An all-points bulletin (APB) is an electronic information broadcast sent from one sender to a group of recipients, to rapidly communicate an important message.[1] The technology used to send this broadcast has varied throughout time, and includes teletype, radio, computerized bulletin board systems (CBBS), and the Internet.[2]

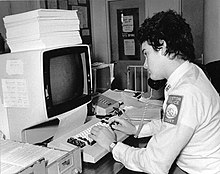

Police used all-points bulletins to send messages via a computer. | |

| Other names | APB, BOLO |

|---|---|

| Uses | Policing, politics |

| Types | Computer, radio, paper |

The earliest known record of the all-points bulletin is when used by United States police, which dates the term to 1947. Although used in the field of policing at the time, the APB has had usage in fields such as politics, technology and science research. However, since the 21st century, due to advances in technology, all-points bulletins have become significantly less common and are now only primarily used by police departments in countries such as the United States, Canada, Australia and the United Kingdom.

Technological functionality

editPre-21st century

editThe functionality of all-points bulletins was based on the latest advances in computer networking at the time, developed in the 1940s and continuing evolution through to the 1970s. Different from e-mail or teleconferencing, which are designed for a limited list of recipients, all-points bulletins were digital message "broadcast systems."[3] It is described that "each message placed on [an APB] is intended for a wide audience," and they were some of the first technologies which could do so in an efficient and effective manner.[3]

Users access these all-points bulletins "through terminals or microcomputers by dialling in over dedicated or general-purpose telecommunication lines." The APB then shows messages that will be readable for the users of the system, and in some systems, users are able to attach their own messages similar to a virtual bulletin board.[3] Consequently, messages would not only be able to be seen by the sender, but also by subsequent users of the digital bulletin system, who could also add their own information and messages to this bulletin. Users were thus able to build information upon one another, enabling discussion of ideas and information between individuals in society, despite using different computers in different locations.[2]

However, in regard to the technical functionality of the computerized bulletin systems, there is a lack of significant research on the technical construction and development of these terminals and computers. Thus, modern knowledge of the technicalities of these older all-points bulletin systems is restricted.

In the 21st century

editThe modern technological evolution of the all-points bulletin is mainly only used in the world of policing.[4] Police officers will use computers, both at the police station and fitted in their vehicles, connected to a private police intranet, to access APBs. Other forms of media that perform similar functions to APBs include smartphone apps and internet web pages.[4] Besides in the field of policing, APBs are almost completely out of use in 21st century society. Due to the rapid evolution of the internet and other technology beginning in the early 2000s, the all-points bulletin is becoming an increasingly less useful method of communicating messages, and less information is being published about it.

Uses

editPolicing

editIn the field of policing, an all-points bulletin contains an important message about a suspect or item of interest, which officers may be in search for. They are primarily used for individuals who are classified as dangerous and for crimes of high priority.[1] In these fields, the APB may also be known as a BOLO, for "be on (the) look-out", and ATL, for "Attempt to Locate".[5]

In the "event the radio is not a viable means for transmitting data (i.e., radio traffic is busy)", the police officer will use the digital all-points bulletin.[6] The officer enters the same exact information into the mobile computer terminal. By doing this, they are able to make the message equivalent to a radio message, with the same codes.[7] This allows the same automated information to be gathered by other police officers who are receiving the bulletin.

Catching wanted fugitives

editIn 1970, Farmville Police department in North Carolina, United States, reported about their implementation of the all-points bulletin (APB) system beginning in 1968.[1] If a stolen car was reported, officers would send out a radio broadcast to all patrol cars and to various other stations within a certain radius. In relatively short time, the message can be relayed around the state. However, after the introduction of the bulletin, the similar function can be done, but faster. Police can send out an APB that will reach thirteen states, through the use of teletype.[1] Officers also used the APB if they were required to notify individuals about the death of family members.

In 1973, in Oglala, South Dakota, two FBI agents and a Native American activist were killed.[8] "Five months after a firefight at Oglala, an all-points bulletin was issued by the Portland FBI for a motorhome and a station wagon carrying federal fugitives". The bulletin cautioned, "Do not stop, but advise FBI." Soon after the bulletin was released, the vehicles were located, and the fugitives were arrested.[8]

Finding missing persons

editIn 1967, Los Angeles County Road Department discovered parts of a human skeleton in the Angeles National Forest.[9] The department issued an all-points bulletin with a thorough description of the skeleton, using x-ray data and autopsy, which received numerous responses from various missing persons bureaus. From this, Police Department records showed that a person of similar description was reported to have disappeared on 19 March 1966. After several follow-ups with hospitals using x-rays and medical records, the remains were confirmed to be that person and the case was closed.[9]

Counter-terrorism

editThe all-points bulletin was used months prior to the 9/11 attacks in the US with regards to terrorism. Prior to the 9/11 attacks, for 21 months, the CIA had identified "two terrorists" living in the United States.[10] After an all-points bulletin was later issued for the men on 23 August 2001 for the police to track the men, it was insufficient time for the police to track the men.[10]

Alternate versions

editIn Australia, a similar, longer acronym for the all-points bulletin that is used by New South Wales and Victoria Police law enforcement is KALOF or KLO4 (for "keep a look-out for").[4] Queensland used to use BOLF (be on the lookout for), and now, with Western Australia Police, use LOTBKF ('Look Out To Be Kept For').[11] The United Kingdom uses a similar system known as the all-ports warning or APW, which circulates a suspect's description to airports, ports and international railway stations to detect an offender or suspect leaving the country. Due to the high numbers of commuters at such places, British police forces often use the all-points warning to contact specific airports, ports or stations and circulate descriptions individually using all-points bulletins.[4]

Politics

editAll-points bulletins have been used in politics, where users are able to leave messages, read messages left by others previously, and respond to others' messages. In 1986, the electronic all-points bulletins were being used by politicians as another means of communicating with voters.[2] Politicians would use APBs "to inform constituents about their recent activities and how they stand on selected issues", improving their "interactive capability" with the electorate.[2]

Additionally, APBs had functioning two-way communication systems, where voters were able to write messages back to the politicians via the computer keyboard.[2] This enabled voters to respond to politicians about their own stances on certain issues and to engage in digital discussions with one another and also the politicians. This ability to discuss ideas and politics without being in-person was previously not done before in political history.

Due to this and other "additional unique features", political APBs simply offered new abilities that platforms traditional media such as newspapers and televisions at the time could not and opened new doors for politicians.[12] However, overall access to political APBs was very limited, with CompuServe (leading digital APB provider) having 150,000 subscribers and the penetration rate for personal computers reached 14% in 1984.[12]

Environment

editThe phrase an "all-points bulletin" was used to describe the report of the sudden disappearance of cheatgrass near Winnemucca, Nevada in 2003.[13] That spring, a rangeland manager in the Winnemucca office of the Bureau of Land Management noticed that large areas usually covered by cheatgrass were bare.[13] A local rancher helped Cindy Salo, PhD identify an outbreak of army cutworms as the most likely cause of the cheatgrass disappearance in Nevada.[13] Salo's findings allowed her to predict a similar army cutworm outbreak in northwest Nevada and southwest Idaho in 2014.[14]

Medical discovery

editIn search of a gene linked to a poorly known bone disease known as fibrodysplasia ossificans progressiva (FOP), scientist Frederick Kaplan issued an internet-based all-points bulletin to doctors worldwide asking for any families with FOP to go to him for study.[15] He did this via online articles and electronic mail. In response to the bulletin, Kaplan and his team were able to obtain 50 willing patients to run their experimentation with. Eventually, he and his team were in fact able to identify the gene responsible, known as the ACVR1 mutation.[15] This would go on to allow deeper research about the disease, and potentially allow for the development of a treatment for the disease.

Future

editIn May 2010, Scientific American medical editor Christine Soares proposed that a "modern all-points bulletin" may take the shape of what is known as forensic profiling. This technology would allow police detectives to describe a suspect's pigmentation, ancestry, and likelihood of being obese, a smoker, or an alcoholic.[16] Far beyond using DNA "fingerprints" to link an individual to a crime scene, it would enhance police ability to develop sketches of unknown persons by reading traits inscribed in their DNA.[16] In 2020, established Harvard professor Jonathan Zittrain published speculations about future evolution of the all-points bulletin. Zittrain argues that in the future, the act of sending out an all-points bulletin will take the form of "asking millions of distributed scanners to check for a particular identity and summon police if found".[17]

See also

editReferences

edit- ^ a b c d Reiter, E. (1970). Police strive to provide protection machines lend valuable assistance. Rotunda. 48(9) 1–3.

- ^ a b c d e Garramone, G. M., Harris, A. C., & Anderson, R. (1986). Uses of political computer bulletin boards. Journal of Broadcasting & Electronic Media, 30(3), 325–339, DOI: 10.1080/08838158609386627

- ^ a b c Rafaeli, S. (1984). The electronic bulletin board: A computer-driven mass medium. Social Science Micro Review, 2(3), 123–136. https://doi.org/10.1177/089443938600200302

- ^ a b c d "All Points Bulletin/All Ports Warning". Police Specials. Archived from the original on 19 May 2009. Retrieved 15 June 2010.

- ^ Whitney, Erin (6 December 2017) [4 March 2014]. "The Definitive Guide to Understanding 'True Detective'". The Huffington Post. Retrieved 7 April 2024.

- ^ Walker, Samuel (1 June 2001). "Searching for the Denominator: Problems with Police Traffic Stop Data and an Early Warning System Solution". Justice Research and Policy. 3 (1): 63–95. doi:10.3818/jrp.3.1.2001.63. ISSN 1525-1071. S2CID 76655168 – via sagepub.

- ^ Lansdowne, W. M. (2000). Vehicle stop demographic study. San Jose, CA: San Jose Police Department.

- ^ a b Zimmerman, Loretta Ellen (1995). "Review of Left by the Indians; Massacre on the Oregon Trail in the Year 1860; On Her Way Rejoicing: Keturah Belknap's Chronicles". Oregon Historical Quarterly. 96 (2/3): 285–287. ISSN 0030-4727. JSTOR 20614658.

- ^ a b Kade, Harold; Meyers, Harvey; Wahlke, James E. (1 June 1967). "Identification of Skeletonized Remains by X-Ray Comparison". The Journal of Criminal Law, Criminology, and Police Science. 58 (2): 261. doi:10.2307/1140853. JSTOR 1140853.

- ^ a b Rosen, J. (2001). Media Smackdown! (Free Press). American Journalism Review, 23(10), 14+. https://link.gale.com/apps/doc/A81389460/AONE?u=usyd&sid=googleScholarFullText&xid=fce357ea

- ^ "BOLF – stolen motorcycle". myPolice Mackay. State of Queensland (Queensland Police Service). 8 May 2014. Retrieved 30 January 2022.

See also various Queensland Government Hansard reports

- ^ a b Levy, S. (1984). Personal computers: 'Big blue' calls the tune. Channels of communications: The essential 1985 field guide to the electronic media (pp. 14–15). New York: Media Commentary Council

- ^ a b c Salo, Cindy (2011). "Land Lines: The Cheatgrass That Wasn't There". Rangelands. 33 (3): 60–62. doi:10.2111/1551-501X-33.3.60. ISSN 0190-0528. JSTOR 23013306. S2CID 85323701.

- ^ Salo, Cindy (2018). "Army cutworm outbreak produced cheatgrass 'die-offs' and defoliated shrubs in southwest Idaho, 2014" (PDF). Rangelands. 40 (3): 99–105. doi:10.1016/j.rala.2018.05.003.

- ^ a b Couzin, Jennifer (2006). "Bone Disease Gene Finally Found". Science. 312 (5773): 514–515. doi:10.1126/science.312.5773.514b. ISSN 0036-8075. JSTOR 3845908. PMID 16645061. S2CID 83103117.

- ^ a b Soares, Christine (May 2010). "Portrait in DNA". Scientific American. 302 (5): 14–17. Bibcode:2010SciAm.302e..14S. doi:10.1038/scientificamerican0510-14. ISSN 0036-8733. JSTOR 26002017. PMID 20443366. Retrieved 7 April 2024.

- ^ Zittrain, J. (28 October 2008). "Ubiquitous Human Computing". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society A: Mathematical, Physical and Engineering Sciences. 366 (1881): 3813–3821. Bibcode:2008RSPTA.366.3813Z. doi:10.1098/rsta.2008.0116. PMID 18672463.