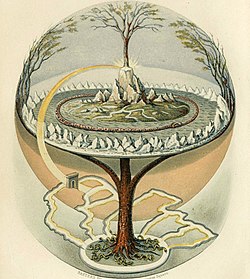

The world tree is a motif present in several religions and mythologies, particularly Indo-European, Siberian, and Native American religions. The world tree is represented as a colossal tree which supports the heavens, thereby connecting the heavens, the terrestrial world, and, through its roots, the underworld. It may also be strongly connected to the motif of the tree of life, but it is the source of wisdom of the ages.

Specific world trees include Égig érő fa in Hungarian mythology, Ağaç Ana in Turkic mythology, Kenac' Car[1] in Armenian mythology, Modun in Mongol mythology, Yggdrasil in Norse mythology, Irminsul in Germanic mythology, the oak in Slavic, Finnish and Baltic, Jianmu (Chinese: 建木; pinyin: jiànmù) in Chinese mythology, and in Hindu mythology the Ashvattha (a Ficus religiosa).

General description

editDiffusion

editScholarship states that many Eurasian mythologies share the motif of the "world tree", "cosmic tree", or "Eagle and Serpent Tree".[2] More specifically, it shows up in "Haitian, Finnish, Lithuanian, Hungarian, Indian, Chinese, Japanese, Norse, Siberian and northern Asian Shamanic folklore".[3]

Tripartite division of the world

editThe World Tree is often identified with the Tree of Life,[4] and also fulfills the role of an axis mundi, that is, a centre or axis of the world.[5][3] It is also located at the center of the world and represents order and harmony of the cosmos.[6] According to Loreta Senkute, each part of the tree corresponds to one of the three spheres of the world (treetops – heavens; trunk – middle world or earth; roots – underworld) and is also associated with a classical element (top part – fire; middle part – earth, soil, ground; bottom part – water).[6]

Its branches are said to reach the skies and its roots to connect the human or earthly world with an underworld or subterranean realm. Because of this, the tree was worshipped as a mediator between Heavens and Earth.[7] On the treetops are located the luminaries (stars) and heavenly bodies,[8] along with an eagle's nest; several species of birds perch among its branches; humans and animals of every kind live under its branches, and near the root is the dwelling place of snakes and every sort of reptiles.[9][10]

Motifs

editThe imagery of the World Tree is sometimes associated with conferring immortality, either by a fruit that grows on it or by a springsource located nearby.[11][4] As George Lechler also pointed out, in some descriptions this "water of life" may also flow from the roots of the tree.[12]

Zoological imagery

editAccording to Vladimir Toporov, animal species are commonly distributed along the parts of the tree: between its roots, figure "chthonic animals", such as snakes and frogs, but he also mentions aquatic animals such as otters, beavers, and fishes, as well as dragons; the middle part of the tree is reserved for hoofed animals such as deer or elk (sometimes bees), and on the topmost part perches the "principal" bird, or a pair of birds sat on either side of the tree crown.[13]

A bird perches atop its foliage, "often .... a winged mythical creature" that represents a heavenly realm.[14][4] The eagle seems to be the most frequent bird, fulfilling the role of a creator or weather deity.[15] Its antipode is a snake or serpentine creature that crawls between the tree roots, being a "symbol of the underworld".[14][4]

Similar motifs

editThe World Tree has also been compared to a World Pillar that appears in other traditions and functions as separator between the earth and the skies, upholding the latter.[16] Another representation akin to the World Tree is a separate World Mountain. However, in some stories, the world tree is located atop the world mountain, in a combination of both motifs.[6]

A conflict between a serpentine creature and a giant bird (an eagle) occurs in Eurasian mythologies: a hero kills the serpent that menaces a nest of little birds, and their mother repays the favor – a motif comparativist Julien d'Huy dates to the Paleolithic. A parallel story is attested in the traditions of the indigenous peoples of the Americas, where the thunderbird is slotted into the role of the giant bird whose nest is menaced by a "snake-like water monster".[17][18]

Relation to shamanism

editRomanian historian of religion, Mircea Eliade, in his monumental work Shamanism: Archaic Techniques of Ecstasy, suggested that the world tree was an important element in shamanistic worldview.[19] Also, according to him, "the giant bird ... hatches shamans in the branches of the World Tree".[19] Likewise, Roald Knutsen indicates the presence of the motif in Altaic shamanism.[20] Representations of the world tree are reported to be portrayed in drums used in Siberian shamanistic practices.[21]

Some species of birds (eagle, raven, crane, loon, and lark) are revered as mediators between worlds and also connected to the imagery of the world tree.[22] Another line of scholarship points to a "recurring theme" of the owl as the mediator to the upper realm, and its counterpart, the snake, as the mediator to the lower regions of the cosmos.[23]

Researcher Kristen Pearson mentions Northern Eurasian and Central Asian traditions wherein the World Tree is also associated with the horse and with deer antlers (which might resemble tree branches).[24]

Possible origins

editMircea Eliade proposed that the typical imagery of the world tree (bird at the top, snake at the root) "is presumably of Oriental origin".[19] Likewise, Roald Knutsen indicates a possible origin of the motif in Central Asia and later diffusion into other regions and cultures.[20]

In specific cultures

editIndigenous American cultures

edit- Among Indigenous Mesoamerican cultures, the concept of "world trees" is a prevalent motif in Mesoamerican cosmologies and iconography. The Temple of the Cross Complex at Palenque contains one of the most studied examples of the world tree in architectural motifs of all Mayan ruins. World trees embodied the four cardinal directions, which represented also the fourfold nature of a central world tree, a symbolic axis mundi connecting the planes of the Underworld and the sky with that of the terrestrial world.[25]

- Depictions of world trees, both in their directional and central aspects, are found in the art and traditions of cultures such as the Maya, Aztec, Izapan, Mixtec, Olmec, and others, dating to at least the Mid/Late Formative periods of Mesoamerican chronology. Among the Maya, the central world tree was conceived as, or represented by, a ceiba tree, called yax imix che ('blue-green tree of abundance') by the Book of Chilam Balam of Chumayel.[26] The trunk of the tree could also be represented by an upright caiman, whose skin evokes the tree's spiny trunk.[25] These depictions could also show birds perched atop the trees.[27]

- A similarly named tree, yax cheel cab ('first tree of the world'), was reported by 17th-century priest Andrés de Avendaño to have been worshipped by the Itzá Maya. However, scholarship suggests that this worship derives from some form of cultural interaction between "pre-Hispanic iconography and [millenary] practices" and European traditions brought by the Hispanic colonization.[27]

- Directional world trees are also associated with the four Yearbearers in Mesoamerican calendars, and the directional colors and deities. Mesoamerican codices which have this association outlined include the Dresden, Borgia and Fejérváry-Mayer codices.[27] It is supposed that Mesoamerican sites and ceremonial centers frequently had actual trees planted at each of the four cardinal directions, representing the quadripartite concept.

- World trees are frequently depicted with birds in their branches, and their roots extending into earth or water (sometimes atop a "water-monster", symbolic of the underworld).

- The central world tree has also been interpreted as a representation of the band of the Milky Way.[28]

- Izapa Stela 5 contains a possible representation of a world tree.

A common theme in most indigenous cultures of the Americas is a concept of directionality (the horizontal and vertical planes), with the vertical dimension often being represented by a world tree. Some scholars have argued that the religious importance of the horizontal and vertical dimensions in many animist cultures may derive from the human body and the position it occupies in the world as it perceives the surrounding living world. Many Indigenous cultures of the Americas have similar cosmologies regarding the directionality and the world tree, however the type of tree representing the world tree depends on the surrounding environment. For many Indigenous American peoples located in more temperate regions for example, it is the spruce rather than the ceiba that is the world tree; however the idea of cosmic directions combined with a concept of a tree uniting the directional planes is similar.

Greek mythology

editLike in many other Indo-European cultures, one tree species was considered the World Tree in some cosmogonical accounts.

Oak tree

editThe sacred tree of Zeus is the oak,[29] and the one at Dodona (famous for the cultic worship of Zeus and the oak) was said by later tradition to have its roots furrow so deep as to reach the confines of Tartarus.[30]

In a different cosmogonic account presented by Pherecydes of Syros, male deity Zas (identified as Zeus) marries female divinity Chthonie (associated with the earth and later called Gê/Gaia), and from their marriage sprouts an oak tree. This oak tree connects the heavens above and its roots grew into the Earth, to reach the depths of Tartarus. This oak tree is considered by scholarship to symbolize a cosmic tree, uniting three spheres: underworld, terrestrial and celestial.[31]

Other trees

editBesides the oak, several other sacred trees existed in Greek mythology. For instance, the olive, named Moriai, was the world tree and associated with the Olympian goddess Athena.

In a separate Greek myth the Hesperides live beneath an apple tree with golden apples that was given to the highest Olympian goddess Hera by the primal Mother goddess Gaia at Hera's marriage to Zeus.[32] The tree stands in the Garden of the Hesperides and is guarded by Ladon, a dragon. Heracles defeats Ladon and snatches the golden apples.

In the epic quest for the Golden Fleece of Argonautica, the object of the quest is found in the realm of Colchis, hanging on a tree guarded by a never-sleeping dragon (the Colchian dragon).[33] In a version of the story provided by Pseudo-Apollodorus in Bibliotheca, the Golden Fleece was affixed by King Aeetes to an oak tree in a grove dedicated to war god Ares.[34] This information is repeated in Valerius Flaccus's Argonautica.[35] In the same passage of Valerius Flaccus' work, King Aeetes prays to Ares for a sign and suddenly a "serpent gliding from the Caucasus mountains" appears and coils around the grove as to protect it.[36]

Roman mythology

editIn Roman mythology the world tree was the olive tree, that was associated with Pax. The Greek equivalent of Pax is Eirene, one of the Horae. The Sacred tree of the Roman Sky father Jupiter was the oak, the laurel was the Sacred tree of Apollo. The ancient fig-tree in the Comitium at Rome, was considered as a descendant of the very tree under which Romulus and Remus were found.[29]

Norse mythology

editIn Norse mythology, Yggdrasil is the world tree.[10] Yggdrasil is attested in the Poetic Edda, compiled in the 13th century from earlier traditional sources, and the Prose Edda, written in the 13th century by Snorri Sturluson. In both sources, Yggdrasil is an immense ash tree that is central and considered very holy. The Æsir go to Yggdrasil daily to hold their courts. The branches of Yggdrasil extend far into the heavens, and the tree is supported by three roots that extend far away into other locations: one to the well Urðarbrunnr in the heavens, one to the spring Hvergelmir, and another to the well Mímisbrunnr. Creatures live within Yggdrasil, including the harts Dáinn, Dvalinn, Duneyrr and Duraþrór, the giant in eagle-shape Hræsvelgr, the squirrel Ratatoskr and the wyrm Níðhöggr. Scholarly theories have been proposed about the etymology of the name Yggdrasil, the potential relation to the trees Mímameiðr and Læraðr, and the sacred tree at Uppsala.

Circumbaltic mythology

editIn Baltic, Slavic and Finnish mythology, the world tree is usually an oak.[10][a] Most of the images of the world tree are preserved on ancient ornaments. Often on the Baltic and Slavic patterns there was an image of an inverted tree, "growing with its roots up, and branches going into the ground".

Baltic beliefs

editScholarship recognizes that Baltic beliefs about a World Tree, located at the central part of the Earth, follow a tripartite division of the cosmos (underworld, earth, sky), each part corresponding to a part of the tree (root, trunk, branches).[38][39]

It has been suggested that the word for "tree" in Baltic languages (Latvian mežs; Lithuanian medis), both derived from Proto-Indo-European *medh- 'middle', operated a semantic shift from "middle" possibly due to the belief of the Arbor Mundi.[40]

Lithuanian culture

editThe world tree (Lithuanian: Aušros medis) is widespread in Lithuanian folk painting, and is frequently found carved into household furniture such as cupboards, towel holders, and laundry beaters.[41][42][43] According to Lithuanian scholars Prane Dunduliene and Norbertas Vėlius, the World Tree is "a powerful tree with widespread branches and strong roots, reaching deep into the earth". The recurrent imagery is also present in Lithuanian myth: on the treetops, the luminaries and eagles, and further down, amidst its roots, the dwelling place of snakes and reptiles.[9] The World Tree of Lithuanian tradition was sometimes identified as an oak or a maple tree.[39]

Latvian culture

editIn Latvian mythology the world tree (Latvian: Austras koks) was one of the most important beliefs, also associated with the birth of the world. Sometimes it was identified as an oak or a birch, or even replaced by a wooden pole.[39] According to Ludvigs Adamovičs's book on Latvian folk belief, ancient Latvian mythology attested the existence of a Sun Tree as an expression of the World Tree, often described as "a birch tree with three leaves or forked branches where the Sun, the Moon, God, Laima, Auseklis (the morning star), or the daughter of the Sun rest[ed]".[44]

Slavic beliefs

editAccording to Slavic folklore, as reconstructed by Radoslav Katičić, the draconic or serpentine character furrows near a body of water, and the bird that lives on the treetop could be an eagle, a falcon or a nightingale.[45]

Scholars Ivanov and Toporov offered a reconstructed Slavic variant of the Indo-European myth about a battle between a Thunder God and a snake-like adversary. In their proposed reconstruction, the Snake lives under the World Tree, sleeping on black wool. They surmise this snake on black wool is a reference to a cattle god, known in Slavic mythology as Veles.[46]

Further studies show that the usual tree that appears in Slavic folklore is an oak: for instance, in Czech, it is known as Veledub ('The Great Oak').[47]

In addition, the world tree appears in the Island of Buyan, on top of a stone. Another description shows that legendary birds Sirin and Alkonost make their nests on separate sides of the tree.[48]

Ukrainian scholarship points to the existence of the motif in "archaic wintertime songs and carols": their texts attest a tree at the center of the world and two or three falcons or pigeons sat on its top, ready to dive in and fetch mud to create land (the Earth diver cosmogonic motif).[49][50]

The imagery of the world tree also appears in folk medicine of the Don Cossacks.[51]

Finnic mythology

editAccording to scholar Aado Lintrop, Estonian mythology records two types of world tree in Estonian runic songs, with similar characteristics of being an oak and having a bird at the top, a snake at the roots and the stars amongst its branches.[10]

Judeo-Christian mythology

editThe Tree of the knowledge of good and evil and the Tree of life are both components of the Garden of Eden story in the Book of Genesis in the Bible. According to Jewish mythology, in the Garden of Eden there is a tree of life or the "tree of souls" that blossoms and produces new souls, which fall into the Guf, the Treasury of Souls.[52] The Angel Gabriel reaches into the treasury and takes out the first soul that comes into his hand. Then Lailah, the Angel of Conception, watches over the embryo until it is born.[53]

Gnosticism

editAccording to the Gnostic codex On the Origin of the World, the tree of immortal life is in the north of paradise, which is outside the circuit of the Sun and Moon in the luxuriant Earth. Its height is so great it reaches Heaven. Its leaves are described as resembling cypress, the color of the tree is like the Sun, its fruit is like clusters of white grapes and its branches are beautiful. The tree will provide life for the innocent during the consummation of the age.[54]

Mandaean scrolls often include abstract illustrations of world trees that represent the living, interconnected nature of the cosmos.[55] In Mandaeism, the date palm (Mandaic: sindirka) symbolizes the cosmic tree and is often associated with the cosmic wellspring (Mandaic: aina). The date palm and wellspring are often mentioned together as heavenly symbols in Mandaean texts. The date palm takes on masculine symbolism, while the wellspring takes on feminine symbolism.[56]

Armenian mythology

editArmenian professor Hrach Martirosyan argues for the presence, in Armenian mythology, of a serpentine creature named Andndayin ōj, that lives in the (abyssal) waters that circundate the World Tree.[57]

Georgian mythology

editAccording to scholarship, Georgian mythology also attests a rivalry between mythical bird Paskunji, which lives in the underworld on the top of a tree, and a snake that menaces its nestlings.[58][59][60]

Hittite culture

editA similar imagery is attested in Hittite literature: a snake encircles the base of a tree, an eagle perches atop it, and a bee occupies its middle,[61][62] which Craig Melchert considers to be a version of the "world tree" or "tree of life" motif.[63]

Mesopotamian traditions

editSumerian culture

editProfessor Amar Annus states that, although the motif seems to originate much earlier, its first attestation in world culture occurred in Sumerian literature, with the tale of "Gilgamesh, Enkidu, and the Netherworld".[2] According to this tale, goddess Innana transplants the huluppu tree to her garden in the City of Uruk, for she intends to use its wood to carve a throne. However, a snake "with no charm", a ghostly figure (Lilith or another character associated with darkness) and the legendary Anzû-bird make their residence on the tree, until Gilgamesh kills the serpent and the other residents escape.[2][4]

Akkadian literature

editIn fragments of the story of Etana, there is a narrative sequence about a snake and an eagle that live on opposite sides of a poplar tree (şarbatu), the snake on its roots, the eagle on its foliage. At a certain point, both animals swear before deity Shamash and share their meat with each other, until the eagle's hatchlings are born and the eagle decides to eat the snake's young ones. In revenge, the snake alerts god Shamash, who agrees to let the snake punish the eagle for the perceived affront. Later, Shamash takes pity on the bird's condition and sets hero Etana to release it from its punishment. Later versions of the story associate the eagle with mythical bird Anzû and the snake with a serpentine being named Bašmu.[64][65]

Iranian mythology

editA world tree is a common motif in Persian mythology, the legendary bird Simurgh (alternatively, Saēna bird; Sēnmurw and Senmurv) perches atop a tree in the center of the sea Vourukasa. This tree is described as having all-healing properties and many seeds.[66] In another account, the tree is the very same tree of the White Hōm (Haōma).[67] Gaokerena or white Haoma is a tree whose vivacity ensures continued life in the universe,[68] and grants immortality to "all who eat from it". In the Pahlavi Bundahishn, it is said that evil god Ahriman created a lizard to attack the tree.[15]

Bas tokhmak is another remedial tree; it retains all herbal seeds and destroys sorrow.[69]

Hinduism and Indian religions

editRemnants are also evident in the Kalpavriksha ("wish-fulfilling tree") and the Ashvattha tree of the Indian religions. The Ashvattha tree ('keeper of horses') is described as a sacred fig and corresponds to "the most typical representation of the world tree in India", upon whose branches the celestial bodies rest.[4][15] Likewise, the Kalpavriksha is also equated with a fig tree and said to possess wish-granting abilities.[70]

Indologist David Dean Shulman provided the description of a similar imagery that appears in South Indian temples: the sthalavṛkṣa tree. The tree is depicted alongside a water source (river, temple tank, sea). The tree may also appear rooted on Earth or reaching the realm of Patala (a netherworld where the Nāga dwell), or in an inverted position, rooted in the Heavens. Like other accounts, this tree may also function as an axis mundi.[71]

North Asian and Siberian cultures

editThe world tree is also represented in the mythologies and folklore of North Asia and Siberia. According to Mihály Hoppál, Hungarian scholar Vilmos Diószegi located some motifs related to the world tree in Siberian shamanism and other North Asian peoples. As per Diószegi's research, the "bird-peaked" tree holds the sun and the moon, and the underworld is "a land of snakes, lizards and frogs".[72]

In the mythology of the Samoyeds, the world tree connects different realities (underworld, this world, upper world) together. In their mythology the world tree is also the symbol of Mother Earth who is said to give the Samoyed shaman his drum and also help him travel from one world to another. According to scholar Aado Lintrop, the larch is "often regarded" by Siberian peoples as the World Tree.[4]

Scholar Aado Lintrop also noted the resemblance between an account of the World Tree from the Yakuts and a Moksha-Mordvinic folk song (described as a great birch).[4]

The imagery of the world tree, its roots burrowing underground, its branches reaching upward, the luminaries in its branches is also present in the mythology of Finno-Ugric peoples from Northern Asia, such as the Khanty and the Mansi.[73]

Mongolic and Turkic folk beliefs

editThe symbol of the world tree is also common in Tengrism, an ancient religion of Mongols and Turkic peoples. The world tree is sometimes a beech,[74] a birch, or a poplar in epic works.[75]

Scholarship points out the presence of the motif in Central Asian and North Eurasian epic tradition: a world tree named Bai-Terek in Altai and Kyrgyz epics; a "sacred tree with nine branches" in the Buryat epic.[76]

Turkic cultures

editBai-Terek

editThe Bai-Terek (also known as bayterek, beyterek, beğterek, begterek, begtereg),[77] found, for instance, in the Altai Maadai Kara epos, can be translated as "Golden Poplar".[78] Like the mythological description, each part of tree (top, trunk and root) corresponds to the three layers of reality: heavenly, earthly and underground. In one description, it is considered the axis mundi. It holds at the top "a nest of a double-headed eagle that watches over the different parts of the world" and, in the form of a snake, Erlik, deity of the underworld, tries to slither up the tree to steal an egg from the nest.[77] In another, the tree holds two gold cuckoos at the topmost branches and two golden eagles just below. At the roots there are two dogs that guard the passage between the underworld and the world of the living.[78]

Aal Luuk Mas

editAmong the Yakuts, the world tree (or sacred tree) is called Ál Lúk Mas (Aal Luuk Mas) and is attested in their Olonkho epic narratives. Furthermore, this sacred tree is described to "connect the three worlds (Upper, Middle and Lower)", the branches to the sky and the roots to the underworld.[76] Further studies show that this sacred tree also shows many alternate names and descriptions in different regional traditions.[76] According to scholarship, the prevalent animal at the top of the tree in the Olonkho is the eagle.[79]

Researcher Galina Popova emphasizes that the motif of the world tree offers a binary opposition between two different realms (the Upper Realm and the Underworld), and Aal Luuk Mas functions as a link between both.[80] A spirit or goddess of the earth, named Aan Alahchin Hotun, is also said to inhabit or live in the trunk of Aal Luuk Mas.[80]

Bashkir

editAccording to scholarship, in the Bashkir epic Ural-batyr, deity Samrau is described as a celestial being married to female deities of the Sun and the Moon. He is also "The King of the Birds" and is opposed by the "dark forces" of the universe, which live in the underworld. A similarly named creature, the bird Samrigush, appears in Bashkir folktales living atop the tallest tree in the world and its enemy is a snake named Azhdakha.[81][82] After the human hero kills the serpent Azhdakha, the grateful Samrigush agrees to carry him back to the world of light.[83]

Kazakh

editScholarship points to the existence of a bird named Samurik (Samruk) that, according to Kazakh myth, lives atop the World Tree Baiterek. Likewise, in Kazakh folktales, it is also the hero's carrier out of the underworld, after he defeats a dragon named Aydakhara or Aydarhana.[84] In the same vein, Kazakh literary critic and folklorist Seyt Kaskabasov described that the Samruk bird travels between the three spheres of the universe, nests atop the "cosmic tree" (bәyterek) and helps the hero out of the underworld.[85]

Other representations

editAn early 20th-century report on Altaian shamanism by researcher Karunovskaia describes a shamanistic journey, information provided by one Kondratii Tanashev (or Merej Tanas). However, A. A. Znamenski believes this material is not universal to all Altaian peoples, but pertains to the specific worldview of Tanashev's Tangdy clan. Regardless, the material showed a belief in a tripartite division of the world in sky (heavenly sphere), middle world and underworld; in the central part of the world, a mountain (Ak toson altaj sip') is located. Upon this mountain there is "a navel of the earth and water ... which also serves as the root of the 'wonderful tree with golden branches and wide leaves' (Altyn byrly bai terek)". Like the iconic imagery, the tree branches out to reach the heavenly sphere.[86]

Mongolic cultures

editFinnish folklorist Uno Holmberg reported a tale from the Kalmuck people about a dragon that lies in the sea, at the foot of a Zambu tree. In the Buryat poems, near the root of the tree a snake named Abyrga dwells.[87] He also reported a "Central Asian" narrative about the fight between the snake Abyrga and a bird named Garide – which he identified as a version of Indian Garuda.[87]

East Asia

editKorea

editThe world tree is visible in the designs of the Crown of Silla, Silla being one of the Three Kingdoms of Korea. This link is used to establish a connection between Siberian peoples and those of Korea.

China

editIn Chinese mythology, a manifestation of the world tree is the Fusang or Fumu tree.[88] In a Chinese cosmogonic myth, solar deity Xihe gives birth to ten suns. Each of the suns rests upon a tree named Fusang (possibly a mulberry tree). The ten suns alternate during the day, each carried by a crow (the "Crow of the Sun"): one sun stays on the top branch to wait its turn, while the other nine suns rest on the lower branches.[89]

Tanzania

editAn origin myth is recorded from the Wapangwa tribe of Tanzania, wherein the world is created through "a primordial tree and a termite mound".[90] As a continuation of the same tale, the animals wanted to eat the fruits of this Tree of Life, but humans intended to defend it. This led to a war between animals and humans.[91]

Kenya

editIn the agikuyu community, the "mūgumo" tree is held sacred and it is a taboo to even fetch firewood from it. In the past, the tree served as a altar to offer sacrifices as well as being a place of prayer. If a mùgumo tree falls, it is believed to be an end of an era for a "god"/dynasty and a ritual should be done by elders to cleanse the area and the community because it might be a bad omen.[citation needed]

In folk and fairy tales

editATU 301: The Three Stolen Princesses

editThe imagery of the World Tree appears in a specific tale type of the Aarne-Thompson-Uther Index, type ATU 301, "The Three Stolen Princesses", and former subtypes AaTh 301A, "Quest for a Vanished Princess" (or "Three Underground Kingdoms") and AaTh 301B, "The Strong Man and His Companions" (Jean de l'Ours and Fehérlófia). The hero journeys alone to the underworld (or a subterranean realm) to rescue three princesses. He leads them to a rope that will take them to the surface and, when the hero tries to climb up the rope, his companions cut it and the hero is stranded in the underworld. In his wanderings, he comes across a tree, on its top a nest of eggs from an eagle, a griffin or a mythical bird. The hero protects the nest from a snake enemy that slithers from the roots of the tree.[44][92][93]

Serbian scholarship recalls a Serbian mythical story about three brothers, named Ноћило, Поноћило и Зорило ("Noćilo, Ponoćilo and Zorilo") and their mission to rescue the king's daughters. Zorilo goes down the cave, rescues three princesses and with a whip changes their palaces into apples. When Zorilo is ready to go up, his brothers abandon him in the cave, but he escapes with the help of a bird.[94] Serbian scholar Pavle Sofric (sr), in his book about Serbian folkmyths about trees, noted that the tree of the tale, an ash tree (Serbian: јасен), showed a great parallel to the Nordic tree as not to be coincidental.[95][96]

While comparing Balkanic variants of the tale type ATU 301, researcher Milena Benovska-Sabkova noticed that the conflict between the snake and the eagle (bird) on the tree "was very close to the classical imagery of the World Tree".[97]

Other fairy tales

editAccording to scholarship, Hungarian scholar János Berze Nágy also associated the imagery of the World Tree with fairy tales wherein a mysterious thief comes at night to steal the golden apples of the king's prized tree.[98] This incident occurs as an alternative opening to tale type ATU 301, in a group of tales formerly classified as AaTh 301A,[b] and as the opening episode in most variants of tale type ATU 550, "Bird, Horse and Princess" (otherwise known as The Golden Bird).[100]

Likewise, historical linguist Václav Blažek argued for parallels of certain motifs of these fairy tales (the night watch of the heroes, the golden apples, the avian thief) to Ossetian Nart sagas and the Greek myth of the Garden of the Hesperides.[101] The avian thief may also be a princess cursed into bird form, such as in Hungarian tale Prince Árgyilus (hu) and Fairy Ilona[98] and in Serbian tale The Nine Peahens and the Golden Apples (both classified as ATU 400, "The Man on a Quest for the Lost Wife").[102] This second type of opening episode was identified by Romanian folklorist Marcu Beza as another introduction to swan maiden tales.[103]

See also

edit- It's a Big Big World, TV-series which takes place at a location called the "World Tree"

- Potomitan

- Rehue

- Sidrat al-Muntaha

- Tree of life (Quran)

- Ṭūbā

- The Fountain

Explanatory notes

edit- ^ Lithuanian scholar Libertas Klimka (lt) indicated that the oak was considered a sacred tree to pre-Christian Baltic religion, including being a tree associated to thunder god Perkunas.[37]

- ^ The third revision of the Aarne-Thompson classification system, made in 2004 by German folklorist Hans-Jörg Uther, subsumed both subtypes AaTh 301A and AaTh 301B into the new type ATU 301.[99]

References

edit- ^ Farnah : Indo-Iranian and Indo-European studies in honor of Sasha Lubotsky. Lucien van Beek, Alwin Kloekhorst, Guus Kroonen, Michaël Peyrot, Tijmen Pronk, Michile de Vaan. Ann Arbor: Beech Stave Press. 2018. ISBN 978-0-9895142-4-8. OCLC 1104878206.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: others (link)[page needed] - ^ a b c Annus, Amar (2009). "Review Article. The Folk-Tales of Iraq and the Literary Traditions of Ancient Mesopotamia". Journal of Ancient Near Eastern Religions. 9 (1): 87–99. doi:10.1163/156921209X449170.

- ^ a b Crews, Judith (2003). "Forest and tree symbolism in folklore". Unasylva (213): 37–43. OCLC 210755951.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Lintrop, Aado (2001). "The Great Oak and Brother-Sister". Folklore. 16: 35–58. doi:10.7592/FEJF2001.16.oak2.

- ^ Toporov, V. (1990). "The Thracian Horseman in an Indo-European Perspective". ORPHEUS. Journal of Indo-European and Thracian Studies. 18: 46–63 [48].

- ^ a b c Senkutė, Loreta. "Varuna "Rigvedoje" ir dievo įvaizdžio sąsajos su velniu baltų mitologijoje" [God Varuna o f the Rigveda as related to images in ancient Baltic mythology]. In: Rytai-Vakarai: Komparatyvistinés Studijos XII. pp. 366–367. ISBN 9789955868552.

- ^ Usačiovaitė, Elvyra. "Gyvybės medžio simbolika Rytuose ir Vakaruose" [Symbolism of the Tree of Life in the East and the West; Life tree symbols in the East and West]. In: Kultūrologija [Culturology]. 2005, t. 12, p. 313. ISSN 1822-2242.

- ^ Toporov, V. (1990). "The Thracian Horseman in an Indo-European Perspective". ORPHEUS. Journal of Indo-European and Thracian Studies. 18: 46–63 [48].

The top [of the World Tree] is correlated ... with celestial and astral symbols: the Sun and the Moon, usually placed symmetrically above the tree, on the right and on the left, less frequently stars.

- ^ a b Straižys, Vytautas; Klimka, Libertas (February 1997). "The Cosmology of the Ancient Balts". Journal for the History of Astronomy. 28 (22): S57–S81. doi:10.1177/002182869702802207. S2CID 117470993.

- ^ a b c d Kuperjanov, Andres (2002). "Names in Estonian Folk Astronomy - from 'Bird's Way' to 'Milky Way'". Folklore. 22: 49–61. doi:10.7592/FEJF2002.22.milkyway.

- ^ Paliga, Rodica (1994). "Le motif du passage. La sémiotique de l'impact culturel pré-indoeuropéen et indoeuropéen" (PDF). Dialogues d'histoire ancienne. 20 (2): 11–19. doi:10.3406/dha.1994.2172.

- ^ Lechler, George (1937). "The Tree of Life in Indo-European and Islamic Cultures". Ars Islamica. 4: 369–419. JSTOR 25167048.

- ^ Toporov, V. (1990). "The Thracian Horseman in an Indo-European Perspective". ORPHEUS. Journal of Indo-European and Thracian Studies. 18: 46–63 [48].

- ^ a b Annus, Amar & Sarv, Mari. "The Ball Game Motif in the Gilgamesh Tradition and International Folklore". In: Mesopotamia in the Ancient World: Impact, Continuities, Parallels. Proceedings of the Seventh Symposium of the Melammu Project Held in Obergurgl, Austria, November 4–8, 2013. Münster: Ugarit-Verlag – Buch- und Medienhandel GmbH. 2015. pp. 289–290. ISBN 978-3-86835-128-6.

- ^ a b c Norelius, Per-Johan (2016). "The Honey-Eating Birds and the Tree of Life: Notes on Ṛgveda 1.164.20–22". Acta Orientalia. 77: 3–70–3–70. doi:10.5617/ao.5356. S2CID 166166930.

- ^ Tolley, Clive (2013). "What is a 'World Tree', and Should We Expect to Find One Growing in Anglo-Saxon England?". Trees and Timber in the Anglo-Saxon World. pp. 177–185. doi:10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199680795.003.0009. ISBN 978-0-19-968079-5.

- ^ d'Huy, Julien (18 March 2016). "Première reconstruction statistique d'un rituel paléolithique : autour du motif du dragon". Nouvelle Mythologie Comparée (in French) (3): http://nouvellemythologiecomparee.hautetfort.com/archive/2016/03/18/julien.

- ^ Hatt, Gudmund (1949). Asiatic influences in American folklore. København: I kommission hos ejnar Munksgaard, p. 37.

- ^ a b c Fournet, Arnaud (2020). "Shamanism in Indo-European Mythologies" (PDF). Archaeoastronomy and Ancient Technologies. 8 (1): 12–29.

- ^ a b Knutsen, Roald (2011). "Cultic Symbols". Tengu. pp. 43–50. doi:10.1163/9789004218024_007. ISBN 978-1-906876-22-7.

- ^ Hultkrantz, Åke (1991). "The drum in Shamanism: some reflections". Scripta Instituti Donneriani Aboensis. 14. doi:10.30674/scripta.67194.

- ^ Balzer, Marjorie Mandelstam (1996). "Flights of the Sacred: Symbolism and Theory in Siberian Shamanism". American Anthropologist. 98 (2): 305–318. doi:10.1525/aa.1996.98.2.02a00070. JSTOR 682889.

- ^ Eastham, Anne (1998). "Magdalenians and Snowy Owls ; bones recovered at the grotte de Bourrouilla (Arancou, Pyrénées Atlantiques)/Les Magdaléniens et la chouette harfang : la Grotte de Bourrouilla, Arancou (Pyrénées Atlantiques)" (PDF). Paléo. 10 (1): 95–107. doi:10.3406/pal.1998.1131.

- ^ Pearson, Kristen. Chasing the Shaman's Steed: The Horse in Myth from Central Asia to Scandinavia. Sino-Platonic Papers nr. 269. May, 2017.

- ^ a b Miller & Taube 1993, p. 186.

- ^ Roys 1967: 100.

- ^ a b c Knowlton, Timothy W.; Vail, Gabrielle (1 October 2010). "Hybrid Cosmologies in Mesoamerica: A Reevaluation of the Yax Cheel Cab , a Maya World Tree". Ethnohistory. 57 (4): 709–739. doi:10.1215/00141801-2010-042.

- ^ Freidel, et al. (1993)[full citation needed]

- ^ a b Philpot, Mrs. J.H. (1897). The Sacred Tree; or the tree in religion and myth. London: MacMillan & Co.

- ^ Philpot, Mrs. J. H. (1897). The Sacred Tree; or the tree in religion and myth. London: MacMillan & Co. pp. 93–94.

- ^ Marmoz, Julien. "La Cosmogonie de Phérécyde de Syros". In: Nouvelle Mythologie Comparée n. 5 (2019–2020). pp. 5–41.

- ^ "Hesperides". Britannica online. Greek mythology.

- ^ Godwin, William. Lives of the Necromancers. London: F. J. Mason, 1876. p. 41.

- ^ Pseudo-Apollodorus. Bibliotheca 1.9.1. Translation by Sir James George Frazer.

- ^ Valerius Flaccus. Argonautica. Translated by Mozley, J H. Loeb Classical Library Volume 286. Cambridge, MA, Harvard University Press; London, William Heinemann Ltd. 1928. Book V. Lines 228ff.

- ^ Valerius Flaccus. Argonautica. Translated by Mozley, J H. Loeb Classical Library Volume 286. Cambridge, MA, Harvard University Press; London, William Heinemann Ltd. 1928. Book V. Lines 241 and 253ff.

- ^ Klimka, Libertas. "Medžių mitologizavimas tradicinėje lietuvių kultūroje" [Mythicization of the tree in Lithuanian folk culture]. In: Acta humanitarica universitatis Saulensis [Acta humanit. univ. Saulensis (Online)]. 2011, t. 13, pp. 22–25. ISSN 1822-7309.

- ^ Čepienė, Irena. "Kai kurie mitinės pasaulėkūros aspektai lietuvių tradicinėje kultūroje" [Certain aspects of mythical world building in Lithuanian traditional culture]. In: Geografija ir edukacija [Geography and education]. 2014, Nr. 2, p. 57. ISSN 2351-6453.

- ^ a b c Běťáková, Marta Eva; Blažek, Václav. Encyklopedie baltské mytologie. Praha: Libri. 2012. p. 178. ISBN 978-80-7277-505-7.

- ^ Kalygin, Victor (30 January 2003). "Some archaic elements of Celtic cosmology". Zeitschrift für celtische Philologie. 53 (1). doi:10.1515/ZCPH.2003.70. S2CID 162904613.

- ^ Straižys and Klimka, chapter 2.

- ^ Cosmology of the Ancient Balts – 3. The concept of the World-Tree (from the 'lithuanian.net' website. Accessed 2008-12-26.)

- ^ Klimka, Libertas. "Baltiškasis Pasaulio modelis ir kalendorius" [Baltic Model of the World and Calendar]. In: LIETUVA iki MINDAUGO. 2003. p. 341. ISBN 9986-571-89-8.

- ^ a b Ķencis, Toms (20 September 2011). "The Latvian Mythological Space in Scholarly Time". Archaeologia Baltica. 15: 144–157. doi:10.15181/ab.v15i1.28.

- ^ Šmitek, Zmago (5 May 2015). "The Image of the Real World and the World Beyond in the Slovene Folk TraditionPodoba sveta in onstranstva v slovenskem ljudskem izročilu". Studia mythologica Slavica. 2: 161. doi:10.3986/sms.v2i0.1848.

- ^ Eckert, Rainer (January 1998). "On the Cult of the Snake in Ancient Baltic and Slavic Tradition (based on language material from the Latvian folksongs)". Zeitschrift für Slawistik. 43 (1). doi:10.1524/slaw.1998.43.1.94. S2CID 171032008.

- ^ Hudec, Ivan. Mýty a báje starých Slovanů. [s.l.]: Slovart, 2004. S. 1994. ISBN 80-7145-111-8. (in Czech)

- ^ Gerasimenko, I. A.; Dmutrieva, J. L. (15 December 2015). "The Image of the World Tree in the Aspect of Russian Linguistic Culture". Russian Language Studies (4): 16–22.

- ^ Goshchytska, Tеtyana (21 June 2019). "The tree symbol in world mythologies and the mythology of the world tree (іllustrated by the example of the ukrainian Carpathians traditional culture)". The Ethnology Notebooks. 147 (3): 622–640. doi:10.15407/nz2019.03.622. S2CID 197854947.

- ^ Szyjewski, Andrzej (2003). Religia Słowian. Krakow: Wydawnictwo WAM. pp. 36-37. ISBN 83-7318-205-5. (in Polish)

- ^ Karpun, Mariia (30 November 2018). "Representations of the World Tree in traditional culture of Don Cossacks". Przegląd Wschodnioeuropejski. 9 (2): 115–122. doi:10.31648/pw.3088. S2CID 216841139.

- ^ Scholem, Gershom Gerhard (1990). Origins of the Kabbalah. Princeton University Press. ISBN 0691020477. Retrieved 1 May 2014 – via Google Books.

- ^ "The Treasury of Souls for Tree of Souls". Scribd. The Mythology of Judaism. Archived from the original on 30 October 2012. Retrieved 15 June 2015.

- ^ Marvin Meyer; Willis Barnstone (2009). "On the Origin of the World". The Gnostic Bible. Shambhala. Retrieved 2022-02-03.

- ^ Nasoraia, Brikha H.S. (2021). The Mandaean gnostic religion: worship practice and deep thought. New Delhi: Sterling. ISBN 978-81-950824-1-4. OCLC 1272858968.

- ^ Nasoraia, Brikha (2022). The Mandaean Rivers Scroll (Diwan Nahrawatha): an analysis. London: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-367-33544-1. OCLC 1295213206.

- ^ Martirosyan, Hrach (2018). "Armenian Andndayin ōj and Vedic Áhi- Budhnyà- "Abyssal Serpent"". In: Farnah: Indo-Iranian and Indo-European Studies. pp. 191–197.

- ^ "Religious Beliefs of the Caucasian Society of the Early Iron Age (According to Archaeological Evidence)". Gesellschaft und Kultur im alten Vorderasien. 1982. pp. 127–136. doi:10.1515/9783112320860-018. ISBN 9783112309674.

- ^ Gogiashvili, Elene (2013). "About Georgian Fairytales". Bulletin de l'Académie Belge pour l'Étude des Langues Anciennes et Orientales: 159–171. doi:10.14428/babelao.vol2.2013.19913.

- ^ Gogiashvili, Elene (2009). ფრინველისა და გველის ბრძოლის მითოლოგემა უძველეს გრაფიკულ გამოსახულებასა და ზეპირსიტყვიერებაში [The Myth about a Conflict Between a Bird and a Snake on the Old Graphics and in Folklore]. In: სჯანი [Sjani] nr. 10, pp. 146–156. (in Georgian)

- ^ Ünal, Ahmet. "Parts of Trees in Hittite According to a Medical Incantation Text (KUB 43, 62)". In: Hittite and Other Anatolian and Near Eastern Studies in Honour of Sedat Alp [Sedat Alp Festschrift]. Heinrich Otten, Ekrem Akurgal, Hayri Ertem, Aygül Süel (eds.). Ankara: TÜRK TARlH KURUMU BASIMEVl, 1992. p. 496.

- ^ Collins, B. J. (2002). "Animals in Hittite Literature". In: A History of the Animal World in the Ancient Near East. Leiden, The Netherlands: Brill. pp. 244–245. doi:10.1163/9789047400912_008

- ^ Melchert, H. Craig. "Hittite antaka- "loins" and an Overlooked Myth about Fire". In: Hittite Studies in Honor of Harry A. Hoffner Jr. on the Occasion of His 65th Birthday. Edited by Gary Beckman, Richard H. Beal and Gregory McMahon. University Park, US: Penn State University Press, 2003. pp. 284–285. doi:10.1515/9781575065434-025.

- ^ Winitzer, Abraham (2013). "Etana in Eden: New Light on the Mesopotamian and Biblical Tales in Their Semitic Context". Journal of the American Oriental Society. 133: 444–445. doi:10.7817/JAMERORIESOCI.133.3.0441..

- ^ Valk, Jonathan (2021). "The Eagle and the Snake, or Anzû and bašmu? Another Mythological Dimension in the Epic of Etana". Journal of the American Oriental Society. 140 (4): 889–900. doi:10.7817/jameroriesoci.140.4.0889. S2CID 230537775..

- ^ Rose, Jenny (2019). "Near Eastern and Old Iranian myths". In: Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Classics. doi:10.1093/acrefore/9780199381135.013.8150

- ^ Schmidt, Hanns-Peter (2002). "Simorgh". In: Encyclopedia Iranica.

- ^ Philpot, Mrs. J. H. (1897). The Sacred Tree; or the tree in religion and myth. London: MacMillan & Co. pp. 123–124.

- ^ Taheri, Sadreddin (2013). "Plant of life in Ancient Iran, Mesopotamia, and Egypt". Honarhay-e Ziba Journal. 18 (2). Tehran: 15.

- ^ Lechler, George (1937). "The Tree of Life in Indo-European and Islamic Cultures". Ars Islamica. 4: 369–419. JSTOR 25167048.

- ^ Shulman, David (1 January 1979). "Murukan, the mango and Ekāmbareśvara-Śiva: Fragments of a Tamil creation myth?". Indo-Iranian Journal. 21 (1): 27–40. JSTOR 24653474. S2CID 189767945.

- ^ M. Hoppál. "Shamanism and the Belief System of the Ancient Hungarians". In: Ethnographica et folkloristica carpathica 11 (1999): 59.

- ^ Sanjuán, Oscar Abenójar (2009). "El abedul de hojas doradas: representaciones y funciones del " Axis Mundi" en el folclore finougrio". Liburna (2): 13–24.

- ^ "The Tree Of Life In Turkic Communities With Its Current Effects". ULUKAYIN. 2021-10-03. Retrieved 2022-05-11.

- ^ Lyailya, Kaliakbarova (6 May 2018). "Spatial Orientations of Nomads' Lifestyle and Culture". Rupkatha Journal on Interdisciplinary Studies in Humanities. 10 (2). doi:10.21659/rupkatha.v10n2.03.

- ^ a b c Pavlova, Olga Ksenofontovna (30 September 2018). "Mythological Image in Olonkho of the North-Eastern Yakut Tradition: Sacred Tree". Journal of History Culture and Art Research. 7 (3): 79. doi:10.7596/taksad.v7i3.1720. S2CID 135257248.

- ^ a b Dochu, Alina (December 2017). "Turkic etymological background of the English bird name terek ' Tringa cinereus '" (PDF). Acta Orientalia Academiae Scientiarum Hungaricae. 70 (4): 479–483. doi:10.1556/062.2017.70.4.6. S2CID 134741505.

- ^ a b Zhernosenko, I. A.; Rogozina, I. V. "WORLDVIEW AND MENTALITY OF ALTAI'S INDIGENOUS INHABITANTS". In: Himalayan and Central Asian Studies; New Delhi Vol. 18, Ed. 3/4 (Jul–Dec 2014): 111.

- ^ Satanar, Marianna T. (25 December 2020). "К семиотической интерпретации мифологического образа древа Аал Луук мас в эпосе олонхо". Oriental Studies. 13 (4): 1135–1154. doi:10.22162/2619-0990-2020-50-4-1135-1154. S2CID 241597729.

- ^ a b ПОПОВА, Г. С. (2019). "ДРЕВО МИРА ААЛ ЛУУК МАС В СОВРЕМЕННОЙ КУЛЬТУРЕ ЯКУТОВ САХА". doi:10.24411/2071-6427-2019-00039.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Хисамитдинова, Ф.г. (2014). "Божества верхнего мира в мифологии башкир". Oriental Studies (4): 146–154.

- ^ Батыршин, Ш.ф. (2019). "Образы мифических животных в русской, башкирской и китайской лингвокультурах". Мир науки, культуры, образования. 2 (75): 470–472.

- ^ Равиловна, Хусаинова Гульнур (2012). "Отражение мифологических воззрений в башкирской волшебной сказке". Вестник Челябинского государственного университета. 32 (286): 126–129.

- ^ Хисамитдинова, Ф.г. (2014). "Божества верхнего мира в мифологии башкир". Oriental Studies (4): 146–154.

- ^ Kaskabasov, Seit (2018). "Iranian Folk Motifs And Religious Images In Kazakh Literature And Folklore". Astra Salvensis. VI (Sup. 1): 423–432.

- ^ Znamenski, Andrei A. (2003). "Siberian Shamanism in Soviet Imagination". Shamanism in Siberia. pp. 131–278. doi:10.1007/978-94-017-0277-5_3. ISBN 978-90-481-6484-4.

- ^ a b Holmberg, Uno (1927). Finno-Ugric and Siberian. The Mythology of All Races Vol. 4. Boston: Marshall Jones Company. 1927. p. 357.

- ^ Yang, Lihui; An, Deming. Handbook of Chinese Mythology. ABC-Clio. 2005. pp. 117–118, 262. ISBN 1-57607-807-8.

- ^ Yang, Lihui; An, Deming. Handbook of Chinese Mythology. ABC-Clio. 2005. pp. 32, 66, 91, 95, 117–118, 212, 215–216, 231. ISBN 1-57607-807-8.

- ^ Penprase, Bryan E. The Power of Stars. Springer, 2017. p. 146. ISBN 978-3-319-52597-6.

- ^ Leeming, David Adams. Creation Myths of the World: An Encyclopedia. Second Edition. Volume I: Parts I-II. ABC-Clio. 2010. p. 273. ISBN 978-1-59884-175-6.

- ^ Radulović, Nemanja. "Arbor Mundi: Visual Formula and the Poetics of Genre". In: Epic Formula: a Balkan Perspective. Edited by Mirjana Detelić and Lidija Delić. Belgrade: Institute for Balkan Studies/Serbian Academy of Sciences and Arts. 2015. p. 67. ISBN 978-86-7179-091-8.

- ^ Levin, Isidor (January 1966). "Etana. Die keilschriftlichen Belege einer Erzählung". Fabula. 8 (Jahresband): 1–63. doi:10.1515/fabl.1966.8.1.1. S2CID 161315794.

- ^ Мeдан, Маја Ј. (2017). "'Од немила до недрага' Милана Дединца: есејизација лирске прозе или лиризација есеја". Есеј, есејисти и есејизација у српској књижевности ; Форме приповедања у српској књижевности. Научни састанак слависта у Вукове дане. Vol. 46/2. pp. 185–194. doi:10.18485/msc.2017.46.2.ch20. ISBN 978-86-6153-470-6.

- ^ Vukicevic, Dragana. "БОГ КОЈИ ОДУСТАЈЕ (Илија Вукићевић Прича о селу Врачима и Сими Ступици и Радоје Домановић Краљевић Марко по други пут међу Србима)" [The Resigning God]. In: СРПСКИ ЈЕЗИК, КЊИЖЕВНОСТ, УМЕТНОСТ. Зборник радова са VI међународног научног скупа одржаног на Филолошко-уметничком факултету у Крагујевцу (28–29. X 2011). Књига II: БОГ. Крагујевац, 2012. p. 231.

- ^ Sofrić, Pavle (1990). Glavnije bilje u narodnom verovanju i pevanju kod nas Srba (in Serbian). BIGZ. pp. 119–121. ISBN 9788613004745.

- ^ Benovska-Sabkova, Milena. ""Тримата братя и златната ябълка" — анализ на митологическата семантика в сравнителен балкански план ["The three brothers and the golden apple": Analysis of the mythological semantic in comparative Balkan aspect]. In: "Българска етнология" [Bulgarian Ethnology] nr. 1 (1995): 90–102.

- ^ a b Bárdos József. "Világ és más(ik) világok tündérmesékben" [Worlds and Other Worlds in Fairy Tales]. In: Gradus Vol. 2, No 1 (2015). p. 16. ISSN 2064-8014.

- ^ Uther, Hans-Jörg. The types of International Folktales. A Classification and Bibliography, Based on the System of Antti Aarne and Stith Thompson. Folklore Fellows Communications (FFC) n. 284. Helsinki: Suomalainen Tiedeakatemia-Academia Scientiarum Fennica, 2004. p. 177.

- ^ Tacha, Athena. Brancusi's Birds. New York University Press for the College Art Association of America. 1969. p. 8. ISBN 9780814703953.

- ^ BLAŽEK, Václav. "The Role of "Apple" in the Indo-European Mythological Tradition and in Neighboring Traditions". In: Lisiecki, Marcin; Milne, Louise S.; Yanchevskaya, Nataliya. Power and Speech: Mythology of the Social and the Sacred. Toruń: EIKON, 2016. pp. 257–297. ISBN 978-83-64869-16-7.

- ^ BLAŽEK, Václav. "The Role of "Apple" in the Indo-European Mythological Tradition and in Neighboring Traditions". In: Lisiecki, Marcin; Milne, Louise S.; Yanchevskaya, Nataliya. Power and Speech: Mythology of the Social and the Sacred. Toruń: EIKON, 2016. p. 184. ISBN 978-83-64869-16-7.

- ^ Beza, M. (1925). "The Sacred Marriage in Roumanian Folklore". The Slavonic Review. 4 (11): 321–333. JSTOR 4201965.

Literature

edit- David Abram. The Spell of the Sensuous: Perception and Language in a More-Than-Human World, Vintage, 1997

- Burkert W (1996). Creation of the Sacred: Tracks of Biology in Early Religions. Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-17570-9.

- Haycock DE (2011). Being and Perceiving. Manupod Press. ISBN 978-0-9569621-0-2.

- Miller, Mary Ellen; Taube, Karl A. (1993). The Gods and Symbols of Ancient Mexico and the Maya: An Illustrated Dictionary of Mesoamerican Religion. Thames and Hudson. ISBN 978-0-500-05068-2.

- Roys, Ralph L., The Book of Chilam Balam of Chumayel. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press 1967.

Further reading

edit- Balalaeva, O.; Pluzhnikov, N.; Funk, D.; Batyanova, E.; Dybo, A.; Bulgakova, T.; Burykin, A. (June 2019). "The Myth of the World Tree in the Shamanism of Siberian Peoples. Comments: Funk, D. A. In Search of the World Tree: Some Thoughts on What, Where, and How We Search [V poiskakh Mirovogo dreva: razmyshleniia o tom, chto, gde i kak my ishchem]; Batyanova, E. P. Trees, Shamans, and Other Worlds [Derev'ia, shamany i inye miry]; Dybo, A. V. The World Tree: Data from Siberian Languages [Mirovoe drevo: dannye sibirskikh yazykov]; Bulgakova, T. D. The "World Tree" in the Shamanic Image of the World among the Nanai ["Mirovoe drevo" v shamanskoi kartine mira nanaitsev]; Burykin, A. A. The "Shamanic Theater" and Its Attributes ["Shamanskii teatr" i ego atributy]; Balalaeva, O. E., and N. V. Pluzhnikov. Response to Commenters: Thinking about the Use of Discussions (One of the Keys) [Otvet opponentam: razmyshleniia o pol'ze diskussii (odin iz kliuchei)]". Etnograficheskoe Obozrenie (3): 80–122. doi:10.31857/S086954150005293-2.

- Bauks, Michaela (6 May 2012). "Sacred Trees in the Garden of Eden and Their Ancient Near Eastern Precursors". Journal of Ancient Judaism. 3 (3): 267–301. doi:10.30965/21967954-00303001.

- Butterworth, E. A. S. The Tree - the Navel of the Earth. Berlin: de Gruyter, 1970.

- Holmberg, Uno. Der Baum des Lebens (= Suomalaisen Tiedeakatemian toimituksia. Sarja B = Series B, 16, 3, ISSN 0066-2011). Suomalainen Tiedeakatemia, Helsinki, 1922 (Auch: Edition Amalia, Bern 1996, ISBN 3-9520764-2-2).

External links

edit- Cosmology of the Ancient Balts by Vytautas Straižys and Libertas Klimka (Lithuanian.net)