The Japanese white crucian carp, also known as Japanese carp, white crucian carp, or gengoro-buna (Carassius cuvieri), is a species of freshwater fish in the carp family (family Cyprinidae). It is found in Japan and, as an introduced species, in several other countries in Asia.[2] This fish is closely related to the commonly known goldfish.

| Japanese white crucian carp | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Actinopterygii |

| Order: | Cypriniformes |

| Family: | Cyprinidae |

| Subfamily: | Cyprininae |

| Genus: | Carassius |

| Species: | C. cuvieri

|

| Binomial name | |

| Carassius cuvieri | |

| Synonyms [1] | |

| |

Description

editThis is a medium fish, growing up to 50 cm, with a broad head and a blunt snout. The lips are fleshy, and lacking barbels. The body is deep and laterally compressed, with a distinctly humped back. The scales are large and cycloid in shape, with a complete lateral line. Serration is present on the last ray of the dorsal and anal fins, and the caudal fin is forked.[2]

Taxonomy

editThe Japanese white crucian carp was formerly considered a subspecies of wild goldfish, and was classified as C. auratus cuvieri. It has now been elevated to species rank, however some authors are in disagreement.[3] Genetic studies using mitochondrial DNA indicate that this species diverged from the ancestral form approximately one million years ago, during the early Pleistocene.[3]

The original wild species unique to Lake Biwa is called gengorō-buna (ゲンゴロウブナ (源五郎鮒)).[4][5] Fossil pharyngeal teeth that appear to belong to ancestral form of Japanese white crucian carp have been found in the upper part of the Katata Formation, derived from sediment layers of the former Paleo-lake Katata, on the southwest shore of Lake Biwa.[6]

Distribution and habitat

editHistorically, the Japanese white crucian carp was endemic to Lake Biwa,[5] as well as the connected Yodo River system,[7] in Japan. However, it has been introduced to Taiwan[2] and Korea. In South Korea initial introductions were the result of stocking by government agencies. Subsequently, the species has also been spread through the Buddhist practice of "life releasing", in which animals destined for slaughter are instead released into the wild.[8]

Possession of this species without a permit is prohibited in the state of Vermont.[9]

It is a freshwater fish, preferring still or slow moving waters, and occurs at depths up to 20 meters. Typical habitats include lakes, canals, and backwaters.[2]

Feeding, diet, and related information

editAn omnivorous species, Japanese white crucian carp feed on a variety foods, including algae, phytoplankton, macrophytes, and invertebrates, such as insects and crustaceans.[2] During the larval stage, zooplankton comprise the primary food source. Upon reaching 1.8 cm the young fish form schools and move offshore to feed on phytoplankton. Phytoplankton remains the primary food source through adulthood.[5] This is reflected in the unique structure of their pharyngeal teeth, which are specialized to feed on phytoplankton.[6]

Reproduction

editSpawning occurs from April to June,[5] and takes place in areas of aquatic vegetation, including reed beds. Some individuals will migrate into connected satellite water bodies in order to spawn.[10] Larvae and juveniles tend to remain close to spawning areas.[10]

Importance to humans

editJapanese white crucian carp, as well as other crucian carp species, are the target of an established local fishing industry on Lake Biwa.[6] It is being used as a substitute for the depleted stock of nigoro-buna in the preparation of the intense-smelling fermented local dish funazushi due to the nigoro-buna's falling numbers.[5]

A larger cultivated variant, with a taller body depth known as hera-buna (ヘラブナ), was developed from the original species, cultured in the Osaka area and now released in many areas of Japan for sport fishing. It is enjoyed for catch-and-release.[11] It is a major carp species in Chinese aquaculture, where it is raised for food.[12][13]

This species has been identified as an intermediate host of Clinostomum complanatum, a parasitic fluke capable of infecting humans.[14]

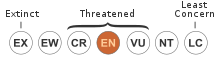

Conservation status

editThe wild species in Lake Biwa is listed as an endangered species in the Japanese Red Data Book.[4][5] Factors in its decline include water pollution, invasive species, and overfishing.[10]

References

edit- ^ a b Froese, Rainer; Pauly, Daniel (eds.). "Carassius cuvieri". FishBase. may 2018 version.

- ^ a b c d e Shao, Kwang-Tsao. "Carassius cuvieri". The Fish Database of Taiwan. WWW Web electronic publication. Version 2009/1. Retrieved 28 November 2012.

- ^ a b Apalikova, O.; Podlesnykh, A.; Kukhlesky, A.; Guohua, S.; Brykov, V. (2011). "Phylogenetic relationships of silver crucian carp Carassius auratus gibelio, C. auratus cuvieri, crucian carp Carassius carassius, and common carp Cyprinus carpio as inferred from mitochondrial DNA variation". Russian Journal of Genetics. 47 (3): 322–331. doi:10.1134/S1022795411020025.

- ^ a b Search system of Japanese Red Data Archived 2014-06-04 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ a b c d e f Kunimune, Yoshio; Mitsunaga, Yasushi; Komeyama, Kazuyoshi; Matsuda, Masanari; Kobayashi, Toru; Takagi, Tsutomu; Yamane, Takeshi (2011). "Seasonal distribution of adult crucian carp nigorobuna Carassius auratus grandoculis and gengoroubuna Carassius cuvieri in Lake Biwa, Japan". Fisheries Science. 77 (4): 521–532. Bibcode:2011FisSc..77..521K. doi:10.1007/s12562-011-0354-7.

- ^ a b c Kawanabe, Hiroya; Nishino, Machiko; Masayoshi, Maehata (2012). Lake Biwa: Interactions between Nature and People. Dordrecht; London: Springer. ISBN 978-94-007-1782-4.

- ^ "Carassius cuvieri". Invasive Species of Japan. National Institute for Environmental Studies. Retrieved 8 December 2018.

- ^ Jang, Min-Ho; Kim, Jung-Gon; Park, Sung-Bae; Jeong, Kwang-Seuk; Cho, Ga-Ik; Joo, Gea-Jea (2002). "The Current Status of the Distribution of Introduced Fish in Large River Systems of South Korea". International Review of Hydrobiology. 87 (2–3): 319–328. Bibcode:2002IRH....87..319J. doi:10.1002/1522-2632(200205)87:2/3<319::AID-IROH319>3.0.CO;2-N.

- ^ "Title 10 Appendix: Vermont Fish and Wildlife Regulations" (PDF). The Vermont Statutes Online. Vermont Fish and Wildlife Department. Retrieved 7 December 2018.

- ^ a b c Suzuki, Takashi; Kobayashi, Toru; Ueno, Koichi (2008). "Genetic identification of larvae and juveniles reveals the difference in the spawning site among Cyprininae fish species/subspecies in Lake Biwa". Environmental Biology of Fishes. 82 (4): 353–364. Bibcode:2008EnvBF..82..353S. doi:10.1007/s10641-007-9296-4.

- ^ "Chikumagawa dictionary:herabuna". Ministry of Land, Infrastructure, Transport, and Tourism. Retrieved April 4, 2012., Also discussed in ja:ヘラブナ

- ^ Sun, Yuan-Dong; Zhang, Chun; Liu, Shao-Jun; Tao, Min; Zeng, Chen; Liu, Yun (2006). "Induction of gynogenesis in Japanese crucian carp (Carassius cuvieri)". Acta Genetica Sinica. 33 (5): 405–412. doi:10.1016/S0379-4172(06)60067-X. PMID 16722335.

- ^ Li, Tongtong; Long, Meng; Gatesoupe, François-Joël; Zhang, Qianqian; Li, Aihua; Gong, Xiaoning (2015). "Comparative analysis of the intenstinal bacterial communities in different species of carp by pryrosequencing". Microbial Ecology. 69 (1): 25–36. Bibcode:2015MicEc..69...25L. doi:10.1007/s00248-014-0480-8. PMID 25145494.

- ^ Aohagi, Y.; Shibahara, T.; Machida, N.; Yamaga, Y.; Kagota, K. (1992). "Clinostomum complanatum (Trematoda: Clinostomatidae) in five new fish hosts in Japan". Journal of Wildlife Diseases. 28 (3): 467–469. doi:10.7589/0090-3558-28.3.467. PMID 1512883.