Alice and Bob are fictional characters commonly used as placeholders in discussions about cryptographic systems and protocols,[1] and in other science and engineering literature where there are several participants in a thought experiment. The Alice and Bob characters were invented by Ron Rivest, Adi Shamir, and Leonard Adleman in their 1978 paper "A Method for Obtaining Digital Signatures and Public-key Cryptosystems".[2] Subsequently, they have become common archetypes in many scientific and engineering fields, such as quantum cryptography, game theory and physics.[3] As the use of Alice and Bob became more widespread, additional characters were added, sometimes each with a particular meaning. These characters do not have to refer to people; they refer to generic agents which might be different computers or even different programs running on a single computer.

Overview

editAlice and Bob are the names of fictional characters used for convenience and to aid comprehension. For example, "How can Bob send a private message M to Alice in a public-key cryptosystem?"[2] is believed to be easier to describe and understand than if the hypothetical people were simply named A and B as in "How can B send a private message M to A in a public-key cryptosystem?"

The names are conventional, and where relevant may use an alliterative mnemonic such as "Mallory" for "malicious" to associate the name with the typical role of that person.

History

editScientific papers about thought experiments with several participants often used letters to identify them: A, B, C, etc.

The first mention of Alice and Bob in the context of cryptography was in Rivest, Shamir, and Adleman's 1978 article "A method for obtaining digital signatures and public-key cryptosystems."[2] They wrote, "For our scenarios we suppose that A and B (also known as Alice and Bob) are two users of a public-key cryptosystem".[2]: 121 Previous to this article, cryptographers typically referred to message senders and receivers as A and B, or other simple symbols. In fact, in the two previous articles by Rivest, Shamir, and Adleman, introducing the RSA cryptosystem, there is no mention of Alice and Bob.[4][5] The choice of the first three names may have come from the film Bob & Carol & Ted & Alice.[6]

Within a few years, however, references to Alice and Bob in cryptological literature became a common trope. Cryptographers would often begin their academic papers with reference to Alice and Bob. For instance, Michael Rabin began his 1981 paper, "Bob and Alice each have a secret, SB and SA, respectively, which they want to exchange."[7] Early on, Alice and Bob were starting to appear in other domains, such as in Manuel Blum's 1981 article, "Coin Flipping by Telephone: A Protocol for Solving Impossible Problems," which begins, "Alice and Bob want to flip a coin by telephone."[8]

Although Alice and Bob were invented with no reference to their personality, authors soon began adding colorful descriptions. In 1983, Blum invented a backstory about a troubled relationship between Alice and Bob, writing, "Alice and Bob, recently divorced, mutually distrustful, still do business together. They live on opposite coasts, communicate mainly by telephone, and use their computers to transact business over the telephone."[9] In 1984, John Gordon delivered his famous[10] "After Dinner Speech" about Alice and Bob, which he imagines to be the first "definitive biography of Alice and Bob."[11]

In addition to adding backstories and personalities to Alice and Bob, authors soon added other characters, with their own personalities. The first to be added was Eve, the "eavesdropper." Eve was invented in 1988 by Charles Bennet, Gilles Brassard, and Jean-Marc Robert, in their paper, "Privacy Amplification by Public Discussion."[12] In Bruce Schneier's book Applied Cryptography, other characters are listed.[13]

Cast of characters

editCryptographic systems

editThis section needs additional citations for verification. (May 2023) |

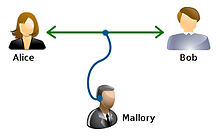

The most common characters are Alice and Bob. Eve, Mallory, and Trent are also common names, and have fairly well-established "personalities" (or functions). The names often use alliterative mnemonics (for example, Eve, "eavesdropper"; Mallory, "malicious") where different players have different motives. Other names are much less common and more flexible in use. Sometimes the genders are alternated: Alice, Bob, Carol, Dave, Eve, etc.[14]

| Alice and Bob | The original, generic characters. Generally, Alice and Bob want to exchange a message or cryptographic key. |

| Carol, Carlos or Charlie | A generic third participant. |

| Chuck or Chad | A third participant, usually of malicious intent.[15] |

| Craig | A password cracker, often encountered in situations with stored passwords. |

| Dan, Dave or David | A generic fourth participant. |

| Erin | A generic fifth participant, but rarely used, as "E" is usually reserved for Eve. |

| Eve or Yves | An eavesdropper, who is usually a passive attacker. While they can listen in on messages between Alice and Bob, they cannot modify them. In quantum cryptography, Eve may also represent the environment.[clarification needed] |

| Faythe | A trusted advisor, courier or intermediary. Faythe is used infrequently, and is associated with faith and faithfulness. Faythe may be a repository of key service or courier of shared secrets.[citation needed] |

| Frank | A generic sixth participant. |

| Grace | A government representative. For example, Grace may try to force Alice or Bob to implement backdoors in their protocols. Grace may also deliberately weaken standards.[16] |

| Heidi | A mischievous designer for cryptographic standards, but rarely used.[17] |

| Ivan | An issuer, mentioned first by Ian Grigg in the context of Ricardian contracts.[18] |

| Judy | A judge who may be called upon to resolve a potential dispute between participants. See Judge Judy. |

| Mallory[19][20][21] or (less commonly) Mallet[22][23][24][25] or Darth[26] | A malicious attacker. Associated with Trudy, an intruder. Unlike the passive Eve, Mallory is an active attacker (often used in man-in-the-middle attacks), who can modify messages, substitute messages, or replay old messages. The difficulty of securing a system against a Mallory is much greater than against an Eve. |

| Michael or Mike | Used as an alternative to the eavesdropper Eve, from microphone. |

| Niaj | Used as an alternative to the eavesdropper Eve in several South Asian nations.[27] |

| Olivia | An oracle, who responds to queries from other participants. Olivia often acts as a "black box" with some concealed state or information, or as a random oracle. |

| Oscar | An opponent, similar to Mallory, but not necessarily malicious. |

| Peggy or Pat | A prover, who interacts with the verifier to show that the intended transaction has actually taken place. Peggy is often found in zero-knowledge proofs. |

| Rupert | A repudiator who appears for interactions that desire non-repudiation. |

| Sybil | A pseudonymous attacker, who usually uses a large number of identities. For example, Sybil may attempt to subvert a reputation system. See Sybil attack. |

| Trent or Ted | A trusted arbitrator, who acts as a neutral third party. |

| Trudy | An intruder. |

| Victor[19] or Vanna[28] | A verifier, who requires proof from the prover. |

| Walter | A warden, who may guard Alice and Bob. |

| Wendy | A whistleblower, who is an insider with privileged access capable of divulging information. |

Interactive proof systems

editFor interactive proof systems there are other characters:

| Arthur and Merlin | Merlin provides answers, and Arthur asks questions.[29] Merlin has unbounded computational ability (like the wizard Merlin). In interactive proof systems, Merlin claims the truth of a statement, and Arthur (like King Arthur), questions him to verify the claim. |

| Paul and Carole | Paul asks questions, and Carole provides answers. In the solution of the Twenty Questions problem,[30] Paul (standing in for Paul Erdős) asked questions and Carole (an anagram of "oracle") answered them. Paul and Carole were also used in combinatorial games, in the roles of pusher and chooser.[31] |

| Arthur and Bertha | Arthur is the "left", "black", or "vertical" player, and Bertha is the "right", "white", or "horizontal" player in a combinatorial game. Additionally, Arthur, given the same outcome, prefers a game to take the fewest moves, while Bertha prefers a game to take the most moves.[32] |

Physics

editThe names Alice and Bob are often used to name the participants in thought experiments in physics.[33][34] More alphabetical names, usually of alternating gender, are used as required, e.g. "Alice and Bob (and Carol and Dick and Eve)".[35]

In experiments involving robotic systems, the terms "Alice Robot" and "Bob Robot" refer to mobile platforms responsible for transmitting quantum information and receiving it with quantum detectors, respectively, within the context of the field of quantum robotics.[36][37][38][39][40][41]

See also

editReferences

edit- ^ R. Shirey (August 2007). Internet Security Glossary, Version 2. Network Working Group. doi:10.17487/RFC4949. RFC 4949. Informational.

- ^ a b c d Rivest, Ron L.; Shamir, Adi; Adleman, Len (February 1, 1978). "A Method for Obtaining Digital Signatures and Public-key Cryptosystems". Communications of the ACM. 21 (2): 120–126. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.607.2677. doi:10.1145/359340.359342. ISSN 0001-0782. S2CID 2873616.

- ^ Newton, David E. (1997). Encyclopedia of Cryptography. Santa Barbara California: Instructional Horizons, Inc. p. 10.

- ^ Rivest, Ron L.; Shamir, Adi; Adleman, Len (April 1977). On Digital Signatures and Public-Key Cryptosystems. Cambridge MA: Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

- ^ Rivest, Ron L.; Shamir, Adi; Adleman, Len (September 20, 1983) [1977]. Cryptographic Communications System and Method. Cambridge MA. 4405829.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Brown, Bob (February 7, 2005). "Security's inseparable couple: Alice & Bob". NetworkWorld.

- ^ Rabin, Michael O. (1981). How to exchange secrets with oblivious transfer. Aiken Computation Lab, Harvard University. Technical Report TR-81.

- ^ Blum, Manuel (November 10, 1981). "Coin Flipping by Telephone a Protocol for Solving Impossible Problems". ACM SIGACT News. 15 (1): 23–27. doi:10.1145/1008908.1008911. S2CID 19928725.

- ^ Blum, Manuel (1983). "How to exchange (Secret) keys". ACM Transactions on Computer Systems. 1 (2): 175–193. doi:10.1145/357360.357368. S2CID 16304470.

- ^ Cattaneoa, Giuseppe; De Santisa, Alfredo; Ferraro Petrillo, Umberto (April 2008). "Visualization of cryptographic protocols with GRACE". Journal of Visual Languages & Computing. 19 (2): 258–290. doi:10.1016/j.jvlc.2007.05.001.

- ^ Gordon, John (April 1984). "The Alice and Bob After Dinner Speech". Zurich.

- ^ Bennett, Charles H.; Brassard, Gilles; Robert, Jean-Marc (1988). "Privacy Amplification by Public Discussion". SIAM Journal on Computing. 17 (2): 210–229. doi:10.1137/0217014. S2CID 5956782.

- ^ Schneier, Bruce (2015). Applied Cryptography: Protocols, Algorithms and Source Code in C. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-0-471-59756-8.

- ^ Xue, Peng; Wang, Kunkun; Wang, Xiaoping (2017). "Efficient multiuser quantum cryptography network based on entanglement". Scientific Reports. 7 (1): 45928. Bibcode:2017NatSR...745928X. doi:10.1038/srep45928. ISSN 2045-2322. PMC 5379677. PMID 28374854. An example from quantum cryptography with Alice, Bob, Carol, and David.

- ^ Tanenbaum, Andrew S. (2007). Distributed Systems: Principles and Paradigms. Pearson Prentice Hall. p. 171;399–402. ISBN 978-0-13-239227-3.

- ^ Cho, Hyunghoon; Ippolito, Daphne; Yun William Yu (2020). "Contact Tracing Mobile Apps for COVID-19: Privacy Considerations and Related Trade-offs". arXiv:2003.11511 [cs.CR].

- ^ Fried, Joshua; Gaudry, Pierrick; Heninger, Nadia; Thomé, Emmanuel (2017). "A Kilobit Hidden SNFS Discrete Logarithm Computation". Advances in Cryptology – EUROCRYPT 2017 (PDF). Lecture Notes in Computer Science. Vol. 10, 210. University of Pennsylvania and INRIA, CNRS, University of Lorraine. pp. 202–231. arXiv:1610.02874. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-56620-7_8. ISBN 978-3-319-56619-1. S2CID 12341745. Retrieved October 12, 2016.

- ^ Grigg, Ian (November 24, 2002). "Ivan The Honourable". iang.org.

- ^ a b Schneier, Bruce (1996). Applied Cryptography: Protocols, Algorithms, and Source Code in C (Second ed.). Wiley. p. 23. ISBN 978-0-471-11709-4. Table 2.1: Dramatis Personae.

- ^ Szabo, Nick (September 1997). "Formalizing and Securing Relationships on Public Networks". First Monday. 2 (9). doi:10.5210/fm.v2i9.548. S2CID 33773111.

- ^ Schneier, Bruce (September 23, 2010), "Who are Alice & Bob?", YouTube, archived from the original on December 22, 2021, retrieved May 2, 2017

- ^ Schneier, Bruce (1994). Applied Cryptography: Protocols, Algorithms, and Source Code in C. Wiley. p. 44. ISBN 978-0-471-59756-8.

Mallet can intercept Alice's database inquiry, and substitute his own public key for Alice's. He can do the same to Bob.

- ^ Perkins, Charles L.; et al. (2000). Firewalls: 24seven. Network Press. p. 130. ISBN 9780782125290.

Mallet maintains the illusion that Alice and Bob are talking to each other rather than to him by intercepting the messages and retransmitting them.

- ^ LaMacchia, Brian (2002). .NET Framework Security. Addison-Wesley. p. 616. ISBN 9780672321849.

Mallet represents an active adversary that not only listens to all communications between Alice and Bob but can also modify the contents of any communication he sees while it is in transit.

- ^ Dolev, Shlomi, ed. (2009). Algorithmic Aspects of Wireless Sensor Networks. Springer. p. 67. ISBN 9783642054334.

We model key choices of Alice, Bob and adversary Mallet as independent random variables A, B and M [...]

- ^ Stallings, William (1998). Cryptography and Network Security: Principles and Practice. Pearson. p. 317. ISBN 978-0133354690.

Suppose Alice and Bob wish to exchange keys, and Darth is the adversary.

- ^ "A Collaborative Access Control Framework for Online Social Networks" (PDF).

- ^ Lund, Carsten; et al. (1992). "Algebraic Methods for Interactive Proof Systems". Journal of the ACM. 39 (4): 859–868. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.41.9477. doi:10.1145/146585.146605. S2CID 207170996.

- ^ Babai, László; Moran, Shlomo (April 1988). "Arthur-Merlin games: A randomized proof system, and a hierarchy of complexity classes". Journal of Computer and System Sciences. 36 (2): 254–276. doi:10.1016/0022-0000(88)90028-1.

- ^ Spencer, Joel; Winkler, Peter (1992), "Three Thresholds for a Liar", Combinatorics, Probability and Computing, 1 (1): 81–93, doi:10.1017/S0963548300000080, S2CID 45707043

- ^ Muthukrishnan, S. (2005). Data Streams: Algorithms and Applications. Now Publishers. p. 3. ISBN 978-1-933019-14-7.[permanent dead link]

- ^ Conway, John Horton (2000). On Numbers and Games. CRC Press. pp. 71, 175, 176. ISBN 9781568811277.

- ^ "Alice and Bob communicate without transferring a single photon". physicsworld.com. April 16, 2013. Retrieved June 19, 2017.

- ^ Frazier, Matthew; Taddese, Biniyam; Antonsen, Thomas; Anlage, Steven M. (February 7, 2013). "Nonlinear Time Reversal in a Wave Chaotic System". Physical Review Letters. 110 (6): 063902. arXiv:1207.1667. Bibcode:2013PhRvL.110f3902F. doi:10.1103/physrevlett.110.063902. PMID 23432243. S2CID 35907279.

- ^ David Mermin, N. (March 5, 2000). "209: Notes on Special Relativity" (PDF). An example with several names.

- ^ Farbod Khoshnoud, Lucas Lamata, Clarence W. De Silva, Marco B. Quadrelli, Quantum Teleportation for Control of Dynamic Systems and Autonomy, Journal of Mechatronic Systems and Control, Volume 49, Issue 3, pp. 124-131, 2021.

- ^ Lamata, Lucas; Quadrelli, Marco B.; de Silva, Clarence W.; Kumar, Prem; Kanter, Gregory S.; Ghazinejad, Maziar; Khoshnoud, Farbod (October 12, 2021). "Quantum Mechatronics". Electronics. 10 (20): 2483. doi:10.3390/electronics10202483.

- ^ Farbod Khoshnoud, Maziar Ghazinejad, Automated quantum entanglement and cryptography for networks of robotic systems, IEEE/ASME International Conference on Mechatronic and Embedded Systems and Applications (MESA), IDETC-CIE 2021, Virtual Conference: August 17 – 20, DETC2021-71653, 2021.

- ^ Khoshnoud, Farbod; Aiello, Clarice; Quadrelli, Bruno; Ghazinejad, Maziar; De Silva, Clarence; Khoshnoud, Farbod; Bahr, Behnam; Lamata, Lucas (April 23, 2021). Modernizing Mechatronics course with Quantum Engineering. 2021 ASEE Pacific Southwest Conference - "Pushing Past Pandemic Pedagogy: Learning from Disruption". ASEE Conferences. doi:10.18260/1-2--38241. PDF

- ^ Khoshnoud, Farbod; Esat, Ibrahim I.; de Silva, Clarence W.; Quadrelli, Marco B. (April 2019). "Quantum Network of Cooperative Unmanned Autonomous Systems". Unmanned Systems. 07 (2): 137–145. doi:10.1142/S2301385019500055. ISSN 2301-3850. S2CID 149842737. Retrieved September 7, 2023.

- ^ Farbod Khoshnoud, Marco B. Quadrelli, Enrique Galvez, Clarence W. de Silva, Shayan Javaherian, B. Bahr, M. Ghazinejad, A. S. Eddin, M. El-Hadedy, Quantum Brain-Computer Interface, ASEE PSW, 2023, in press.

External links

edit- History of Alice and Bob

- A Method for Obtaining Digital Signatures and Public-Key Cryptosystems Archived December 17, 2008, at the Wayback Machine

- The Alice and Bob After-Dinner Speech, given at the Zurich Seminar, April 1984, by John Gordon

- Geek Song: "Alice and Bob"

- Alice and Bob jokes (mainly Quantum Computing-related)

- A short history of Bobs (story and slideshow) in the computing industry, from Alice & Bob to Microsoft Bob and Father of Ethernet Bob Metcalfe

- XKCD #177: Alice and Bob