AN, Zhang Z, Kapadia SS, Kunnirickal SJ, Parise H, Tirziu D, Ilic I, Lansky AJ, Pietras CG, Shah SM (October 2024). "Long-term outcomes of ischaemia with no obstructive coronary artery disease (INOCA): a systematic review and meta-analysis". Open Heart. 11 (2): e002852. doi:10.1136/openhrt-2024-002852. PMC 11448144. PMID 39353703.

- ^ a b c d Leuzzi C, Modena MG (July 2010). "Coronary artery disease: clinical presentation, diagnosis and prognosis in women". Nutrition, Metabolism, and Cardiovascular Diseases. 20 (6): 426–435. doi:10.1016/j.numecd.2010.02.013. PMID 20591634.

- ^ a b c Foreman RD, Garrett KM, Blair RW (April 2015). "Mechanisms of cardiac pain". Comprehensive Physiology. 5 (2): 929–960. doi:10.1002/cphy.c140032. ISBN 9780470650714. PMID 25880519.

- ^ "Silent Ischemia - Myocardial Ischemia Without Angina | Beaumont | Beaumont Health". www.beaumont.org. Retrieved 2022-05-28.

- ^ "Silent Ischemia and Ischemic Heart Disease". www.heart.org. Retrieved 2022-05-28.

- ^ Cohn PF, Fox KM, Daly C (September 2003). "Silent myocardial ischemia". Circulation. 108 (10): 1263–1277. doi:10.1161/01.CIR.0000088001.59265.EE. PMID 12963683. S2CID 21363320.

- ^ Deedwania PC. "Silent myocardial ischemia: Epidemiology, diagnosis, treatment, and prognosis". www.uptodate.com. Retrieved 2022-05-28.

- ^ a b ["Ischemia." Ischemic Heart Disease. Ischemic Heart Disease, n.d. Web. 6 Nov. 2010.]

- ^ a b ""Coronary Artery Disease". Adult Health Advisor. Tufts Medical Center. July 2009.

- ^ Vaccarino V, Sullivan S, Hammadah M, Wilmot K, Al Mheid I, Ramadan R, et al. (February 2018). "Mental Stress-Induced-Myocardial Ischemia in Young Patients With Recent Myocardial Infarction: Sex Differences and Mechanisms". Circulation. 137 (8): 794–805. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.117.030849. PMC 5822741. PMID 29459465.

- ^ a b Picard F, Sayah N, Spagnoli V, Adjedj J, Varenne O (January 2019). "Vasospastic angina: A literature review of current evidence". Archives of Cardiovascular Diseases. 112 (1): 44–55. doi:10.1016/j.acvd.2018.08.002. PMID 30197243.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Gerstenblith G, Margolis S (January 2008). "Diagnosis of Coronary Heart Disease". Coronary Heart Disease. Baltimore, Md: Johns Hopkins Medical Institutions. pp. 18–25. ISBN 978-1-933087-60-3.

- ^ Horan LG, Flowers NC, Johnson JC (March 1971). "Significance of the diagnostic Q wave of myocardial infarction". Circulation. 43 (3): 428–436. doi:10.1161/01.cir.43.3.428. PMID 5544988. S2CID 1313759.

- ^ Surawicz B, Childers R, Deal BJ, Gettes LS, Bailey JJ, Gorgels A, et al. (March 2009). "AHA/ACCF/HRS recommendations for the standardization and interpretation of the electrocardiogram: part III: intraventricular conduction disturbances: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association Electrocardiography and Arrhythmias Committee, Council on Clinical Cardiology; the American College of Cardiology Foundation; and the Heart Rhythm Society. Endorsed by the International Society for Computerized Electrocardiology". Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 53 (11): 976–981. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2008.12.013. PMID 19281930. S2CID 205528796.

- ^ Wagner GS, Macfarlane P, Wellens H, Josephson M, Gorgels A, Mirvis DM, et al. (March 2009). "AHA/ACCF/HRS recommendations for the standardization and interpretation of the electrocardiogram: part VI: acute ischemia/infarction: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association Electrocardiography and Arrhythmias Committee, Council on Clinical Cardiology; the American College of Cardiology Foundation; and the Heart Rhythm Society. Endorsed by the International Society for Computerized Electrocardiology". Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 53 (11): 1003–1011. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2008.12.016. PMID 19281933. S2CID 29176178.

- ^ a b Banerjee A, Newman DR, Van den Bruel A, Heneghan C (May 2012). "Diagnostic accuracy of exercise stress testing for coronary artery disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis of prospective studies". International Journal of Clinical Practice. 66 (5): 477–492. doi:10.1111/j.1742-1241.2012.02900.x. PMID 22512607. S2CID 41178135.

- ^ a b c d Gurunathan S, Senior R (October 2017). "Stress Echocardiography in Stable Coronary Artery Disease". Current Cardiology Reports. 19 (12): 121. doi:10.1007/s11886-017-0935-x. PMID 29046974. S2CID 45946377.

- ^ a b c "Coronary Angiography | NHLBI, NIH". www.nhlbi.nih.gov. Retrieved 2020-11-25.

- ^ Pyxaras SA, Wijns W, Reiber JH, Bax JJ (June 2018). "Invasive assessment of coronary artery disease". Journal of Nuclear Cardiology. 25 (3): 860–871. doi:10.1007/s12350-017-1050-5. PMID 28849416. S2CID 213359.

- ^ a b c Fihn SD, Blankenship JC, Alexander KP, Bittl JA, Byrne JG, Fletcher BJ, et al. (November 2014). "2014 ACC/AHA/AATS/PCNA/SCAI/STS focused update of the guideline for the diagnosis and management of patients with stable ischemic heart disease: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines, and the American Association for Thoracic Surgery, Preventive Cardiovascular Nurses Association, Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions, and Society of Thoracic Surgeons". Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 64 (18): 1929–1949. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2014.07.017. PMID 25077860.

- ^ a b c d e f Gerstenblith G, Margolis S (January 2008). Lifestyle Measures to Prevent and Treat Coronary Artery Disease. Hopkins Heart (Report). pp. 25–36.

- ^ a b c d e Parsons C, Agasthi P, Mookadam F, Arsanjani R (November 2018). "Reversal of coronary atherosclerosis: Role of life style and medical management". Trends in Cardiovascular Medicine. 28 (8): 524–531. doi:10.1016/j.tcm.2018.05.002. PMID 29807666. S2CID 44073771.

- ^ a b c Pipe AL, Papadakis S, Reid RD (March 2010). "The role of smoking cessation in the prevention of coronary artery disease". Current Atherosclerosis Reports. 12 (2): 145–150. doi:10.1007/s11883-010-0105-8. PMID 20425251. S2CID 1087175.

- ^ Zong G, Gao A, Hu FB, Sun Q (June 2016). "Whole Grain Intake and Mortality From All Causes, Cardiovascular Disease, and Cancer: A Meta-Analysis of Prospective Cohort Studies". Circulation. 133 (24): 2370–2380. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.115.021101. PMC 4910651. PMID 27297341.

- ^ Boutcher YN, Boutcher SH (March 2017). "Exercise intensity and hypertension: what's new?". Journal of Human Hypertension. 31 (3): 157–164. doi:10.1038/jhh.2016.62. PMID 27604656. S2CID 3750952.

- ^ Gomes-Neto M, Durães AR, Reis HF, Neves VR, Martinez BP, Carvalho VO (November 2017). "High-intensity interval training versus moderate-intensity continuous training on exercise capacity and quality of life in patients with coronary artery disease: A systematic review and meta-analysis". European Journal of Preventive Cardiology. 24 (16): 1696–1707. doi:10.1177/2047487317728370. PMID 28825321. S2CID 5478282.

- ^ "Target Heart Rate and Estimated Maximum Heart Rate | Physical Activity | CDC". www.cdc.gov. 2020-10-14. Retrieved 2020-11-24.

- ^ a b c Qaseem A, Fihn SD, Dallas P, Williams S, Owens DK, Shekelle P (November 2012). "Management of stable ischemic heart disease: summary of a clinical practice guideline from the American College of Physicians/American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association/American Association for Thoracic Surgery/Preventive Cardiovascular Nurses Association/Society of Thoracic Surgeons". Annals of Internal Medicine. 157 (10): 735–743. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-157-10-201211200-00011. PMID 23165665.

- ^ Malakar AK, Choudhury D, Halder B, Paul P, Uddin A, Chakraborty S (August 2019). "A review on coronary artery disease, its risk factors, and therapeutics". Journal of Cellular Physiology. 234 (10): 16812–16823. doi:10.1002/jcp.28350. PMID 30790284. S2CID 73470073.

- ^ Puri R, Nissen SE, Nicholls SJ (August 2015). "Statin-induced coronary artery disease regression rates differ in men and women". Current Opinion in Lipidology. 26 (4): 276–281. doi:10.1097/MOL.0000000000000195. PMID 26132419. S2CID 24615474.

- ^ a b Todd PA, Goa KL, Langtry HD (December 1990). "Transdermal nitroglycerin (glyceryl trinitrate). A review of its pharmacology and therapeutic use". Drugs. 40 (6): 880–902. doi:10.2165/00003495-199040060-00009. PMID 2127741. S2CID 46961874.

- ^ Wang C, Li P, Zhang F, Li J, Kong Q (November 2021). "Is hybrid coronary revascularization really beneficial in the long term?". European Journal of Cardio-Thoracic Surgery. 60 (5): 1158–1166. doi:10.1093/ejcts/ezab161. PMID 34151954.