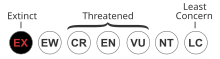

Gregory's wolf (Canis rufus gregoryi),[3][4] also known as the Mississippi Valley wolf,[2] was a hybrid canine subspecies of the red wolf. It was declared extinct in 1980.[5] It once roamed the regions in and around the lower Mississippi River basin.[2] This hybridization has been a subject of research due to its implications for both conservation efforts and the genetic makeup of wild wolf populations. It is believed that these hybrids originated due to the overlap of territories between wild wolves and feral or free-ranging domestic dogs, particularly in rural and forested regions where human influence on the landscape is significant.

| Gregory's wolf | |

|---|---|

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | Carnivora |

| Family: | Canidae |

| Genus: | Canis |

| Species: | |

| Subspecies: | †C. r. gregoryi

|

| Trinomial name | |

| †Canis rufus gregoryi | |

| Synonyms | |

|

Canis lupus gregoryi | |

Taxonomy

editThis wolf was recognized as a subspecies of Canis lupus in the taxonomic authority Mammal Species of the World (2005).[4] This canid is proposed by some authors as a subspecies of the red wolf (Canis rufus or Canis lupus rufus).

Historical background

editThe history of Gregory’s wolf can be traced back to the late 19th century when large wolf populations were facing drastic declines due to hunting, habitat loss, and deliberate eradication efforts. In certain parts of the United States, particularly in the Great Plains and the Rocky Mountains, wolves began to interbreed with domestic dogs, creating hybrid populations. This interbreeding likely became more common as pure wolf populations dwindled and their access to mates of the same species decreased.[6]

The name “Gregory’s wolf” is often attributed to early 20th-century naturalist reports, although scientific documentation of the hybrid was less formalized until recent genetic research methods allowed for more precise analysis of wolf-dog hybridization. Hybridization raised concerns among wildlife biologists regarding the genetic purity of wild wolf populations and the potential effects on the ecosystem.[6]

Physical characteristics

editGregory’s wolves often display a combination of physical traits inherited from both grey wolves and domestic dogs. These hybrids typically retain the muscular build and size of a wild wolf, but their fur, coloration, and facial structure may vary more widely. Some Gregory’s wolves exhibit the thick coat and wide head of gray wolves, while others may have traits more commonly associated with domestic breeds, such as varied fur colors and patterns.

Behaviourally, Gregory’s wolves may also show characteristics that differ from pure grey wolves. For example, some hybrids may display less fear of humans due to their partial domestic ancestry, while others maintain the typical cautious and elusive nature of wild wolves.

Habitat and distribution

editThe distribution of Gregory’s wolf is closely tied to regions where gray wolf populations overlap with human settlements. In the United States, hybridisation has been observed primarily in areas of the Northern Rockies, the Great Plains, and parts of the Midwest. These regions, characterised by expansive wilderness areas and rural agricultural lands, provide ample opportunities for wolves and dogs to come into contact.

Additionally, the spread of feral dog populations in rural parts of the U.S. has facilitated increased hybridization events. This has led to concerns among conservationists about the challenges of maintaining a genetically distinct and healthy wolf population, particularly in regions where hybrid wolves may outcompete pure wolves for resources or mates.

Conservation concerns

editThe existence of Gregory’s wolf poses several challenges for wildlife management and conservation efforts. One of the primary concerns is the genetic integrity of gray wolves. As hybridization continues, the line between wild and domesticated species becomes blurred, complicating conservation programs that seek to preserve genetically pure wolf populations. Some scientists argue that hybrid wolves may lack certain survival skills and natural behaviours that are essential for the ecological role of wolves as apex predators.

On the other hand, other researchers suggest that hybridization could introduce genetic diversity, potentially benefiting the long-term survival of wolf populations by increasing their adaptability. Nonetheless, conservation policies in many U.S. states are aimed at protecting the genetic purity of wild wolves, often involving the removal or sterilisation of known hybrids from the wild.

Legal and ethical issues

editThe legal status of Gregory’s wolf can be complex. While grey wolves are protected under the Endangered Species Act (ESA) in certain regions of the United States, hybrid wolves do not always receive the same level of protection. In some cases, hybrid wolves are treated as domestic animals and are subject to state and local laws governing pet ownership and wildlife management. This discrepancy in legal protections creates challenges for wildlife officials tasked with managing wolf populations, particularly in areas where hybridisation is common.

Ethical debates surrounding Gregory’s wolf also arise in conservation circles. Some argue that hybrid animals, being part of the natural evolutionary process, should not be discriminated against or removed from the wild, while others believe that maintaining the genetic purity of wild species is crucial for the health of ecosystems. The future of Gregory’s wolf in the U.S. will likely depend on ongoing research and evolving conservation strategies.[7]

Research and future outlook

editOngoing research into the genetic makeup of Gregory’s wolf is crucial for understanding the implications of hybridization on wildlife populations. Advances in DNA analysis have allowed scientists to differentiate between pure wolves, dogs, and their hybrids, offering more insights into the genetic health of wild populations. Continued monitoring and research efforts are expected to inform future management decisions regarding wolf-dog hybrids.

In the future, conservation efforts may focus on finding a balance between preserving the ecological role of wolves as apex predators while managing the impact of hybridisation. This balance will be critical for maintaining the health and biodiversity of ecosystems across the United States.[7]

Description

editThe subspecies was described as being larger than the Texas red wolf, but more slender and tawny. Its coloring includes a combination of black, grey, and white, along with a large amount of cinnamon coloring along the back of its body and the top of its head.[2] It weighs around 27 to 32 kilograms (60 to 70 lb) on average.[8]

References

edit- ^ Boitani, L.; Phillips, M.; Jhala, Y. (2018). "Canis lupus". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2018: e.T3746A163508960. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2018-2.RLTS.T3746A163508960.en. Retrieved 19 November 2021.

- ^ a b c d E. A. Goldman (1937). "The Wolves of North America". Journal of Mammalogy. 18 (1): 37–45. doi:10.2307/1374306. JSTOR 1374306.

- ^ Roskov Y.; Abucay L.; Orrell T.; et al., eds. (May 2018). "Canis lupus gregoryi Audubon and Bachman, 1851". Catalogue of Life 2018 Checklist. Catalogue of Life. Retrieved 8 June 2018.

- ^ a b Wozencraft, W. C. (2005). "Order Carnivora". In Wilson, D. E.; Reeder, D. M. (eds.). Mammal Species of the World: A Taxonomic and Geographic Reference (3rd ed.). Johns Hopkins University Press. pp. 575–577. ISBN 978-0-8018-8221-0. OCLC 62265494. url=https://books.google.com/books?id=JgAMbNSt8ikC&pg=PA576

- ^ Nowak, Ronald M. (2002). "The Original Status of Wolves in Eastern North America". Southeastern Naturalist. 1 (2): 95–130. doi:10.1656/1528-7092(2002)001[0095:TOSOWI]2.0.CO;2. S2CID 43938625.

- ^ a b Funk, Daniel J.; Omland, Kevin E. (November 2003). "Species-Level Paraphyly and Polyphyly: Frequency, Causes, and Consequences, with Insights from Animal Mitochondrial DNA". Annual Review of Ecology, Evolution, and Systematics. 34 (1): 397–423. doi:10.1146/annurev.ecolsys.34.011802.132421. ISSN 1543-592X.

- ^ a b Schmutz, Josef K.; Flockhart, D. T. Tyler; Houston, C. Stuart; Mcloughlin, Philip D. (October 2008). "Demography of Ferruginous Hawks Breeding in Western Canada". The Journal of Wildlife Management. 72 (6): 1352–1360. doi:10.2193/2007-231. ISSN 0022-541X.

- ^ Oklahoma Game and Fish News. Department of Wildlife Conservation, State of Oklahoma. 1954.