A city block, residential block, urban block, or simply block is a central element of urban planning and urban design.

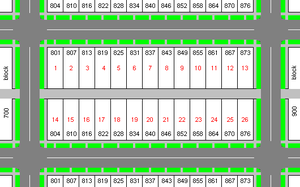

In a city with a grid system, the block is the smallest group of buildings that is surrounded by streets. City blocks are the space for buildings within the street pattern of a city, and form the basic unit of a city's urban fabric. City blocks may be subdivided into any number of smaller land lots usually in private ownership, though in some cases, it may be other forms of tenure. City blocks are usually built-up to varying degrees and thus form the physical containers or "streetwalls" of public space. Most cities are composed of a greater or lesser variety of sizes and shapes of urban block. For example, many pre-industrial cores of cities in Europe, Asia, and the Middle East tend to have irregularly shaped street patterns and urban blocks, while cities based on grids have much more regular arrangements.

By extension, the word "block" is an important informal unit of length equal to the distance between two streets of a street grid.

Grid plan

editIn most cities of the New World that were planned rather than developing gradually over a long period of time, streets are typically laid out on a grid plan of square or rectangular city blocks. Using the perimeter block development principle, city blocks are developed so that buildings are located along the perimeter of the block, with entrances facing the street, and semi-private courtyards in the rear of the buildings.[1] This historic arrangement reflects organic development of structures and land usage, adapted to urban planning.

Since the spacing of streets in grid plans varies so widely among cities, or even within cities, it is difficult to generalize about the size of a city block. Oblong blocks range considerably in width and length. The standard block in Manhattan is about 264 by 900 feet (80 m × 274 m). In Chicago, a typical city block is 330 by 660 feet (100 m × 200 m),[2] meaning that 16 east-west blocks or 8 north-south blocks measure one mile, which has been adopted by other US cities. In much of the United States and Canada, the addresses follow a block and lot number system, in which each block of a street is allotted 100 building numbers. The blocks in central Melbourne, Australia, are also 330 by 660 feet (100 m × 200 m), formed by splitting the square blocks in an original grid with a narrow street down the middle.

Many Old World cities have grown by accretion over time rather than being planned, making rectangular city blocks uncommon in the innermost development among most European cities, for example. An exception is represented by those cities that were founded as Roman military settlements, and that often preserve the original grid layout around two main orthogonal axes (such as Turin, Italy) and cities heavily damaged during World War II (like Frankfurt). Following the example of Philadelphia, New York City adopted the Commissioners' Plan of 1811 for a more extensive grid plan.

Structure variations

editSome variations of the interpretation of city blocks include superblocks, subblocks, and perimeter blocks.

Superblock

editA superblock, or super-block, is an area of urban land that is bounded by arterial roads and the size of multiple typically sized city blocks.[3] Within the superblock, the local road network, if any, is designed to serve only local needs.

Superblocks can also contain an orthogonal internal road network, including those based on a grid plan or quasi-grid plan. That typology is prevalent in Japan and China, for example. Chen defines the supergrid and superblock urban morphology in that context as follows:

"The Supergrid is a large-scale net of wide roads that defines a series of cells or Superblocks, each containing a network of narrower streets."[4]

Superblocks can also be retroactively superimposed on pre-existing grid plan by changing the traffic rules and streetscape of internal streets within the superblock, as in the case of Barcelona's superilles (Catalan for superblocks).[5] Each superilla has nine city blocks, with speed limits on the internal roads slowed to 10–20 km/h (6.2–12.4 mph), through traffic disallowed, and through travel possible only on the perimeter roads.[6]

Sub-structure

editIn a geoprocessing perspective there are two complementary ways of modeling city blocks:

- with sidewalks: using a direct geometric representation of the usual concept of city blocks. Not only sidewalks, but also inner alleys, common gardens, etc. Some street parts, such as a street greenway, isolated and with no related lot, can be also represented as a block without sidewalks.

- without sidewalks: represented by polygon obtained by the external border of the union of a set of touching land lots (illustration opposite).

A block without sidewalks is always within a block with sidewalks. The geometric subtraction of a block without sidewalks from block with sidewalks, contains the sidewalk, the alley, and any other non-lot sub-structure.

Perimeter block

editA perimeter block is a type of city block which is built up on all sides surrounding a central space that is semi-private. They may contain a mixture of uses, with commercial or retail functions on the ground floor. Perimeter blocks are a key component of many European cities and are an urban form that allows very high urban densities to be achieved without high-rise buildings.[7]

Use of term

editAs an informal unit of distance

editIn North American English and Australian English, the word "block" is used as an informal unit of distance.[8] For example, someone giving directions might say, "It's three blocks from here", meaning either literally three blocks distant (in a city grid) or the equivalent of three blocks without a grid.

Since there is no standard dimension for city blocks, and they are typically rectangular in shape, meaning a block and one direction is a different length than a block in another, colloquial directions involving blocks as proxies for measurements in feet or meters are obviously both imprecise and relative.

See also

editReferences

edit- ^ Frey, Hildebrand (1999). Designing the City: Towards a More Sustainable Urban Form. E & FN Spon. ISBN 978-0-419-22110-4.

- ^ cityofchicago.org

- ^ Eggimann Sven (2025), "Deprioritising cars beyond rerouting: Future research directions of the Barcelona Superblock", Cities, vol. 157, doi:10.1016/j.cities.2024.105609

- ^ Xiaofei, Chen (2017-08-29). A Comparative Study of Supergrid and Superblock Urban Structure in China and Japan Rethinking the Chinese Superblocks: Learning from Japanese Experience (Thesis). hdl:2123/17986.

- ^ Eggimann Sven (2022), "The potential of implementing superblocks for multifunctional street use in cities", Nature Sustainability, vol. 5, no. 5, pp. 406–414, Bibcode:2022NatSu...5..406E, doi:10.1038/s41893-022-00855-2, PMC 7612763, PMID 35614932

- ^ Bausells, Marta (2016-05-17). "Superblocks to the rescue: Barcelona's plan to give streets back to residents". The Guardian. Retrieved 2018-04-14.

- ^ Edwards, Brian: "The European perimeter block" in Courtyard Housing: Past, Present and Future, Taylor & Francis, 2004

- ^ Imagination: The Science of Your Mind's Greatest Power, by Jim Davies

Further reading

edit- Jacobs, Jane (1961). The Death and Life of Great American Cities. Random House.

- The Great American Grid: Block Size Dimensions Archived 2019-11-03 at the Wayback Machine