This article needs additional citations for verification. (February 2013) |

The Battle of Edgehill (or Edge Hill) was a pitched battle of the First English Civil War. It was fought near Edge Hill and Kineton in southern Warwickshire on Sunday, 23 October 1642.

| Battle of Edgehill | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the First English Civil War | |||||||

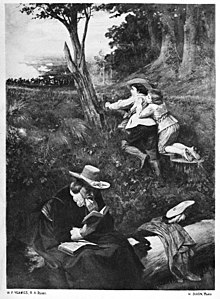

The Prince of Wales and the Duke of York sheltering during the Battle of Edgehill | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| Royalists | Parliamentarians | ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

Earl of Essex Lord Feilding | |||||||

| Strength | |||||||

|

| ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

|

500 killed 1,500 wounded |

500 killed 1,500 wounded[2] | ||||||

Warwickshire | |||||||

All attempts at constitutional compromise between King Charles and Parliament broke down early in 1642. Both the King and Parliament raised large armies to gain their way by force of arms. In October, at his temporary base near Shrewsbury, the King decided to march to London in order to force a decisive confrontation with Parliament's main army, commanded by the Earl of Essex.

Late on 22 October, both armies unexpectedly found the enemy to be close by. The next day, the Royalist army descended from Edge Hill to force battle. After the Parliamentarian artillery opened a cannonade, the Royalists attacked. Both armies consisted mostly of inexperienced and sometimes ill-equipped troops. Many men from both sides fled or fell out to loot enemy baggage, and neither army was able to gain a decisive advantage.

After the battle, the King resumed his march on London, but was not strong enough to overcome the defending militia before Essex's army could reinforce them. The inconclusive result of the Battle of Edgehill prevented either faction from gaining a quick victory in the war, which eventually lasted four years.

Background

editWhen it appeared to King Charles I that no agreement with Parliament over the government of the kingdom was possible, he left London on 2 March 1642 and headed for the north of England. Both Parliament and King realised that armed conflict was inevitable, and prepared to raise forces. Parliament enacted a Militia Ordinance, by which it claimed authority over the country's Trained Bands, while from his temporary capital of York, Charles rejected Parliament's Nineteen Propositions and issued Commissions of Array, directing the Lord Lieutenant of each county to raise forces for the King.

The King then attempted to seize the port of Kingston-upon-Hull where arms and equipment previously collected for the Bishops' Wars had been gathered. In the Siege of Hull, the Parliamentarian garrison defied the King's authority and drove his forces away from the city. In early August the King moved south, to Lincoln and Leicester, where he secured the contents of the local armouries. On 22 August, he took a decisive step by raising the royal standard in Nottingham, effectively declaring war on Parliament.

The Midlands were generally Parliamentarian in sympathy, and few people rallied to the King there, so having again secured the arms and equipment of the local trained bands, Charles moved to Chester and subsequently to Shrewsbury, where large numbers of recruits from Wales and the Welsh border were expected to join him. (By this time, there was conflict in almost every part of England, as local commanders attempted to seize the main cities, ports and castles for their respective factions.)

Having learned of the King's actions in Nottingham, Parliament dispatched its own army northward under the Earl of Essex, to confront the King. Essex marched first to Northampton, where he mustered almost 20,000 men. Learning of the King's move westwards, Essex then marched north-westwards towards Worcester. On 23 September, in the first clash between the main Royalist and Parliamentarian armies, Royalist cavalry under Prince Rupert of the Rhine routed the cavalry of Essex's vanguard at the Battle of Powick Bridge. Nevertheless, lacking infantry, the Royalists abandoned Worcester.

Prelude

editBy early October, the King's army was almost complete at Shrewsbury. He held a council of war, at which two courses of action were considered. The first was to attack Essex's army at Worcester, which had the drawback that the close country around the city would put the superior Royalist cavalry at a disadvantage.[3] The second course, which was adopted, was to advance towards London. The intention was not to avoid battle with Essex, but to force one at an advantage. In the Earl of Clarendon's words: "it was considered more counsellable to march towards London, it being morally sure that Essex would put himself in their way." Accordingly, the army left Shrewsbury on 12 October, gaining two days' start on the enemy, and moved south-east. Essex followed, but neither army had much information on the location of their enemy.

By 22 October, the Royalist army was quartered in the villages around Edgcote, and was threatening the Parliamentarian post at Banbury. The garrison of Banbury sent messengers pleading for help to the garrison of Warwick Castle. Essex, who had just reached there, ordered an immediate march to Kineton to bring relief to Banbury, even though his army had straggled and not all his troops were present. That evening, there were clashes between outposts and quartermasters' parties in Kineton and the villages nearby, and the Royalists had their first inkling that Essex's army was close by.[4] The King issued orders for his army to muster for battle on top of the escarpment of Edge Hill the following day.

Essex originally intended marching straight to the relief of Banbury, but at about 8 a.m. on 23 October, his outposts reported that the Cavaliers were massed on Edge Hill, 4.5 miles (7.2 km) from Kineton. Essex deployed his army about halfway between Kineton and the Royalist army, where hedges formed a natural position.

The well known "Soldiers' Prayer" was given by Jacob Astley before the battle.[a]

Opposing forces

editThere were some significant differences between the opposing armies, which were to be important to the course of the battle and its outcome. Although both armies were composed of very raw soldiers, they had several experienced officers who had previously fought in the Dutch or Swedish armies during the Thirty Years' War. Several of them had been recruited to lead English forces which were intended to be sent to Ireland following the Irish Rebellion of 1641. Both King and Parliament had bid highly for their services.

The Royalist cavalry was superior to Parliament's cavalry at this stage of the war. Oliver Cromwell, who possibly arrived late to the battle, later wrote disparagingly to John Hampden, "Your troopers are most of them old decayed servingmen and tapsters; and their [the Royalists] troopers are gentlemen's sons, younger sons and persons of quality...."[6] Not only were the Parliamentarian cavalry not so naturally accustomed to mounted action, but they were drilled in the Dutch tactic of firing pistols and carbines from the saddle, whereas under Rupert, the Royalist cavalry would charge sword in hand, relying on shock and weight.

The Parliamentarian foot soldiers, however, were better equipped than their Royalist counterparts. The Royalist pikemen were said to lack armour, and the musketeers lacked swords, making the Royalist infantry more vulnerable in hand-to-hand combat. Several hundred of them lacked any sort of weapon apart from clubs or improvised polearms.

Deployments

editRoyalist Army

editThe Royalist right wing of cavalry and dragoons was led by Prince Rupert, with Sir John Byron in support. The King's own Lifeguard of Horse insisted on joining Rupert's front line, leaving the King with no cavalry reserve under his own command.[7]

The centre consisted of five "tertias" of infantry. There was a last-minute change of command when the Colonel General, Lord Lindsey, was overruled when he wished to deploy them in "Dutch" formation, simple phalanxes eight ranks deep. Affronted, he resigned his command and took his place at the head of his own regiment of foot. He was replaced by the Lieutenant General, Patrick Ruthven, who drew up the infantry in chequerboard "Swedish" formation, which was potentially more effective but also more difficult to control, particularly with inexperienced soldiers.[b] The centre was led in battle by Sergeant Major General Jacob Astley.

The left wing consisted of horse under Sir Henry Wilmot, with Lord Digby, the King's secretary of state, in support and Colonel Arthur Aston's dragoons on his left flank.

Parliamentarians

editThe Parliamentarian left wing consisted of a loosely organised cavalry brigade of twenty unregimented troops under Sir James Ramsay, supported by 600 musketeers and several cannon, deployed behind a hedge.[9]

In the centre, the infantry brigade of Sir John Meldrum was drawn up on the left of the front line and Colonel Charles Essex's[c] brigade on the right. Sir Thomas Ballard's infantry brigade was deployed behind Meldrum and the cavalry regiments under Sir William Balfour and Sir Philip Stapleton behind Charles Essex.[9] The presence of these two regiments was to be important in the coming battle.

A regiment of infantry under Colonel William Fairfax linked the centre to the right wing. The right wing consisted of cavalry under Lord Feilding, posted on some rising ground, with two regiments of dragoons in support.[9]

Battle

editAs Essex showed no signs of wishing to attack, the Royalists began to descend the slope of Edge Hill some time after midday. Even when they had completed this manoeuvre at about two o'clock, the battle did not begin until the sight of the King with his large entourage riding from regiment to regiment to encourage his soldiers, apparently goaded the Parliamentarians into opening fire.[10]

The King's party withdrew out of range and an artillery duel started. The Royalist guns were not effective, as most of them were deployed some way up the slope; from this height most of their shots plunged harmlessly into the earth. While the bombardment continued however, the Royalist dragoons advanced on each flank and drove back the Parliamentarian dragoons and musketeers covering their wings of horse.

On the right flank, Rupert gave the order to attack. As his charge gathered momentum, a troop of Parliamentarian horse under Faithful Fortescue abruptly defected. The rest of Ramsay's brigade gave an ineffectual volley of pistol fire from the saddle before turning to flee. Rupert's and Byron's troopers rapidly overran the Parliamentarian guns and musketeers on this flank and galloped jubilantly in pursuit of Ramsay's men, to the detriment of the infantry.

Wilmot charged about the same time on the other flank. Feilding's outnumbered troops quickly gave way, and Wilmot and Digby also chased them to Kineton where the Royalist horse fell out to loot the Parliamentarian baggage. Sir Charles Lucas and Lord Grandison rallied about 200 men, but when they tried to charge the Parliamentarian rear, they were distracted by fugitives from Charles Essex's routed brigade.[11]

The Royalist infantry also advanced in the centre under Ruthven. Many of the Parliamentarian foot had already run away as their cavalry disappeared, and others fled as the infantry came to close quarters. The brigades of Sir Thomas Ballard and Sir John Meldrum nevertheless stood their ground. The Parliamentarian cavalry regiments of Stapleton and Balfour emerged through gaps in the line of Parliamentarian foot soldiers, and charged the Royalist infantry. With no Royalist cavalry to oppose them, they put many units to flight.

The King had left himself without any proper reserve. As his centre gave way, he ordered one of his officers to conduct his sons Charles (the Prince of Wales) and James (the Duke of York) to safety while Ruthven rallied his infantry. Some of Balfour's men charged so far into the Royalist position that they menaced the princes' escort and briefly overran the Royalist artillery before withdrawing.[12] In the front ranks, Lord Lindsey was mortally wounded, and Sir Edmund Verney died defending the Royal Standard, which was captured by Parliamentarian Ensign Arthur Young. By this time, some of the Royalist horse had rallied and were returning from Kineton. Lieutenant Colonel Robert Welch (variously spelled Welch, Welsh, or Walsh)[d] of Wilmot's Horse recaptured the Royal Standard by a subterfuge as it was being taken to the Parliamentarian rear as a trophy.

Welch also captured two Parliamentarian cannon. As the light began to fade, the battle ended with a fire fight from either side of a dividing ditch, before nightfall eventually brought a natural close to hostilities. The Royalists had been forced back to the position they had originally advanced from, but had regrouped.

Outcome

editBy the following morning the King and his army returned to the Edge Hill escarpment and Essex's army returned to Kineton. It was a bitterly cold night with a hard frost. This was suggested by contemporary reports as the reason many of the wounded survived, since the cold allowed many wounds to congeal, saving the wounded from bleeding to death or succumbing to infection.

The following day, both armies partially formed up again, but neither was willing to resume the battle. Charles sent a herald to Essex with a message of pardon if he would agree to the King's terms, but the messenger was roughly handled and forced to return without delivering his message. Although Essex had been reinforced by some of his units which had lagged behind on the march, he withdrew during the evening and the majority of his army marched to Warwick Castle, abandoning seven guns on the battlefield.

In the early hours of Tuesday 25th, Prince Rupert led a strong detachment of horse and dragoons and launched a surprise attack upon what remained of the Parliamentarian baggage train at Kineton and killed many of the battle's wounded survivors discovered within the village.

Essex's decision to return northwards to Warwick allowed the King to continue southwards in the direction of London. Rupert urged this course, and was prepared to undertake it with his cavalry alone. With Essex's army still intact, the King chose to move more deliberately, with the whole army. After capturing Banbury on 27 October, he advanced via Oxford, Aylesbury and Reading. Essex meanwhile had moved directly to London. Reinforced by the London Trained Bands and many citizen volunteers, his army proved to be too strong for the King to contemplate another battle when the Royalists advanced to Turnham Green. The King withdrew to Oxford, which he made his capital for the rest of the war. With both sides almost evenly matched, it would drag on ruinously for years.

It is generally acknowledged that the Royalist cavalry's lack of discipline prevented a clear Royalist victory at Edge Hill. Not for the last time in the war, they would gallop after fleeing enemy and then break ranks to plunder, rather than rally to attack the enemy infantry. Byron's and Digby's men in particular, were not involved in the first clashes and should have been kept in hand rather than allowed to gallop off the battlefield. Patrick Ruthven was elevated to the rank of Lord General of the King's Army, confirming his role as acting commander in the battle.[14]

On the Parliamentarian side, Sir James Ramsay who had commanded the left wing horse which had been routed during the battle, was tried by court-martial at St. Albans on 5 November. The court reported that he had done all that it became a gallant man to do.

The last survivor of the battle, William Hiseland, fought also at Malplaquet sixty-seven years later.[15]

The Welch medal

editLieutenant Colonel Robert Welch, who had recaptured the royal standard, was knighted banneret on the field by King Charles I next morning. The King also granted a patent for a gold medal to be made (the first to be awarded to an individual for action on a battlefield) commemorating the event in Welch's honour. Captain John Smith also claimed a supporting part in the rescue of the royal standard and was accordingly also knighted banneret, but the medal was minted in Sir Robert Welch's name and honour.[16][17][18]

When in exile with Prince Charles, Welch committed a grave error of etiquette defending Prince Rupert.[19] Coupled with his friend Prince Rupert's political unpopularity among the Royalist exiles and the fact that Welch was an Irishman, Welch's part at Edge Hill was afterwards denigrated to the benefit of Smith (an Englishman) who was thus erroneously[citation needed] perpetuated as the hero in subsequent historical publications.[e]

Notes

edit- ^ "O Lord, Thou Knowest how busy I must be this day. If I forget Thee, do not Thou forget me."[5]

- ^ For the Earl of Forth as commander on the day rather than Rupert or the king see Murdoch and Grosjean.[8]

- ^ Not to be confused with the Parliamentary commander, whose name was Robert Devereux.

- ^ Royal warrants were written for several medals, including the 'Forlorn Hope' medal, and the medals awarded to Capt. John Smith and Sir Robert Welch (or Welsh, Walsh).[13]

- ^ In a traditional account, "Captain Smith, a Catholic officer of the King's Life Guards, hearing of the loss of the standard, picked up an orange scarf from the field and threw it over his shoulders. Accompanied by one or two of his comrades similarly attired, he slipped in amongst the ranks of the enemy.... Protected by his scarf, Smith succeeded in escaping hostile notice, and triumphantly laid the recovered standard at the feet of the King. Charles rewarded him with hearty thanks, and knighted him on the spot."[20]

Citations

edit- ^ a b Battle of Edgehill (1642).

- ^ Battle of Edgehill 23 October 1642.

- ^ Young 1995, p. 71.

- ^ Young 1995, p. 75.

- ^ Knowles 2009.

- ^ The Cromwell Museum.

- ^ Young 1995, p. 79.

- ^ Murdoch and Grosjean 2014, pp. 120–123.

- ^ a b c Young & Holmes 2000, p. 74.

- ^ Young 1995, p. 104.

- ^ Young & Holmes 2000, pp. 78–79.

- ^ Young 1995, pp. 114–115.

- ^ Platt 2017.

- ^ Murdoch and Grosjean 2014, p. 122.

- ^ The final days of the old Scottish regiments.

- ^ Walsh 2011, p. 8.

- ^ Carlton 1992, p. 193.

- ^ Roberts & Tincey 2001, p. 72.

- ^ Hyde 1702.

- ^ Gardiner 1894, pp. 49–50.

References

edit- "Battle of Edgehill 23rd October 1642". UK Battlefields Resource Centre. The Battlefields Trust. 2020. Retrieved 21 January 2013.

- "Battle of Edgehill (1642)". Battlefields of Britain. CastlesFortsBattles.co.uk network. 2019. Archived from the original on 10 May 2021. Retrieved 19 May 2020.

- Carlton, Charles (1992), Going to the Wars: The Experience of the British Civil Wars, 1638–1651, Routledge, p. 192, ISBN 0-415-10391-6

- The Cromwell Museum. "Soldier | Cromwell". www.cromwellmuseum.org. The Cromwell Museum. Retrieved 9 June 2024.

- "The final days of the old Scottish regiments". electricscotland.com. The Scotsman. 2006. Retrieved 26 April 2020.

- Gardiner, Samuel Rawson (1894). A History of the Great Civil War, 1642–1649 (Vol. 1 ed.). London: London, Longmans, Green, Co.

- Hyde, Edward (1702). The History of the Rebellion and Civil Wars in England.

- Knowles, Elizabeth, ed. (2009). Oxford Dictionary of Quotations (7th ed.). Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780199237173.

- Murdoch, Steve; Grosjean, Alexix (2014). Alexander Leslie and the Scottish Generals of the Thirty Years' War, 1618–1648. London: Pickering & Chatto.

- Platt, Jerome J. (2017). "Q&A: British Historical Medals of the 17th Century". English Civil War.org. Struan Bates. Retrieved 25 April 2020.

- Roberts, Keith; Tincey, John (2001), Edgehill 1642: First Battle of the English Civil War, Osprey, ISBN 1-85532-991-3

- Young, Peter (1995) [1967], Edgehill 1642, Moreton-in-Marsh: Windrush Press, ISBN 0-900075-34-1

- Young, Peter; Holmes, Richard (2000) [First published 1974], The English Civil War, Ware: Wordsworth Editions, ISBN 1-84022-222-0

- Walsh, Sir Robert (2011). A True Narrative and Manifest (EEBO ed.). ISBN 978-1240940394.

Further reading

edit- Scott, C.L.; Turton, A; Gruber von Arni, E. (2004), Edgehill: The Battle Reinterpreted, Barnsley, South Yorkshire: Pen & Sword Military, ISBN 1-84415-133-6

- Seymour, W (1997) [1975], Battles in Britain, 1066–1746 (2nd, first published as Volume 2, 1642–1746 ed.), Hertfordshire: Wordsworth, ISBN 1-85326-672-8

- Winder, Robert (9 May 1999), "It's a grand life for Chelsea's men in scarlet", The Independent

External links

edit- BattleOfEdgehillExhibitionRadway.org.uk – Permanent Battle of Edgehill exhibition within Radway's church

- British Civil Wars site Archived 9 December 2008 at the Wayback Machine

- Photos of some of the areas involved in the Battle of Edgehill on geograph