Lamont Coleman (May 30, 1974 – February 15, 1999), known professionally as Big L, was an American rapper, songwriter, and record producer.[1] Emerging from Harlem in New York City in 1992, Big L became known among underground hip-hop fans for his freestyling ability. He was eventually signed to Columbia Records, where, in 1995, he released his debut album, Lifestylez ov da Poor & Dangerous. On February 15, 1999, he was fatally shot nine times in a drive-by shooting in Harlem.

Big L | |

|---|---|

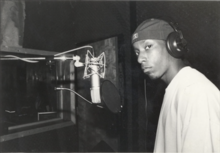

Big L in 1998 | |

| Background information | |

| Birth name | Lamont Coleman |

| Also known as | L Corleone |

| Born | May 30, 1974 New York City, U.S. |

| Died | February 15, 1999 (aged 24) New York City, U.S. |

| Genres | East Coast hip hop |

| Occupations |

|

| Years active | 1992–1999 |

| Labels | |

Big L was noted for his use of wordplay, and writers at AllMusic, HipHopDX and The Source have praised him for his lyrical ability.[2][3] Henry Adaso described him as "one of the most talented poets in hip-hop history."[4]

In an interview with Funkmaster Flex, Nas claimed Big L "scared me to death. When I heard [his performance at the Apollo Theater] on tape, I was scared to death. I said, 'Yo, it's no way I can compete if this is what I gotta compete with.'"[5]

Early life

editColeman was born on May 30, 1974, in the Harlem neighborhood of New York City.[6] He was the third and youngest child of Gilda Terry (d. 2008)[7] and Charles Davis.[8] Davis left the family while Coleman was a child.[9] He had two older half siblings: Donald and Leroy Phinazee (d. 2002).[7][8] Coleman received the nicknames "Little L" and "Mont-Mont" as a child.[10][11] His elder brother, Donald Phinazee, took Coleman to a Run-DMC concert at the Beacon Theatre when Coleman was about 7 years old. According to Phinazee, Coleman was awed by the performance which sparked his interest in rapping. By age 12, Coleman became a big hip hop fan and started freestyling with other people in his neighborhood.[8][11]

Coleman began writing rhymes in 1990.[8] He also founded a group known as Three the Hard Way in 1990, but it was quickly broken up due to a lack of enthusiasm among the members which consisted of Coleman, Doc Reem, and Rodney.[12][13] No projects were released, and after Rodney left, the group was renamed Two Hard Motherfuckers.[12] Around this time, people started to refer to Coleman as "Big L".[8] In the summer of 1990, Coleman met Lord Finesse at an autograph session in a record shop on 125th Street.[14][15] After he did a freestyle, Finesse and Coleman exchanged numbers.[15]

Coleman attended Julia Richman High School and graduated in 1992.[8] While in high school, Coleman freestyle battled regularly; in his last interview, he stated, "in the beginning, all I ever saw me doing was battling everybody on the street corners, rhyming in the hallways, beating on the wall, rhyming to my friends. Every now and then, a house party, grab the mic, a block party, grab the mic."[16]

Career

edit1992–1995: First recordings and record deal

editIn 1992, Coleman recorded various demos, some of which were featured on his debut album Lifestylez ov da Poor & Dangerous.[13][17] On February 11, Coleman appeared on Yo! MTV Raps with Lord Finesse to help promote Finesse's studio album Return of the Funky Man.[8] Coleman's first professional appearance came on "Yes You May (Remix)", the B-side of "Party Over Here" (1992) by Lord Finesse,[17] and his first album appearance was on "Represent" off of Showbiz & A.G.'s Runaway Slave (1992).[14]

During this time, he won an amateur freestyle battle hosted by Nubian Productions which consisted of about 2,000 contestants.[18] In 1993, Coleman signed to Columbia Records.[13] He then joined Lord Finesse's Bronx-based hip hop collective Diggin' in the Crates Crew (DITC) which consisted of Lord Finesse, Diamond D, O.C., Fat Joe, Buckwild, Showbiz and A.G. In 1993, Coleman released his first promotional single, "Devil's Son", and later said it was one of the first horrorcore singles, influencing others. He said he wrote the song because "I've always been a fan of horror flicks. Plus the things I see in Harlem are very scary. So I just put it all together in a rhyme." However, he said he preferred other styles over horrorcore.[14]

Coleman founded the Harlem rap group Children of the Corn (COC) with Killa Cam (Cam'ron), Murda Mase (Ma$e), Bloodshed and McGruff in 1993. On February 18, 1993, he performed live at the Uptown Lord Finesse Birthday Bash at the 2,000 Club, which included other performances from Fat Joe, Nas, and Diamond D.[8] In 1994, he released his second promotional single "I Shoulda Used a Rubba" ("Clinic"). On July 11, 1994, Coleman released the radio edit of "Put It On", followed up by the release of the music video three months later.[8] In 1995, the music video for the single "No Endz, No Skinz" debuted. It was directed by Brian Luvar.[19]

His debut studio album, Lifestylez ov da Poor & Dangerous, was released in March 1995. The album debuted at number 149 on the Billboard 200[20] and number 22 on Top R&B/Hip-Hop Albums.[21] Lifestylez would go on to sell over 200,000 copies as of 2000.[22] Three singles were released from the album; the first two, "Put It On" and "M.V.P.", reached the top 25 of Billboard's Hot Rap Tracks and the third "No Endz, No Skinz" did not chart.[23][24]

1996–1999: independent release

editIn 1996, Big L was dropped from Columbia mainly because of a dispute with the label over artistic differences.[25][26] He stated, "I was there with a bunch of strangers that didn't really know my music."[27]

In 1997, he started working on his second studio album, The Big Picture.[28] COC folded when Bloodshed died in a car accident in New York on March 2, 1997.[29] Later that year, DITC appeared in the July issue of On The Go Magazine.[8] Coleman then appeared on O.C.'s single "Dangerous" from O.C.'s second album Jewelz.[30] That November, he was the opening act for O.C.'s European Jewlez Tour.[8]

In 1998, Big L formed his own independent label, Flamboyant Entertainment.[31] According to The Village Voice, it "planned to distribute the kind of hip-hop that sold without top 40 samples or R & B hooks."[32] That same year, Coleman released the single "Ebonics".[33] The song, based on African-American Vernacular English, was called one of the top five independent singles of the year by The Source.[15] In May 1998, DITC released their first single, "Dignified Soldiers".[6] That September, Big L was featured in XXL's iconic A Great Day in Hip Hop photograph, a replica of A Great Day in Harlem.

Following the release of "Ebonics", Big L caught the eye of Damon Dash, the CEO of Roc-A-Fella Records. Dash offered to sign him to Roc-A-Fella, but Big L wanted his crew to sign as well.[34][35] On February 8, 1999, Coleman, Herb McGruff, C-Town, and Jay-Z started the process to sign with Roc-A-Fella as a group called "The Wolfpack".[8][36]

Murder and aftermath

editOn February 15, 1999, Coleman was killed in a drive-by shooting at 45 West 139th Street in his native Harlem. He was hit nine times in the face and chest.[37][38] Gerard Woodley, one of Coleman's childhood friends, was arrested three months later for the crime.[39] "It's a good possibility it was retaliation for something Big L's brother did, or Woodley believed he had done," said a spokesperson for the New York City Police Department.[40] Woodley was later released due to lack of evidence, and the murder case remains officially unsolved.[41]

Woodley was fatally shot in the head on June 24, 2016.[42][43] Woodley's family maintains his innocence in Coleman's killing.[44] Rapper Cam'ron, who was a close friend of Coleman and Woodley, posted a video to Instagram claiming Coleman had attempted to murder Woodley a week before his death.[45][46]

In 2017, Lou Black, Gerard Woodley's cousin, published Ethylene: The Rise and Fall of The 139th St. NFL Crew. The book details Black's first hand interactions with the NFL crew and Big L. In the book, Black claims Leroy "Big Lee" Phinazee, Coleman's eldest half-brother and leader of the NFL crew, violated his probation when he was found to be in possession of an illegal weapon and was sentenced to prison. According to Black, while in prison, Phinazee met and contracted a hitman from Brooklyn to murder three members of the NFL gang including Woodley. Phinazee had tasked Big L to identify the targets to the hitman. On the day when the murder was planned, Woodley noticed the hitman following him and successfully scared him off. As Big L had been seen multiple times with the alleged hitman days prior, Woodley assumed Big L had taken part in the attempted shooting. Approximately a week after the attempted shooting of Woodley, Big L was killed. Black did not specify if Woodley personally killed Big L.[47]

Big L is buried at George Washington Memorial Park in Paramus, New Jersey.[48]

Posthumous releases

editThe tracks "Get Yours", "Way of Life", and "Shyheim's Manchild" b/w "Furious Anger" were released as singles in 1999 for DITC's self-titled album (2000) on Tommy Boy Records.[8][49] The album peaked at number 31 on R&B/Hip-Hop Albums and number 141 on the Billboard 200.[50] Coleman's first posthumous single was "Flamboyant" b/w "On the Mic", which arrived on May 30, 2000.[51] The single peaked at number 39 on the Billboard Hot R&B/Hip-Hop Songs[52] and topped the Hot Rap Tracks,[24] making it Coleman's first and only number-one single.

Coleman's second and final studio album, The Big Picture, was released on August 1, 2000, and featured Fat Joe, Tupac Shakur, Guru of Gang Starr, Kool G Rap, and Big Daddy Kane among others. The Big Picture was put together by his manager and partner in Flamboyant Entertainment, Rich King. It contains songs that he had recorded and a cappella recordings that were never used, completed by producers and guest emcees that Coleman respected or had worked with previously.[8]

The Big Picture debuted at number 13 on the Billboard 200, number two on Top R&B/Hip-Hop Albums, and sold 72,549 copies.[22] The album was certified gold a month later for shipments of 500,000 copies by the RIAA.[53] The Big Picture was the only music by Big L to appear on a music chart outside of the United States, peaking at number 122 on the UK Albums Chart.[54]

Children of the Corn: The Collector's Edition, a compilation album containing COC songs, was released in 2003. Big L's next posthumous album, 139 & Lenox, was released on August 31, 2010.[55] Issued by Rich King on Flamboyant Entertainment, it contained previously unreleased and rare tracks.[55][56] The follow-up album, Return of the Devil's Son (2010), peaked at number 73 on R&B/Hip-Hop Albums.[57] Coleman's next release was The Danger Zone (2011).[58]

Legacy and influence

editHenry Adaso, a music journalist for About.com, called him the 23rd-best MC of 1987 to 2007, claiming "[he was] one of the most auspicious storytellers in hip hop history."[4] HipHopDX called Coleman "the most underrated lyricist ever".[13] Many tributes have been given to Coleman. The first was by Lord Finesse and the other members of DITC on March 6, 1999, at the Tramps.[8] The Source has done multiple tributes to him: first in July 2000,[59] and then in March 2002.[60] XXL also did a tribute to Coleman in March 2003.[61] On February 16, 2005, at SOB's restaurant and nightclub in Manhattan, a commemoration was held for him.[62] It included special guests such as DITC, Herb McGruff, and Kid Capri.[62] All the money earned went to his estate.[62]

In 2004, Eminem paid tribute to Coleman in the music video for his single "Like Toy Soldiers". In an interview with MTV, Jay-Z stated: "We were about to sign him right before he passed away. We were about to sign him to Roc-a-Fella. It was a done deal…I think he was very talented…I think he had the ability to write big records, and big choruses."[5] Rapper Nas also said on MTV, "He scared me to death. When I heard that on tape, I was scared to death. I said, 'Yo, it's no way I can compete if this is what I gotta compete with.'"[5]

In 2017, Royce da 5'9" said he believed Coleman would have been a "top 3" rapper all time if he had not been killed so prematurely.[63] In 2019, Funkmaster Flex said "People can get mad at me for saying this, but he was the best lyricist at the time. He was a better lyricist than Biggie and Jay-Z. He just didn't have the marketing and promotion. Let me go on the record and say that. It's the truth."[64] In 2022, the 140th Street and Lennox Avenue intersection in Harlem was co-named Lamont "Big L" Coleman Way.[65]

Style

editColeman is often credited in helping to create the horrorcore genre of hip hop with his 1992 song "Devil's Son."[14] However, not all his songs fall into this genre. For example, in the song "Street Struck," Coleman discusses the difficulties of growing up in the ghetto and describes the consequences of living a life of crime.[citation needed] Idris Goodwin of The Boston Globe wrote that "[Big L had an] impressive command of the English language", with his song "Ebonics" being the best example of this.[66]

Coleman was notable for using a rap style called "compounding".[67] He also used metaphors in his rhymes.[68] M.F. DiBella of Allmusic stated Coleman was "a master of the lyrical stickup undressing his competition with kinetic metaphors and a brash comedic repertoire".[68] On the review of The Big Picture, she adds, describing "the Harlem MC as a master of the punch line and a vicious storyteller with a razor blade-under-the-tongue flow."[26] Trent Fitzgerald of Allmusic said Coleman was "a lyrically ferocious MC with raps deadlier than a snakebite and mannerisms cooler than the uptown pimp he claimed to be on records."[69]

Documentary

editA documentary Street Struck: The Big L Story was set to be released in 2017. Directed by a childhood friend and independent film director, Jewlz,[18] approximately nine hours of footage was brought in, and the film's planned runtime was said to be 90 to 120 minutes long.[34] Released on August 29, 2009,[18] the first trailer detailed that Street Struck would contain interviews from his mother Gilda Terry; his brother Donald; childhood friends E-Cash, D.O.C., McGruff, and Stan Spit; artists Mysonne and Doug E. Fresh; producers Showbiz and Premier; and recording DJs Cipha Sounds and Peter Rosenberg.[18] Put together by Coleman's brother Donald, a soundtrack was said to have been made for the documentary as well.[34] As of 2024, both the documentary and soundtrack have yet to be released.

Discography

edit- Studio album

- Posthumous albums

- The Big Picture (2000)

- 139 & Lenox (2010)

- Return of the Devil's Son (2010)

- The Danger Zone (2011)

See also

editReferences

edit- ^ "Today in hip hop history: Big L was shot and killed 22 years ago". The Source. February 15, 2021. Archived from the original on June 12, 2021. Retrieved June 17, 2021.

- ^ "The Source: Top 50 Lyricists [Magazine Scans]". Genius. Archived from the original on September 12, 2015. Retrieved April 8, 2019.

- ^ Henry Adaso. "10 Great Rappers Who Died Too Young". About.com Entertainment. Archived from the original on December 5, 2016. Retrieved May 1, 2018.

- ^ a b Adaso, Henry. 50 Greatest MCs of Our Time (1987–2007) Archived April 5, 2015, at the Wayback Machine. About.com. Retrieved August 27, 2011

- ^ a b c Fleischer, Adam. "Big L Would Have Been 40 Today: Here's How He Impacted Jay Z, Mac Miller And More". MTV News. Archived from the original on August 31, 2014. Retrieved April 8, 2019.

- ^ a b "Big L > Overview". Allmusic. Archived from the original on September 3, 2011. Retrieved November 5, 2011.

- ^ a b Paine, Jake (February 18, 2008). "Big L's Mother Passes Away". HipHop DX. Cheri Media Group. Archived from the original on June 28, 2011. Retrieved November 6, 2011.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o The Big Sleep (November 7, 2008). "Lamont 'Big L' Coleman Timeline". Big L Online. Archived from the original on May 2, 2012. Retrieved September 28, 2011.

- ^ Arnold, Paul (July 12, 2012). "Lord Finesse Says There Will 'Never' Be Another Big L Album". HipHop DX. Cheri Media Group. Archived from the original on January 21, 2012. Retrieved February 9, 2012.

- ^ Ovalle, David (December 2, 2002). "Rapper, 23, Was on the Verge of Stardom When He Was Gunned Down in Harlem". The Miami Herald. p. 1E.

- ^ a b Johnson, Brett (November 29, 2010). "Donald Phinazee on the life of Big L". Crave Online. Archived from the original on September 26, 2011. Retrieved September 21, 2011.

- ^ a b Soobax (November 20, 2009). "Donald Phinazee's Q&A – Part Two!". Big L Online. Archived from the original on January 18, 2013.

- ^ a b c d Udoh, Meka (February 15, 2007). "Remembering Lamont 'Big L' Coleman". HipHop DX. Archived from the original on December 15, 2011. Retrieved September 29, 2011.

- ^ a b c d Daniel, Jamila (April 1995). "Uptown Renaissance: Big L". The Source (67): 36. ISSN 1063-2085.

- ^ a b c "Big L: Bio". Rawkus Records. Archived from the original on March 31, 2001.

- ^ Coleman, Lamont (1998). "Big L's last interview (Oxygen FM in Amsterdam '98)". Oxygen FM (Interview). Amsterdam.

- ^ a b Hess (2010), p. 40

- ^ a b c d BigLOnline (August 29, 2009). "Big L Documentary Trailer (First Draft) – 'Street Struck: The Big L Story.' Coming Soon!". YouTube. Archived from the original on July 5, 2011. Retrieved October 27, 2011.

- ^ "No Endz, No Skinz – Big L". Vevo. Archived from the original on December 7, 2017. Retrieved November 7, 2011.

- ^ "Billboard 200". Billboard. Vol. 107, no. 15. Nielsen Business Media. April 15, 1995. p. 78. ISSN 0006-2510. Archived from the original on September 6, 2023. Retrieved October 14, 2016.

- ^ "Billboard Top R&B Albums". Billboard. Vol. 107, no. 15. Nielsen Business Media. April 15, 1995. p. 22. ISSN 0006-2510. Archived from the original on September 6, 2023. Retrieved October 14, 2016.

- ^ a b Berry, Jahna (August 11, 2000). "Street Buzz, Duets Fuel Sales of Big L's The Big Picture". Vh1. MTV Networks. Archived from the original on October 12, 2011. Retrieved October 30, 2011.

- ^ Krishnamurthy, Sowmya (February 15, 2012). "Hip-Hop Remembers Big L on the Anniversary of His Death". MTV.com. MTV Networks. Archived from the original on February 18, 2012. Retrieved February 19, 2012.

- ^ a b Big L > Charts & Awards > Billboard Singles. AllMusic. Retrieved September 10, 2011.

- ^ "Big L Remembered: The 10 Best Verses From 'The Big Picture'". theboombox.com. February 15, 2017. Archived from the original on January 18, 2023. Retrieved January 18, 2023.

- ^ a b DiBella, M.F. "The Big Picture – Big L > Review". AllMusic. Archived from the original on March 31, 2012. Retrieved October 31, 2011.

- ^ Lewis, Mike (1998). "The Crate & The Good". Hip Hop Connection. ISSN 1465-4407.

- ^ Salaam, Ismael (February 15, 2009). "Rapper Big L Remembered 10 Years Later". AllHipHop.com. Archived from the original on August 10, 2013. Retrieved February 11, 2012.

- ^ "TODAY IN HIP-HOP: RIP BLOODSHED". XXL. March 2, 2015. Retrieved August 3, 2016.

- ^ "Dangerous: O.C." AllMusic. Archived from the original on August 22, 2024. Retrieved November 9, 2011.

- ^ Park, April (September 13, 2000). "Big L: The Big Picture (Rawkus/Flamboyant)". Riverfront Times. Archived from the original on August 10, 2013. Retrieved February 5, 2012.

- ^ Jasper (1999), p. 2

- ^ Berry, Jahna (July 31, 2000). "Big L's Second Album Due, More Than A Year After His Death". Vh1. Viacom. Archived from the original on May 13, 2014.

- ^ a b c Donald Phinazee (November 10, 2009). "Big L's Brother Talks His Death and the New Album". Vimeo (Interview). Interviewed by Bill Starlin. Archived from the original on March 8, 2021. Retrieved November 10, 2011.

- ^ Hess (2010), p. 41

- ^ Herb McGruff (July 25, 2010). "Herb McGruff Jay Z & Big L Deal". YouTube (Interview). Interviewed by Mikey T. Archived from the original on March 11, 2016. Retrieved November 25, 2016.

- ^ Romano, Will (May 3, 2000). "Slain Rapper Big L's Posthumous Album Due". Vh1. Viacom. Archived from the original on December 26, 2019. Retrieved February 8, 2012.

- ^ "Violence and Hip Hop". BBC News. October 31, 2002. Archived from the original on February 23, 2012. Retrieved November 2, 2011.

- ^ "Suspect Arrested in Big L Shooting". MTV.com. MTV Networks. May 21, 1999. Archived from the original on April 29, 2011. Retrieved November 2, 2011.

- ^ "Arrest Made in Big L Case". Rolling Stone. May 17, 1999. Archived from the original on March 21, 2009.

- ^ Gray, Madison (September 13, 2011). "Big L – Top 10 Unsolved Hip-Hop Murders". Time. Archived from the original on September 23, 2011. Retrieved November 13, 2011.

- ^ Sommerfeldt, Chris. "Man suspected of killing hip-hop star Big L in 1999 shot, killed in Harlem; one of two men gunned down Thursday". New York Daily News. Archived from the original on May 18, 2020. Retrieved August 2, 2016.

- ^ Clark, Trent (June 25, 2016). "Big L's Alleged Killer Murdered In Harlem". HipHopDX. Archived from the original on October 23, 2016. Retrieved November 9, 2016.

- ^ "Big l'S Alleged Killer Murdered in Harlem". June 25, 2016.

- ^ Mazariego, Omar (July 26, 2016). "Cam'Ron Hints At The Story Behind Big L's Murder In New Verse". The Latest Hip-Hop News, Music and Media | Hip-Hop Wired. Archived from the original on September 3, 2022. Retrieved September 3, 2022.

- ^ ESPINOZA, JOSHUA (July 26, 2016). "Cam'ron Drops a New Verse About Big L and His Suspected Murderer". Complex. Archived from the original on September 3, 2022. Retrieved September 3, 2022.

- ^ Black, Lou (June 19, 2017). Ethylene: The Rise and Fall of The 139th St. NFL Crew (1st ed.). Respect the Pen LLC. pp. 147–152. ISBN 978-0-9989986-0-2.

- ^ "Harlem World Magazine". Archived from the original on April 20, 2023. Retrieved May 20, 2019.

- ^ "D.I.T.C. – D.I.T.C. > Overview". AllMusic. Archived from the original on August 22, 2024. Retrieved November 2, 2011.

- ^ "D.I.T.C. – D.I.T.C. > Charts @ Awards > Billboard Albums". AllMusic. Archived from the original on August 22, 2024. Retrieved November 5, 2011.

- ^ Gill, John (May 3, 2000). "Big L's First Posthumous Single Arrives". MTV.com. MTV Networks. Archived from the original on February 9, 2012. Retrieved November 5, 2011.

- ^ "Hot R&B/Hip-Hop Songs". Billboard. Prometheus Global Media. September 16, 2000. Archived from the original (XML) on April 22, 2012. Retrieved November 7, 2011.

- ^ "American album certifications – Big L – The Big Picture". Recording Industry Association of America. October 11, 2000. Retrieved September 29, 2011.

- ^ Zywietz, Tobias (May 7, 2011). "Chart Log UK: Darren B – David Byrne". Zobbel.de. Archived from the original on August 13, 2007. Retrieved April 8, 2012.

- ^ a b Hanna, Mitchell (August 3, 2010). "Tuesday Rap Release Dates: Kanye West, Big L, Gucci Mane, Black Milk". HipHop DX. Cheri Media Group. Archived from the original on February 12, 2011. Retrieved November 11, 2011.

- ^ "139 & Lenox > Overview". AllMusic. Archived from the original on October 24, 2010. Retrieved November 21, 2011.

- ^ "Charts & Awards: Big L". AllMusic. Archived from the original on August 22, 2024. Retrieved April 29, 2011.

- ^ Vasquez, Andres (June 3, 2011). "Big L – The Danger Zone". HipHop DX. Cheri Media Group. Archived from the original on June 8, 2011. Retrieved June 5, 2011.

- ^ Rodriquez, Carlito (July 2000). "The Tragic Story of an 11 Year Old Killer, Our Tribute to Big L". The Source (130). ISSN 1063-2085.

- ^ Rodriquez, Carlito (March 2002). "The Greatest MC, Albums and Moments". The Source (150): 118. ISSN 1063-2085.

- ^ "Big L, Book of Rhymes, Vol. 2". XXL. 7 (45). Harris Publications. March 2003.

- ^ a b c "Commemorating the Life of the Legendary 'Big L'". SOB's. Archived from the original on February 4, 2005.

- ^ "The Source |Royce da' 5'9" Believes That Big L "was better than Jay Z"". May 10, 2017. Archived from the original on October 26, 2021. Retrieved October 26, 2021.

- ^ ""Flamboyant:" How Rap Legends Remember Big L 20 Years After His Death". March 28, 2019. Archived from the original on August 22, 2024. Retrieved October 26, 2021.

- ^ "Big L, Forever". June 2022. Archived from the original on August 22, 2024. Retrieved June 13, 2022.

- ^ Goodwin, Idris (December 7, 2010). "Anthology Expands Rap from Music to Literature". The Boston Globe. New York Times Company. Archived from the original on January 18, 2013. Retrieved February 9, 2012.

- ^ Herb McGruff (April 26, 2009). "The Herb McGruff Interview". Big L Online (Interview). Interviewed by Francesca Djerejian. Archived from the original on May 2, 2012.

- ^ a b DiBella, M.F. "Lifestylez ov da Poor and Dangerous – Big L > Review". AllMusic. Archived from the original on November 10, 2011. Retrieved October 31, 2011.

- ^ Fitzgerald, Trent. "D.I.T.C. > Biography". AllMusic. Archived from the original on August 22, 2024. Retrieved November 8, 2011.

Sources

edit- Hess, Mickey (2010). Hip Hop in America: A Regional Guide: Volume 1: East Coast and West Coast. ABC-CLIO. ISBN 978-0-313-34323-0.

- Jasper, Kenji (July 6, 1999). "Of Mics and Men in Harlem". The Village Voice. Archived from the original on August 10, 2013. Retrieved February 6, 2012.

External links

edit- Official website (archived)

- Big L at AllMusic