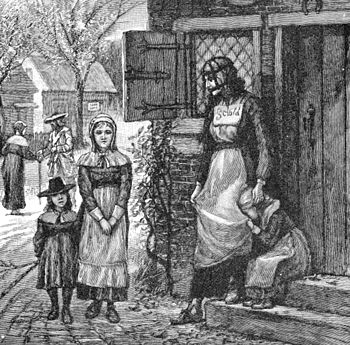

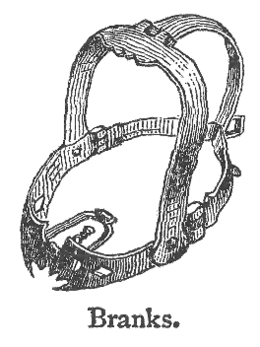

A scold's bridle, sometimes called a witch's bridle, a gossip's bridle, a brank's bridle, or simply branks,[1] was an instrument of punishment, as a form of public humiliation.[2] It was an iron muzzle in an iron framework that enclosed the head (although some bridles were masks that depicted suffering). A bridle-bit (or curb-plate), about 5 cm × 2.5 cm (2 in × 1 in) in size, was slid into the mouth and pressed down on top of the tongue, often with a spike on the tongue, as a compress. It functioned to silence the wearer from speaking entirely, to prevent the women from nagging. The scold's bridle was used on women.[3] This prevented speaking and resulted in many unpleasant side effects for the wearer, including excessive salivation and fatigue in the mouth. For extra humiliation, a bell could also be attached to draw in crowds. The wearer was then led around town by a leash.[citation needed]

Origin and purpose

editEngland and Scotland

editFirst recorded in Scotland in 1567, the branks were also used in England and its colonies. The kirk-sessions and barony courts in Scotland inflicted the contraption mostly on female transgressors and women considered to be rude, nags, common scolds, or drunken.[3][4]

Branking (in Scotland and the North of England)[5][6][7][1] was designed as a mirror punishment for shrews or scolds—women of the lower classes whose speech was deemed riotous or troublesome[8]—by preventing them from speaking. This also gives it its other name, the Gossip's Bridle.

It was also used as corporal punishment for other offences, notably on female workhouse inmates. The person to be punished was placed in a public place for additional humiliation and sometimes beaten.[9] The Lanark Burgh Records record a typical example of the punishment being used: "Iff evir the said Elizabeth salbe fund [shall be found] scolding or railling ... scho salbe sett [she shall be set] upone the trone in the brankis and be banishit [banished of] the toun thaireftir [thereafter]" (1653 Lanark B. Rec. 151).

When the branks was installed, the wearer could be led through town to show that they had committed an offence or scolded too often. This was intended to humiliate them into repenting their alleged offensive actions. A spike inside the gag prevented any talking since any movement of the mouth could cause a severe piercing of the tongue.[5] When wearing the device, it was impossible for the person either to eat or speak.[10] Other branks included an adjustable gag with a sharp edge, causing any movement of the mouth to result in laceration of the tongue.

In Scotland, branks could also be permanently displayed in public by attaching them, for example, to the town cross, tron, or tolbooth. Then, the ritual humiliation would take place, with the convict on public show. Displaying the branks in public was intended to remind the populace of the consequences of any rash action or slander. Whether the person was paraded or simply taken to the point of punishment, the process of humiliation and expected repentance was the same. Time spent in the bridle was normally allocated by the kirk session, in Scotland, or a local magistrate.[10]

Quaker women were sometimes punished with the branks by non-Quaker authorities for preaching their religious doctrine in public places.[11]

Jougs were similar in their effect to a pillory, but did not restrain the sufferer from speaking. They were generally used in both England and Scotland in the 16th and 17th centuries.[5]

The New World

editThe scold's bridle did not see much use in the New World, though Olaudah Equiano recorded seeing it used to control a Virginia slave in the mid-18th century.

Escrava Anastacia ('Anastacia the female slave') is a Brazilian folk saint said to have died from wearing a punitive slave iron bit.

Historical examples

edit- Scotland

In 1567, Bessie Tailiefeir (pronounced Telfer) allegedly slandered the baillie Thomas Hunter in Edinburgh, saying that he was using false measures. She was sentenced to be "brankit" and fixed to the cross for one hour.[12]

- England

Two bridles were bought for use by the magistrates of Walsall in the 17th century, but it is not clear what happened to them or whether they were ever used.[5] The Quaker preacher Dorothy Waugh was subjected to the bridle in 1655 in Carlisle and wrote an account of her imprisonment.[13]

In Walton-on-Thames, Surrey, a replica of a scold's bridle from 1633 that was stolen in 1965, was in a dedicated cabinet in the vestry of the church, with the inscription "Chester presents Walton with a bridle, to curb women's tongues that talk too idle." Oral tradition is this Chester lost a fortune due to a woman's gossip, and presented the instrument of restraint or torture out of anger and spite.[14][15] The church states it came to the parish in 1723 from Chester.[14] The bridle was donated by the parish to Big Heritage CIC, an organisation based in Chester, for use in their museum displays, as it was felt to be inappropriate to continue to display it in a church building.

Mediæval London (1906) named six instances "of branks preserved, I believe, to this day ... at Worcester, Ludlow, Newcastle-under-Lyme, Oxford, Shrewsbury ... Lichfield ... and many other places".[15]

As late as 1856 such an item was used at Bolton le Moors, Lancashire.[4]

In fiction

edit- The Scold's Bridle is the title of a novel by Minette Walters, where a scold's bridle is a key element in the plot.

- In Brimstone (2016) actress Carice van Houten is wearing a scold's bridle in some scenes.

- In Three Men in a Boat (1889), the iron scold's bridle at Walton Church in Walton on Thames, Surrey, is mentioned as a local item of interest.[16]

See also

editReferences

edit- ^ a b "Dictionary of the Scots Language: SND: branks n1". Dsl.ac.uk. Archived from the original on 2019-03-09. Retrieved 2020-04-04.

- ^ "Definition of branks". Free Dictionary. Archived from the original on 29 April 2019. Retrieved 7 August 2012.

- ^ a b "Scolds Bridle". National Education Network, U.K. Archived from the original on 10 January 2018. Retrieved 7 August 2012.

- ^ a b Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 4 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 430–431.

- ^ a b c d "History talk sheds light on Scold's Bridle". Retrieved 7 August 2012.[permanent dead link]

- ^ Chambers, Robert (1859–1861). Domestic Annals of Scotland. Edinburgh : W & R Chambers. p. 90.

- ^ Domestic annals of Scotland, from the reformation ... v.0001. – Full View. 2010-04-29. Archived from the original on 2021-09-20. Retrieved 2020-04-04.

{{cite book}}:|website=ignored (help) - ^ "Victorian workhouse punishments – the scold's bridle". history.powys.org.uk. Archived from the original on 5 May 2018. Retrieved 27 April 2018.

- ^ "occasional hell – infernal device – Branks". www.occasionalhell.com. Archived from the original on 28 April 2018. Retrieved 27 April 2018.

- ^ a b "Scold's bridle, Germany, 1550–1800". www.sciencemuseum.org.uk. Archived from the original on 12 October 2015. Retrieved 27 April 2018.

- ^ "Quakers". Archived from the original on 30 September 2015. Retrieved 27 April 2018.

- ^ Chambers, Robert (1885). Domestic Annals of Scotland. Edinburgh: W & R Chambers. p. 37.

- ^ Matthew, H. C. G.; Harrison, B., eds. (2004-09-23). "Dorothy Waugh in The Oxford Dictionary of National Biography". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. ref:odnb/69140. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/69140. Retrieved 2023-04-29. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- ^ a b "Tour of St Mary's Church". Walton Parish. Archived from the original on 2020-02-07. Retrieved 2020-04-04.

- ^ a b Besant, Walter (1906). Mediæval London. Vol. 1. Cornell University Library. London: Adam & Charles Black. pp. 356–357.

- ^ Jerome, Jerome K. (1889). Three Men in a Boat *To Say Nothing of the Dog). Bristol: J. W. Arrowsmith. p. 87.

External links

edit- Media related to Scold's bridles at Wikimedia Commons

- Bygone Punishments of Scotland by William Andrews 1899 on electricscotland