Gastric dilatation volvulus (GDV), also known as gastric dilation, twisted stomach, or gastric torsion, is a medical condition that affects dogs and rarely cats and guinea pigs,[1] in which the stomach becomes overstretched and rotated by excessive gas content. The condition also involves compression of the diaphragm and caudal vena cavae. The word bloat is often used as a general term to mean gas distension without stomach torsion (a normal change after eating), or to refer to GDV.

GDV is a life-threatening condition in dogs that requires prompt treatment. It is common in certain breeds; deep-chested breeds are especially at risk. Mortality rates in dogs range from 10 to 60%, even with treatment.[2] With surgery, the mortality rate is 15 to 33 percent.[3]

Symptoms

editSymptoms are not necessarily distinguishable from other kinds of distress. A dog might stand uncomfortably and seem to be in extreme discomfort for no apparent reason. Other possible symptoms include firm distension of the abdomen, weakness, depression, difficulty breathing, hypersalivation, and retching without producing any vomitus (nonproductive vomiting). Many dogs with GDV have cardiac arrhythmias (40% in one study).[4] Chronic GDV in dogs, include symptoms such as loss of appetite, vomiting, and weight loss.[5] Hypovolaemia may occur and in severe cases hypovolaemic shock and hypoperfusion.[1]

Blood dyscrasias have been identified in patients with GDV. Haemological conditions that may be identified include: neutrophilic leukocytosis, lymphopaenia, leukopaenia, thrombocytopaenia, and haemoconcentration. Other conditions include: hepatocelluar damage, cholestasis, azotemia and hypokalaemia.[1]

Causes

editGastric dilatation volvulus is multifactorial without any one cause being identified, but in all cases the immediate prerequisite is a dysfunction of the sphincter between the esophagus and stomach and an obstruction of outflow through the pylorus.[6][1]

Hypergastrinaemia has been hypothesised as a cause of GDV. Pyloric hypertrophy as a result of hypergastrinaemia was presumed to cause pyloric outflow obstruction, retarding gastric emptying. Studies have not found evidence to support this theory.[1] One study found no association between pyloric hypertrophy and GDV.[7]

Impairment of gastric myoelectricity retarding gastric emptying has been hypothesised as a cause of GDV. Currently no study has identified an association between gastric myoelectricity and GDV.[1]

Risk factors

editDog breeds that have a higher depth to width ratio of the thorax are significantly more likely to acquire GDV than other breeds. If there is a family history of the condition the risk is even more severe, highlighting a heritability to the predisposing factors. Body weight is a factor with obese dogs being less likely to develop GDV than healthy or underweight dogs.[1]

Stress is known to impair gastrointestinal function. Stress has been identified as a risk factor for GDV, the exact manner for this is not currently known.[1][8]

Other risk factors include: nasal mite infection;[9] gastrointestinal disease;[10] and inflammatory bowel disease, with 61% of dogs with GDV having inflammatory bowel disease identified via biopsy in one study.[11]

The breeds most likely to develop GDV are the Great Dane (10 times more likely), Weimaraner (4.6) St Bernard (4.2) and the Irish Setter (3.5).[12] Other breeds with a predisposition include the Irish Wolfhound, Borzoi, English Mastiff, Akita, Bull Mastiff, pointing dogs, Bloodhound, Grand Bleu de Gascogne and the standard Poodle.[1] The Great Dane has been found to have a lifetime risk of 42.4% in one study,[10] which has led to the Great Dane being the focus of investigations into causes and risk factors for GDV.[1] One study has found certain alleles of the DLA88, DRB1 and TLR5 genes, which are part of the canine immune system, to predispose a dog to GDV.[13] Further studies have associated these alleles with greater diversity in the gut microbiome and an increased risk of GDV.[14]

GDV has been reported across the age range in dogs. It is more likely to occur in older dogs but is not a geriatric disease and the risk plateaus after the first 2–4 years for large dogs.[1]

Dietary factors

editOne common recommendation in the past has been to raise the food bowl of dogs when they eat, but this was shown to increase the risk in one study.[15] Eating only once daily[16] and eating food consisting of particles less than 30 mm (1.2 in) in size also has been shown increase the risk of GDV.[17] One study looking at the ingredients of dry dog food found that while neither grains, soy, nor animal proteins increased risk of bloat, foods containing an increased amount of added oils or fats do increase the risk, possibly owing to delayed emptying of the stomach.[18]

Pathophysiology

editThe exact pathophysiology is not understood. It is still unknown what order the condition occurs: whether dilatation or volvulus occurs first.[1]

The stomach twists around the longitudinal axis of the digestive tract, also known as volvulus.[6] The most common direction for rotation is clockwise, viewing the animal from behind. The stomach can rotate up to 360° in this direction and 90° counterclockwise. If the volvulus is greater than 180°, the esophagus is closed off, thereby preventing the animal from relieving the condition by belching or vomiting.[19] The results of this distortion of normal anatomy and gas distension include hypotension (low blood pressure), decreased return of blood to the heart, ischemia (loss of blood supply) of the stomach, and shock. Pressure on the portal vein decreases blood flow to liver and decreases the ability of that organ to remove toxins and absorbed bacteria from the blood.[20] Rotations of up to 360° have been reported but typically rotations stop around 270°.[1]

Diagnosis

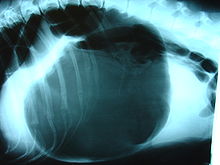

editA diagnosis of GDV is made by several factors. The breed and history often gives a significant suspicion of the condition, and a physical examination often reveals the telltale sign of a distended abdomen with abdominal tympany. Shock is diagnosed by the presence of pale mucous membranes with poor capillary refill, increased heart rate, and poor pulse quality. Radiographs (X-rays), usually taken after decompression of the stomach if the dog is unstable, shows a stomach distended with gas. The pylorus, which normally is ventral and to the right of the body of the stomach, is cranial to the body of the stomach and left of the midline, often separated on the X-ray by soft tissue and giving the appearance of a separate gas-filled pocket (double-bubble sign).[5]

Treatment

editPatients with GDV need to be stabilised as soon as possible. Perfusion and blood pressure need to be normalised before any further treatment can be performed. Analgesia should also be provided.[1]

Patients require intravenous fluid therapy with saline. Colloid fluids may be required if the patient does not respond well to the crystalloid solution. Antiarrhythmic drugs should be administered after starting fluid therapy to stabilise blood pressure. Other drugs such as dobutamine should be provided if blood pressure fails to normalise, only as a last resort. Other vasopressors can be used such as ephedrine, phenylephrine, and epinephrine.[1]

Percutaneous decompression is the easiest method of treating GDV. A large catheter is inserted into the gastric lumen. If done incorrectly the spleen may be lacerated or punctured. Potentially the content of the stomach may leak if the procedure is performed incorrectly.[1]

Orogastric intubation is another method for treatment. An orogastric tube is entered into the stomach via the oesophageal sphincter, tepid water is sent as a bolus through the tube into the stomach to lavage it. Fluid should be regurgitated up the tube. If it is not then a stomach perforation has likely occurred.[1]

To restore the stomach to the normal position an exploratory laparotomy (explap) is needed. Sometimes a gastrectomy may be required. During the explap the stomach is rotated up to 360° to put it back into the right position, although typically such extreme rotation is not needed. Pulling on the pylorus allows for the stomach to be repositioned. Sometimes the dilatation is serious enough that the stomach requires further decompression before repositioning. Other organs of the digestive system are assessed during the procedure. Splenectomy may be required. Gastropexy involves suturing the pyloric antrum to the abdominal wall to prevent recurrence of GDV. Patients that do not receive a gastropexy have a high likelihood of GDV recurrence with one study finding 80% of dogs that suffered a GDV but did not undergo a gastropexy having GDV reoccur.[1]

Prevention

editRecurrence of GDV attacks can be a problem, occurring in up to 80% of dogs treated medically only (without surgery).[21] To prevent recurrence, at the same time the bloat is treated surgically, a right-side gastropexy is often performed, which by a variety of methods firmly attaches the stomach wall to the body wall, to prevent it from twisting inside the abdominal cavity in the future. While dogs that have had gastropexies still may develop gas distension of the stomach, a significant reduction in recurrence of gastric volvulus is seen. Of 136 dogs that had surgery for gastric dilatation-volvulus, six that did have gastropexies had a recurrence, while 74 (54.5%) of those without the additional surgery recurred.[22] Gastropexies are also performed prophylactically in dogs considered to be at high risk of GDV, including dogs with previous episodes or with gastrointestinal disease predisposing to GDV, and dogs with a first-order relative (parent or sibling) with a history of it.[21]

Precautions that are likely to help prevent gastric dilatation-volvulus include feeding small meals throughout the day instead of one big meal, and not exercising immediately before or after a meal.[23]

Prognosis

editImmediate treatment is the most important factor in a favorable prognosis. A delay in treatment greater than 6 hours or the presence of peritonitis, sepsis, hypotension, or disseminated intravascular coagulation are negative prognostic indicators.[3] Patients that lack the ability to walk are 4.4 times more likely to die. Comatose patients are 36 times more likely to die. Dogs that show depression when presented are three times more likely to die.[1]

Historically, GDV has held a guarded prognosis.[24] Although "early studies showed mortality rates between 33 and 68% for dogs with GDV," studies from 2007 to 2012 "reported mortality rates between 10 and 26.8%".[25] Mortality rates approach 10 to 40% even with treatment.[26] With prompt treatment and good preoperative stabilization of the patient, mortality is significantly lessened to 10% overall (in a referral setting).[27] Negative prognostic indicators following surgical intervention include postoperative cardiac arrhythmia, splenectomy, or splenectomy with partial gastric resection. A longer time from presentation to surgery was associated with a lower mortality, presumably because these dogs had received more complete preoperative fluid resuscitation, thus were better cardiovascularly stabilized prior to the procedure.[27]

Prognosis is guarded if the cardia is necrotic.[1] Many dogs are euthanised due to risks of performing surgery or inability to afford costly surgery and treatment.[1]

Epidemiology

editAs a general rule, GDV is of greatest risk to deep-chested dogs. The five breeds at greatest risk are Great Danes, Weimaraners, St. Bernards, Gordon Setters, and Irish Setters.[12] In fact, the lifetime risk for a Great Dane to develop GDV has been estimated to be close to 37%.[28] Standard Poodles are also at risk for this health problem,[19] as are Irish Wolfhounds, German Shorthaired Pointers, German Shepherds, and Rhodesian Ridgebacks. Basset Hounds and Dachshunds have the greatest risk for dogs less than 50 lb (23 kg).[2]

Society and culture

edit- In the novel and film Marley & Me, Marley develops and ultimately dies of "bloat".[29]

- In "Dog of Death," an episode of the animated TV series The Simpsons, the family dog Santa's Little Helper develops a "twisted stomach", necessitating surgery.[30]

References

edit- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u Monnet, Eric; Mazzaferro, Elisa M (2023-05-31). "Gastric dilatation volvulus syndrome". Small Animal Soft Tissue Surgery. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons. pp. 53–74. ISBN 978-1-119-69368-0.

- ^ a b Aronson, Lillian R.; Brockman, Daniel J.; Brown, Dorothy Cimino (2000). "Gastrointestinal Emergencies". The Veterinary Clinics of North America. 30 (1): 558–569. doi:10.1016/s0195-5616(00)50039-4. PMC 1374121. PMID 10853276.

- ^ a b Beck J, Staatz A, Pelsue D, Kudnig S, MacPhail C, Seim H, Monnet E (2006). "Risk factors associated with short-term outcome and development of perioperative complications in dogs undergoing surgery because of gastric dilatation-volvulus: 166 cases (1992-2003)". J. Am. Vet. Med. Assoc. 229 (12): 1934–9. doi:10.2460/javma.229.12.1934. PMID 17173533.

- ^ Brockman D, Washabau R, Drobatz K (1995). "Canine gastric dilatation/volvulus syndrome in a veterinary critical care unit: 295 cases (1986-1992)". J. Am. Vet. Med. Assoc. 207 (4): 460–4. PMID 7591946.

- ^ a b Fossum, Theresa W. (2006). "Gastric Dilatation Volvulus: What's New?" (PDF). Proceedings of the 31st World Congress. World Small Animal Veterinary Association. Retrieved 2007-04-17.

- ^ a b Parton A, Volk S, Weisse C (2006). "Gastric ulceration subsequent to partial invagination of the stomach in a dog with gastric dilatation-volvulus". J. Am. Vet. Med. Assoc. 228 (12): 1895–900. doi:10.2460/javma.228.12.1895. PMID 16784379.

- ^ GREENFIELD, CATHY L.; WALSHAW, RICHARD; THOMAS, MICHAEL W. (1989). "Significance of the Heineke‐Mikulicz Pyloroplasty in the Treatment of Gastric Dilatation‐Volvulus A Prospective Clinical Study". Veterinary Surgery. 18 (1). Wiley: 22–26. doi:10.1111/j.1532-950x.1989.tb01038.x. ISSN 0161-3499.

- ^ Elwood, C. M. (1998). "Risk factors for gastric dilatation in Irish setter dogs". Journal of Small Animal Practice. 39 (4): 185–190. doi:10.1111/j.1748-5827.1998.tb03627.x. ISSN 0022-4510.

- ^ Bredal, W.P. (1998). "Pneumonyssoides caninum infection--a risk factor for gastric dilatation-volvulus in dogs". Veterinary Research Communications. 22 (4). Springer Science and Business Media LLC: 225–231. doi:10.1023/a:1006083013513. ISSN 0165-7380.

- ^ a b Glickman L, Glickman N, Schellenberg D, Raghavan M, Lee T (2000). "Incidence of and breed-related risk factors for gastric dilatation-volvulus in dogs". J. Am. Vet. Med. Assoc. 216 (1): 40–5. doi:10.2460/javma.2000.216.40. PMID 10638316.

- ^ Braun, L; Lester, S; Kuzma, AB; Hosie, SC (1996-07-01). "Gastric dilatation-volvulus in the dog with histological evidence of preexisting inflammatory bowel disease: a retrospective study of 23 cases". Journal of the American Animal Hospital Association. 32 (4). American Animal Hospital Association: 287–290. doi:10.5326/15473317-32-4-287. ISSN 0587-2871.

- ^ a b Glickman L, Glickman N, Pérez C, Schellenberg D, Lantz G (1994). "Analysis of risk factors for gastric dilatation and dilatation-volvulus in dogs". J. Am. Vet. Med. Assoc. 204 (9): 1465–71. PMID 8050972.

- ^ Harkey, Michael A.; Villagran, Alexandra M.; Venkataraman, Gopalakrishnan M.; Leisenring, Wendy M.; Hullar, Meredith A. J.; Torok-Storb, Beverly J. (2017). "Associations between gastric dilatation-volvulus in Great Danes and specific alleles of the canine immune-system genes DLA88, DRB1, and TLR5". American Journal of Veterinary Research. 78 (8). American Veterinary Medical Association (AVMA): 934–945. doi:10.2460/ajvr.78.8.934. ISSN 0002-9645.

- ^ Hullar, Meredith A. J.; Lampe, Johanna W.; Torok-Storb, Beverly J.; Harkey, Michael A. (2018-06-11). "The canine gut microbiome is associated with higher risk of gastric dilatation-volvulus and high risk genetic variants of the immune system". PLOS ONE. 13 (6). Public Library of Science (PLoS): e0197686. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0197686. ISSN 1932-6203.

- ^ Glickman L, Glickman N, Schellenberg D, Raghavan M, Lee T (2000). "Non-dietary risk factors for gastric dilatation-volvulus in large and giant breed dogs". J. Am. Vet. Med. Assoc. 217 (10): 1492–9. doi:10.2460/javma.2000.217.1492. PMID 11128539. S2CID 22006972.

- ^ Glickman L, Glickman N, Schellenberg D, Simpson K, Lantz G (1997). "Multiple risk factors for the gastric dilatation-volvulus syndrome in dogs: a practitioner/owner case-control study". Journal of the American Animal Hospital Association. 33 (3): 197–204. doi:10.5326/15473317-33-3-197. PMID 9138229.

- ^ Theyse L, van de Brom W, van Sluijs F (1998). "Small size of food particles and age as risk factors for gastric dilatation volvulus in great danes". Vet. Rec. 143 (2): 48–50. doi:10.1136/vr.143.2.48. PMID 9699253.

- ^ Raghavan M, Glickman N, Glickman L (2006). "The effect of ingredients in dry dog foods on the risk of gastric dilatation-volvulus in dogs". Journal of the American Animal Hospital Association. 42 (1): 28–36. doi:10.5326/0420028. PMID 16397192.

- ^ a b "Gastric Dilatation-volvulus". The Merck Veterinary Manual. 2006. Retrieved 2007-04-17.

- ^ Bright, Ronald M. (2004). "Gastric dilatation-volvulus: risk factors and some new minimally invasive gastropexy techniques". Proceedings of the 29th World Congress of the World Small Animal Veterinary Association. Retrieved 2007-04-17.

- ^ a b Rawlings C, Mahaffey M, Bement S, Canalis C (2002). "Prospective evaluation of laparoscopic-assisted gastropexy in dogs susceptible to gastric dilatation". J. Am. Vet. Med. Assoc. 221 (11): 1576–81. doi:10.2460/javma.2002.221.1576. PMID 12479327.

- ^ Glickman L, Lantz G, Schellenberg D, Glickman N (1998). "A prospective study of survival and recurrence following the acute gastric dilatation-volvulus syndrome in 136 dogs". Journal of the American Animal Hospital Association. 34 (3): 253–9. doi:10.5326/15473317-34-3-253. PMID 9590454.

- ^ Wingfield, Wayne E. (1997). Veterinary Emergency Medicine Secrets. Hanley & Belfus, Inc. ISBN 978-1-56053-215-6.

- ^ "Canine Bloat: Gastric Dilatation and Volvulus (GDV): 'The Mother of All Emergencies'". marylandpetemergency.com. Animal Emergency Hospital. Retrieved October 15, 2017.

- ^ Przywara, John F.; Abel, Steven B.; Peacock, John T.; Shott, Susan (October 2014). "Occurrence and recurrence of gastric dilatation with or without volvulus after incisional gastropexy". Can Vet J. 55 (10): 981–984. PMC 4187373. PMID 25320388.

- ^ "Bloat". aspca.org. The American Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals. Archived from the original on July 1, 2014. Retrieved 15 October 2017.

- ^ a b Mackenzie G, Barnhart M, Kennedy S, DeHoff W, Schertel E (March–April 2010). "A retrospective study of factors influencing survival following surgery for gastric dilatation-volvulus syndrome in 306 dogs". Journal of the American Animal Hospital Association. 46 (2): 97–102. doi:10.5326/0460097. PMID 20194364.

- ^ Ward M, Patronek G, Glickman L (2003). "Benefits of prophylactic gastropexy for dogs at risk of gastric dilatation-volvulus". Prev. Vet. Med. 60 (4): 319–29. doi:10.1016/S0167-5877(03)00142-9. PMID 12941556.

- ^ Lucas, D (15 September 2014). "'Bloat' refers to 2 different stomach ailments in pets". USA TODAY. Retrieved 2017-07-28.

- ^ "The Simpsons - 'Dog of Death'". cwsanfrancisco.cbslocal.com. KBCW/CBS Local. 15 March 2014. Retrieved 29 July 2017.