Hardingstone is a village in Northamptonshire, England. It is on the southern edge of Northampton, and now forms a suburb of the town. It is about 1 mile (2 km) from the town centre. The Newport Pagnell road (the B526, formerly part of the A50) separates the village from the nearby village of Wootton, which has also been absorbed into the urban area.

| Hardingstone | |

|---|---|

Queen Eleanor's Cross, London Road, Hardingstone, Northampton | |

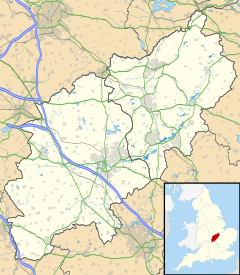

Location within Northamptonshire | |

| Population | 2,014 (2011) |

| OS grid reference | SP765575 |

| Unitary authority | |

| Ceremonial county | |

| Region | |

| Country | England |

| Sovereign state | United Kingdom |

| Post town | Northampton |

| Postcode district | NN4 |

| Dialling code | 01604 |

| Police | Northamptonshire |

| Fire | Northamptonshire |

| Ambulance | East Midlands |

| UK Parliament | |

The parish includes part of the Brackmills Industrial Estate, and borders Delapré Abbey.

History

editHardingstone is first mentioned in Domesday Book.[1]

The parish is rich in archaeological remains, having remants of both the prehistoric and Roman periods.[1]

Etymology

editThe village's name means 'Hearding's Thorn-tree'.[2]

Iron Ore Quarries

editIron ore quarrying began at Hardingstone in about 1852. It is likely that quarrying had ceased by 1860. The quarry was to the east of the old village area and to the north of the Bedford Road. Part of it has had houses built on it and Landimore Road now crosses the site as well as a footpath. Traces of the quarry are visible. The ore was taken away by a tramway leading to the Northampton to Peterborough railway line (now closed.) It is likely that the upper part of the tramway was worked by a stationary steam engine. Part of the route of the tramway has been built over and part (near to the railway) has been dug up by gravel workings or flood prevention works and flooded.[3] There were later workings in the Far Cotton part of the old Hardingstone Parish.

The Blazing car murder

editHardingstone Lane was the scene of the Blazing car murder of 1931 which attracted sensational national interest. The felon, Alfred Rouse, was tried at Northampton Assizes and subsequently hanged in Bedford Gaol on 10 March 1931. The male victim has never been identified and was buried at Hardingstone church.[4] In January 2014, it was revealed that DNA had been found in the Northamptonshire 'blazing car' murder case and the identity of the victim might at last be found.[5][6] However, the family who feared for more than 80 years that their relative was the victim were told by scientists the victim's DNA did not match theirs.[7] In October 2014, scientists trying to identify the murder victim said they were down to nine strong leads.[8] In December 2014, Dr John Bond, forensic science expert at the University of Leicester, said he would look into the possibility of a Mr Brick from Wales being the victim of Rouse.[9]

Administration

editThere are two tiers of local government covering Hardingstone, at parish and unitary authority level: Hardingstone Parish Council and West Northamptonshire Council, based in Northampton. The parish council is based at the Parish Rooms on the High Street.[10]

Administrative history

editHardingstone was an ancient parish.[11] The Northampton parliamentary constituency was extended south of the River Nene in 1868 to include the Cotton End and Far Cotton areas of the parish. In 1871 the parts of the parish within the Northampton constituency were made a local government district called Hardingstone, although the village itself was in the part of the parish outside the local government district.[12]

The Hardingstone district was enlarged in 1874 to take in the ecclesiastical parish of St James, which had been created in 1872 covering the growing western suburbs of Northampton.[13][14]

Local government districts were reconstituted as urban districts under the Local Government Act 1894, which also said that parishes could no longer straddle district boundaries. Hardingstone parish was therefore reduced to cover just the part of the parish outside the urban district, whilst the part inside the urban district became a parish called Far Cotton. The confusion of having a Hardingstone Urban District which did not contain Hardingstone itself did not last long; in 1896 the urban district was divided into two urban districts called Far Cotton and St James,[15] both of which were abolished four years later in 1900 and absorbed into the county borough of Northampton.

The rural parish of Hardingstone was included in the Hardingstone Rural District from 1894 to 1932 and the Northampton Rural District from 1932 to 1974.[11] In 1968 Hardingstone was included within the designated area for the expansion of Northampton as a new town,[16] and six years later in 1974 the parish was absorbed into the borough of Northampton, whilst remaining a civil parish.[17] The borough of Northampton was abolished in 2021 to become part of West Northamptonshire.[18]

Demographics

editThe 2001 census[19] showed there were 2,015 people living in the parish: 978 males and 1,037 females in 885 households. The 2011 census showed a very minor reduction to 2,014.[20]

Geography

editBrackmills

editTo the north-east of the village is the large Brackmills Industrial Estate. The estate was chosen as the site of a 400 ft wind turbine erected by the Asda supermarket chain at one of their warehouses, but this was rejected by the planners.

Facilities

editThe original village school was built around 1860-70 by General Bouverie; this building remained open until the 1972 when the primary school was transferred to a more modern building in Martin's Lane, and the old school was transferred to Northampton County Council (Social Services) who now let it to the Hardingstone Village Hall Association.

The village has two pubs: "The Crown" and "The Sun" along with a post office, corner shop and several hairdressers.

Queen Eleanor's Cross

editOn the edge of the village, on the road going into Northampton, can be found one of only three remaining Eleanor crosses. The cross commemorates the resting at nearby Delapré Abbey of the body of Queen Eleanor of Castile; King Edward I stayed at nearby Northampton Castle. The cross was begun in 1291 by John of Battle; he worked with William of Ireland to carve the statues; William was paid five marks (£3 6s. 8d. or £3.33) per figure.

The cross is octagonal and set on some steps, the present ones being replacements. The cross is built in three tiers and originally had a crowning terminal – possibly a cross. It is not known when this was lost, but it had been lost by the time of the second Battle of Northampton in 1460. Its bottom tier features open books; these probably included painted inscriptions of Eleanor's biography and of prayers for her soul to be said by viewers, which are now lost.

The cross is referred to in Daniel Defoe's A tour thro' the whole island of Great Britain, where he reports on the Great Fire of Northampton in 1675:

... a townsman being at Queen's Cross upon a hill on the south side of the town, about two miles off, saw the fire at one end of the town then newly begun, and that before he could get to the town it was burning at the remotest end, opposite where he first saw it.

Restoration work was completed in 2019.[21]

Whilst the cross was historically part of Hardingstone village, it is now administratively within Far Cotton and Delapre.

Church

editThe parish church of St Edmund dates back to the 12th century and is mentioned in documents from 1107. Nikolaus Pevsner considered that the body of the church had been over-restored. He mentions no features as early as the 12th century but refers to the tower as from the thirteenth century and arcades of the fourteenth century with octagonal piers.[22]

Many members of the Bouverie family (owners of nearby Delapré Abbey) are buried in the vault. The family used this as their family church because the Abbey, after the Dissolution of the Monasteries, lacked its own chapel.

During the Second World War the stained glass windows were removed for safety but afterwards could not be found. Some people[who?] believe that they might be in the Bouverie family vault, but this is bricked up and the mystery remains.[citation needed]

Notable residents

edit- Robert Adams (sculptor and designer)

- Thomas Croxen Archer (1817-1885), botanist, and first Director of the National Museum of Scotland

- James Hervey, (1714-1756) Clegyman and writer was born in Hardingstone.

References

edit- ^ a b "Hardingstone | British History Online". www.british-history.ac.uk. Retrieved 17 June 2024.

- ^ "Key to English Place-names".

- ^ Tonks, Eric (1989). The Ironstone Quarries of the Midlands: Part 3 The Northampton Area. Cheltenham: Runpast. pp. 122–7. ISBN 1-870754-03-4.

- ^ "Northants Police Archive". Archived from the original on 29 May 2008. Retrieved 8 July 2008.

- ^ "DNA found in Northamptonshire 'blazing car' murder case" BBC News 2014_01_14, Accessed 2014_01_14

- ^ "Northamptonshire Police may look at 1930 'blazing car murder'" BBC News 2012_05_03, Accessed 2014_01_14

- ^ BBC News 22 January 2013, Accessed 2014_01_22

- ^ "Northamptonshire 1930 'blazing car murder': Nine families shortlisted" BBC News 18 October 2014, accessed 18 October 2014

- ^ "Alfred Rouse 'blazing car murder': Victim could be missing man" BBC News 20 December 2014

- ^ "Hardingstone Parish Council". Retrieved 7 November 2023.

- ^ a b "Hardingstone Ancient Parish / Civil Parish". A Vision of Britain through Time. GB Historical GIS / University of Portsmouth. Retrieved 7 November 2023.

- ^ "No. 23797". The London Gazette. 17 November 1871. p. 4717.

- ^ "No. 23886". The London Gazette. 13 August 1872. p. 3593.

- ^ "Local Government Board's Provisional Orders Confirmation (No. 4) Act 1874". legislation.gov.uk. The National Archives. Retrieved 7 November 2023.

- ^ Annual Report of the Local Government Board. London: Her Majesty's Stationery Office. 1896. p. 368. Retrieved 7 November 2023.

- ^ "No. 44529". The London Gazette. 20 February 1968. p. 2088.

- ^ "The English Non-metropolitan Districts (Definition) Order 1972", legislation.gov.uk, The National Archives, SI 1972/2039, retrieved 7 November 2023

- ^ "The Northamptonshire (Structural Changes) Order 2020", legislation.gov.uk, The National Archives, SI 2020/156, retrieved 7 November 2023

- ^ "UK census 2001 - data". Retrieved 3 October 2008.

- ^ "Civil Parish population 2011". Neighbourhood Statistics. Office for National Statistics. Retrieved 4 July 2016.

- ^ "Eleanor Cross: Conservation of Northampton monument complete". BBC News. 15 November 2019. Retrieved 16 November 2019.

- ^ Pevsner, Nikolaus (1972). Cherry, Bridget (ed.). Northamptonshire. Buildings of England (2nd ed.). Harmondsworth, Middlesex (London): Penguin. p. 353. ISBN 0-14-0710-22-1.

External links

editMedia related to Hardingstone at Wikimedia Commons

- Pevsner - The Buildings of England - Northamptonshire. ISBN 0-300-09632-1

- Northamptonshire County Council

- Hardingstone Parish Council

- Hardingstone Village Hall