Burnley (/ˈbɜːrnli/) is a town and the administrative centre of the wider Borough of Burnley in Lancashire, England, with a 2021 population of 78,266.[2] It is 21 miles (34 km) north of Manchester and 20 miles (32 km) east of Preston, at the confluence of the River Calder and River Brun.

| Burnley | |

|---|---|

| Town | |

Clockwise from top left: Burnley Town Hall; St Peter's Church; Belle Vue Mill; View of eastern Burnley and the Forest of Pendle; St James's Street in the town centre | |

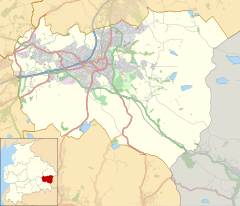

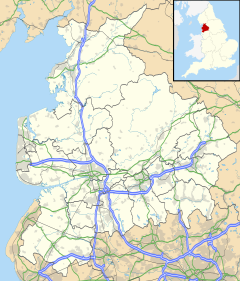

Location within Lancashire | |

| Area | 15.82 km2 (6.11 sq mi) [1] |

| Population | 78,266 (2021 Census) |

| • Density | 4,947/km2 (12,810/sq mi) |

| OS grid reference | SD836326 |

| • London | 181 mi (291 km) SSE |

| District | |

| Shire county | |

| Region | |

| Country | England |

| Sovereign state | United Kingdom |

| Post town | BURNLEY |

| Postcode district | BB10-BB12 |

| Dialling code | 01282 |

| Police | Lancashire |

| Fire | Lancashire |

| Ambulance | North West |

| UK Parliament | |

| Website | burnley |

The town is located near the countryside to the south and east, with the towns of Padiham and Brierfield to the west and north respectively. It has a reputation as a regional centre of excellence for the manufacturing and aerospace industries.

The town began to develop in the early medieval period as a number of farming hamlets surrounded by manor houses and royal forests, and has held a market for more than 700 years. During the Industrial Revolution it became one of Lancashire's most prominent mill towns; at its peak, it was one of the world's largest producers of cotton cloth and a major centre of engineering.

Burnley has retained a strong manufacturing sector, and has strong economic links with the cities of Manchester and Leeds, as well as neighbouring towns along the M65 corridor. In 2013, in recognition of its success, it received an Enterprising Britain award from the UK Government as the Most Enterprising Area in the UK.[3] For the first time in more than 50 years, a direct train service now operates between the town's Manchester Road railway station and Manchester's Victoria station and onward to Wigan Wallgate via the restored Todmorden Curve, which opened in May 2015.

History

editToponymy

editThe name Burnley is believed to have been derived from Brun Lea, meaning "meadow by the River Brun".[4] Various other spellings have been used: Bronley (1241), Brunley (1251) and commonly Brumleye (1294)[5]

Origins

editStone Age flint tools and weapons have been found on the moors around the town,[4] as have numerous tumuli, stone circles, and some hill forts (see: Castercliff, which dates from around 600 BC). Modern-day Back Lane, Stump Hall Lane and Noggarth Road broadly follow the route of a classic ridgeway running east–west to the north of the town, suggesting that the area was populated during pre-history and probably controlled by the Brigantes.

Limited coin finds indicate a Roman presence, but no evidence of a settlement has been found in the town. Gorple Road (running east from Worsthorne) appears to follow the route of a Roman road that may have crossed the present-day centre of town, on the way to the fort at Ribchester. It has been claimed that the nearby earthworks of Ring Stones Camp (53°47′35″N 2°10′26″W / 53.793°N 2.174°W),[6] Twist Castle (53°48′00″N 2°10′16″W / 53.800°N 2.171°W)[7] and Beadle Hill (53°48′11″N 2°10′08″W / 53.803°N 2.169°W)[8] are of Roman origin, but little supporting archaeological information has been published.

Following the Roman period, the area became part of the kingdom of Rheged, and then the kingdom of Northumbria. Local place-names Padiham and Habergham show the influence of the Angles, suggesting that some had settled in the area by the early 7th century;[4] sometime later the land became part of the hundred of Blackburnshire.

There is no definitive record of a settlement until after the Norman conquest of England. In 1122, a charter granted the church of Burnley to the monks of Pontefract Abbey.[4] In its early days, Burnley was a small farming community, gaining a corn mill in 1290,[9] a market in 1294, and a fulling mill in 1296. At this point, it was within the manor of Ightenhill, one of five that made up the Honor of Clitheroe, then a far more significant settlement, and consisted of no more than 50 families. Little survives of early Burnley apart from the Market Cross, erected in 1295, which now stands in the grounds of the old grammar school.[4]

Over the next three centuries, Burnley grew in size to about 1,200 inhabitants by 1550, still centred around the church, St Peter's, in what is now known as "Top o' th' Town". Prosperous residents built larger houses, including Gawthorpe Hall in Padiham and Towneley Hall.

In 1532, St Peter's Church was largely rebuilt. Burnley's grammar school was founded in 1559, and moved into its own schoolhouse next to the church in 1602. Burnley began to develop in this period into a small market town, with a population of not more than 2,000 by 1790.[10] It is known that weaving was established in the town by the middle of the 18th century, and in 1817 a new Market House was built. The town continued to be centred on St Peter's Church, until the market was moved to the bottom of what is today Manchester Road, at the end of the 19th century.[4]

Industrial Revolution

editIn the second half of the 18th century, the manufacture of cotton began to replace wool. Burnley's earliest known factories – dating from the mid-century – stood on the banks of the River Calder, close to where it is joined by the River Brun, and relied on water power to drive the spinning machines. The first turnpike road through the area now known as Burnley was begun in 1754, linking the town to Blackburn and Colne eventually leading to the area of Brun Lea developing into a town, and by the mid 19th century, there were daily stagecoach journeys to Blackburn, Skipton and Manchester, the latter taking just over two hours.[4]

The 18th century also saw the rapid development of coal mining on the Burnley Coalfield: the drift mines and shallow bell-pits of earlier centuries were replaced by deeper shafts, meeting industrial as well as domestic demand in Nelson, Colne and Padiham, and by 1800 there were over a dozen pits in the modern-day centre of the town alone.[4]

The arrival of the Leeds and Liverpool Canal in 1796 made possible transportation of goods in bulk, bringing a huge boost to the area's economy and the town of Burnley was born. Dozens of new mills were constructed, along with many foundries and ironworks that supplied the cotton mills and coal mines with machinery and cast and wrought iron for construction. The town became renowned for its mill-engines, and the Burnley Loom was recognised as one of the best in the world.

A permanent military presence was established in the town with the completion of Burnley Barracks in 1820.[11]

Disaster struck Burnley in 1824, when its only local bank, Holgate's Bank, collapsed,[12][13] forcing the closure of some of the largest mills. This was followed by a summer drought, which caused serious problems for many of the other mills, leading to high levels of unemployment and possibly contributing to the national Panic of 1825.[citation needed]

By 1830, there were 32 steam engines in cotton mills throughout the rapidly expanding town,[4] an example of which, originally installed at Harle Syke Mill, is on display in the Science Museum in London.[14]

Around 1840, a traveller described the town as ugly, stating that: "parts of it were so situated that good architectural effects might have been obtained had the disposition and the resources co-existed".[10]

The Great Famine of Ireland led to an influx of Irish families during the 1840s, who formed a community in one of the poorest districts. At one time, the Park District (modern-day town centre, around Parker St.) was known as Irish Park.

In 1848, the East Lancashire Railway Company's extension from Accrington linked the town to the nation's nascent railway network for the first time. This was another significant boost to the local economy and, by 1851, the town's population had reached almost 21,000.[4]

The Burnley Building Society, incorporated in Burnley in 1850, was, by 1911, not only 'by far the largest in the County of Lancashire... but the sixth in magnitude in the kingdom'.[15]

The Cotton Famine of 1861–1865, caused by the American Civil War, was again disastrous for the town. However, the resumption of trade led to a quick recovery and, by 1866, the town was the largest producer of cotton cloth in the world.[16] By the 1880s, the town was manufacturing more looms than anywhere in the country.[17]

In 1871, the population was 44,320, and had grown to 87,016 by 1891.[10] Burnley Town Hall, designed by Holton and Fox of Dewsbury, was built between 1885 and 1888.[10]

The Burnley Electric Lighting Order was granted in 1890, giving Burnley Corporation (which already controlled the supply of water and the making and sale of gas) a monopoly in the generation and sale of electricity in the town. The building of the coal-powered Electricity Works, in Grimshaw Street, began in 1891, close to the canal (the site of the modern-day Tesco supermarket) and the first supply was achieved on 22 August 1893, initially generating electricity for street lighting.[18]

The start of the 20th century saw Burnley's textile industry at the height of its prosperity. By 1901 there were 700,000 spindles and 62,000 looms at work in the textile industry. Other industries at that time included: brass and iron foundries, rope works, calico printing works, tanneries, paper mills, collieries and corn mills and granaries.[10] By 1910, there were approximately 99,000 power looms in the town,[19] and it reached its peak population of over 100,000 in 1911.[20] By 1920, the Burnley and District Weavers', Winders' and Beamers' Association had more than 20,000 members.[21] However, the First World War heralded the beginning of the collapse of the English textiles industry and the start of a steady decline in the town's population.[20] The Bank Parade drill hall was completed in the early 20th century.[22]

There is a total of 191 listed buildings in Burnley – one Grade I (Towneley Hall), two Grade II* (St Peter's Church and Burnley Mechanics) and 188 Grade II.[23]

World Wars

editOver 4000 men from Burnley were killed in the First World War, about 15 per cent of the male working-age population.[24]

250 volunteers, known as the Burnley Pals, made up Z Company of 11th Battalion, the East Lancashire Regiment, a battalion that as a whole became known by the far more famous name of the Accrington Pals. Victoria Crosses were awarded to two soldiers from the town, Hugh Colvin and Thomas Whitham, along with a third to resident (and only son of the chief constable) Alfred Victor Smith. In 1926 a memorial to the fallen was erected in Towneley Park, funded by Caleb Thornber, former mayor and alderman of the borough to ensure the sacrifice of the men lost was commemorated. The local school of art created pages of vellum with the names of the fallen inscribed. These were framed in a rotating carousel in Towneley Hall for visitors to see. There were 2000 names inscribed – less than half the number of actual casualties.

The Burnley Justices had delegated their authority to determine which pictures could be shown in local cinemas to a panel of three justices. In a judicial review in 1916 this was found to be an unlawful delegation of their authority.[25]

During the Second World War, Burnley largely escaped the Blitz, with the only Luftwaffe bomb to known to have fallen within the town landing near the conservatory at Thompson Park on 27 October 1940.[26] In early 1941 a network of five Starfish site bombing decoys were established in the rural areas near Burnley, designed to protect Accrington. A site was located near Crown Point in Habergham Eaves with two on Hameldon Hill, and others in Worsthorne-with-Hurstwood and near Haslingden.[27]

On 6 May 1941, a stick of eight bombs straddled houses around Rossendale Avenue on the southern edge of town, causing only minor damage. On the night of 12 October the control shelter at the Starfish site near Crown Point suffered a direct hit, killing Aircraftman L R Harwood, and severely injuring four other men.[28][29]

Although the blackout was enforced, most of the aircraft in the sky above the town would have been friendly and on training missions, or returning to the factories for maintenance. Aircraft crashes did occur, however: In September 1942 a P-38 Lightning from the 14th Fighter Group USAAF crashed near Cliviger, and Black Hameldon Hill claimed a Halifax from No. 51 Squadron RAF in January 1943, and also a B-24 Liberator from the 491st Bombardment Group USAAF in February 1945.[30] Lucas Industries set up shadow factories, producing a wide range of electrical parts for the war effort. Notably they were involved with the Rover Company's failed attempts (and Rolls-Royce's later successful ones) to produce Frank Whittle's pioneering jet engine design, the W.2 (Rolls-Royce Welland) in Barnoldswick. Magnesium Elektron's factory in Lowerhouse became the largest magnesium production facility in Britain.[31] An unexpected benefit of the conflict for the residents of Burnley occurred in 1940. The Old Vic Theatre Company and the Sadler's Wells Opera and Ballet Companies moved from London to the town's Victoria Theatre.

For their actions during the war, two Distinguished Service Orders and eight Distinguished Conduct Medals, along with a large number of lesser awards, were awarded to servicemen from the town. Burnley's main war memorial stands in Place de Vitry sur Seine next to the central library.

Post-Second World War

editThe Queen, together with Prince Philip, first visited the town as well as Nelson and the Mullard valve factory at Simonstone near Padiham in 1955.[32]

There were widespread celebrations in the town in the summer of 1960, when Burnley FC won the old first division to become Football League champions.

The Queen paid a second official visit to the town in summer 1961, marking the 100th anniversary of Burnley's borough status. The rest of the decade saw large-scale redevelopment in the town. Many buildings were demolished including the market hall, the cattle market, the Odeon cinema and thousands of mainly terraced houses. New construction projects included the Charter Walk shopping centre, Centenary Way and its flyover, the Keirby Hotel, a new central bus station, a large scale housing development known as Trafalgar Gardens, and a number of office blocks. The town's largest coal mine, Bank Hall Colliery, closed in April 1971 resulting in the loss of 571 jobs. The area of the mine has been restored as a park.[33]

In 1980 Burnley was connected to the motorway network, through the construction of the first and second sections of the M65. Although the route, next to the railway and over the former Clifton colliery site, was chosen to minimise the clearance of occupied land, Yatefield, Olive Mount and Whittlefield Mills, Burnley Barracks, and several hundred more terrace houses had to be demolished. Unusually this route passed close to the town centre and had a partitioning effect on the districts of Gannow, Ightenhill, Whittlefield, Rose Grove and Lowerhouse to the north. The 1980s and 1990s saw massive expansion of Ightenhill and Whittlefield. Developers such as Bovis, Barratt and Wainhomes built large housing estates, predominantly on greenfield land.

In summer 1992, the town came to national attention following rioting on the Stoops and Hargher Clough council estates in the south west of the town.[34]

The millennium brought some improvement projects, notably the "Forest of Burnley" scheme,[35] which planted approximately a million trees throughout the town and its outskirts, and the creation of the Lowerhouse Lodges local nature reserve.[36]

In June 2001, during the 2001 England riots, the town again received national attention following a series of violent disturbances arising from racial tensions between some of its White and Asian residents.[37]

Governance

editBurnley was incorporated as a municipal borough in 1861, a Parliamentary Borough returning one member in 1867[10] and became, under the Local Government Act 1888, a county borough outside the administrative county of Lancashire. Under the Local Government Act 1972 Burnley's county borough status was abolished, and it was incorporated with neighbouring areas into the non-metropolitan district of Burnley.

Burnley has three tiers of government: Local government responsibilities are shared by Burnley Borough Council and Lancashire County Council; at a national level the town gives its name to a seat in the United Kingdom parliament. While the town itself is unparished, the rest of the borough has one further, bottom tier of government, the parish or town council.[38]

Borough Council

editBurnley Borough Council is currently governed by a multi-party coalition. The role of mayor is a ceremonial post which rotates annually and for 2020-21 is Wajid Khan[39] (Labour Party).

The borough comprises 15 wards, 12 of which – Bank Hall, Briercliffe, Brunshaw, Coal Clough with Deerplay, Daneshouse with Stoneyholme, Gannow, Lanehead, Queensgate, Rosegrove with Lowerhouse, Rosehill with Burnley Wood, Trinity, and Whittlefield with Ightenhill – fall within the town itself. The remaining three – Cliviger with Worsthorne, Gawthorpe, and Hapton with Park, cover the neighbouring town of Padiham and a number of villages.[40]

County Council

editLancashire County Council is currently controlled by the Conservative Party and has been since 2017. They have had only one other term in power between 2009 – 2013, the rest of the time from 1981, the council has been under Labour control. The borough is represented on the council in six divisions: Burnley Central East, Burnley Central West, Burnley North East, Burnley Rural, Burnley South West, and Padiham & Burnley West.[41]

National

editThe constituency of Burnley elects a single member of Parliament (MP). In the 2024 election Burnley elected Labour MP Oliver Ryan. Previously, in the general election in 2019, the town elected Antony Higginbotham, its first Conservative Party MP in over 100 years.[42] The constituency had been represented by MPs of the Labour Party since 1935, apart from 2010 – 2015, when it was represented by Gordon Birtwistle, a Liberal Democrat. Richard Shaw was the town's first MP in 1868. Arguably its most notable MP was former leader of the Labour Party and Nobel Peace Prize laureate Arthur Henderson.

Geography

editThe town lies in a natural three-forked valley at the confluence of the River Brun and the River Calder, surrounded by open fields, with wild moorland at higher altitudes. To the west of Burnley lie the towns of Padiham, Accrington and Blackburn, with Nelson and Colne to the north. The centre of the town stands at approximately 387 feet (118 m) above sea level and 30 miles (48 km) east of the Irish Sea coast.

Areas in the town include: Burnley Wood, Rose Hill, Healey Wood, Harle Syke, Haggate, Daneshouse, Stoneyholme, Burnley Lane, Heasandford, Brunshaw, Pike Hill, Gannow, Ightenhill, Whittlefield, Rose Grove, Habergham, and Lowerhouse. Although Reedley is considered to be a suburb of the town, it is actually part of the neighbouring borough of Pendle.

To the north west of the town, and home of the Pendle Witches, is the imposing Pendle Hill, which rises to 1,827 feet (557 m), beyond which lie Clitheroe and the Ribble Valley. To the south west, Hameldon Hill rises to 1,342 feet (409 m), on top of which are the Met Office north west England weather radar, a BBC radio transmitter, and a number of microwave communication towers. This site was the first place in the UK chosen for an unmanned weather radar, beginning operation in 1979; it is one of 18 that cover the British Isles.[43] Also since 2007 the three turbines of the Hameldon Hill wind farm have stood on its northern flank. To the east of the town lie the 1,677 feet (511 m) Boulsworth Hill and the moors of the South Pennines, and to the south, the Forest of Rossendale. On the hills above the Cliviger area to the south east of the town stands Coal Clough wind farm, whose white turbines are visible from most of the town. Built in 1992 amidst local controversy, it was one of the first wind farm projects in the UK. Nearby, the landmark RIBA Award-winning Panopticon Singing Ringing Tree, overlooking the town from the hills at Crown Point, was installed in 2006.[44]

Due to its hilly terrain and mining history, rural areas of modern Burnley encroach on the urban ones to within a mile of the town centre on the south, north west and north east.

The Pennine Way passes six miles (10 km) east of Burnley; the Mary Towneley Loop, part of the Pennine Bridleway, the Brontë Way and the Burnley Way offer riders and walkers clearly signed routes through the countryside immediately surrounding the town.

Burnley has a temperate maritime climate, with relatively cool summers and mild winters. There is regular but generally light precipitation throughout the year, contributing to a relatively high humidity level. While snowfall occasionally occurs during the winter months, the temperature is rarely low enough for it to build up on the ground in any quantity. The town is believed to be the first place in the UK where regular rainfall measurements were taken (by Richard Towneley, beginning in 1677).

| Climate data for Stonyhurst station (10 miles northwest of Burnley), elevation 115m, 1991-2020 normals | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Mean daily maximum °C (°F) | 6.73 (44.11) |

7.30 (45.14) |

9.36 (48.85) |

12.27 (54.09) |

15.44 (59.79) |

17.96 (64.33) |

19.59 (67.26) |

19.21 (66.58) |

16.91 (62.44) |

13.32 (55.98) |

9.65 (49.37) |

7.19 (44.94) |

12.94 (55.29) |

| Mean daily minimum °C (°F) | 1.85 (35.33) |

1.83 (35.29) |

2.96 (37.33) |

4.68 (40.42) |

7.25 (45.05) |

10.03 (50.05) |

11.97 (53.55) |

11.88 (53.38) |

9.85 (49.73) |

7.24 (45.03) |

4.32 (39.78) |

2.10 (35.78) |

6.35 (43.43) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 119.02 (4.69) |

108.51 (4.27) |

92.44 (3.64) |

65.44 (2.58) |

74.46 (2.93) |

90.15 (3.55) |

102.99 (4.05) |

113.58 (4.47) |

118.33 (4.66) |

135.22 (5.32) |

135.01 (5.32) |

159.36 (6.27) |

1,314.51 (51.75) |

| Average rainy days | 17.01 | 13.93 | 13.83 | 11.83 | 11.76 | 12.62 | 13.81 | 15.11 | 14.34 | 15.96 | 17.66 | 17.56 | 175.42 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 47.62 | 70.42 | 104.93 | 161.20 | 183.75 | 173.07 | 154.67 | 165.09 | 119.17 | 95.23 | 63.07 | 40.27 | 1,378.49 |

| Source: UK Climate Averages. Met Office. [1] | |||||||||||||

Demography

edit| The Borough of Burnley compared | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| UK Census 2011 | Burnley[45] | NW England[46] | England[47] |

| Total population | 87,059 | 7,052,177 | 53,012,456 |

| Foreign born | 7.7% | 8.2% | 13.8% |

| White | 87.4% | 90.2% | 85.4% |

| Asian | 10.7% | 5.5% | 7.1% |

| Black | 0.2% | 1.4% | 3.5% |

| Christian | 63.6% | 67.3% | 59.4% |

| Muslim | 9.9% | 5.1% | 5.0% |

| Hindu | 0.2% | 0.5% | 1.5% |

| No religion | 19.7% | 19.8% | 24.7% |

| Under 18 years old | 22.2% | 21.2% | 21.4% |

| Over 65 years old | 16.2% | 16.6% | 16.3% |

| Unemployed | 5.3% | 4.7% | 4.4% |

| Perm. sick / disabled | 7.0% | 5.6% | 4.0% |

The 2001 United Kingdom census showed a total resident population for the Burnley subdivision of the Burnley Built-up area of 73,021. The entire built-up area, which includes Nelson, Colne and Brierfield had a population of 149,796; for comparison purposes, this was about the same size as Oxford or Swindon in South England.[1] At that time the racial composition of the wider local government district (the Borough of Burnley) was 91.77% white and 7.16% South Asian or South Asian/British, predominantly from Bangladesh. The largest religious groups were Christian (74.46%) and Muslim (6.58%). 59.02% of adults between the ages of 16 and 74 were classed as economically active and in work.[48] In the 2011 United Kingdom census, these figures had changed to 87.4% white and 10.7% South Asian or South Asian/British, with 63.6% identifying as Christian and 9.9% Muslim.[45] The Burnley Built-up area, had a population of 149,422 according to the 2011 census.[49] The ONS annual population survey for the year Apr 2013–Mar 2014 showed that 63.1% of adults between the ages of 16 and 64 were classed as economically active.[50]

The majority of its Asian residents live in the neighbouring Daneshouse and Stoneyholme districts. In total, the size of its Asian community is much smaller than that in nearby towns such as Blackburn and Oldham.

In February 2010, the Lancashire Telegraph reported that Burnley topped Home Office figures for the highest number of burglaries per head in England and Wales between April 2008 – April 2009.[51] This claim (minus the dates) was repeated during one of the questions in the first of the televised 2010 general election debates.[52] However, in May 2010, the NPIA Local Crime Mapping System (believed to be the source of the data in the report) listed a 49.5% drop in this rate on the previous year.

Burnley has some of the lowest property prices in the country, with numerous streets appearing in the annual mouseprice.com most affordable streets in England and Wales report.[53][54][55][56] These streets are concentrated in areas of terrace housing in poorer neighbourhoods adjacent to the town centre. Between 2005 and 2010, approximately £65m of government funds was invested into these areas through the Elevate East Lancashire housing market renewal company (replaced by Regenerate Pennine Lancashire in 2010).

| Year | 1911 | 1921 | 1931 | 1939 | 1951 | 1961 | 1971 | 2001 | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Population | 106,322 | 103,157 | 89,258 | 85,400 | 84,987 | 80,559 | 76,489 | 73,021 | |||||||||||||

| [57] | |||||||||||||||||||||

Economy

editIn 2013, Burnley was awarded an Enterprising Britain award from the UK Government for being the 'Most Enterprising Area in the UK'.[58] This accolade subsequently received praise from the British Prime Minister, David Cameron,[59] and His Royal Highness, the Prince of Wales.[60]

A series of high-profile regeneration schemes, including: a direct rail link to Manchester,[61] an aerospace supply village[62] and multimillion-pound investment in the former Victorian industrial heartland through a project called 'On The Banks' [63] are radically transforming the economy of the Lancashire town. Although traditional manufacturing has been in decline in the town for several decades, high end advanced manufacturing remains very strong in the town. The Secretary of State for Business, Innovation and Skills, Vince Cable, said in 2013: "Burnley in the north of Lancashire is currently now booming economically on the back of manufacturing and proximity to the aerospace industry."[64] Cable praised the town again in 2014 saying: "If every other part of Britain was like Burnley we wouldn't be talking about a recession".[65]

The last deep coal mine, Hapton Valley Colliery, closed in February 1981[66] and the last steam-powered mill, Queen Street Mill, in 1982. Over the next two decades, Burnley's three largest manufacturers closed their factories: BEP in 1992, Prestige in July 1997 and Michelin in 2002.[67][68] The town has struggled to recover: its employment growth between 1995 and 2004 placed it 55th of England's 56 largest towns and cities,[69] and as of 2007 it was the 21st most deprived local authority (out of 354) in the United Kingdom.[70] In 2016, a study by the Joseph Rowntree Foundation put Rochdale, Burnley and Bolton at top of a list of the 74 largest UK cities and towns faring worst compared with UK trends.[71] 10.1% of its working age population currently claims incapacity benefit and ESA (national average 6.2%).[50] The largest employment sector in the town is now Health (21%), followed by Manufacturing (16%).[72]

Home shopping firm Shop Direct announced in January 2010 that it was to close its Burnley call centre with the loss of 450 jobs.[73] The company, which owns Littlewoods, Additions Direct, Very, Empire Stores and Marshall Ward, had been in the town for over 30 years, originally as Great Universal Stores but now known as GUS plc.

Modern economic developments have been industrial estates and business parks with the following currently in Burnley:[74] Heasandford, Rossendale Road, and Healeywood Industrial Estates; Network 65, Shuttleworth Mead, Smallshaw & Chestnut, Elm Street, and Gannow Business Parks; and Burnham Gate Trading Estate. A further large business park called Burnley Bridge, on a site near Hapton formerly belonging to Hepworth Plastics[75] has recently opened.

Key manufacturing employers today are in highly specialised fields: Safran Aircelle (aerospace), GE subsidiary Unison Engine Components (aerospace), AMS Neve (professional audio), and TRW Automotive and Futaba-Tenneco UK (automotive components).[76] In 2011 Gardner Aerospace, which made parts for the Eurofighter Typhoon, closed its site, with the loss of 120 jobs.[77] The town has also had a long association with Endsleigh Insurance Services, providing its main training facility and an important call centre. Endsleigh acquired a number of the former Burnley Building Society's properties in the town centre following its merger with the Provincial Building Society and subsequent merger with the Abbey National. It also hosts the head office of The Original Factory Shop chain. In 2004, the Lancashire Digital Technology Centre was opened by Sir Digby Jones on land formerly occupied by the Michelin factory, to provide support and incubation space for start-up technology companies.[78] The rest of the Michelin site has recently been opened as Innovation Drive, a new business park aimed at businesses in the Aerospace and Advanced Manufacturing supply chain.[79]

Continuing the town's historic association with fabric weaving is Ian Mankin Ltd, a company which manufactures high quality, natural woven fabrics and furnishings using only natural, recycled or certified organic fibres, at Ashfield Mill, Active Way, Burnley BB11 1BS, on the northern edge of the Weavers' Triangle.[80] The company also supplies fabrics to the Landmark Trust for use in their restoration of historic buildings across the UK.[81]

Burnley's main shopping area is St James Street, along with the nearby Charter Walk Shopping Centre. The YMCA claimed to have opened the largest charity shop in the UK in 2009, when they temporarily took over the former Woolworths store in the centre.[82] The shopping centre was sold in 2001 by Great Portland Estates to Sapphire Retail Fund, which was 50% owned by the Reuben Brothers. The centre was bought in March 2011 by Addington Capital following the 2010 collapse of Sapphire Retail Fund.[83] The centre incorporates the council-run market which is open four days a week.[84]

The town centre is home to a large number of high street multiples, along with other shops, including specialist food shops, independent record shops and an independent bookshop. On the edge of the town centre, there are four retail parks; there are also a number of mill shops. Plans have been in place since 2004 to construct a second town centre shopping centre, originally called 'The Oval'.[85] By the time a sufficient number of tenants had signed up to begin construction, the effects of the Great Recession cast doubts over the viability of the project. In early 2011, fresh plans were released for a considerably smaller scheme involving a cluster of retail units.[86] The site is now earmarked for a cinema and restaurants and is due to open in 2016[87] As well as Woolworths, the Great Recession led to the closure of T J Hughes, Miss Selfridge, and HMV but the project gained new high street names in large retail units including Next and River Island. The Market Square is currently under redevelopment with a number of retailers already moved in and more said to be 'signed up' to move in once the development is complete.[88]

The local brewery, Moorhouse's, which was founded in 1865, produces a range of award-winning beers and currently operates six pubs in the area. The Worsthorne Brewing Company produces a number of cask ales.[89] The Moonstone Brewery is operated within the "Ministry of Ale", Burnley's first Brewpub.[90] Reedley Hallows Brewery was launched in 2012 by the former Head Brewer at Moorhouses.

Religion

editSt Peter's Church, around which the town developed, dates from the 15th century, and is designated a Grade II* listed building by English Heritage. St Andrew's Church on Colne Road was built in 1866–67, to a design by J. Medland Taylor, and was restored in 1898 by the Lancaster architects Austin and Paley. It is designated a Grade II listed building. There are many other places of worship including those for Roman Catholics, Baptists, United Reformed Church, Methodists, Jehovah's Witnesses, Latter-Day Saints and Spiritualists.[91]

The chapel at Towneley Hall was the centre for Roman Catholic worship in Burnley until modern times.[92] Well before the Industrial Revolution, the town saw the emergence of many non-conformist churches and chapels. In 1891 the town was the location of the meeting which saw the creation of the Baptist Union of Great Britain and Ireland.

Burnley has ten mosques,[93] with the first purpose-built premises opening in 2009.[94] A total of 17 religious buildings or structures are designated as listed buildings – all Grade II by English Heritage.[95]

Landmarks

editLeeds and Liverpool Canal

editAlong the Burnley section of the canal are a number of notable features. The 3,675-foot (1,120 m) long and up to 60-foot (18.25 m) high almost perfectly level embankment, known as the Straight Mile, was built between 1796 and 1801 (before the invention of the steam shovel), to avoid the need for locks. It is regarded as one of the original seven wonders of the British waterways.[96] The much more modern (1980) Whittlefield motorway aqueduct is believed to be the first time a canal aqueduct was constructed over a motorway in the UK.

Weavers' Triangle

editThe Weavers' Triangle is an area west of Burnley town centre, consisting mostly of 19th-century industrial buildings, clustered around the Leeds and Liverpool Canal. The area has been identified as being of significant historical interest as the cotton mills and associated buildings encapsulate the social and economic development of the town and its weaving industry. From the 1980s, the area has been the focus of major redevelopment efforts.

Singing Ringing Tree

editThe Singing Ringing Tree is a wind powered sound sculpture resembling a tree, set in the landscape of the Pennines, 2 miles (3.2 km) south of Burnley town centre.

Completed in 2006, it is part of the series of four sculptures within the Panopticons arts and regeneration project created by the East Lancashire Environmental Arts Network (ELEAN). The project was set up to erect a series of 21st-century landmarks, or Panopticons (structures providing a comprehensive view), across East Lancashire as symbols of the renaissance of the area.

Designed by architects Mike Tonkin and Anna Liu of Tonkin Liu, the Singing Ringing Tree is a 9.8-foot (3 m) tall construction comprising pipes of galvanised steel, which harness the energy of the wind to produce a slightly discordant and penetrating choral sound covering a range of several octaves. Some of the pipes are primarily structural and aesthetic elements, while others have been cut across their width enabling the sound. The harmonic and singing qualities of the tree were produced by tuning the pipes according to their length by adding holes to the underside of each.

In 2007 the sculpture was one of 14 winners of the National Award of the Royal Institute of British Architects (RIBA) for architectural excellence.

Towneley Hall

editTowneley Hall was the home of the Towneley family for more than 500 years. Various family members were influential in the scientific, technological and religious developments which took place in the 17th and 18th centuries. The male line of the family died out in 1878 and in 1901 one of the daughters, Lady O'Hagan, sold the house together with 62 acres (25 ha) of land to Burnley Corporation.[97] The hall contains the 15th-century Whalley Abbey vestments and has its own chapel, which contains a finely carved altarpiece made in Antwerp in about 1525.

Transport

editBurnley is served by Junctions 9, 10 and 11 of the M65 motorway, which runs west to Accrington, Blackburn and Preston (where it connects to the M6), and northeast to Nelson and Colne. From the town centre, the A646 runs to Todmorden, the A679 to Accrington, the A671 to Clitheroe, and the A682 (a nearby rural section of which has been classified as Britain's most dangerous road)[98] south to Rawtenstall and north east to Nelson and the Yorkshire Dales. The A56 dual carriageway skirts the western edge of the town, linking to the M66 motorway heading towards Manchester and the M62.

Rail services to and from Burnley are provided by Northern. The town has four railway stations: Burnley Manchester Road, Burnley Central, Burnley Barracks and Rose Grove. A fifth station, Hapton, serves Padiham and Hapton to the west of the town, but inside the borough. Manchester Road station has an hourly semi-fast service west to Preston (the nearest station on the West Coast Main Line) and Blackpool North, and east to Leeds and York, whilst the Central and Barracks stations provide an hourly stopping service west to Blackpool South and Preston, and east to Nelson and Colne.

In May 2015, a direct train service to Manchester and onwards to Wigan Wallgate was reinstated. This provides a direct route to Manchester Victoria for the first time in over fifty years with the construction of a short section of track at the Hall Royd Junction of the Caldervale Line (known as the Todmorden curve). This has reduced the journey time between Burnley and central Manchester from around 1 hour and 25 minutes via Blackburn and Bolton and 1 hour and 4 minutes via Hebden Bridge to approximately 45 minutes via Todmorden and Rochdale where Metrolink tram connections via Oldham are possible.[99] In preparation for this new direct service a new Manchester Road station building including a ticket office and waiting rooms has recently been completed, which has made Manchester Road the new principal station for the town [100]

Burnley bus station, designed by Manchester-based SBS Architects,[101] won the UK Bus Award for Infrastructure in 2003.[102] The main bus operator is Burnley Bus Company, with Tyrer Bus operating some tendered town services. Other services are provided by First West Yorkshire (591/592 to Halifax), Blackburn Bus Company (152 to Preston) and Rosso (483 to Bury). National Express operates three coach services to London each day, and one to Birmingham. The X43 Witch Way service (operated by Burnley Bus Company) runs from Burnley to Manchester via Rawtenstall and Prestwich using a fleet of specially branded double-decker buses. The fastest journey takes about an hour.

Burnley does not have an airport, but there are four international airports within an hour's travel of the town: Manchester Airport at 31 miles (50 km), Liverpool John Lennon Airport at 41 miles (66 km), Leeds Bradford Airport at 24 miles (39 km), and Blackpool Airport at 33 miles (53 km).

Since 2009, the Reedley Marina has provided a 100-berth facility, on the Leeds and Liverpool Canal on the northern edge of town.[103]

Sport

editThe town's sporting scene is dominated by Burnley Football Club, nicknamed "The Clarets" and founded in 1882.[104] They were one of the first to become professional (in 1883), and subsequently put pressure on the Football Association to permit payments to players.[105] In 1888, Burnley were one of the 12 founder members of the Football League.[104] From the 1950s until the 1970s, under chairman Bob Lord, the club became renowned for its youth policy and scouting system, and was one of the first to set up a purpose-built training ground (Gawthorpe).[106] The team currently compete in the English Football League Championship, the second tier of English football.[107]

The club has played its home matches at Turf Moor since 1883, with average attendances of 20,000 in the Premier League.[108] The club is well supported in the town,[109] and is one of the best supported sides in English football per capita.[110] Burnley have been champions of England twice, in 1920–21 and 1959–60, have won the FA Cup once, in 1913–14, and have won the FA Charity Shield twice, in 1960 and 1973.[111] When the team won the 1959–60 Football League, the town of Burnley became one of the smallest to have an English first tier champion.[106] It is one of only five English league clubs to have been champions of all four professional league divisions (along with Wolverhampton Wanderers, Preston North End, Sheffield United and Portsmouth).[112]

There are two members of the Lancashire Cricket League in the town. Burnley Cricket Club play their home matches at Turf Moor, their ground being adjacent to the football ground, while Lowerhouse Cricket Club play at Liverpool Road. England Cricketer James Anderson started his career at Burnley Cricket Club and TV weatherman John Kettley used to play for them.

Burnley is also home to Burnley Rugby Club (formerly Calder Vale Rugby Club 1926–2001). They field three senior sides, with teams at most junior age groups, and play at Holden Road, the site of Belvedere and Calder Vale Sports Club.

Rugby League is represented in the town by Burnley and Pendle Lions RLFC. They train and play their home games at Prairie Sports Village. They are in the North West Men's Merit League.

Burnley Tornados is the American Football club in the town.

Burnley held greyhound racing and speedway at Towneley Stadium, that existed from 1927 until 1935.

Burnley has good public sporting facilities for a town of its size. The £29m St Peter's Centre (opened in 2006) offers swimming, squash courts and a fitness suite, while the nearby Spirit of Sport complex includes a large sports hall, and several indoor courts and outdoor synthetic pitches.[113] There is an outdoor athletics track at Barden Lane, where the Burnley Athletic Club meets.[114] For golfers, there are both 9-hole and 18-hole municipal golf courses at Towneley Park, along with an 18-hole pitch and putt course.[115] Burnley Golf Club have a private course, established in 1905 above the town in Habergham Eaves.[116] There are tennis courts at Towneley Park, and at the Burnley Lawn Tennis Club,[117] as well as eleven bowling greens around the town,[118] and a £235,000 skate park at Queens Park, which opened in 2003. There are also basketball,[119] caving[120] and judo[121] clubs in the town. In 2001, the private Crow Wood Leisure Centre was established in countryside on the edge of the town, offering a combination of fitness facilities, racquet and equestrian sports.[122] In 2013 Crow Wood opened its own day Spa, the Woodland Spa, which was named Day Spa of the Year at the Professional Beauty Awards 2014, just one year after opening.[123]

Culture and entertainment

editMuseums and galleries

editOn the outskirts of the town there are galleries in two stately homes, the Burnley council-owned Towneley Hall and Gawthorpe Hall in Padiham, which is owned by Lancashire County Council and managed by the National Trust. There are also two local museums: the Weavers' Triangle Trust operates the Visitor Centre and Museum of Local History in the historic surroundings of the Weavers' Triangle, while the Queen Street Mill Textile Museum is unique as the world's only surviving steam driven cotton weaving shed.

Mid Pennine Arts were instrumental in the Panopticons project and run exhibitions and creative learning projects across the town and wider area.[124]

Parks

editThere are several large parks in the town, including Towneley Park, once the deer park for the 15th century Towneley Hall, and three winners of the Green Flag Award, Queens Park which hosts a summer season of brass band concerts each year, and Thompson Park which has a boating lake and miniature railway.[125] The other parks include Scott Park, Ightenhill Park and Thursby Gardens. A greenway route linking Burnley Central Station along a former mineral line and incorporating the former Bank Hall colliery and reclaimed landfill site at Heasandford extends out of the town towards Worsthorne at Rowley Lake. The lake was constructed in the 1980s as a means to divert the river Brun away from former mine workings that were causing significant pollution of the river.

Activities

editThere is a modern 24-lane ten pin bowling centre on Finsley Gate, operated by 1st Bowl. A 9-screen multiplex cinema opened in 1995 (with 3 3D screens as of 2010), operated by Reel Cinemas. The town's theatre, named after its former use as a Mechanics Institute,[126] hosts touring comedians and musical acts and amateur dramatics. In 2005, Burnley Youth Theatre moved into a second, purpose-built £1.5 million performance space next to Queen's Park, one of only two purpose-built youth theatres in the UK.[127]

Festivals

editEach year Burnley hosts the two-day Burnley International Rock and Blues Festival, which started as the Burnley National Blues Festival in 1988.[128] The renamed festival moved from Easter to the early May Bank Holiday. The festival introduced a new logo, website and branding in a bid to attract new and younger audiences, and to encourage cross-town participation with a 'Little America' theme. It is one of the largest blues festivals in the country, drawing fans from all over Britain and beyond to venues spread across the town. In the 1970s, the town was also an important venue for Northern soul[129] and several local pubs still hold regular Northern soul nights. In recent years the town has also hosted the annual Burnley Balloon Festival in Towneley Park and a science festival at UCLan's local university campus. A funfair is usually held around the second weekend in July at Fulledge Recreation Ground, which is also the venue for the town's main Guy Fawkes Night celebration.

In July 2023, the town celebrated its first ever Pride parade.[130] Local charities, organisations, youth groups and trade unions were in attendance at the parade which was led by RuPaul’s Drag Race UK contestant, Elektra Fence.

Nightlife

editMajor bars and nightclubs in Burnley included Lava & Ignite, which was a leading nightclub, which closed in 2014.[131] Curzon Street in Burnley was also the site of the legendary Angels nightclub.

Burnley has a small gay scene, centred on the Guys as Dolls showbar in St James Street.[132] In 1971 the granting of a licence to the town's first gay club, The Esquire, caused considerable controversy, with Tory deputy council leader, Alderman Frank Bailey, suggesting that the building be bought by the corporation to stop the plan.[133] A rainbow plaque was unveiled at Burnley Library on 30 July 2021 marking the 50th anniversary of a meeting organised by the Campaign for Homosexual Equality regarding the gay club.[134]

Bénédictine and hot water, known locally as "Bene 'n' Hot" is a popular drink in east Lancashire, after soldiers stationed in Normandy during the First World War brought back a taste for it. The Burnley Miners' Club is the world's largest consumer of the French liqueur, and has its own Bénédictine Lounge.[135][136][137][138]

Media

editLocal radio for Burnley and its surrounding area is currently provided by Capital Manchester and Lancashire (formerly 2BR) and BBC Radio Lancashire.

Local television news programmes are BBC North West Tonight and ITV Granada Reports.

There are two local newspapers: the Burnley Express, published on Tuesdays and Fridays, and the daily Lancashire Telegraph, which publishes a local edition for Burnley and Pendle. Two free advertisement-supported newspapers, The Citizen[139] and The Reporter, are posted to homes throughout the town.

Burnley was one of seven sites chosen to be part of Channel 4's The Big Art project in which a group of 15 young people from all over the town commissioned artist Greyworld to create a piece of public art. The artwork, named "Invisible", is a series of UV paintings placed all around the town centre displaying public heroes.

Appearance in television and cinema

editParts of the 1961 British film Whistle Down the Wind, and the two BBC television series All Quiet on the Preston Front and Juliet Bravo, were filmed in the town. Burnley Fire Station was the location of Social Services in the first series of Juliet Bravo, and Burnley Library was used for exterior shots of the magistrates' court in the series. Numerous locations in the town were used in the 1996–1998 BBC comedy drama Hetty Wainthropp Investigates. Ashfield Road, which runs between the Burnley College and DIY superstore, was used as a film location in the 1951 film The Man in the White Suit.[140]

Queen Street Mill textile museum was used for a scene in the 2010 Oscar-winning film The King's Speech,[141] and for scenes in the 2004 BBC dramatisation of Elizabeth Gaskell's North and South, as well as Life on Mars (S1 E3; 2006). It has also featured in the following BBC documentaries: Fred Dibnah's Industrial Age (E2; 1999), Adam Hart-Davies' What the Victorians Did for Us (E1; 2001), and Jeremy Paxman's The Victorians (2009), as well as Who Do You Think You Are? (Bill Oddie episode), Flog It and UKTV History's The Re-Inventors (2006).

Towneley Hall featured in the BBC comedy drama Casanova (2005) and the BBC antiques quiz Antiques Master is currently filmed there.[142]

The canal embankment featured in the 2007 ITV documentary Locks and Quays (S2 E9) and two families in Burnley have been featured in the ITV series 60 Minute Makeover (S6 E28 and S7 E70).

In 2023, Netflix released the comedy film "Bank of Dave", billed as a true-ish story of Burnley businessman David Fishwick, who in 2011 opened Burnley Savings & Loans, trading under the slogan 'Bank of Dave'.

Education

editBurnley Grammar School was first established in St Peter's Church in 1559, with its first headmaster a former chantry priest, Gilbert Fairbank. In 1602, one of the governors, John Towneley, paid for a new schoolhouse to be built in the churchyard;[143] the school moved again in 1876 to a new building on Bank Parade, which can still be seen today.[144] The first technical school, in Elizabeth Street, was erected in 1892. The equivalent school for girls, Burnley Girls' High School, was established in 1909 on a site in Ormerod Road (along with the Technical School and Art School)[144] later moving to Kiddrow Lane in the 1960s. The tripartite system of Education established by the Education Act 1944 affected Burnley in the following ways: Heasandford Technical High School for Girls and Towneley Technical High School for Boys were established (Burnley Technical High School was formed in 1956 by the merger of the two),[145] as were Barden, Burnley Wood, Rosegrove & St. Mary's (Roman Catholic) Secondary Modern Schools.

The borough completed the move to comprehensive education in 1981.[146]

Secondary Schools: Habergham (mixed), Ivy Bank (mixed), Gawthorpe (mixed), Towneley (mixed), Barden (boys), Walshaw (girls), St Theodores RC (boys), St Hilda's RC (Girls).

Further education: Habergham and St Theodores Sixth Forms and Burnley College (all mixed).

In 2003 a plan was devised to replace all the secondary schools in the town as part of the first wave of a nationwide programme funded by the Department for Education and Skills called Building Schools for the Future. Funding was secured in 2004[147] and in 2006 the new schools opened (in the buildings of their predecessors).

Today there are still five 11–16 secondary schools:

| School | Locality | Description | Ofsted | Website |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Blessed Trinity RC Community College | Burnley | Secondary school | 134997 | website |

| Burnley High School | Burnley | Secondary school | 141028 | website |

| Sir John Thursby Community College | Burnley | Secondary school | 134996 | website |

| Shuttleworth College | Padiham | Secondary school | 134994 | website |

| Unity College | Burnley | Secondary school | 135003 | website |

Shuttleworth College moved into new buildings in 2008, Sir John Thursby in 2009, and Blessed Trinity, Hameldon and Unity in 2010.

Thomas Whitham Sixth Form, which forms a sixth element of the BSF programme, offers sixth form provision at its Burnley campus (opened 2008) on Barden Lane.

University Technical College Lancashire is a university technical college for 14- to 19-year-olds that opened in Burnley in September 2013. Burnley High School is a free school for 11- to 19-year-olds that opened in Burnley in September 2014.

Burnley College has its heritage in the mid 19th century and is the borough's main tertiary education (post 16) provider, offering a comprehensive range of 40 A Levels, a range of advanced vocational courses and professional training. Apprenticeship courses provided over 1000 local apprenticeship places in 2013, within businesses across Pennine Lancashire. Burnley College in partnership with the University of Central Lancashire (UCLan Burnley) also provides adult education and 70 degree courses.

Burnley College moved to a new £80 million campus, (in partnership with the University of Central Lancashire), off Princess Way in 2009. It achieved 'outstanding' status in that year's OFSTED inspection.[148] The inspection awarded the College 54 out of 54 areas grade one status.

The Mohiuddin Trust charity subsequently purchased the former College site for £2m, and opened the Mohiuddin International Girls' College in October 2010.[149]

Attainment

editThe town's educational attainment has continued to improve over the last few years. In 2012, 82% of children at the end of Key Stage 2 achieved Level 4 or above in English and 81% in Mathematics.[150]

In 2012 59% of students at the end of Key Stage 4 achieved A*-C grades or above at GCSE[151] and in 2012 Burnley College reported a 99.8% A Level pass rate and a record number of A and A* grades.[152][153]

People

editArt

editKeith Coventry, the winner of the 2010 John Moores Painting Prize, was born and educated in the town. The watercolourist Noel Leaver studied and also taught at the former Burnley School of Art, later attended by Greta Tomlinson.

Entertainment

editPossibly the best-known Burnley figure in the field of entertainment is actor Ian McKellen, who was born in the town in 1939. There is a blue plaque on the house where he lived, but where he says he was not born.[154] Other actors born in the town include J. Pat O'Malley, Mary Mackenzie, Irene Sutcliffe, Julia Haworth, Richard Moore,[155][156] Jody Latham, Kathy Jamieson, Hannah Hobley, Natalie Gumede and Lee Ingleby. Coronation Street regular Malcolm Hebden grew up in the town. Screenwriter Paul Abbott, creator of Shameless, and television producer and executive Peter Salmon were also born here.[157]

Musicians born in the town include Danbert Nobacon, Alice Nutter, Lou Watts and Boff Whalley (all of Chumbawamba),[158] Eric Haydock (bassist in The Hollies), classical composer John Pickard,[159] the DJ Anne Savage, Record Producer Ady Hall of Sugar House, young soprano Hollie Steel.[160] and singer Cody Frost.[161]

The 19th-century author and clergyman Silas K. Hocking[162] wrote his most famous work, Her Benny (1879), while living in Burnley. Crime writer Stephen Booth is another native of the town,[163] as are journalist and broadcaster Tony Livesey and author and documentary maker Stewart Binns.

Politics and the church

editDavid Waddington, Lord Waddington of Read (former Conservative Home Secretary and former Lord Privy Seal and Leader of the House of Lords), Phil Willis, Liberal Democrat MP for Harrogate & Knaresborough,[164] and the diplomat Sir Vincent Fean were born in Burnley, as was the 16th-century Catholic martyr Robert Nutter,[165] and the 17th-century Catholic martyr Thomas Whittaker.[166] Suffragettes Margaret Aldersley was born in Burnley in 1852 while Ada Nield Chew died in the town in 1945.

Sir John Stuttard, Lord Mayor of London from 2006 to 2007, was born in Burnley in 1945.

Military

editJames Yorke Scarlett, commander of the Heavy Brigade at the Battle of Balaclava, was married to a Hargreaves coal heiress and lived at Bank Hall. Victoria Cross winners 2nd Lieutenant Hugh Colvin and Private Thomas Whitham both served during World War I.

Science and industry

editEngineer Sir Willis Jackson[167] was born and educated in the town. James Drake, a pioneer of British motorways, was also born here. 17th-century mathematician Sir Jonas Moore was from Higham but is believed to have been educated at the Grammar School. Moore's contemporary, Richard Towneley, pioneered many scientific and technological developments at Towneley Hall. Scottish cardiology pioneer Sir James Mackenzie lived and practised medicine in the town for more than a quarter of a century. The Lasker Award-winning molecular biologist Edwin Southern, inventor of the Southern blot, was born and raised in Burnley.[168]

Sport

editBurnley's sporting figures include England and Lancashire cricketer James Anderson,[169] former England international footballers Jimmy Crabtree,[170] Billy Bannister,[171] and Jay Rodriguez, Northern Ireland international Oliver Norwood,[172] Pakistan international Adnan Ahmed, former England Women's goalkeeper Rachel Brown,[173] ex-Manchester United player Chris Casper,[174] Commonwealth Games Gold Medal-winning gymnast Craig Heap.[175] Supercars Championship driver Fabian Coulthard, second cousin of Formula One driver David Coulthard, was born in Burnley along with Neil Hodgson, 2003 World Superbike champion. Also long-time Burnley F.C. chairman Bob Lord, football pioneer Jimmy Hogan (who grew up in the town), football manager Harry Bradshaw,[176] handball player Holly Lam-Moores,[177] middleweight boxer Jock McAvoy, World Rally Championship navigator Daniel Barritt,[178] and hammer thrower Sophie Hitchon.

See also

edit- Pendelfin, a Burnley-based stoneware company named after Pendle Hill

- Collieries in the Burnley area of Lancashire

- List of mining disasters in Lancashire

References

editFootnotes

- ^ a b Table KS01 Usual resident population, Office for National Statistics, archived from the original on 23 July 2004, retrieved 9 August 2014

- ^ "Burnley – local data profile" (PDF). gov.uk. March 2024. Retrieved 4 August 2024.

- ^ "Burnley named most enterprising place in Britain". Gov.uk. Retrieved 11 June 2022.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Hall 1977, p. 40.

- ^ A History of the county of Lancaster vol 6: Burnley Township @ UK History Accessed 2010

- ^ Historic England. "Two Romano-British farmsteads known as Ring Stones (1009488)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 1 September 2012.

- ^ Historic England. "Twist Castle Romano-British farmstead (1009497)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 1 September 2012.

- ^ Historic England. "Beadle Hill Romano-British farmstead (1009487)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 1 September 2012.

- ^ Lowe, John (1985). Burnley. Phillimore. p. 158. ISBN 978-0-85033-595-8.

- ^ a b c d e f "Our Centres of Industry - 1. Burnley". Lancashire Faces & Places. 1 (1): 10–14. January 1901.

- ^ "Parliamentary accounts and papers". UK Parliament. 23 July 1847. Retrieved 9 December 2015.

- ^ https://www.lancashiretelegraph.co.uk/news/5803798.banks-financial-crash-caused-misery-town/

- ^ Burnley Express Accessed 2010

- ^ Science Museum Archived 20 May 2010 at the Wayback Machine Accessed 2010

- ^ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 25 February 2021. Retrieved 10 September 2020.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ Burnley Borough Council Archived 28 September 2007 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved 6 September 2007.

- ^ Weavers triangle Accessed 2010

- ^ Burnley Express Archived 17 June 2010 at the Wayback Machine Accessed 2010

- ^ "The Story of the Cotton Industry". Spinning The Web. Archived from the original on 24 December 2012. Retrieved 13 June 2010.

- ^ a b "Burnley Lancashire through time | Population Statistics | Total Population". Archived from the original on 1 October 2007. Retrieved 5 October 2006.

- ^ Marsh, Arthur; Ryan, Victoria; Smethurst, John B. (1994). Historical Directory of Trade Unions. Vol. 4. Farnham: Ashgate. pp. 102–103. ISBN 9780859679008.

- ^ "5th Battalion, East Lancashire Regiment". Regiments.org. 15 July 2000. Archived from the original on 28 November 2007. Retrieved 6 October 2009.

- ^ Listed Buildings in Burnley, Britishlistedbuildings.co.uk, Retrieved 3 September 2012

- ^ Otter, Denis (2 December 2004). "World's largest internet honour for war victims". Lancashire Telegraph. Archived from the original on 3 January 2008. Retrieved 25 February 2022.

- ^ Rex. v. Burnley Justices ex parte Longmore (1916) 32 T. L. R. p. 698, referenced in R v Greater London Council, ex parte Blackburn, judgment dated 14 April 1976, accessed 29 May 2024

- ^ Historic England. "Thompson Park (1001496)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 20 July 2021.

- ^ Historic England. "Starfish Bombing Decoy Sf35e (1360177)". Research records (formerly PastScape). Retrieved 20 July 2021.

- ^ "Blitzed! When Hitler's bombs brought death and terror". Lancashire Telegraph. 18 August 1997. Retrieved 20 July 2021.

- ^ "RAF and Commonwealth Air Forces AIR81". RAFCommands. Retrieved 19 July 2021.

- ^ Historic England. "42-50668 (1436774)". Research records (formerly PastScape). Retrieved 20 July 2021.

- ^ magnesium.com Archived 25 June 2017 at the Wayback Machine Accessed 2010

- ^ "Royal Tour Of Lancashire 1955". British Pathé.

- ^ "Bank Hall park – picture and location map". Geograph.org.uk. Retrieved 5 August 2011.

- ^ Marks, Kathy (22 July 1992). "'Copy-cats' blamed for fresh rioting". The Independent. Retrieved 28 January 2019.

- ^ Visit Burnley Accessed 2010

- ^ Lancashire Wildlife Trust Archived 5 December 2008 at the Wayback Machine Accessed 2010

- ^ Burnley Task Force report. Retrieved 6 September 2007

- ^ Burnley Borough Council Archived 14 October 2007 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved 18 September 2007.

- ^ "The Mayor of Burnley 2020/21 | Burnley Borough Council". Archived from the original on 20 October 2020. Retrieved 3 November 2020.

- ^ Burnley Borough Council Archived 27 October 2007 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved 6 November 2007.

- ^ "County Councillors Areas (A-Z)". Archived from the original on 5 May 2010. Retrieved 6 November 2007.

- ^ "Burnley turns blue as Conservatives win seat after more than a century". Lancashire Telegraph. 13 December 2019. Retrieved 20 January 2020.

- ^ Met Office Weather Radar Accessed 2010

- ^ "Welcome to Francesco's!". Panopticons.uk.net. Retrieved 11 June 2022.

- ^ a b UK Census (2011). "Local Area Report – Burnley Local Authority (1946157091)". Nomis. Office for National Statistics. Retrieved 9 February 2018.

- ^ UK Census (2011). "Local Area Report – North West Region (2013265922)". Nomis. Office for National Statistics. Retrieved 9 February 2018.

- ^ UK Census (2011). "Local Area Report – England Country (2092957699)". Nomis. Office for National Statistics. Retrieved 9 February 2018.

- ^ Office for National Statistics. 2001 census. Archived 26 July 2015 at the Wayback Machine Accessed 6 September 2007.

- ^ UK Census (2011). "Local Area Report – Burnley Built-up area (E34004743)". Nomis. Office for National Statistics. Retrieved 6 March 2021.

- ^ a b "Labour Market Profile - Nomis - Official Labour Market Statistics". Nomisweb.co.uk. Retrieved 11 June 2022.

- ^ "Burnley named as burglary capital of England". Lancashire Telegraph. 5 February 2010. Retrieved 5 August 2011.

- ^ ITV1 (15 April 2010). "1st leaders debate video". YouTube. Archived from the original on 13 November 2021. Retrieved 5 August 2011.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ "2008 Affordable Street Rankings" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 30 September 2011. Retrieved 5 August 2011.

- ^ "2009 Affordable Street Rankings" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 14 July 2014. Retrieved 27 February 2013.

- ^ "2010 Affordable Street Rankings" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 14 July 2014. Retrieved 27 February 2013.

- ^ "2011 Affordable Street Rankings" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 14 July 2014. Retrieved 27 February 2013.

- ^ "Burnley CB/MB through time | Population Statistics | Total Population". Archived from the original on 10 August 2014. Retrieved 9 August 2014.

- ^ "Burnley named most enterprising place in Britain". Department for Business, Innovation and Skills. 27 August 2013. Retrieved 7 April 2014.

- ^ Adams, Chris (5 September 2013). "David Cameron heaps praise on Burnley Bondholders scheme". Lancashire Telegraph.

- ^ "Prince Charles joins congratulations for Burnley being named Britain's Most Enterprising Area". Burnley Borough Council. Archived from the original on 1 November 2013.

- ^ "Todmorden Curve £8.8m reinstatement approved". BBC News. 31 October 2011.

- ^ Magill, Peter. "First tenants for Burnley's £1.4million aerospace hub unveiled". Lancashire Telegraph.

- ^ "Barnfield & Burnley Developments Ltd". On the Banks. Archived from the original on 2 November 2013.

- ^ "Vince Cable: Burnley's manufacturing 'booming'". Burnley Borough Council. Archived from the original on 11 August 2014. Retrieved 8 August 2014.

- ^ "Vince Cable opens new £50m business park". Burnley Borough Council. Archived from the original on 11 August 2014. Retrieved 8 August 2014.

- ^ "NOSTALGIA: The last day of coal at Hapton Valley Colliery, Burnley in 1982". Lancashire Telegraph. 7 September 2017. Retrieved 25 February 2022.

- ^ "Prestige: some jobs are saved". Lancashire Telegraph. 5 July 1997. Archived from the original on 3 January 2008. Retrieved 25 February 2022.

- ^ "End of an era". Lancashire Telegraph. 30 December 2002. Archived from the original on 3 January 2008. Retrieved 25 February 2022.

- ^ Institute for Public Policy Research Archived 28 September 2007 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved 6 September 2007.

- ^ "Check Browser Settings". Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 26 January 2008.

- ^ Ten of top 12 most declining UK cities are in north of England – report, The Guardian, 29 February 2016, accessed 12 February 2017

- ^ "Statistics | Burnley Borough Council". Archived from the original on 8 August 2014. Retrieved 8 August 2014.

- ^ "Shop Direct call centre closes in Burnley". BBC News. 30 June 2010. Retrieved 5 August 2011.

- ^ Burnley Council Archived 15 June 2011 at the Wayback Machine Accessed 2010

- ^ This is Lancashire Accessed 2010

- ^ Central Lancashire City Region Development Programme Archived 29 July 2007 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved 11 September 2007.

- ^ Magill, Peter (12 April 2011). "120 jobs to go as Burnley aero site closes". Lancashire Telegraph. Retrieved 25 February 2022.

- ^ "Lancashire Digital Technology Centre". Archived from the original on 25 August 2007. Retrieved 1 September 2007.

- ^ "Innovation Drive". Burnley. Archived from the original on 11 August 2014.

- ^ "Ian Mankin | British Weavers of Designer Fabrics". Archived from the original on 7 March 2022. Retrieved 7 March 2022.

- ^ "The Most Beautiful Landmark Trust Holiday Homes | Ian Mankin". Archived from the original on 7 March 2022. Retrieved 7 March 2022.

- ^ YMCA Archived 18 July 2009 at the Portuguese Web Archive Accessed 2010

- ^ Financial Times Accessed 2010

- ^ "Visit Burnley". Retrieved 2 January 2018.

- ^ "20 More stores for our town". Burnley Express. 30 July 2004. Archived from the original on 3 August 2012. Retrieved 14 January 2012.

- ^ "Burnley new shopping centre moves step closer". Burnley Express. 3 February 2011. Archived from the original on 3 August 2012. Retrieved 14 January 2012.

- ^ "New cinema and restaurants coming to Burnley". Burnley. Archived from the original on 11 August 2014.

- ^ "£3m Green light for Burnley centre". Burnley. Archived from the original on 11 August 2014.

- ^ Michael Whittaker. "Worsthorne Brewing Company". Archived from the original on 23 April 2012.

- ^ "HOME - ministryofale.co.uk". Archived from the original on 24 April 2020. Retrieved 1 September 2012.

- ^ Burnley, GenUKI, retrieved 1 September 2012

- ^ "Towneley Chapel, Burnley – Roman Catholic", Burnley, GENUKI, retrieved 2 September 2012

- ^ Mosques in Burnley, Lancashire, Mosques.muslimsinbriutain.org, Retrieved 5 September 2012

- ^ New £1.5million mosque opens in Burnley, The Burnley Citizen, 14 October 2009, retrieved 1 September 2012

- ^ Listed Buildings in Burnley, Britishlistedbuildings.co.uk, Retrieved 18 September 2012

- ^ "Burnley Embankment - The Straight Mile". 12 September 2007. Archived from the original on 12 September 2007. Retrieved 11 June 2022.

- ^ Towneley Hall Official Site Archived 8 May 2008 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved 24 September 2008.

- ^ "'Most dangerous' roads revealed". News.bbc.co.uk. 24 June 2007. Retrieved 11 June 2022.

- ^ "Work begins on project to reinstate major rail link". Todmordennews.co.uk. Archived from the original on 25 July 2015. Retrieved 11 June 2022.

- ^ "Groundbreaking Ceremony – New £2.3 million Burnley Manchester Road Station | Burnley Borough Council". burnley.gov.uk. Archived from the original on 5 March 2016. Retrieved 17 January 2022.

- ^ "Strzala Architects". sbsarch.co.uk. Retrieved 2 January 2018.

- ^ "UK Bus Awards :: 2003 Infrastructure". 11 September 2007. Archived from the original on 11 September 2007. Retrieved 11 June 2022.

- ^ "Reedley Marina". Archived from the original on 28 June 2010. Retrieved 2 January 2018.

- ^ a b Moor, Dave. "Burnley". Historical Football Kits. Retrieved 24 January 2018.

- ^ Simpson, Ray (2007). The Clarets Chronicles: The Definitive History of Burnley Football Club 1882–2007. Burnley F.C. pp. 20–24. ISBN 978-0955746802.

- ^ a b Quelch, Tim (2015). Never Had It So Good: Burnley's Incredible 1959/60 League Title Triumph. Pitch Publishing Ltd. pp. 199–206. ISBN 978-1909626546.

- ^ Rundle, Richard. "Burnley". Football Club History Database. Retrieved 8 May 2020.

- ^ "Burnley Performance Stats". ESPN. Retrieved 13 February 2021. Individual seasons accessed via dropdown menu.

- ^ "Burnley look for revival". Stuff. 31 January 2009. Archived from the original on 10 October 2020. Retrieved 10 May 2020.

- ^ Johnson, William (27 December 2001). "Burnley's head for heights". The Telegraph. Archived from the original on 22 December 2020. Retrieved 25 December 2019.

- ^ "Burnley football club honours". 11v11. AFS Enterprises. Retrieved 26 January 2018.

- ^ Tyler, Martin (9 May 2017). "Martin Tyler's stats: Most own goals, fewest different scorers in a season". Sky Sports. Archived from the original on 14 April 2020. Retrieved 15 August 2018.

- ^ Burnley Borough Council Archived 28 September 2007 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved 7 September 2007.

- ^ "Burnley Athletic Club". Archived from the original on 19 April 2013. Retrieved 2 January 2018.

- ^ www.burnley.gov.uk Archived 15 June 2011 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved 4 December 2007

- ^ "BURNLEY GOLF CLUB". Burnleygolfclub.com. Retrieved 2 January 2018.

- ^ "Burnley Lawn Tennis Club". Clubspark.lat.org.uk. Retrieved 11 June 2022.

- ^ Burnley Borough Council Archived 28 September 2007 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved 7 September 2007.

- ^ "Burnley Basketball Club". Archived from the original on 20 July 2011.

- ^ "Burnley Caving Club : Our Club". Burnleycavingclub.org.uk. Retrieved 2 January 2018.

- ^ "Burnley Judo Club". Archived from the original on 15 March 2012.

- ^ "Crow Wood - a unique concept in health, fitness and leisure in Burnley". Crow Wood. Retrieved 11 June 2022.

- ^ "Woodland Spa. Best in Britain!". Burnley. Archived from the original on 11 August 2014.

- ^ "Mid Pennine Arts". Midpenniearts.org.uk. Retrieved 11 June 2022.

- ^ "Green Flag Award - The National Standard for Parks and Green Spaces". 30 April 2005. Archived from the original on 30 April 2005. Retrieved 11 June 2022.

- ^ "Burnley Mechanics". Archived from the original on 25 September 2006. Retrieved 17 September 2006.

- ^ "drama burnley drama and dance workshops for children and young people". Burnley Youth Theatre. Retrieved 11 June 2022.

- ^ "Burnley Blues Festival". Archived from the original on 28 September 2006.

- ^ Roberts, Northern Soul Top 500, p.369

- ^ "Burnley Pride". Discover Burnley Town Centre. Retrieved 19 November 2023.

- ^ "Burnley's Lava & Ignite nightclub closes". Pendle Today. Archived from the original on 16 March 2016. Retrieved 7 April 2014.

- ^ FLAG Burnley Archived 15 December 2008 at the Wayback Machine Accessed 2010

- ^ "Esquire Clubs – The Burnley Meeting at gaymonitor.co.uk". Archived from the original on 22 December 2011.

- ^ Jacobs, Bill (29 July 2021). "Landmark Burnley gay meeting to be commemorated". Lancashire Telegraph. Retrieved 1 August 2023.

- ^ Smith, Richard (18 May 1994), "Liqueur is hot stuff at working men's club", The Independent, London, retrieved 3 September 2012

- ^ "It's a Bene for the guy, folks!", Lancashire Telegraph, 1 November 2004, retrieved 3 September 2012

- ^ "Limited edition Bene for club", Burnley Express, 3 November 2010, archived from the original on 1 April 2016, retrieved 3 September 2012

- ^ "The Tommies' tipple is back in vogue", Manchester Evening News, 2 August 2002, archived from the original on 3 July 2007, retrieved 23 October 2007

- ^ "Burnley & Pendle Citizen". Burnley & Pendle Citizen. Retrieved 7 April 2014.

- ^ "British filming location from Man In The White Suit, The (1951) – Sid's lodgings". British Firm Locations. Retrieved 21 March 2015.

- ^ Burnley Express Archived 1 October 2011 at the Wayback Machine Accessed 2011

- ^ BBC Programmes Accessed 2010

- ^ Hall & Spencer, Burnley: A Pictorial History, p. 2

- ^ a b "Explore Burnley". Burnley.co.uk. Retrieved 11 June 2022.

- ^ BTHS Index Archived 26 April 2012 at the Wayback Machine Accessed 2010

- ^ at which point the town had the following schools:Burnley St Peter's Heritage – Story of Church and Town Archived 3 March 2021 at the Wayback Machine. Burnleystpeterheritage.co.uk, Retrieved 13 November 2007

- ^ "Concerns over plans for £170m overhaul". Lancashire Telegraph. 9 August 2004. Retrieved 25 February 2022.

- ^ "Find an inspection report and registered childcare". Reports.ofsted.gov.uk. 8 October 2020. Retrieved 11 June 2022.

- ^ Burnley Express Archived 14 September 2010 at the Wayback Machine Accessed 2010

- ^ "The Department for Education - Performance Tables - Search results". Archived from the original on 25 July 2015. Retrieved 2 June 2013.

- ^ "The Department for Education - Performance Tables - Search results". Archived from the original on 14 July 2014. Retrieved 2 June 2013.

- ^ "99.8% A Level pass rate, a record number of a and A* grades and over three quarters achieving top grades". Archived from the original on 13 May 2013. Retrieved 2 June 2013. Accessed 2013

- ^ "British towns twinned with French towns [via WaybackMachine.com]". Archant Community Media Ltd. Archived from the original on 5 July 2013. Retrieved 20 July 2013.

- ^ "Sir Ian plaque 'outside wrong house'". The Bolton News. 2 January 2007.

- ^ "Emmy star reveals it's Clarets life for him". Lancashire Telegraph. 20 July 2005. Archived from the original on 3 January 2008. Retrieved 25 February 2022.

- ^ Urban Talent Acting Agency Archived 2 April 2009 at the Wayback Machine. Accessed 22 October 2007.

- ^ Brown, Maggie (11 December 2006). "Interview with BBC chief creative officer Peter Salmon". The Guardian. Retrieved 25 February 2022.

- ^ A Chumbawamba FAQ. Accessed 22 October 2007.

- ^ Rickards, 'Icarus Soaring: The Music of John Pickard', p.2

- ^ "Britain's Got Talent star Hollie supported all the way by her big brother". Lancashire Telegraph. 3 May 2009. Retrieved 25 February 2022.

- ^ "Glastonbury debut for talented Burnley singer was an 'absolute dream'". Burnley Express. 1 July 2022. Retrieved 22 December 2022.

- ^ Burnley Borough Council Archived 28 September 2007 at the Wayback Machine. Accessed 23 October 2007.

- ^ "Stephen Booth - biography". Stephen-booth.com. Retrieved 11 June 2022.

- ^ Liberal Democrats official site Archived 7 November 2007 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved 23 October 2007.

- ^ "CATHOLIC ENCYCLOPEDIA: Robert Nutter and Edward Thwing". Newadvent.org. Retrieved 11 June 2022.

- ^ "Burnley KSC plaque commemorates Catholic martyrs". Burnley Express. 18 July 2017. Retrieved 14 July 2023.

- ^ "AIM25: Imperial College of Science, Technology and Medicine: JACKSON, Willis, Baron Jackson of Burnley (1904-1970)". Archived from the original on 26 September 2006. Retrieved 23 October 2007.

- ^ Harding, Anne (3 December 2005). "Sir Edwin Southern: scientist as problem solver". Perspectives. 366 (9501): 1919. PMID 16325686.