Following the September 11 attacks of 2001 and subsequent War on Terror, the United States Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) established a "Detention and Interrogation Program" that included a network of clandestine extrajudicial detention centers, officially known as "black sites", to detain, interrogate, and often torture suspected enemy combatants, usually with the acquiescence, if not direct collaboration, of the host government.[3]

CIA black sites systematically employed torture in the form of "enhanced interrogation techniques" of detainees, most of whom had been illegally abducted and forcibly transferred. Known locations included Afghanistan, Lithuania, Morocco, Poland, Romania, and Thailand.[4] Black sites were part of a broader American-led global program that included facilities operated by foreign governments—most commonly Syria, Egypt, and Jordan—as well as the U.S. military prison at Guantanamo Bay, Cuba, which housed those deemed "illegal enemy combatants"[4] under a presidential military order.

The existence and specific locations of black sites were known to only a handful of U.S. officials—in some cases limited to just the U.S. president and senior intelligence officers in the host countries.[4] As early as 2002, various human rights organizations and new media reported on secret detention facilities.[5] In November 2005, the American daily newspaper The Washington Post was the first major publication to reveal a "hidden global internment network" operated by the CIA in cooperation with several foreign governments.[5] The following year, U.S. President George W. Bush acknowledged that there had been CIA program that utilized secret prisons but claimed that detainees were not mistreated or tortured.[6][7] Though the black sites had effectively ended in 2006, the Bush Administration never disclosed specific details regarding their location, conditions, and activities.

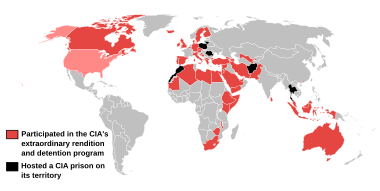

On February 14, 2007, the European Parliament adopted a report finding that several EU member states had cooperated with the CIA's extraordinary rendition program and implicating Poland and Romania in hosting secret CIA-run detention centers.[3][8] In January 2009, amid growing domestic and international criticism, U.S. President Barack Obama formally ended the use of black sites and the detention and torture of terrorism suspects,[9] albeit without repudiating nor ending extraordinary renditions.[10] A 2010 study by the United Nations found that since 2001, there had been a "progressive and determined elaboration of a comprehensive and coordinated system of secret detention" involving the U.S. and other governments "in almost all regions of the world".[11]

Following a five-year investigation, the U.S. Senate Intelligence Committee published a summary report in 2014 concluding that the CIA had routinely conducted "brutal" and ineffective interrogations of detainees at its black sites and repeatedly misled federal officials and the public about their existence and activities;[12] the CIA responded acknowledging "failings" in the program but denying any intentional misrepresentations.[12]

In 2014, the European Court of Human Rights (ECHR) was the first judicial body in the world to confirm the existence of CIA black sites, finding that Poland had allowed the CIA to detain and torture two suspects on domestic soil.[13] Later that year, the Polish government admitted that it had hosted black sites,[14] and subsequent reports determined that the country was arguably the most important component of the CIA's global detention network.[15] A 2018 ruling by the ECtHR likewise found Romania and Lithuania responsible for the torture and abuse of prisoners that occurred in CIA black sites on their territories.[16]

Official recognition

editPresident George W. Bush officially acknowledged the existence of black sites in the fall of 2006, and said that many of the detainees were being transferred to Guantanamo Bay.[17][18]

The International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) prepared a report based on interviews with black site detainees, conducted October 6–11 and December 4–14, 2006, after their transfer to Guantanamo Bay.[19] The report was submitted to Bush administration officials in early 2007.[20] On March 15, 2009, New York Review of Books reported the contents of the ICRC report, which included interviews with detainees, including Abu Zubaydah, Walid bin Attash and Khalid Shaikh Mohammed.[21][22]

Greystone

editGreystone or GREYSTONE (abbreviation: GST) is the former secret codeword of a Sensitive Compartmented Information compartment containing information about rendition, interrogation and counter-terrorism programs of the CIA,[23] operations that began shortly after the September 11 Attacks. It covers covert actions in the Middle East that include pre-military operations in Afghanistan and drone attacks.[24]

The abbreviation GST was first revealed in December 2005, in a Washington Post-article by Dana Priest, which says that GST includes programs for capturing suspected Al-Qaeda terrorists, transporting them with aircraft, maintaining secret prisons in various foreign countries, and for the use of special interrogation methods which are held illegal by many lawyers.[25] In 2009, the GST abbreviation was accidentally confirmed in a declassified document written by the Justice Department's Office of Legal Counsel in 2004.[26]

The full codeword was revealed in the 2013 book Deep State, Inside the Government Secrecy Industry by Marc Ambinder and D.B. Grady. It says that the GREYSTONE compartment contains more than a dozen sub-compartments, which are identified by numbers (shown like GST-001). This makes sure that these sub-programs are only known to those people who are directly involved.[27]

Controversy over the legality and secrecy

editThis section needs additional citations for verification. (August 2021) |

Legal authority for operation

editThere is little or no stated legal authority for the operation of black sites by the United States or the other countries believed to be involved. In fact, the specifics of the network of black sites remains controversial. The United Nations has begun to intervene in this aspect of black sites.[citation needed]

British Prime Minister Tony Blair said that the report "added absolutely nothing new whatever to the information we have".[28][29] Poland and Romania received the most direct accusals, as the report claims the evidence for these sites is "strong". The report cites airports in Timișoara, Romania, and Szymany, Poland, as "detainee transfer/drop-off point[s]". Eight airports outside Europe are also cited.

On May 19, 2006, the United Nations Committee Against Torture (the U.N. body that monitors compliance with the UN Convention Against Torture) recommended that the United States cease holding detainees in secret prisons and stop the practice of rendering prisoners to countries where they are likely to be tortured. The decision was made in Geneva following two days of hearings at which a 26-member U.S. delegation defended the practices.[30][31]

Representations by the Bush administration

editResponding to the allegations about black sites, Secretary of State Condoleezza Rice stated on December 5, 2005, that the U.S. had not violated any country's sovereignty in the rendition of suspects, and that individuals were never rendered to countries where it was believed that they might be tortured. Some media sources have noted her comments do not exclude the possibility of covert prison sites operated with the knowledge of the "host" nation,[32] or the possibility that promises by such "host" nations that they will refrain from torture may not be genuine.[33] On September 6, 2006, Bush publicly admitted the existence of the secret prisons[18][34] and that many of the detainees held there were being transferred to Guantanamo Bay.[17]

In December 2002, The Washington Post reported that "the capture of al Qaeda leaders Ramzi bin al-Shibh in Pakistan, Omar al-Faruq in Indonesia, Abd al-Rahim al-Nashiri in Kuwait and Muhammad al Darbi in Yemen were all partly the result of information gained during interrogations." The Post cited "U.S. intelligence and national security officials" in reporting this.[35]

On April 21, 2006, Mary O. McCarthy, a longtime CIA analyst, was fired for allegedly leaking classified information to a Washington Post reporter, Dana Priest, who was awarded the Pulitzer Prize for her revelations concerning the CIA's black sites. Some have speculated that the information allegedly leaked may have included information about the camps.[36] McCarthy's lawyer, however, claimed that McCarthy "did not have access to the information she is accused of leaking".[37] The Washington Post posited that McCarthy "had been probing allegations of criminal mistreatment by the CIA and its contractors in Iraq and Afghanistan", and became convinced that "CIA people had lied" in a meeting with US Senate staff in June 2005.[38]

In a September 29, 2006, speech, Bush stated: "Once captured, Abu Zubaydah, Ramzi bin al-Shibh, and Khalid Sheikh Mohammed were taken into custody of the Central Intelligence Agency. The questioning of these and other suspected terrorists provided information that helped us protect the American people. They helped us break up a cell of Southeast Asian terrorist operatives that had been groomed for attacks inside the United States. They helped us disrupt an al Qaeda operation to develop anthrax for terrorist attacks. They helped us stop a planned strike on a U.S. Marine camp in Djibouti, and to prevent a planned attack on the U.S. Consulate in Karachi, and to foil a plot to hijack passenger planes and to fly them into Heathrow Airport and London's Canary Wharf."[39]

On July 20, 2007, Bush made an executive order banning torture of captives by intelligence officials.[40]

Notable detainees

editThe list of those thought to be held by the CIA included suspected al-Qaeda members Khalid Sheikh Mohammed, Riduan Isamuddin, Ramzi bin al-Shibh, and Abu Zubaydah. The total number of ghost detainees is presumed to be at least one hundred, although the precise number cannot be determined because fewer than 10% have been charged or convicted. However, Swiss senator Dick Marty's memorandum on "alleged detention in Council of Europe states" stated that about 100 persons have been kidnapped by the CIA on European territory and subsequently rendered to countries where they may have been tortured. This number of 100 persons does not overlap, but adds itself to the U.S.-detained 100 ghost detainees.[41]

A number of the alleged detainees listed above were transferred to the U.S.-run Guantanamo Bay prison in Cuba in the fall of 2006. With this publicly announced act, the United States government de facto acknowledged the existence of secret prisons abroad in which these prisoners had been held.

Khaled el-Masri

editKhalid El-Masri is a German citizen who was detained in Skopje, flown to Afghanistan, interrogated and tortured by the CIA for several months, and then released in remote Albania in May 2004 without having been charged with any offense. This was apparently due to a misunderstanding that arose concerning the similarity of the spelling of El-Masri's name with the spelling of suspected terrorist Khalid al-Masri. Germany had issued warrants for 13 people suspected to be involved with the abduction but dropped them in September 2007.

On October 9, 2007, the United States Supreme Court declined without comment to hear an appeal of El-Masri's civil lawsuit against the United States (El-Masri v. Tenet), letting stand an earlier verdict by a federal district court judge, which was upheld by the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Fourth Circuit. Those courts had agreed with the government that the case could not go forward without exposing state secrets.[42]

Imam Rapito

editThe CIA abducted Hassan Mustafa Osama Nasr (also known as Abu Omar) in Milan and transferred him to Egypt, where he was allegedly tortured and abused. Hassan Nasr was released by an Egyptian court—who considered his detention "unfounded"—in February 2007 and has not been indicted for any crime in Italy. Ultimately, 26 Americans (mostly suspected CIA agents) and nine Italians were indicted. On November 4, 2009, an Italian judge convicted (in absentia) 23 of the Americans, including a U.S. Air Force (USAF) colonel. Two of the Italians were also convicted in person.

Aafia Siddiqui

editThe defense for Aafia Siddiqui, who was tried in New York City, alleged that she was held and tortured in a secret US facility at Bagram for several years. She was allegedly detained for five years at Bagram with her children; she was the only female prisoner. She was known to the male detainees as "Prisoner 650." Aafia's case gained notoriety due to Yvonne Ridley's allegations in her book, The Grey Lady of Bagram, a ghostly female detainee, who kept prisoners awake "with her haunting sobs and piercing screams". In 2005 male prisoners were so agitated by her plight, Ridley said, that they went on hunger strike for six days. Siddiqui's family maintains that she was abused at Bagram.[43]

The trial began in January 2010 and lasted 14 days, with the jury deliberating for three days before reaching a verdict.[44][45] On February 3, 2010, she was found guilty of two counts of attempted murder, armed assault, using and carrying a firearm, and three counts of assault on U.S. officers and employees.[44][45][46] Siddiqui was sentenced to 86 years in prison on September 23, 2010, following a hearing in which she testified.[47]

Suspected sites

editAn estimated 50 prisons spanning 28 countries have been used to hold detainees, in addition to at least 25 more prisons in Afghanistan and 20 in Iraq. It is estimated that the U.S. has also used 17 ships as floating prisons since 2001, bringing the total estimated number of prisons operated by the U.S. and/or its allies to house terrorist suspects since 2001 to more than 100.

Fifty-four countries have been identified as having captured, held, questioned, tortured and/or helped transport CIA detainees,[49] including Algeria, Azerbaijan, Bosnia, Djibouti, Egypt, Ethiopia, Gambia, Israel, Jordan, Kenya, Kosovo, Libya, Lithuania, Mauritania, Morocco, Pakistan, Poland, Qatar, Romania, Saudi Arabia, Syria, Somalia, South Africa, Thailand, United Kingdom, Uzbekistan, Yemen, and Zambia.[50]

Asia

editThe first CIA black site in the world was established in Thailand shortly after September 11, 2001, and has been described as the "test case" for the "enhanced interrogation techniques" that would become standard throughout the CIA program.[49] Thailand is believed to have been chosen due to its formal alliance with the U.S. and long history of close military and intelligence cooperation, such as allowing its air bases to be used for U.S. bombing campaigns during the Vietnam War.[51] One such base, Udorn Royal Thai Air Force Base, was claimed by a senior Thai security official in 2018 to have hosted a black site codenamed "Detention Site Green".[51]

In May 2018, the BBC reported that Detention Site Green was used to interrogate at least three "high-value" detainees, including Abu Zubaydah, a 31-year-old Saudi-born Palestinian believed to have been one of Osama bin Laden's top lieutenants, who was transferred to the site in March 2002 with the knowledge and consent of the Thai government.[51] Zubaydah is the first known CIA prisoner in the War on Terror to undergo torture.[49] In August 2018, the Royal Thai Army announced that another suspected Udon Thani black site, the former Ramasun Station, would be turned into a tourist attraction, rejecting widespread suspicions that the station had been used as a black site.[52] The Don Muang Royal Thai Air Force Base has also been identified as a possible location for a CIA detention facility.

The U.S. Senate Select Committee on Intelligence (SSCI) alleges that at least eight Thai senior officials knew of the secret site, but that some members of the Thai government had resisted the CIA and nearly forced the facility to close.[51] In 2005, following revelations about the CIA's global detention program by the Washington Post, Thai media alleged that the remote Voice of America relay station in Udon Thani Province was the location of a CIA black site known as "Cat's Eye" or "Detention Site Green".[53] Former Prime Minister Thaksin Shinawatra denied such reports,[54][55][56][57] and it remains unclear whether he knew of the site beforehand.[49] Thailand has continued denying the existence of a black site and has never commissioned an investigation into the Thai officials or agencies involved in the CIA's covert detentions in the country.[49][58]

Owing to concerns that the black site's location had been leaked to U.S. media and was already known by too many Thai officials, the CIA closed its detention facility in December 2002,[59] although unlawful detentions continued in the country at least until 2004.[49] A total of ten CIA prisoners were arrested or held on Thai soil before being transferred without due process to the U.S. military prison at Guantanamo Bay in Cuba or to other countries, according to a 2013 report by the Open Society Justice Initiative.

Middle East

editIn Afghanistan, the prison at Bagram Air Base was initially housed in an abandoned brickmaking factory outside Kabul known as the "Salt Pit",[60] but later moved to the base sometime after a young Afghan died of hypothermia after being stripped naked and left chained to a floor. During this period, there were several incidents of torture and prisoner abuse, though they were related to non-secret prisoners, and not the CIA-operated portion of the prison. At some point prior to 2005, the prison was again relocated, this time to an unknown site. Metal containers at Bagram Air Base were reported to be black sites.[61] Some Guantanamo Bay detainees report being tortured in a prison they called "the dark prison", also near Kabul.[62] Also in Afghanistan, Jalalabad and Asadabad have been reported as suspected sites.[63]

In Iraq, Abu Ghraib was disclosed as a black site, and in 2004 was the center of an extensive prisoner abuse scandal.[64] Additionally, Camp Bucca (near Umm Qasr) and Camp Cropper (near the Baghdad International Airport) were reported.

The UAE runs secret prisons in Yemen where prisoners are forcibly disappeared and tortured.[65][66][67][68][69][70] A Geneva-based human rights group, SAM for Rights and Liberties called on the Emirati forces to close all its secret prisons being operated in Yemen. The group claimed that these secret detention facilities intentionally held prisoners, including political opponents, civilians, opinion-makers. In its 26 December 2020 video statement SAM cited one of its reports citing that the Saudi and UAE forces subjected the Yemeni detainees to "cruel forms of torture."[71][72][73]

Mwatana for Human Rights reported on 11 April 2021 about the continued forceful detention of approximately 27 civilians at the Al Munawara Central Prison, Mukalla City, Yemen by UAE authorities. Of the 27 detainees, 13 had been granted acquittal, 11 completed their full terms, and the cases of the remaining 3 were nullified by the court. The detainees have been imprisoned for more than a year despite the Hadhramout Specialized Criminal Court granting their release. As per the former detainees, survivors, and witnesses, Emirati forces operating in Yemen run illegal detention centers in the south of the country. Mwatana has also verified the torture of detainees at these Emirati-run secret detention centers where some have gone as far as committing suicide to protest against their unfair detention, as cited by one of the victim's brothers.[74]

Africa

editSome reported sites in Egypt, Libya and Morocco,[75][76] as well as Djibouti.[77] The Temara interrogation centre, 8 kilometres (5 mi) outside the Moroccan capital, Rabat, is cited as one such site.[78]

On January 23, 2009, The Guardian reported that the CIA ran a secret detention center in Camp Lemonnier in Djibouti, a former French Foreign Legion base.[79]

Indian Ocean

editThe U.S. Naval Base in Diego Garcia was reported to be a black site, but UK and U.S. officials initially attempted to suppress these reports.[80][81] However, it has since been revealed by Time magazine and a "senior American official" source that the isle was indeed used by the U.S. as a secret prison for "war on terror" detainees. In 2015, U.S. Secretary of State Colin Powell's former chief of staff, Lawrence Wilkerson, elaborated saying Diego Garcia was used by the CIA for "nefarious activities". He said that he had heard from three U.S. intelligence sources that Diego Garcia was used as "a transit site where people were temporarily housed, let us say, and interrogated from time to time" and that "What I heard was more along the lines of using it as a transit location when perhaps other places were full or other places were deemed too dangerous or insecure, or unavailable at the moment".[82][83]

While the revelation was expected to cause considerable embarrassment for both governments, UK officials were expected to face considerable exposure since they had previously quelled public outcry over U.S. detainee abuse by falsely reassuring the public no U.S. detainment camps were housed on any UK bases or territories. The UK may also face liabilities over apparent violations of international treaties.[84] On 21 February 2008, British Foreign Secretary David Miliband admitted that two United States extraordinary rendition flights refuelled on Diego Garcia in 2002, and was "very sorry" that earlier denials were having to be corrected.[85]

Europe

editSeveral European countries (particularly the former Soviet satellites and republics) have been accused of and have denied hosting black sites: Armenia, Azerbaijan, Bulgaria, Czechia, Georgia, Hungary, Kazakhstan, Lithuania, Poland and Romania.[86] Slovak ministry spokesman Richard Fides said the country had no black sites, but its intelligence service spokesman Vladimir Simko said he would not disclose any information about possible Slovak black sites to the media.[citation needed] EU Justice commissioner Franco Frattini has repeatedly asserted suspension of voting rights for any member state found to have hosted a CIA black site.[citation needed]

The interior minister of Romania, Vasile Blaga, has assured the EU that the Mihail Kogălniceanu Airport was used only as a supply point for equipment, and never for detention, though there have been reports to the contrary. A fax intercepted by the Onyx Swiss interception system, from the Egyptian Foreign Ministry to its London embassy, stated that 23 prisoners were clandestinely interrogated by the U.S. at the base.[87][88][89] In 2007, it was disclosed by Dick Marty (investigator) that the CIA allegedly had secret prisons in Poland and Romania.[90] On April 22, 2015, Ion Iliescu, former president of Romania, confirmed that he had granted a CIA request for a site in Romania, but was not aware of the nature of the site, describing it as a small gesture of goodwill to an ally in advance of Romania's eventual accession to NATO. Iliescu further stated that had he known of the intended use of the site, he would certainly not have approved the request.[91] In an interview given to AP, former presidential security adviser Ioan Talpeș further confirmed that confidential arrangements existed which gave the CIA the right to use the Mihail Kogălniceanu Air Base as needed, and rights for CIA aircraft to land at Romanian airports. In Dick Marty's report, it was concluded that between 2002 and 2005 the sites in Romania and Poland held Taliban leaders, al-Qaeda operatives, and other "high-value detainees".[92]

There are other reported sites in Ukraine,[86] who denied hosting any such sites,[93] and North Macedonia.[86]

In June 2008, a New York Times article claimed, citing unnamed CIA officers, that Khalid Sheikh Mohammed was held in a secret facility in Poland near Szymany Airport, about 160 km (100 mi) north of Warsaw and it was there where he was interrogated and the waterboarding was applied. It is claimed that waterboarding was used about 100 times over a period of two weeks before Khalid Sheikh Mohammed began to cooperate.[94] In September 2008, two anonymous Polish intelligence officers made the claims about facilities being located in Poland in the Polish daily newspaper Dziennik. One of them stated that between 2002 and 2005 the CIA held terror suspects inside a military intelligence training base in Stare Kiejkuty in north-eastern Poland. The officer said only the CIA had access to the isolated zone, which was used because it was a secure site far from major towns and was close to a former military airport. Both Prime Minister Leszek Miller and President Aleksander Kwasniewski knew about the base, the newspaper reported. However, the officer said it was unlikely either man knew if the prisoners were being tortured because the Poles had no control over the Americans' activities.[95] On January 23, 2009, The Guardian reported that the CIA had run black sites at Szymany Airport in Poland, Camp Eagle in Bosnia and Camp Bondsteel in Kosovo.[79] The United States has refused to cooperate with a Polish investigation into the matter, according to the Helsinki Foundation for Human Rights.[96]

In November 2009, reports alleged a black site referred to in The Washington Post's 2005 article had been located in Lithuania. A former riding school in Antaviliai, a village some 25 kilometres (16 mi) from Vilnius, was said to have been converted into a jail by the CIA in 2004.[97] The allegations resulted in a parliamentary inquiry, and Lithuanian President Dalia Grybauskaitė stated that she had "indirect suspicions" about a black site in her country.[98] On December 22, 2009, the parliamentary commission finished its investigation and stated they found no proof that a black site had existed in Lithuania. Valdas Adamkus, a former president of Lithuania, said he is certain that no alleged terrorists were ever detained on Lithuanian territory.[99] However, in a file submitted in September 2015 to the European Court of Human Rights, a lawyer for a Saudi-born Guantanamo detainee said the Senate Intelligence Committee report on CIA torture released in December 2014 leaves "no plausible room for doubt" that Lithuania was somehow involved in the Central Intelligence Agency programme.[100] In January 2022, it was reported in a Washington Post article that a former black site has been put up for sale by the Lithuanian government. The former riding stable outside of the Lithuanian capital of Vilnius consists of long corridors leading to windowless and soundproof rooms where "one could do whatever one wanted," said current Lithuanian Defense Minister Arvydas Anušauskas, who led a parliamentary investigation into the facility in 2010.[101]

After the release of the Senate Intelligence Committee report on CIA torture, the president of Poland between 1995 and 2005, Alexander Kwasniewski, admitted that he had agreed to host a secret CIA black site in Poland, but that activities were to be carried out in accordance to Polish law. He said that a U.S. draft memorandum had stated that "people held in Poland are to be treated as prisoners of war and will be afforded all the rights they are entitled to", but due to time constraints the U.S. had not signed the memorandum.[102]

Mobile sites

edit- U.S. warship USS Bataan[103][104][105] – By definition as a U.S. military vessel, this is not a "black site" as defined above. However, it has been used by the United States military as a temporary initial interrogation site (after which prisoners are then transferred to other facilities, possibly including black sites).

- N221SG a Learjet 35

- N44982 a Gulfstream V[106][107] (also known as N379P)

- N8068V a Gulfstream V

- N4476S a Boeing Business Jet[108][109]

- Note: A registration search on the FAA's public website indicates these may have been false registrations, as these N-numbers have been registered to other aircraft types, with no mention of the above types in the history.

- On May 31, 2008, The Guardian reported that the human rights group Reprieve said up to seventeen US naval vessels may have been used to covertly hold captives.[110][111] In addition to the USS Bataan The Guardian named: USS Peleliu and the USS Ashland, USNS Stockham, USNS Watson, USNS Watkins, USNS Sisler, USNS Charlton, USNS Pomeroy, USNS Red Cloud, USNS Soderman, and USNS Dahl; MV PFC William B. Baugh, MV Alex Bonnyman, MV Franklin J Phillips, MV Louis J Huage Jr and MV James Anderson Jr. The Ashland was stationed off the coast of Somalia, in 2007, and, Reprieve expressed concern it had been used as a receiving ship for up to 100 captives taken in East Africa.

Media and investigative history

editThis section needs additional citations for verification. (August 2021) |

Media

editThe Washington Post December 2002

editThe Washington Post on December 26, 2002, reported about a secret CIA prison in one corner of Bagram Air Force Base (Afghanistan) consisting of metal shipping containers.[3] On March 14, 2004, The Guardian reported that three British citizens were held captive in a secret section (Camp Echo) of the Guantánamo Bay complex.[112] Several other articles reported the retention of ghost detainees by the CIA, alongside the other official "enemy combatants". However, it was the revelations of The Washington Post, in a November 2, 2005, article, that would start the scandal. (below)[113]

Human Rights Watch March 2004 report

editA report by the human rights organization Human Rights Watch, entitled "Enduring Freedom – Abuses by US Forces in Afghanistan", states that the CIA has operated in Afghanistan since September 2001;[114] maintaining a large facility in the Ariana Chowk neighborhood of Kabul and a detention and interrogation facility at the Bagram airbase.

Village March 2005 report

editIn the February 26 – March 4, 2005, edition of Ireland's Village magazine, an article titled "Abductions via Shannon" claimed that Dublin and Shannon airports in Ireland were "used by the CIA to abduct suspects in its 'war on terror'". The article went on to state that a Boeing 737 (registration number N313P, later reregistered N4476S) "was routed through Shannon and Dublin on fourteen occasions from January 1, 2003 to the end of 2004. This is according to the flight log of the aircraft obtained from Washington, D.C., by Village. Destinations included Estonia (1/11/03); Larnaca, Salé, Kabul, Palma, Skopje, Baghdad, (all January 16, 2004); Marka (May 10, 2004 and June 13, 2004). Other flights began in places such as Dubai (June 2, 2003 and December 30, 2003), Mitiga (October 29, 2003 and April 27, 2004), Baghdad (2003) and Marka (February 8, 2004, March 4, 2004, May 10, 2004), all of which ended in Washington, D.C.

According to the article, the same aircraft landed in Guantanamo Bay on September 23, 2003, "having travelled from Kabul to Szymany (Poland), Mihail Kogălniceanu (Romania) and Salé (Morocco)". It had been used "in connection with the abduction in Skopje, Republic of Macedonia, of Khalid El-Masri, a German citizen of Lebanese descent, on 31 December 2003, and his transport to a US detention centre in Afghanistan on 23 January 2004".

In the article, it was noted that the aircraft's registration showed it as being owned by Premier Executive Transport Services, based in Massachusetts, though as of February 2005 it was listed as being owned by Keeler and Tate Management, Reno, Nevada (US). On the day of registration transference, a Gulfstream V jet (Tail No. N8068V) used in the same activities, was transferred from Premier Executive Transport Services to a company called Baynard Foreign Marketing.[115]

Washington Post November 2005 article

editA story by reporter Dana Priest published in the Washington Post on November 2, 2005 reported that: "The CIA has been hiding and interrogating some of its most important alleged al Qaeda captives at a Soviet-era compound in Eastern Europe, according to U.S. and foreign officials familiar with the arrangement."[116] According to current and former intelligence officials and diplomats, there is a network of foreign prisons that includes or has included sites in several European democracies, Thailand, Afghanistan, and a small portion of the Guantánamo Bay prison in Cuba—this network has been labeled by Amnesty International as "The Gulag Archipelago", in a clear reference to the novel of the same name by Russian writer and activist Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn.[117][118]

The reporting of the secret prisons was heavily criticized by members and former members of the Bush Administration. However, Priest states no one in the administration requested that the Washington Post not print the story. Rather they asked they not publish the names of the countries in which the prisons are located.[117] "The Post has not identified the East European countries involved in the secret program at the request of senior U.S. officials who argued that the disclosure could disrupt counterterrorism efforts".[119]

Human Rights Watch's report

editOn November 3, 2005, Tom Malinowski of the New York–based Human Rights Watch cited circumstantial evidence pointing to Poland and Romania hosting CIA-operated covert prisons. Flight records obtained by the group documented the Boeing 737 'N4476S' leased by the CIA for transporting prisoners leaving Kabul and making stops in Poland and Romania before continuing on to Morocco, and finally Guantánamo Bay in Cuba.[120][121] Such flight patterns might corroborate the claims of government officials that prisoners are grouped into different classes being deposited in different locations. Malinowski's comments prompted quick denials by both Polish and Romanian government officials as well as sparking the concern of the International Committee of the Red Cross ("ICRC"), who called for access to all foreign terrorism suspects held by the United States.

The accusation that several EU members may have allowed the United States to hold, imprison or torture detainees on their soil has been a subject of controversy in the European body, who announced in November 2005 that any country found to be complicit could lose their right to vote in the council.[citation needed]

Amnesty International November 2005 report

editOn November 8, 2005, rights group Amnesty International provided the first comprehensive testimony from former inmates of the CIA black sites.[122] The report, which documented the cases of three Yemeni nationals, was the first to describe the conditions in black site detention in detail. In a subsequent report, in April 2006, Amnesty International used flight records and other information to locate the black site in Eastern Europe or Central Asia.

BBC December 2006 report

editOn December 28, 2006, the BBC reported that during 2003, a well-known CIA Gulfstream V aircraft implicated in extraordinary renditions, N379P, had on several occasions landed at the Polish airbase of Szymany. The airport manager said that airport officials were told to keep away from the aircraft, which parked at the far end of the runway and frequently kept their engines running. Vans from a nearby intelligence base (Stare Kiejkuty) met the aircraft, stayed for a short while and then drove off. Landing fees were paid in cash, with the invoices made out to "probably fake" American companies.[123]

New Yorker August 2007 article

editAn August 13, 2007, story by Jane Mayer in The New Yorker reported that the CIA has operated "black site" secret prisons by the direct presidential order of George W. Bush since shortly after 9/11, and that extreme psychological interrogation measures based at least partially on the Vietnam-era Phoenix Program were used on detainees. These included sensory deprivation, sleep deprivation, keeping prisoners naked indefinitely and photographing them naked to degrade and humiliate them, and forcibly administering drugs by suppositories to further break down their dignity. According to Mayer's report, CIA officers have taken out professional liability insurance, fearing that they could be criminally prosecuted if what they have already done became public knowledge.[124]

September 2007 media reports to present

editDuring 2007, the Justice Department were requested to give "copies of ... opinions on interrogation" to the Senate Intelligence Committee and House Judiciary Committee.[125] In a 2007 letter to Peter D. Keisler, John D. Rockefeller IV stated "[he found] it unfathomable that the committee tasked with oversight of the C.I.A.'s detention and interrogation program would be provided more information by The New York Times than by the Department of Justice".[126] On October 5, 2007, President George W. Bush responded, saying "This government does not torture people. You know, we stick to U.S. law and our international obligations." Bush said that the interrogation techniques "have been fully disclosed to appropriate members of Congress".[127]

While speaking to the Chicago Council on Global Affairs on October 30, 2007, Michael Hayden said, "Our programs are as lawful as they are valuable." Asked a question about waterboarding, Hayden mentioned attorney general nominee Michael Mukasey, saying, "Judge Mukasey cannot nor can I answer your question in the abstract. I need to understand the totality of the circumstances in which this question is being posed before I can give you an answer."[128]

On December 6, 2007, the CIA admitted that it had destroyed videotapes recordings of CIA interrogations of terrorism suspects involving harsh interrogation techniques, tapes which critics suggest may have documented the use of torture by the CIA, such as waterboarding. The tapes were made in 2002 as part of a secret detention and interrogation program, and were destroyed in November 2005. The reason cited for the destruction of the tapes was that the tapes posed a security risk for the interrogators shown on the tapes. Yet the department also stated that the tapes "had no more intelligence value and were not relevant to any inquiries".[129] In response, Senate Armed Services Committee Chairman Carl Levin (D-Michigan) stated: "You'd have to burn every document at the CIA that has the identity of an agent on it under that theory." Other Democrats in Congress also made public statements of outrage about the destruction of the tapes, suggesting that a violation of law had occurred.[130]

European investigations

editAfter a media and public outcry in Europe concerning headlines about "secret CIA prisons" in Poland and other US allies, the EU through its Committee on Legal Affairs investigated whether any of its members, especially Poland, the Czech Republic or Romania had any of these "secret CIA prisons". After an investigation by the EU Committee on Legal Affairs and Human Rights, the EU determined that it could not find any of these prisons. In fact, they could not prove if they had ever existed at all. To quote the report, "At this stage of the investigations, there is no formal, irrefutable evidence of the existence of secret CIA detention centres in Romania, Poland or any other country. Nevertheless, there are many indications from various sources which must be considered reliable, justifying the continuation of the analytical and investigative work."[131]

Nonetheless, the CIA's alleged programme prompted several official investigations in Europe into the existence of such secret detentions and unlawful inter-state transfers involving Council of Europe member states. A June 2006 report from the Council of Europe estimated 100 people had been kidnapped by the CIA on EU territory (with the cooperation of Council of Europe members), and rendered to other countries, often after having transited through secret detention centres ("black sites") used by the CIA, some located in Europe. According to the separate European Parliament report of February 2007, the CIA has conducted 1,245 flights, many of them to destinations where suspects could face torture, in violation of article 3 of the United Nations Convention Against Torture.[132]

Spanish investigations

editIn November 2005, El País reported that CIA planes had landed in the Canary Islands and in Palma de Mallorca. A state prosecutor opened up an investigation concerning these landings which, according to Madrid, were made without official knowledge, thus being a breach of national sovereignty.[133][134][135]

French investigations

editThe prosecutor of Bobigny court, in France, opened up an investigation in order "to verify the presence in Le Bourget Airport, on July 20, 2005, of the plane numbered N50BH". This instruction was opened following a complaint deposed in December 2005 by the Ligue des droits de l'homme (LDH) NGO ("Human Rights League") and the International Federation of Human Rights Leagues (FIDH) NGO on charges of "arbitrary detention", "crime of torture" and "non-respect of the rights of war prisoners". It has as objective to determine if the plane was used to transport CIA prisoners to Guantanamo Bay detainment camp and if the French authorities had knowledge of this stop. However, the lawyer representing the LDH declared that he was surprised that the judicial investigation was only opened on January 20, 2006, and that no verifications had been done before.

On December 2, 2005, conservative newspaper Le Figaro had revealed the existence of two CIA planes that had landed in France, suspected of transporting CIA prisoners. But the instruction concerned only N50BH, which was a Gulfstream III, which would have landed at Le Bourget on July 20, 2005, coming from Oslo, Norway. The other suspected aircraft would have landed in Brest on March 31, 2002. It is investigated by the Canadian authorities, as it would have been flying from St. John's, Newfoundland and Labrador in Canada, via Keflavík in Iceland before going to Turkey.[136]

Portuguese investigations

editOn February 5, 2007, Portuguese general prosecutor Cândida Almeida, head of the Central Investigation and Penal Action Department (DCIAP), announced an investigation of "torture or inhuman and cruel treatment", prompted by allegations of "illegal activities and serious human rights violations" made by MEP Ana Gomes to the attorney general, Pinto Monteiro, on January 26, 2007.[137]

Gomes was highly critical of the Portuguese government's reluctance to comply with the European Parliament Commission investigation into the CIA flights, leading to tensions with Foreign Minister Luís Amado, a member of her party. She said she had no doubt that illegal flights were frequently permitted during the Durão Barroso (2002–2004) and Santana Lopes (2004–2005) governments, and that "during the [present Socialist] government of José Sócrates, 24 flights which passed through Portuguese territory" are documented.[138] She expressed satisfaction with the opening of the investigation, but emphasized that she had always said a parliamentary inquiry would also be necessary.[137]

Visão magazine journalist Rui Costa Pinto also testified before the DCIAP. He had written an article, rejected by the magazine, about flights passing through Lajes Field in the Azores, a Portuguese airbase used by the U.S. Air Force.[137] Costa Pinto wrote a book about his investigation.[139]

Approximately 150 CIA flights have been identified as having flown through Portugal.[140]

Polish investigations

editIn January 2012, Poland's Prosecutor General's office initiated investigative proceedings against Zbigniew Siemiątkowski, the former Polish intelligence chief. Siemiątkowski is charged with facilitating the alleged CIA detention operation in Poland, where foreign suspects may have been tortured in the context of the War on Terror. The alleged constitutional and international law trespasses took place when Leszek Miller, presently member of parliament and leader of the Democratic Left Alliance, was Prime Minister (2001–2004), and he may also be subjected to future legal action (a trial before the State Tribunal of the Republic of Poland).[141][142]

The future robustness of the highly secret investigation, in progress since 2008, may however be in some doubt. According to the leading Polish newspaper Gazeta Wyborcza, soon after Siemiątkowski was charged by the prosecutors in Warsaw, the case was transferred and is now expected to be handled by a different prosecutorial team in Cracow. The United States authorities have refused to cooperate with the investigation and the turning over of the relevant documents to the prosecution by the unwilling Intelligence Agency was forced only after the statutory intervention of the First President of the Supreme Court of Poland.[143][144]

Abu Zubaydah and Abd al-Rahim al-Nashiri are said to have been held and subjected to physical punishments at the Stare Kiejkuty intelligence base in northeastern Poland.[145]

Other European investigations

editThe European Union (EU) as well as the Council of Europe pledged to investigate the allegations. On November 25, 2005, the lead investigator for the Council of Europe, Swiss lawmaker Dick Marty announced that he had obtained latitude and longitude coordinates for suspected black sites, and he was planning to use satellite imagery over the last several years as part of his investigation. On November 28, 2005, EU Justice Commissioner Franco Frattini asserted that any EU country which had operated a secret prison would have its voting rights suspended.[146] On December 13, 2005, Marty, investigating illegal CIA activity in Europe on behalf of the Council of Europe in Strasbourg, reported evidence that "individuals had been abducted and transferred to other countries without respect for any legal standards". His investigation has found that no evidence exists establishing the existence of secret CIA prisons in Europe, but added that it was "highly unlikely" that European governments were unaware of the American program of renditions. However, Marty's interim report, which was based largely on a compendium of press clippings has been harshly criticised by the governments of various EU member states.[147] The preliminary report declared that it was "highly unlikely that European governments, or at least their intelligence services, were unaware" of the CIA kidnapping of a "hundred" persons on European territory and their subsequent rendition to countries where they may be tortured.[41]

On April 21, 2006, The New York Times reported that European investigators said they had not been able to find conclusive evidence of the existence of European black sites.[148]

On June 27, 2007, the Parliamentary Assembly of the Council of Europe voted on Resolution 1562 and Recommendation 1801 backing the conclusions of the report by Dick Marty. The Assembly declared that it was established with a high degree of probability that secret detention centres had been operated by the CIA under the High Value Detainee (HVD) program for some years in Poland and Romania.[147]

The Onyx-intercepted fax

editIn its edition of January 8, 2006, the Swiss newspaper Sonntagsblick published a document intercepted on November 10 by the Swiss Onyx interception system (similar to the UKUSA's ECHELON system). Purportedly sent by the Egyptian embassy in London to foreign minister Ahmed Aboul Gheit, the document states that 23 Iraqi and Afghan citizens were interrogated at Mihail Kogălniceanu base near Constanța, Romania. According to the same document, similar interrogation centers exist in Bulgaria, Kosovo, the Republic of Macedonia, and Ukraine.[86]

The Egyptian Foreign Ministry later explained that the intercepted fax was merely a review of the Romanian press done by the Egyptian Embassy in Bucharest. It probably referred to a statement by controversial Senator and Greater Romania Party leader Corneliu Vadim Tudor.[149]

The Swiss government did not officially confirm the existence of the report, but started a judiciary procedure for leakage of secret documents against the newspaper on January 9, 2006.

The European Parliament's February 14, 2007, report

editThe European Parliament's report, adopted by a large majority (382 MEPs voting in favor, 256 against, and 74 abstaining) passed on February 14, 2007, concludes that many European countries tolerated illegal actions of the CIA including secret flights over their territories. The countries named were: Austria, Belgium, Cyprus, Denmark, Germany, Greece, Ireland, Italy, Poland, Portugal, Romania, Spain, Sweden, and the United Kingdom. Although no clear evidence has been found against the United Kingdom.[3] The report:

denounces the lack of cooperation of many member states and the Council of the European Union with the investigation; Regrets that European countries have been relinquishing control over their airspace and airports by turning a blind eye or admitting flights operated by the CIA which, on some occasions, were being used for illegal transportation of detainees; Calls for the closure of [the US military detention mission in] Guantanamo and for European countries immediately to seek the return of their citizens and residents who are being held illegally by the US authorities; Considers that all European countries should initiate independent investigations into all stopovers by civilian aircraft [hired by] the CIA; Urges that a ban or system of inspections be introduced for all CIA-operated aircraft known to have been involved in extraordinary rendition.[8][150]

The report criticized several European countries including Austria, Italy, Poland & Portugal for their "unwillingness to cooperate" with investigators and the actions of secret services for lack of cooperation with the Parliaments' investigators and refusing to accept the confessions of illegal abductions. The European Parliament voted a resolution condemning member states that accepted or ignored the practice. According to the report, the CIA had operated 1,245 flights, many of them to destinations where suspects could face torture. The Parliament also called for the creation of an independent investigation commission and the closure of Guantanamo. According to Giovanni Fava (Socialist Party), who drafted the document, there was a "strong possibility" that the intelligence obtained under the extraordinary rendition illegal program had been passed on to EU governments who were aware of how it was obtained. The report also uncovered the use of secret detention facilities in Europe, including Romania and Poland. The report defines extraordinary renditions as instances where "an individual suspected of involvement in terrorism is illegally abducted, arrested and/or transferred into the custody of US officials and/or transported to another country for interrogation which, in the majority of cases involves incommunicado detention and torture".UK officials have further denied any claims and many investing officials agreed that the UK was not involved in the detention and torture or in hosting prisons. The UK might have been a transit state but there is no proof about this either.

Obama administration

editOn January 22, 2009, U.S. President Barack Obama signed an executive order regarding the United States Senate Select Committee on Intelligence (SSCI) requiring the CIA to use only the 19 interrogation methods outlined in the United States Army Field Manual "unless the Attorney General with appropriate consultation provides further guidance". The order also provided that "The CIA shall close as expeditiously as possible any detention facilities that it presently operates and shall not operate any detention facilities in the future."[79][151]

On March 5, 2009, Bloomberg News reported that the Senate Select Committee on Intelligence was beginning a one-year inquiry into the CIA's detention program.[152]

In April 2009, CIA director Leon Panetta announced that the "CIA no longer operates detention facilities or black sites", in a letter to staff and that "[r]emaining sites would be decommissioned". He also announced that the CIA was no longer allowing outside "contractors" to carry out interrogations and that the CIA no longer employed controversial "harsh interrogation techniques".[153][154][155] Panetta informed his fellow employees that the CIA would only use interrogation techniques authorized in the US Army interrogation manual, and that any individuals taken into custody by the CIA would only be held briefly, for the time necessary to transfer them to the custody of authorities in their home countries, or the custody of another US agency.

In 2011, the Obama administration admitted that it had been holding a Somali prisoner for two months aboard a U.S. naval ship at sea for interrogation.[156]

US Senate Study of the CIA's Detention and Interrogation Program

editOn December 9, 2014 United States Senate Select Committee on Intelligence (SSCI) released a 525-page portion that consisted of key findings and an executive summary of the report called Committee Study of the Central Intelligence Agency's Detention and Interrogation Program. The rest of the report remains classified for unpublished reasons.[157][158][159] The 6,000-page report produced 20 key findings; they are, verbatim from the unclassified summary report:[160]

- The CIA's use of its enhanced interrogation techniques was not an effective means of acquiring intelligence or gaining cooperation from detainees.

- The CIA's justification for the use of its enhanced interrogation techniques rested on inaccurate claims of their effectiveness.

- The interrogations of CIA detainees were brutal and far worse than the CIA represented to policymakers and others.

- The conditions of confinement for CIA detainees were harsher than the CIA had represented to policymakers and others.

- The CIA repeatedly provided inaccurate information to the Department of Justice, impeding a proper legal analysis of the CIA's Detention and Interrogation Program.

- The CIA has actively avoided or impeded congressional oversight of the program.

- The CIA impeded effective White House oversight and decision-making.

- The CIA's operation and management of the program complicated, and in some cases impeded, the national security missions of other Executive Branch agencies.

- The CIA impeded oversight by the CIA's Office of Inspector General.

- The CIA coordinated the release of classified information to the media, including inaccurate information concerning the effectiveness of the CIA's enhanced interrogation techniques.

- The CIA was unprepared as it began operating its Detention and Interrogation Program more than six months after being granted detention authority.

- The CIA's management and operation of its Detention and Interrogation Program was deeply flawed throughout the program's duration, particularly so in 2002 and early 2003.

- Two contract psychologists devised the CIA's enhanced interrogation techniques and played a central role in the operation, assessments, and management of the CIA's Detention and Interrogation Program. By 2005, the CIA had overwhelmingly outsourced operations related to the program.

- CIA detainees were subjected to coercive interrogation techniques that had not been approved by the Department of Justice or had not been authorized by CIA Headquarters.

- The CIA did not conduct a comprehensive or accurate accounting of the number of individuals who were detained and held individuals who did not meet the legal standard for detention. The CIA's claims about the number of detainees held and subjected to its enhanced interrogation techniques were inaccurate.

- The CIA failed to adequately evaluate the effectiveness of its enhanced interrogation techniques.

- The CIA rarely reprimanded or held personnel accountable for serious or significant violations, inappropriate activities, and systematic and individual management failures.

- The CIA marginalized and ignored numerous internal critiques, criticisms, and objections concerning the operation and management of the CIA's Detention and Interrogation Program.

- The CIA's Detention and Interrogation Program was inherently unsustainable and had effectively ended by 2006 due to unauthorized press disclosures, reduced cooperation from other nations, and legal and oversight concerns.

- The CIA's Detention and Interrogation Program damaged the United States' standing in the world and resulted in other significant monetary and non-monetary costs.

According to the report, at least 26 of the 119 prisoners (22%) held by the CIA were subsequently found by the CIA to have been improperly detained,[160] many having also experienced torture.[161] Of the 119 known detainees, at least 39 were subjected to the CIA enhanced interrogation techniques.[160] In at least six cases, the CIA used torture on suspects before evaluating whether they would be willing to cooperate.[160][162]

European Court of Human Rights decisions

editOn July 24, 2014, the European Court of Human Rights ruled that Poland violated the European Convention on Human Rights when it cooperated with the US government, allowing the CIA to hold and torture Abu Zubaydah and Abd al-Rahim al-Nashiri on its territory in 2002–2003. The court ordered the Polish government to pay each of the men 100,000 euros in damages. It also awarded Abu Zubaydah 30,000 euros to cover his costs.[163][164]

On May 31, 2018, the ECHR ruled that Lithuania and Romania also violated the rights of Abu Zubaydah and Abd al-Rahim al-Nashiri in 2003–2005 and in 2005–2006 respectively, and Lithuania and Romania were ordered to pay 100,000 euros in damages each to Abu Zubaydah and Abd al-Nashiri.[165][166][167]

See also

edit- Area 51

- Bright Light (CIA)

- Camp 1391

- Claudio Fava – former MEP that led an investigation into the role of the EU concerning black sites

- Enemy combatant

- Enhanced interrogation techniques

- Essential Killing, 2010 film

- Extrajudicial prisoners of the United States

- Extraordinary rendition by the United States

- Forced disappearance

- Geneva Conventions

- Guantanamo Bay detention camp

- Political prisoner

- Prisoner of war

- Rendition

- Rendition aircraft

- Salt Pit, a.k.a. "Dark Prison", near Kabul.

- Torture chamber

- United Nations Convention Against Torture

References

edit- ^ Grandin, Greg (February 25, 2013). "The Latin American Exception: How a Washington Global Torture Gulag Was Turned Into the Only Gulag-Free Zone on Earth". TRANSCEND Media Service. Archived from the original on May 28, 2013. Retrieved October 19, 2021.

- ^ "CIA Secret Detention and Torture". opensocietyfoundations.org. Archived from the original on February 20, 2013.

- ^ a b c "EU endorses damning report on CIA". BBC News. February 14, 2007. Archived from the original on July 10, 2018. Retrieved February 14, 2007.

- ^ a b c "20 Extraordinary Facts about CIA Extraordinary Rendition and Secret Detention". www.justiceinitiative.org. Retrieved July 2, 2024.

- ^ a b Priest, Dana (November 2, 2005). "CIA Holds Terror Suspects in Secret Prisons". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on January 21, 2011. Retrieved February 19, 2007.

- ^ "Bush: Top terror suspects to face tribunals". CNN. Associated Press. September 6, 2006. Archived from the original on September 6, 2006. Retrieved September 6, 2006.

- ^ "Bush admits to CIA secret prisons". BBC News. September 7, 2006. Archived from the original on November 12, 2014. Retrieved April 15, 2007.

- ^ a b "EU rendition report: Key excerpts". BBC News. February 14, 2007. Archived from the original on May 21, 2023. Retrieved August 5, 2024.

- ^ "Secret prisons: Obama's order to close 'black sites'". The Guardian. January 23, 2009. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved July 2, 2024.

- ^ DeYoung, Joby Warrick and Karen (January 23, 2009). "Obama Reverses Bush Policies On Detention and Interrogation". The Washington Post. ISSN 0190-8286. Retrieved July 2, 2024.

- ^ "UN experts point to widespread use of secret detention linked to counter-terrorism | UN News". news.un.org. January 26, 2010. Retrieved July 2, 2024.

- ^ a b "20 key findings about CIA interrogations". Washington Post. Retrieved July 2, 2024.

- ^ "European Court Condemns Poland in Historic Ruling on CIA 'Black Sites'". www.justiceinitiative.org. Retrieved July 2, 2024.

- ^ Williams, Carol (May 10, 2015). "Poland feels sting of betrayal over CIA 'black site'". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on January 22, 2021. Retrieved January 16, 2021.

- ^ Goldman, Adam (May 17, 2023). "The hidden history of the CIA's prison in Poland". Washington Post. ISSN 0190-8286. Retrieved July 2, 2024.

- ^ "Landmark rulings expose Romanian and Lithuanian complicity in CIA secret detention programme". Amnesty International. May 31, 2018. Retrieved July 2, 2024.

- ^ a b Gonyea, Don (September 6, 2006). "Bush Concedes CIA Ran Secret Prisons Abroad". All Things Considered. Retrieved August 5, 2024.

- ^ a b "Bush admits to CIA secret prisons". BBC. September 7, 2006. Archived from the original on November 12, 2014. Retrieved December 5, 2022.

- ^ Report on the Treatment of Fourteen 'High Value Detainees' in CIA Custody (PDF) (Report). International Committee of the Red Cross. February 14, 2007. Archived from the original (PDF) on April 19, 2009. Retrieved April 16, 2009.

- ^ Ross, James (September 2007). "Black Letter Abuse: the US Legal Response to torture since 9/11" (PDF). International Review of the Red Cross. 89 (867): 561–590. doi:10.1017/S1816383107001282. S2CID 145217797. Archived (PDF) from the original on August 9, 2017. Retrieved October 10, 2021.

- ^ Danner, Mark (April 9, 2009). "US Torture: Voices from the Black Sites". New York Review of Books. 56 (6). Archived from the original on March 4, 2010. Retrieved September 29, 2012.

- ^ Danner, Mark (March 14, 2009). "Opinion | Tales from Torture's Dark World". The New York Times. Retrieved August 5, 2024.

- ^ Marc Ambinder, The 5 secret code words that define our era, February 26, 2013

- ^ Kirk, Michael. "Top Secret America". Frontline. PBS. Retrieved May 1, 2013.

- ^ Dana Priest, Covert CIA Program Withstands New Furor, December 30, 2005

- ^ Marc Ambinder, In Released Docs, Government Reveals A Classified Term, September 1, 2009

- ^ Marc Ambinder & D.B. Grady, Deep State, Inside the Government Secrecy Industry, 2013, p. 166-167.

- ^ "Secret CIA jail claims rejected". BBC News. June 7, 2006. Archived from the original on June 9, 2021. Retrieved August 16, 2021.

- ^ Ross, Brian; Esposito, Richard (December 5, 2005). "Sources Tell ABC News Top Al Qaeda Figures Held in Secret CIA Prisons". ABC News. Archived from the original on December 19, 2005. Retrieved April 15, 2007.

- ^ Fisher, William (May 20, 2006). "US Groups Hail Censure of Washington's 'Terror War'". Inter Press Service. Archived from the original on June 19, 2006.

- ^ Committee Against Torture (May 18, 2006). "Consideration of Reports Submitted by States Parties Under Article 19 of the Convention: Conclusions and recommendations of the Committee against Torture" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on June 3, 2006.

- ^ Rupert Cornwell, 'Rendition' does not involve torture, says Rice Archived December 8, 2005, at the Wayback Machine The Independent on December 6, 2005

- ^ Bronwen Maddox, Tough words from Rice leave loopholes Archived 2008-02-10 at the Wayback Machine, The Times on December 6, 2005

- ^ "Bush acknowledges secret CIA prisons". NBC. September 5, 2006. Archived from the original on May 12, 2024. Retrieved May 11, 2024.

- ^ Priest, Dana; Gellman, Barton (December 26, 2002). "U.S. Decries Abuse but Defends Interrogations". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on July 4, 2008.

- ^ Cloud, David S. (April 23, 2006). "Colleagues Say C.I.A. Analyst Played by Rules". The New York Times. Archived from the original on June 17, 2013. Retrieved April 26, 2010.

- ^ Smith, R. Jeffrey; Linzer, Dafna (April 24, 2006). "Dismissed CIA Officer Denies Leak Role". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on March 14, 2021.

- ^ Smith, R. Jeffrey (May 14, 2006). "Fired Officer Believed CIA Lied to Congress" Archived 2021-01-12 at the Wayback Machine. The Washington Post.

- ^ Bush, George W. (September 29, 2006). "Remarks by the President on the Global War on Terror" Archived 2017-12-30 at the Wayback Machine. The White House

- ^ Morgan, David (July 20, 2007). "Bush orders CIA to comply with Geneva Conventions". Reuters. Archived from the original on January 10, 2009. Retrieved July 20, 2007.

- ^ a b Marty, Dick (January 22, 2006). "Information memorandum II on the alleged secret detentions in Council of Europe state" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on May 24, 2006. Retrieved August 16, 2021.

- ^ Barnes, Robert (October 9, 2007). "Court Declines Case of Alleged CIA Torture Victim". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on July 25, 2008. Retrieved October 9, 2007.

- ^ Walsh, Declan (November 24, 2009). "The mystery of Dr Aafia Siddiqui". guardian.co.uk. Archived from the original on April 13, 2010. Retrieved July 3, 2013.

- ^ a b Hughes, C. J. (February 3, 2010). "Aafia Siddiqui Guilty of Shooting at Americans in Afghanistan". The New York Times. Archived from the original on February 10, 2010. Retrieved April 10, 2010.

- ^ a b "Aafia Siddiqui Found Guilty in Manhattan Federal Court of Attempting to Murder U.S. Nationals in Afghanistan and Six Additional Charges" (PDF) (Press release). United States Attorney Southern District of New York. February 3, 2010. Archived from the original (PDF) on February 16, 2010. Retrieved February 14, 2010.

- ^ Pilkington, Ed (February 4, 2010). "Pakistani scientist found guilty of attempted murder of U.S. agents". The Guardian. London. Archived from the original on April 18, 2010. Retrieved April 10, 2010.

- ^ Murphy, Dan (September 23, 2010). "Aafia Siddiqui, alleged Al Qaeda associate, gets 86-year sentence". The Christian Science Monitor. Archived from the original on September 26, 2010. Retrieved September 24, 2010.

- ^ "'Rendition' and secret detention: A global system of human rights violations" Archived 2014-10-12 at the Wayback Machine, Amnesty International, January 1, 2006

- ^ a b c d e f "The CIA closed its original 'black site' years ago. But its legacy of torture lives on in Thailand". Los Angeles Times. April 22, 2018. Retrieved July 2, 2024.

- ^ Ross, Sherwood (April 1, 2010). "More Than Two-Dozen Countries Complicit In US Torture Program". The Public Record. Archived from the original on January 8, 2020. Retrieved August 16, 2021.

- ^ a b c d "CIA director Gina Haspel's Thailand torture ties". May 3, 2018. Retrieved July 2, 2024.

- ^ Nanuam, Wassana (August 27, 2018). "Ex-US base 'not secret prison'". Bangkok Post. Retrieved August 27, 2018.

- ^ "Time to come clean on secret CIA prison" (Opinion). Bangkok Post. May 27, 2018. Archived from the original on September 14, 2022. Retrieved May 27, 2018.

- ^ "Thaksin denies Thailand had 'CIA secret prison'". Bangkok Post.[dead link]

- ^ Crispin, Shawn (January 25, 2008). "US and Thailand: Allies in Torture". Asia Times. Archived from the original on November 10, 2014. Retrieved September 29, 2012.

- ^ "Council of Europe Parliamentary Assembly". Assembly.coe.int. Archived from the original on September 24, 2012. Retrieved September 29, 2012.

- ^ "Suspicion over Thai 'black ops' site". Sydney Morning Herald. November 5, 2005. Archived from the original on April 26, 2018. Retrieved April 27, 2018.

- ^ Rosenberg, Carol; Barnes, Julian E. (June 3, 2022). "Gina Haspel Observed Waterboarding at C.I.A. Black Site, Psychologist Testifies". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved July 3, 2024.

- ^ "CIA director Gina Haspel's Thailand torture ties". BBC News. May 4, 2018. Archived from the original on May 15, 2018. Retrieved May 15, 2018.

- ^ "The Salt Pit, CIA Interrogation Facility outsitde Kabul". GlobalSecurity.org. Archived from the original on August 24, 2021. Retrieved August 16, 2021.

- ^ a Priest, Dana (December 26, 2002). "U.S. Decries Abuse but Defends Interrogations 'Stress and Duress' Tactics Used on Terrorism Suspects Held in Secret Overseas Facilities". The Washington Post. pp. A01. Archived from the original on July 4, 2008.

- ^ U.S. Operated Secret ‘Dark Prison’ in Kabul (Human Rights Watch, 19–12–2005) Archived February 3, 2006, at the Wayback Machine, retrieved on May 4, 2009

- ^ Risen, James; Shanker, Thom (December 18, 2003). "Hussein Enters Post 9/11 Web of U.S. Prisons". The New York Times. p. A1.

- ^ White, Josh (March 11, 2005). "Army, CIA Agreed on 'Ghost' Prisoners". The Washington Post. pp. A16. Archived from the original on January 25, 2011. Retrieved August 16, 2021.

- ^ "Sexual abuse rife at UAE-run jails in Yemen, prisoners claim". the Guardian. Associated Press. June 20, 2018. Archived from the original on September 6, 2021. Retrieved August 16, 2021.

- ^ "Disappearances and torture in southern Yemen detention facilities must be investigated as war crimes". www.amnesty.org. July 12, 2018. Archived from the original on January 2, 2020. Retrieved August 13, 2019.

- ^ "Inside numerous secret prisons in Yemen, the UAE tortures and the U.S. interrogates detainees: Re..." June 25, 2017. Archived from the original on July 3, 2018. Retrieved August 16, 2021.

- ^ "HRW: UAE backs torture and disappearances in Yemen". www.aljazeera.com. Archived from the original on August 1, 2018. Retrieved August 16, 2021.

- ^ "Amnesty urges probe into report of UAE torture in Yemen". www.aljazeera.com. Archived from the original on August 1, 2018. Retrieved August 16, 2021.

- ^ "UAE runs 'horrific network of torture' in secret Yemen prisons: report". Daily Sabah. Associated Press. June 22, 2017. Archived from the original on July 3, 2018. Retrieved August 16, 2021.

- ^ "NGO calls for closing UAE's 'secret prisons' in Yemen". Anadolu Agency. Archived from the original on December 28, 2020. Retrieved December 28, 2020.

- ^ "The UAE and Saudi Arabia Supervise the Arrest and Torture of Dozens of Yemenis". YouTube. December 26, 2020. Archived from the original on August 16, 2021. Retrieved December 26, 2020.

- ^ "The #UAE an #SaudiArabia supervise the arrest and torture of dozens of Yemenis". Twitter. Archived from the original on December 26, 2020. Retrieved December 26, 2020.

- ^ "Authorities in Mukalla must free those being arbitrarily detained in Al Munawara Central Prison". Mwatana. April 11, 2021. Archived from the original on April 11, 2021. Retrieved April 11, 2021.

- ^ Huizinga, Johan (November 25, 2005). "Is Europe being used to hold CIA detainees?". Radio Netherlands. Archived from the original on June 29, 2012.

- ^ "CIA Prisons Moved To North Africa?". CBS News. December 13, 2005. Archived from the original on June 15, 2013. Retrieved August 16, 2021.

- ^ "United States of America / Below the radar: Secret flights to torture and 'disappearance'". Amnesty International. April 5, 2006. Archived from the original on April 10, 2006.

- ^ Burke, Jason (June 13, 2004). "Secret world of US jails". The New York Observer. London. Archived from the original on November 15, 2007. Retrieved August 16, 2021.

- ^ a b c "Secret prisons: Obama's order to close 'black sites'". The Guardian. London. January 23, 2009. Archived from the original on January 26, 2009. Retrieved January 23, 2009.

- ^ "United States of America / Yemen: Secret Detention in CIA 'Black Sites'". yubanet.com. November 8, 2005. Archived from the original on November 24, 2005.

- ^ "Developments in the British Indian Ocean Territory". Hansard. June 21, 2004. Archived from the original on May 13, 2006. Retrieved June 1, 2006.

- ^ Cobain, Ian (January 30, 2015). "CIA interrogated suspects on Diego Garcia, says Colin Powell aide". The Guardian. Archived from the original on February 27, 2015. Retrieved February 27, 2015.

- ^ "Terror suspects were interrogated on Diego Garcia, US official admits". Daily Telegraph. Press Association. January 30, 2015. Archived from the original on February 28, 2015. Retrieved February 27, 2015.

- ^ "Source: US Used UK Isle for Interrogations". Time. July 31, 2008. Archived from the original on August 5, 2008.

- ^ Staff writers (February 21, 2008). "UK apology over rendition flights". BBC News. Archived from the original on May 21, 2009. Retrieved February 21, 2008.

- ^ a b c d Dombey, Daniel (January 10, 2006). "CIA faces new secret jails claim". Financial Times.

- ^ "Swiss hunt leak on CIA prisons". The Chicago Tribune. January 12, 2006. Archived from the original on May 11, 2024. Retrieved May 11, 2024.

- ^ "Swiss intercept fax on secret CIA jails". Vive le Canada. January 10, 2006. Archived from the original on February 21, 2008. Retrieved January 21, 2006.

- ^ "Swiss paper claims proofs of secret US torture camp". Australian Broadcasting Corporation. January 12, 2006. Archived from the original on August 16, 2021. Retrieved August 16, 2021.

- ^ "Report: CIA had prisons in Poland". CNN. June 8, 2007. Archived from the original on June 12, 2007.

- ^ Verseck, Keno (April 22, 2015). "Folter in Rumänien: Ex-Staatschef Iliescu gibt Existenz von CIA-Gefängnis zu" [Torture in Romania: Former Head of State Iliescu Acknowledges Existence of CIA Prison]. Der Spiegel (in German). Hamburg, Germany: Spiegel-Verlag. Archived from the original on April 23, 2015. Retrieved April 22, 2015.

- ^ "Was Romanian base a CIA prisoner site?". NBC News. February 24, 2008.

- ^ "Ukraine denies hosting secret CIA prisons". United Press International. March 13, 2006. Archived from the original on October 24, 2007. Retrieved August 16, 2021.

- ^ Shane, Scott (June 22, 2008). "Inside a 9/11 Mastermind's Interrogation". The New York Times. Archived from the original on April 2, 2019. Retrieved August 16, 2021.

- ^ Easton, Adam (September 6, 2008). "Polish agents tell of CIA jails". BBC News. Archived from the original on July 15, 2021. Retrieved August 16, 2021.

- ^ "Rights group: US won't cooperate with Polish probe of CIA prisons". Monsters and Critics. December 28, 2010. Archived from the original on August 31, 2011.

- ^ Osborn, Andrew (November 21, 2009). "Lithuania pinpoints site of alleged secret CIA prison". The Age. Melbourne. Archived from the original on December 27, 2009. Retrieved December 15, 2009.

- ^ "Lithuania investigates claim it ran secret prison". The Irish Times. November 21, 2009. Archived from the original on October 19, 2012. Retrieved December 15, 2009.

- ^ "Valstietis.lt". www.valstietis.lt. Archived from the original on May 9, 2022. Retrieved May 13, 2022.

- ^ "Senate report 'proves Lithuania hosted CIA jail': detainee's lawyers". Reuters. September 17, 2015. Archived from the original on November 20, 2015. Retrieved June 30, 2017.

- ^ "Jail for sale: Lithuania to put former CIA black site up for auction". Washington Post. January 26, 2022. Archived from the original on January 26, 2022. Retrieved January 27, 2022.

- ^ Day, Matthew (December 10, 2014). "Polish president admits Poland agreed to host secret CIA 'black site'". Daily Telegraph. Archived from the original on December 17, 2014. Retrieved December 17, 2014.

- ^ Posner, Michael (2004). "Letter to Secretary Rumsfeld" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on February 18, 2006 – via humanrightsfirst.org.

- ^ "John Walker Lindh Profile: The case of the Taliban American". CNN. Archived from the original on November 28, 2005. Retrieved November 29, 2005.

- ^ "Myers: Intelligence might have thwarted attacks". CNN. January 9, 2002. Archived from the original on December 13, 2006.

- ^ Priest, Dana (December 27, 2004). "Jet Is an Open Secret in Terror War". The Washington Post. pp. A01.[dead link]

- ^ Tim (December 11, 2004). "CIA Torture Jet sold in attempted cover up". Melbourne Indymedia. Archived from the original on March 17, 2005.

- ^ Grey, Stephen (November 14, 2004). "Details of US 'torture by proxy flights' emerge". Not In Our Name. Archived from the original on January 13, 2007.

- ^ Brooks, Rosa (November 5, 2005). "Torture: It's the new American way". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on April 27, 2006. Retrieved August 16, 2021.

- ^ Duncan Campbell, Richard Norton-Taylor (June 2, 2008). "US accused of holding terror suspects on prison ships". The Guardian. London. Archived from the original on May 18, 2023. Retrieved June 1, 2008.

- ^ Duncan Campbell, Richard Norton-Taylor (June 2, 2008). "Prison ships, torture claims, and missing detainees". The Guardian. London. Archived from the original on September 2, 2013. Retrieved June 1, 2008.

- ^ "Revealed: the full story of the Guantanamo Britons The Observer's David Rose hears the Tipton Three give a harrowing account of their captivity in Cuba". The Guardian. London. March 14, 2004. Archived from the original on March 18, 2023. Retrieved April 26, 2010.

- ^ Priest, Dana (November 2, 2005). "CIA Holds Terror Suspects in Secret Prisons". CNN. pp. A01. Archived from the original on January 21, 2011. Retrieved August 16, 2021.

- ^ "'Enduring Freedom:' Abuses by U.S. Forces in Afghanistan". Human Rights Watch. March 2004. Archived from the original on April 15, 2016. Retrieved August 16, 2021.

- ^ Browne, Vincent (June 24, 2011). "Abductions via Shannon". politico.ie. Archived from the original on January 13, 2016. Retrieved October 26, 2015.

- ^ Priest, Dana (November 1, 2005). "CIA Holds Terror Suspects in Secret Prisons". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on June 11, 2006. Retrieved April 15, 2007.

- ^ a b "Transcript of interview of Andrea Mitchell, Mitch McConnell, Chuck Schumer, Bill Bennett, John Harwood, Dana Priest and William Safire". NBC News. June 2, 2006. Archived from the original on October 22, 2013. Retrieved April 15, 2007.

- ^ "The Consequences of Covering Up". FAIR. November 4, 2005. Archived from the original on September 8, 2012. Retrieved August 16, 2021.

- ^ Whitlock, Craig (November 3, 2005). "U.S. Faces Scrutiny Over Secret Prisons". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on November 7, 2012. Retrieved April 15, 2007.