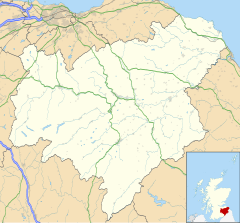

Biggar (Scottish Gaelic: Bigear [ˈpikʲəɾ])[2] is a town, parish and former burgh in South Lanarkshire, Scotland, in the Southern Uplands near the River Clyde on the A702. The closest neighbouring towns are Lanark, Peebles and Carluke.

Biggar

| |

|---|---|

| |

| Population | 2,640 (2022)[1] |

| OS grid reference | NT045375 |

| • Edinburgh | 26 mi (42 km) |

| • London | 317 mi (510 km) |

| Civil parish |

|

| Council area | |

| Lieutenancy area | |

| Country | Scotland |

| Sovereign state | United Kingdom |

| Post town | BIGGAR |

| Postcode district | ML12 |

| Police | Scotland |

| Fire | Scottish |

| Ambulance | Scottish |

| UK Parliament | |

| Scottish Parliament | |

History

editBiggar occupies a key location close to two of Scotland's great rivers, the Clyde flowing to the west, and the Tweed flowing to the east. Stone and Bronze-age artefacts have been found in the area but the strongest evidence of settlement occurs on the hills surrounding the town. One of these is Bizzyberry Hill where Iron Age remains dating back almost 2,000 years have been found.[3] The present day A702 follows the route of a Roman road, which linked the Clyde Valley with Musselburgh.

In the 12th century, in return for the promise of support, King David I gave the lands of Biggar to Baldwin, a Fleming leader. He built a motte and bailey castle, which can still be seen north-west of the High Street.[3] The first permanent crossing of the Biggar Burn was also built. It is thought that there has been a church at Biggar since the 6th or 7th century, although the first stone kirk was built in 1164, on the site of the existing kirk.

In the 14th century, the Fleming family were given lands in the area by Robert the Bruce, whose cause they had supported. The Flemings built Boghall Castle, visible as a ruin until the early 20th century, but now only represented by a few mounds. The town continued to grow as an important market town, and in 1451 it became a burgh. The market place remains the central focus of the town. The kirk was rebuilt as a Collegiate church in 1546 for Malcolm, 3rd Lord Fleming, the last to be established before the Reformation of 1560. The Flemings found themselves on the wrong side in the 16th century, when they supported Mary, Queen of Scots. Their lands remained in the Fleming family until the 18th century when the male line of succession ended. The lands passed into the Elphinstone family in 1735 on the marriage of the heiress Lady Clementina Fleming to Charles, Lord Elphinstone.

Biggar Gas Works opened in 1836, producing gas from coal. In 1973, with the introduction of natural gas, the works closed. Biggar had its own railway station on the Symington, Biggar and Broughton Railway between 1860 and 1953.

In 1899 farmers, Thomas Blackwood Murray and Norman Fulton, located in Biggar founded Albion Motors as a small business which eventually grew into the largest truck company in the British Empire. The company still exists as part of the Leyland DAF group. The archives of Albion motors can still be found in Biggar.

In the summer of 1940 several thousands of Polish soldiers were stationed here, having been evacuated after the collapse of France. The singer Richard Tauber, whose wife Diana Napier was working with the Polish Red Cross, put on a special performance of the operetta The Land of Smiles during a two-week run in Glasgow. Later the Polish soldiers moved to the east coast of Scotland to defend the coast and to train for their deployment as the 1st Polish Armoured Division in Normandy, Belgium and the Netherlands.[4]

The fictional Midculter, which features in Dorothy Dunnett's Lymond Chronicles novels, is set here.

Features

editThe town was once served by the Symington, Biggar and Broughton Railway, which ran from the Caledonian Railway (now the West Coast Main Line) at Symington to join the Peebles Railway at Peebles. The station and signal box are still standing but housing has been built on the line running west from the station and the railway running east from the station is a public footpath to Broughton, part of the Biggar Country Path network.

This town has two schools, one primary, and one secondary. The secondary school, Biggar High School, also admits pupils from surrounding small towns and villages. Biggar Primary is a small school, located on South Back Road, with a current roll of 238 pupils. The High School, located on John's Loan and adjacent to the primary, shares its sports facilities with the primary school when the occasion demands it. The annual primary Sports Day is held on the High School playing field.

In 2007 local estate agent John Riley, encouraged a group of Biggar residents to launch the Carbon Neutral Biggar project, with the stated aim of becoming the first carbon neutral town in Scotland.[5] The launch of the project, covered in both local and national media, took place at the town's annual eco forum in May 2007. The group has formed links with the town of Ashton Hayes in Cheshire, which has a similar group working toward carbon neutral status for the town.

Attractions

editThe new Biggar & Upper Clydesdale Museum run by the Biggar Museum Trust opened in 2015 and the Biggar Gasworks Museum is the only preserved gas works in Scotland. Additionally, Biggar has Scotland's only permanent puppet theatre, Biggar Puppet Theatre, which is run by the Purves Puppets family. Biggar Corn Exchange, now also used as a theatre, was completed in 1861.[6]

Ian Hamilton Finlay's home and garden at Little Sparta is nearby in the Pentland Hills. The town hosts an annual arts festival, the Biggar Little Festival. The town has traditionally held a huge bonfire at Hogmanay.[7]

Notable people

editBiggar was the birthplace of Thomas Gladstones, the grandfather of William Ewart Gladstone. Hugh MacDiarmid spent his later years at Brownsbank, near the town.

- John Brown (1810–1882), physician and essayist – was born in a house in the South Back Road in 1810 which was at that time a manse. He is commemorated with a plaque on the front wall of the municipal hall.

- John Pairman (1788–1843), artist – lived in Biggar and is buried in the parish churchyard.[8]

- Prof Thomas Purdie (1843–1916), chemist

- Erich Schaedler (1949–1985), footballer

- Alice Maud Shipley (1869–1951), lady's maid to Mrs Margaret Pairman and militant suffragette – buried in the parish churchyard

Geography

editThe town of Biggar is 200 metres (660 ft) above sea level.

Climate

editBiggar has an oceanic climate (Köppen: Cfb). Camps Reservoir is a nearby weather station situated at an elevation of 295 m (968 ft).

| Climate data for Camps Reservoir, Elevation: 295 m (968 ft), 1991–2020 normals | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Mean daily maximum °C (°F) | 5.0 (41.0) |

5.4 (41.7) |

7.2 (45.0) |

10.0 (50.0) |

13.4 (56.1) |

15.7 (60.3) |

17.2 (63.0) |

16.8 (62.2) |

14.5 (58.1) |

11.0 (51.8) |

7.5 (45.5) |

5.4 (41.7) |

10.8 (51.4) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 2.3 (36.1) |

2.4 (36.3) |

3.8 (38.8) |

5.9 (42.6) |

8.9 (48.0) |

11.5 (52.7) |

13.2 (55.8) |

12.9 (55.2) |

10.6 (51.1) |

7.6 (45.7) |

4.6 (40.3) |

2.5 (36.5) |

7.2 (44.9) |

| Mean daily minimum °C (°F) | −0.4 (31.3) |

−0.7 (30.7) |

0.4 (32.7) |

1.7 (35.1) |

4.4 (39.9) |

7.4 (45.3) |

9.1 (48.4) |

9.0 (48.2) |

6.8 (44.2) |

4.2 (39.6) |

1.7 (35.1) |

−0.3 (31.5) |

3.6 (38.5) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 152.8 (6.02) |

124.8 (4.91) |

101.6 (4.00) |

76.5 (3.01) |

76.4 (3.01) |

77.3 (3.04) |

92.3 (3.63) |

108.1 (4.26) |

100.8 (3.97) |

146.2 (5.76) |

147.4 (5.80) |

149.1 (5.87) |

1,353.3 (53.28) |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 35.9 | 57.3 | 89.6 | 130.0 | 180.3 | 142.4 | 133.6 | 132.9 | 107.8 | 69.3 | 40.9 | 30.8 | 1,150.4 |

| Source: Met Office[9] | |||||||||||||

See also

editReferences

edit- ^ "Mid-2020 Population Estimates for Settlements and Localities in Scotland". National Records of Scotland. 31 March 2022. Retrieved 31 March 2022.

- ^ "Bigear". faclair.com. Retrieved 19 October 2018.

- ^ a b Matheson, Ann (1998). Old Biggar. Catrine, Ayrshire: Stenlake Publishing. p. 3. ISBN 9781840335743. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 17 April 2013.

- ^ "Polonica Biggar". Ostrycharz.free-online.co.uk. Retrieved 14 November 2012.

- ^ Carbon Neutral Biggar Archived 19 May 2007 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Historic Environment Scotland. "Biggar Corn Exchange, High Street (LB22240)". Retrieved 14 October 2023.

- ^ "BIGGAR BONFIRE 2021 website sponsored by ANDREW WILSON – Freelance Photographer".

- ^ "Biggar and the House of Fleming".

- ^ "Camps Reservoir Climate". Met Office. Retrieved 5 April 2024.

External links

edit- Media related to Biggar, South Lanarkshire at Wikimedia Commons