The Atari 8-bit computers, formally launched as the Atari Home Computer System,[4] are a series of home computers introduced by Atari, Inc., in 1979 with the Atari 400 and Atari 800.[5] The architecture is designed around the 8-bit MOS Technology 6502 CPU and three custom coprocessors which provide support for sprites, smooth multidirectional scrolling, four channels of audio, and other features. The graphics and sound are more advanced than most of its contemporaries, and video games are a key part of the software library. The 1980 first-person space combat simulator Star Raiders is considered the platform's killer app.

The Atari 800's nameplate is on the dual-width cartridge slot cover. | |

| Manufacturer |

|

|---|---|

| Type | Home computer |

| Release date | November 1979[1][2] |

| Introductory price |

|

| Discontinued | January 1, 1992 |

| Units sold | 4 million[citation needed] |

| Operating system | Custom Atari DOS (optional) |

| CPU | MOS Technology 6502B or MOS Technology 6502 SALLY |

| Graphics | 384 pixels per TV line, 256 colors, 8 × sprites, raster interrupts |

| Sound | 4 × oscillators with noise mixing or 2 × AM digital |

| Connectivity |

|

| Successor | Atari ST |

| Related | Atari 5200 |

The Atari 800 was positioned as a high-end model and the 400 as more affordable. The 400 has a pressure-sensitive, spillproof membrane keyboard and initially shipped with a non-upgradable 8 KB of RAM. The 800 has a conventional keyboard, a second cartridge slot, and allows easy RAM upgrades to 48K. Both use identical 6502 CPUs at 1.79 MHz (1.77 MHz for PAL versions) and coprocessors ANTIC, POKEY, and CTIA/GTIA. The plug-and-play peripherals use the Atari SIO serial bus, and one of the SIO developers eventually went on to co-patent USB (Universal Serial Bus).[6] The core architecture of the Atari 8-bit computers was reused in the 1982 Atari 5200 game console, but games for the two systems are incompatible.

The 400 and 800 were replaced by multiple computers with the same technology and different presentation. The 1200XL was released in early 1983 to supplant the 800. It was discontinued months later, but the industrial design carried over to the 600XL and 800XL released later the same year. After the company was sold and reestablished, Atari Corporation released the 65XE (sold as the 800XE in some European markets) and 130XE in 1985. The XL and XE are lighter in construction, have two joystick ports instead of four, and Atari BASIC is built-in. The 130XE has 128 KB of bank-switched RAM. In 1987, after the Nintendo Entertainment System reignited the console market, Atari Corporation packaged the 65XE as a game console, with an optional keyboard, as the Atari XEGS. It is compatible with 8-bit computer software and peripherals.

The 8-bit computers were sold both in computer stores and department stores such as Sears using a demo to attract customers.[7] Two million Atari 8-bit computers were sold during its major production run between late 1979 and mid-1985.[8][9] The primary global competition came when the similarly equipped Commodore 64 was introduced in 1982. In 1992, Atari Corporation officially dropped all remaining support for the 8-bit line.[10]

History

editDesign of the "Home Computer System" started at Atari as soon as the Atari Video Computer System was released in late 1977. While designing the VCS in 1976, the engineering team from Atari Grass Valley Research Center (originally Cyan Engineering)[11] said the system would have a three-year lifespan before becoming obsolete. They started blue sky designs for a new console that would be ready to replace it around 1979.[12]

They developed essentially a greatly updated version of the VCS, fixing its major limitations but sharing a similar design philosophy.[12] The newer design has better speed, graphics, and sound. Work on the chips for the new system continued throughout 1978 and focused on much-improved video coprocessor known as the CTIA (the VCS version was the TIA).[13]

During the early development period, the home computer era began in earnest with the TRS-80, PET, and Apple II—what Byte magazine dubbed the "1977 Trinity".[14] Nolan Bushnell sold Atari to Warner Communications for US$28 million in 1976 to fund the launch of the VCS.[15] In 1978, Warner hired Ray Kassar to become the CEO of Atari. Kassar said the chipset should be used in a home computer to challenge Apple.[6] To adapt the machine to this role, it needed character graphics, some form of expansion for peripherals, and run the then-universal BASIC programming language.[12]

The VCS lacks bitmap graphics and a character generator. All on-screen graphics are created using sprites and a simple background generated by data loaded by the CPU into single-scan-line video registers. Atari engineer Jay Miner architected the two video chips for the Atari 8-bit computers. The CTIA chip includes sprites and background graphics, but to reduce load on the main CPU, loading video registers and buffers is delegated to a dedicated microprocessor, the Alphanumeric Television Interface Controller or ANTIC. CTIA and ANTIC work together to produce a complete display, with ANTIC fetching scan line data from a framebuffer and sprite memory in RAM, plus character set bitmaps for character modes, and feeding these to the CTIA. CTIA processes the sprite and playfield data in the light of its own color, sprite, and graphics registers to produce the final color video output.[16]

The resulting system was far in advance of anything then available on the market. Commodore was developing a video driver at the time, but Chuck Peddle, lead designer of the MOS Technology 6502 CPU used in the VCS and the new machines, saw the Atari work during a visit to Grass Valley. He realized the Commodore design would not be competitive but he was under a strict non-disclosure agreement with Atari, and was unable to tell anyone at Commodore to give up on their own design. Peddle later commented that "the thing that Jay did, just kicked everybody's butt."[17]

Development

editManagement identified two sweet spots for the new computers: a low-end version known internally as "Candy", and a higher-end machine known as "Colleen" (named after two Atari secretaries).[18] Atari would market Colleen as a computer and Candy as a game machine or hybrid game console. Colleen includes user-accessible expansion slots for RAM and ROM, two 8 KB ROM cartridge slots, RF and monitor output (including two pins for separate luma and chroma suitable for superior S-Video output) and a full keyboard. Candy was initially designed as a game console, lacking a keyboard and input/output ports, although an external keyboard was planned for joystick ports 3 and 4. At the time, plans called for both to have a separate audio port supporting cassette tapes as a storage medium.[19]

A goal for the new systems was user-friendliness. One executive stated, "Does the end user care about the architecture of the machine? The answer is no. 'What will it do for me?' That's his major concern. ... why try to scare the consumer off by making it so he or she has to have a double E or be a computer programmer to utilize the full capabilities of a personal computer?" For example, cartridges were expected to make the computers easier to use.[20] To minimize handling of bare circuit boards or chips, as is common with other systems of that period, the computers were designed with enclosed modules for memory, ROM cartridges, with keyed connectors to prevent them being plugged into the wrong slot. The operating system boots automatically, loading drivers from devices on the serial bus (SIO). The disk operating system for managing floppy storage was menu-driven. When no software is loaded, rather than leaving the user at a blank screen or machine language monitor, the OS goes to the "Memo Pad" which is a built-in full-screen editor without file storage support.[16]

As the design process for the new machines continued, there were questions about what the Candy should be. There was a running argument about whether the keyboard would be external or built-in.[21] By the summer of 1978, education had become a focus for the new systems. The Colleen design was largely complete by May 1978, but in early 1979 the decision was made that Candy would also be a complete computer, but intended for children. As such, it would feature a new keyboard designed to be resistant to liquid spills.[22]

Atari intended to port Microsoft BASIC to the machine as an 8 KB ROM cartridge. However, the existing 6502 version from Microsoft was around 7,900 bytes, leaving no room for extensions for graphics and sound. The company contracted with local consulting firm Shepardson Microsystems to complete the port. They recommended writing a new version from scratch, resulting in Atari BASIC.[23]

FCC issues

editTelevisions of the time normally had only one signal input, which was the antenna connection on the back. For devices like a computer, the video is generated and then sent to an RF modulator to convert it to antenna-like output. The introduction of many game consoles during this era had led to situations where poorly designed modulators would generate so much signal as to cause interference with other nearby televisions, even in neighboring houses. In response to complaints, the Federal Communications Commission (FCC) introduced new testing standards which are extremely exacting and difficult to meet.[24]

Other manufacturers avoided the problem by using built-in composite monitors, such as the Commodore PET and TRS-80. The TRS-80 has a slightly modified black and white television as a monitor. It was notorious for causing interference, and production was canceled when the more stringent FCC requirements came into effect on January 1, 1981. Apple Computer famously left off the modulator and sold them under a third party company as the Sup'R'Mod so they did not have to be tested.[25]

In a July 1977 visit with the engineering staff, a Texas Instruments (TI) salesman presented a new possibility in the form of an inexpensive fiber-optic cable with built-in transceivers. During the meeting, Joe Decuir proposed placing an RF modulator on one end, thereby completely isolating any electrical signals so that the computer would have no RF components. This would mean the computer would not have to meet the FCC requirements, yet users could still attach a television simply by plugging it in. His manager, Wade Tuma, later refused the idea saying "The FCC would never let us get away with that stunt." Unknown to Atari, TI used Decuir's idea. As Tuma had predicted, the FCC rejected the design, delaying that machine's release. TI ultimately shipped early machines with a custom television as the testing process dragged on.[24]

To meet the off-the-shelf requirement while including internal TV circuitry, the new machines needed to be heavily shielded. Both were built around very strong cast aluminum shields forming a partial Faraday cage, with the various components screwed down onto this internal framework. This resulted in an extremely sturdy computer, at the disadvantage of added manufacturing expense and complexity.[6]

The FCC ruling also made it difficult to have any sizable holes in the case, which would allow RF leakage. This eliminated expansion slots or cards that communicated with the outside world via their own connectors. Instead, Atari designed the Serial Input/Output (SIO) computer bus, a system for daisy-chaining multiple, auto-configuring devices to the computer through a single shielded connector. The internal slots were reserved for ROM and RAM modules; they did not have the control lines necessary for a fully functional expansion card, nor room to route a cable outside the case to communicate with external devices.[6]

400 and 800 release

editAfter Atari announced its intent to enter the home computer market in December 1978,[26] the Atari 400 and Atari 800 were presented at the Winter CES in January 1979[27] and shipped in November 1979.[1][2]

The names originally referred to the amount of memory: 4 KB RAM in the 400 and 8 KB in the 800. By the time they were released, RAM prices had started to fall, so the machines were both released with 8 KB, using 4kx1 DRAMs. The user-installable RAM modules in the 800 initially had plastic casings but this caused overheating issues, so the casings were removed. Later, the expansion cover was held down with screws instead of the easier-to-open plastic latches.[28] The computers eventually shipped with maxed-out RAM: 16k and 48k, respectively, using 16kx1 DRAMs.

Both models have four joystick ports, permitting four simultaneous players, but only a few games (such as M.U.L.E.) use them all. Paddle controllers are wired in pairs, and Super Breakout supports eight players.[29] The Atari 400, with a membrane keyboard and single internal ROM slot, outsold the Atari 800 by a 2-to-1 margin.[8] Only one cartridge for the 800's right slot was produced by March 1983, and later machines in the series have only one slot.[30][29]

Creative Computing mentioned the Atari machines in an April 1979 overview of the CES show. Calling Atari "the videogame people", it stated they came with "some fantastic educational, entertainment and home applications software".[31] In an August 1979 interview Atari's Peter Rosenthal suggested that demand might be low until the 1980–81 time frame, when he predicted about one million home computers being sold.[32] The April 1980 issue compared the machines with the Commodore PET, focused mostly on the BASIC dialects.[33] Ted Nelson reviewed the computer in the magazine in June 1980, calling it "an extraordinary graphics box". Describing his and a friend's "shouting and cheering and clapping" during a demo of Star Raiders, Nelson wrote that he was so impressed that "I've been in computer graphics for twenty years, and I lay awake night after night trying to understand how the Atari machine did what it did". He described the machine as "something else" but criticized the company for a lack of developer documentation. He concluded by stating "The Atari is like the human body – a terrific machine, but (a) they won't give you access to the documentation, and (b) I'd sure like to meet the guy that designed it".[34] Kilobaud Microcomputing wrote in September 1980 that the Atari 800 "looks deceptively like a video game machine, [but had] the strongest and tightest chassis I have seen since Raquel Welch. It weighs about ten pounds ... The large amount of engineering and design in the physical part of the system is evident". The reviewer praised the documentation as "show[ing] the way manuals should be done", and the "excellent 'feel'" of the keyboard.[35] InfoWorld favorably reviewed the 800's performance, graphics, and ROM cartridges, but disliked the documentation and cautioned that the unusual right Shift key location might make the computer "unsuitable for serious word processing". There is an "Atari key" between the / and shift, whereas a typical keyboard would extend the shift key into this area. Noting that the amount of software and hardware available for the computer "is no match for that of the Apple II or the TRS-80", the magazine concluded that the 800 "is an impressive machine that has not yet reached its full computing potential".[36]

Sweet/Liz project

editThough planning an extensive advertising campaign for 1980,[20] Atari found difficult competition from Commodore, Apple, and Tandy. By mid-1981, it had reportedly lost $10 million on sales of $10–13 million from more than 50,000 computers.[37][38]

In 1982, Atari started the Sweet 8 (or Liz NY) and Sweet 16 projects to create an upgraded set of machines that were easier to build and less costly to produce. Atari ordered a custom 6502, initially labelled 6502C, but eventually known as SALLY to differentiate it from a standard 6502C. A 6502C was simply a version of the 6502 able to run up to 4 MHz. The A models run at 1, and the B's at 2. The basis for SALLY is a 6502B. SALLY was incorporated into late-production 400 and 800 models, all XL/XE models, and the Atari 5200 and Atari 7800 consoles. SALLY adds logic to disable the clock signal, called HALT, which ANTIC uses to shut off the CPU to access the data/address bus.[39]

Mirroring the 400/800, two systems were planned, the 1000 with 16 KB and the 1000X with 64 KB, each expandable via a Parallel Bus Interface slot on the back of the machine.

1200XL

editThe original Sweet 8/16 plans were dropped and only one machine using the new design was released. Announced at a New York City press conference on December 13, 1982,[40][41] the 1200XL was presented at the Winter CES on January 6–9, 1983.[42] It shipped in March[citation needed] 1983[43] with 64 KB of RAM, built-in self test, a redesigned keyboard (with four function keys and a HELP key), and redesigned cable port layout.[30] The number of joystick ports was reduced from 4 to 2. There is no PAL version of the 1200XL.[citation needed]

Announced at a retail price of $1000,[44] the 1200XL was released at $899 (equivalent to about $2,800 in 2023).[42] This is $100 less than the announced price of the Atari 800 at its release in 1979,[3] but by this time the 800 was priced much lower.

The system uses the SIO port again instead of the Parallel Bus Interface. The +12V pin in the SIO port is not connected, which prevents a few devices from working. The +12V was typically used to power RS-232 devices, which now required an external power source. An improved video circuit provides more chroma for a more colorful image, but the chroma line is not connected to the monitor port, the only place that could make use of it. The operating system has compatibility problems with some older software.

The 1200XL was discontinued in June 1983.

Compute! stated in an early 1983 editorial that the 1200XL was too expensive;[45] John J. Anderson of Creative Computing agreed.[46] Bill Wilkinson, author of Atari BASIC, co-founder of Optimized Systems Software, and columnist for Compute!, criticized the computer's features and price. He wrote that the 1200XL was a "terrific bargain" if sold for less than $450, but that if it cost more than the 800, "buy an 800 quick!"[47]

600XL and 800XL

editIn May 1981, the Atari 800's price was $1,050 (equivalent to $3,500 in 2023),[36] but by mid-1983, because of price wars in the industry, it was $165 (equivalent to $500 in 2023)[48] and the 400 was under $150 (equivalent to $460 in 2023).[44] The 1200XL was a flop, and the earlier machines were too expensive to produce to be able to compete at the rapidly falling price points.[citation needed]

A new lineup was announced at the 1983 Summer CES, closely following the original Sweet concepts. The 600XL is essentially the Liz NY model and the spiritual successor of the 400, and the 800XL would replace both the 800 and 1200XL. The machines follow the styling of the 1200XL but are smaller from back to front, and the 600XL is more so.

Atari had difficulty in transitioning manufacturing to Asia after closing its US factory.[49] Originally intended to replace the 1200XL in mid-1983, the new models did not arrive until late that year. Although the 600XL/800XL were well positioned in terms of price and features, during the critical Christmas season they were available only in small numbers while the Commodore 64 was widely available.[8] Brian Moriarty stated in ANALOG Computing that Atari "fail[ed] to keep up with Christmas orders for the 600 and 800XLs", reporting that as of late November 1983 the 800XL had not appeared in Massachusetts stores while 600XL "quantities are so limited that it's almost impossible to obtain".[50]

After losing $563 million in the first nine months of the year, Atari that month announced that prices would rise in January, stating that it "has no intention of participating in these suicidal price wars."[51] The 600XL and 800XL's prices in early 1984 were $50 higher than for the VIC-20 and Commodore 64.[52]

ANALOG Computing, writing about the 600XL in January 1984, stated that "the Commodore 64 and Tandy CoCo look like toys by comparison." The magazine approved of its not using the 1200XL's keyboard layout, and predicted that the XL's parallel bus "actually makes the 600 more expandable than a 400 or 800." While disapproving of the use of an operating system closer to the 1200XL's than the 400 and 800's, and the "inadequate and frankly disappointing" documentation, ANALOG concluded that "our first impression ... is mixed but mostly optimistic." The magazine warned, however, that because of "Atari's sluggish marketing", unless existing customers persuaded others to buy the XL models, "we'll all end up marching to the beat of a drummer whose initials are IBM."[50]

Unreleased XL models

editThe high-end 1400XL and 1450XLD were announced alongside the 600XL and 800XL. They added a built-in 300 baud modem and a voice synthesizer, and the 1450XLD has a built-in double-sided floppy disk drive in an enlarged case, with a slot for a second drive. Atari BASIC is built into the ROM and the PBI at the back for external expansion.

The 1400XL and the 1450XLD had their delivery dates pushed back, and in the end, the 1400XL was canceled outright, and the 1450XLD so delayed that it would never ship. Other prototypes which never reached market include the 1600XL, 1650XLD, and 1850XLD. The 1600XL was to have been a dual-processor model capable of running 6502 and 80186 code, and the 1650XLD is a similar machine in the 1450XLD case. These were canceled when James J. Morgan became CEO and wanted Atari to return to its video game roots.[53] The 1850XLD was to have been based on the Lorraine chipset[54] which became the Amiga.

Tramiel takeover, declining market

editCommodore founder Jack Tramiel resigned in January 1984 and in July, he purchased the Atari consumer division from Warner for an extremely low price. No cash was required, and instead Warner had the right to purchase $240 million in long-term notes and warrants, and Tramiel had an option to buy up to $100 million in Warner stock. When Tramiel took over, the high-end XL models were canceled and the low-end XLs were redesigned into the XE series. Nearly all research, design, and prototype projects were canceled, including the Amiga-based 1850XLD. Tramiel focused on developing the 68000-based Atari ST computer line and recruiting former Commodore engineers to work on it.

Atari sold about 700,000 computers in 1984 compared to Commodore's two million.[55] As his new company prepared to ship the Atari ST in 1985, Tramiel stated that sales of Atari 8-bit computers were "very, very slow".[56] They were never an important part of Atari's business compared to video games, and it is possible that the 8-bit line was never profitable for the company though almost 1.5 million computers had been sold by early 1986.[37][57][58][48]

By that year, the Atari software market was decreasing in size. Antic magazine stated in May 1985 that it had received many letters complaining that software companies were ignoring the Atari market, and urged readers to contact the companies' leaders.[59] "The Atari 800 computer has been in existence since 1979. Six years is a pretty long time for a computer to last. Unfortunately, its age is starting to show", ANALOG Computing wrote in February 1986. The magazine stated that while its software library was comparable in size to that of other computers, "now—and even more so in the future—there is going to be less software being made for the Atari 8-bit computers", warning that 1985 only saw a "trickle" of major new titles and that 1986 "will be even leaner".[60]

Computer Gaming World that month stated "games don't come out for the Atari first anymore".[61] In April, the magazine published a survey of ten game publishers which found that they planned to release 19 Atari games in 1986, compared to 43 for Commodore 64, 48 for Apple II, 31 for IBM PC, 20 for Atari ST, and 24 for Amiga. Companies stated that one reason for not publishing for Atari was the unusually high amount of software piracy on the computer, partly caused by the Happy Drive.[62][63][64] The magazine warned later that year, "Is this the end for Atari 800 games? It certainly looks like it might be from where I write".[63] In 1987, MicroProse confirmed that it would not release Gunship for the Atari 8-bits, stating that the market was too small.[65]

XE series

editThe 65XE and 130XE (XE stands for XL-Compatible Eight-bit)[66] were announced in 1985 at the same time as the Atari 520ST, and they visually resemble the ST. The 65XE has 64 KB of RAM and is functionally equivalent to the 800XL minus the PBI connection. The 130XE has 128 KB of memory, accessible through bank switching. The additional 64K can be used as a RAM drive.

The 130XE includes the Enhanced Cartridge Interface (ECI), which is almost compatible with the Parallel Bus Interface, but physically smaller and located next to the standard 400 and 800 compatible cartridge slot. It provides only those signals that do not exist in the latter. ECI peripherals were expected to plug into both the standard Cartridge Interface and the ECI port. Later revisions of the 65XE contain the ECI port.

The 65XE was sold as the 800XE in Germany and Czechoslovakia[67] to ride on the popularity of the 800XL in those markets. All 800XE units contain the ECI port.[68]

XE Game System

editThe Atari XEGS (XE Game System) was launched in 1987. A repackaged 65XE with a removable keyboard, it boots to the 1981 port of Missile Command instead of BASIC if the keyboard is disconnected.

Design

editThe Atari machines consist of a 6502 as the main processor, a combination of ANTIC and GTIA chips to provide graphics, and the POKEY chip to handle sound and serial input/output. These support chips are controlled via a series of registers that can be user-controlled via memory load/store instructions running on the 6502. For example, the GTIA uses a series of registers to select colors for the screen; these colors can be changed by inserting the correct values into its registers, which are mapped into the address space that is visible to the 6502. Some of the coprocessors use data stored in RAM, such as ANTIC's display buffer and display list, and GTIA's Player/Missile (sprite) information.

The custom hardware features enable the computers to perform many functions directly in hardware, such as smooth background scrolling, that would need to be done in software in most other computers. Graphics and sound demos were part of Atari's earliest developer information and used as marketing materials with computers running in-store demos.[61]

ANTIC

editANTIC is a microprocessor which processes a sequence of instructions known as a display list. An instruction adds one row of the specified graphics mode to the display. Each mode varies based on whether it represents text or a bitmap, the resolution and number of colors, and its vertical height in scan lines. An instruction also indicates if it contains an interrupt, if fine scrolling is enabled, and optionally where to fetch the display data from memory.[69]

Since each row can be specified individually, the programmer can create displays containing different text or bitmapped graphics modes on one screen, where the data can be fetched from arbitrary, non-sequential memory addresses.[70]

ANTIC reads this display list and the display data using DMA (Direct Memory Access), then translates the result into a pixel data stream representing the playfield text and graphics. This stream then passes to GTIA which applies the playfield colors and incorporates Player/Missile graphics (sprites) for final output to a TV or composite monitor. Once the display list is set up, the display is generated without any CPU intervention.

There are 15 character and bitmap modes. In low-resolution modes, 2 or 4 colors per display line can be set. In high-resolution mode, one color can be set per line, but the luminance values of the foreground and background can be adjusted. High resolution bitmap mode (320x192 graphics) produces NTSC composite artifact colors; these colors do not occur on PAL machines.

For text modes, the character set data is pointed to by a register. It defaults to an address in ROM, but if pointed to RAM then a programmer can create custom characters. Depending on the text mode, this data can be on any 1K or 512 byte boundary. Additional registers flip all characters upside down and toggle inverse video.

The ANTIC chip allows a variety of Playfield modes and widths, and the original Atari Operating System included with the Atari 800/400 computers provides easy access to a subset of these graphics modes. These are exposed to users through Atari BASIC via the "GRAPHICS" command and to some other languages via similar system calls. The later version of the OS used in the XL/XE computers added support for most of these "missing" graphics modes.

ANTIC text modes support soft, redefineable character sets. ANTIC has four different methods of glyph rendering related to the text modes: Normal, Descenders, Single color character matrix, and Multiple colors per character matrix.

The ANTIC chip uses a display list and other settings to create these modes. Any graphics mode in the default CTIA/GTIA color interpretation can be freely mixed without CPU intervention by changing instructions in the display list.

The actual ANTIC screen geometry is not fixed. The hardware can be directed to display a narrow Playfield (128 color clocks/256 hi-res pixels wide), the normal width Playfield (160 color clocks/320 hi-res pixels wide), and a wide, overscan Playfield (192 color clocks/384 hi-res pixels wide) by setting a register value. The operating system's default height for creating graphics modes is 192 scan lines, and ANTIC can display vertical overscan up to 240 TV scan lines tall by creating a custom display list.

The display list capabilities provide horizontal and vertical coarse scrolling requiring minimal CPU direction. Furthermore, the ANTIC hardware supports horizontal and vertical fine scrolling—shifting the display of screen data incrementally by single pixels (color clocks) horizontally and single scan lines vertically.

The system CPU clock and video hardware are synchronized to one-half the NTSC clock frequency. Consequently, the pixel output of all display modes is based on the size of the NTSC color clock which is the minimum size needed to guarantee correct and consistent color regardless of the pixel location on the screen. The fundamental accuracy of the pixel color output allows horizontal fine scrolling without color "strobing"—unsightly hue changes in pixels based on horizontal position caused when signal timing does not provide the TV/monitor hardware adequate time to reach the correct color.

CTIA/GTIA

editThe Color Television Interface Adaptor[71] (CTIA) is the graphics chip originally used in the Atari 400 and 800. It is the successor to the TIA chip of the 1977 Atari VCS. According to Joe Decuir, George McLeod designed the CTIA in 1977. It was replaced with the Graphic Television Interface Adaptor[71] (GTIA) in later revisions of the 400 and 800 and all later 8-bit models. GTIA, also designed by McLeod, adds three new playfield graphics modes to ANTIC which enable more colors.[39]

The CTIA/GTIA receives Playfield graphics information from ANTIC and applies colors to the pixels from a 128 or 256 color palette depending on the color interpretation mode in effect. CTIA/GTIA controls Player/Missile Graphics (sprites) including collision detection between players, missiles, and the playfield; display priority for objects; and color/luminance control of all displayed objects. CTIA/GTIA outputs separate digital luminance and chroma signals, which are mixed to form an analog composite video signal.

CTIA/GTIA reads the joystick triggers and the Option, Select and Start keys, and controls the keyboard speaker in the Atari 400 and 800. In later computer models the audio output for the keyboard speaker is mixed with the audio out for transmission to the TV/video monitor.

POKEY

editPOKEY is a custom chip used for reading the keyboard, generating sound and serial communications (in conjunction with the Peripheral Interface Adapter chip) commands and IRQs, plus controlling the 4 joystick movements on the 400 and 800 models, and later RAM banks or ROM (OS/BASIC/Self-test) enables for XL/XE lines.[72] It provides timers, a random number generator for generating acoustic noise and random numbers, and maskable interrupts. POKEY has four semi-independent audio channels, each with its own frequency, noise and volume control. Each 8-bit channel has its own audio control register which select the noise content and volume. For higher sound frequency resolution (quality), two of the audio channels can be combined for more accurate sound (frequency can be defined with 16-bit value instead of usual 8-bit). The name POKEY comes from the words "POtentiometer" and "KEYboard", which are two of the I/O devices that POKEY interfaces with (the potentiometer is the mechanism used by the paddle). The POKEY chip—and its dual- and quad-core versions—was used in many Atari coin-op arcade machines of the 1980s, including Centipede and Millipede,[73] Missile Command, Asteroids Deluxe, Major Havoc, and Return of the Jedi.

Models

editAtari, Inc. shipped three updated versions of the 400/800 using the same chipset and with a different case aesthetic: the short-lived 1200XL, then the 600XL and 800XL. Numerous other, wide-ranging projects to develop successors to the 8-bit line were cancelled. After the re-establishment of Atari as Atari Corporation, three more systems were released using largely the same technology as earlier machines: the 65XE and 128 KB 130XE in 1985, and finally the game console inspired Atari XEGS in 1987.

- 400 and 800 (1979) – original machines in beige cases. Both have 4 joystick ports below the keyboard and a cartridge slot covered by a door on the top of the machine. The 400 has a membrane keyboard. The 800 has full-travel keys, a second, rarely used, cartridge slot, and monitor output. Both have expandable memory (up to 48 KB); the RAM slots are easily accessible in the 800. Later PAL versions have the 6502C processor.

- 1200XL (1983) – new aluminum and smoked plastic case. Includes 64 KB of RAM, two joystick ports, a Help key, and four function keys. Some older software was incompatible with the new OS. Starting with the 1200XL, the single cartridge slot is on the side of the case, and there are only 2 joystick ports.

- 600XL and 800XL (1983) – the 600XL has 16 KB of memory and PAL versions have a monitor port. The 800XL has 64 KB and monitor output. Both have built-in BASIC and a Parallel Bus Interface (PBI) expansion port. The last produced PAL units contain the Atari FREDDIE chip and Atari BASIC revision C.

- 65XE and 130XE (1985) – the 130XE has 128 KB of bank-switched RAM and an Enhanced Cartridge Interface (ECI) instead of a PBI. The first revisions of the 65XE have no ECI or PBI, and the later ones contain the ECI. The 65XE was relabelled as 800XE in some European markets, and was mostly sold in West Germany, Austria and Switzerland.[68]

- XE Game System (1987) – a 65XE styled as a game console. The basic version of the system shipped without the detachable keyboard. With the keyboard it operates just like other Atari 8-bit computer models. The cartridge slot is on the top, like other consoles.

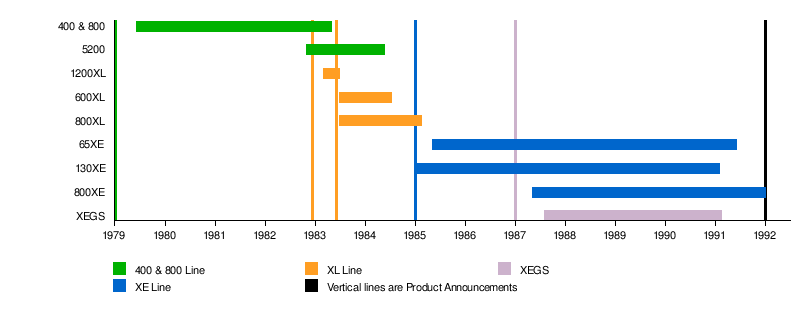

Production timeline

edit

The production timeline is from 1979 to 1987.[68][74]

Prototypes and vaporware

edit- 1400XL: similar to the 1200XL but with a PBI, FREDDIE chip, built-in modem and a Votrax SC-01 speech synthesis chip. Cancelled.

- 1450XLD: a 1400XL with built-in 5+1⁄4″ disk drive and expansion bay for a second 5+1⁄4″ disk drive. Code named Dynasty. Made it to pre-production, but was abandoned by Tramiel.

- 1600XL: codenamed Shakti, this was dual-processor system with 6502 and 80186 processors and two built-in 5+1⁄4″ floppy disk drives.[75]

- 1850XL: codenamed Mickey, this was to use the "Lorraine" (aka "Amiga") custom graphics chips

- 65XEM: 65XE with AMY sound synthesis chip. Cancelled.

- 65XEP: "portable" 65XE with 3+1⁄2" disk drive, 5" green CRT and battery pack.

Peripherals

editDuring the lifetime of the 8-bit series, Atari released a large number of peripherals including cassette tape drives, 5.25-inch floppy drives, printers, modems, a touch tablet, and an 80-column display module.

Atari's peripherals use the proprietary Atari SIO port, which allows them to be daisy chained together. A primary goal of the Atari computer design was user-friendliness which was assisted by the SIO bus. Since only one kind of connector plug is used for all devices the Atari computer was easy for novice users to expand. Atari SIO devices use an early form of plug-n-play. Peripherals on the bus have their own IDs, and can deliver downloadable drivers to the Atari computer during the boot process. The additional electronics in these peripherals made them cost more than the equivalent "dumb" devices used by other systems of the era.

Software

editAtari did not initially disclose technical information for its computers, except to software developers who agreed to keep it secret, possibly to increase its own software sales.[34] Cartridge software was so rare at first that InfoWorld joked in 1980 that Atari owners might have considered turning the slot "into a fancy ashtray". The magazine advised them to "clear out those cobwebs" for Atari's Star Raiders,[76] which became the platform's killer app, akin to VisiCalc for the Apple II in its ability to persuade customers to buy the computer.[77][78]

Chris Crawford and others at Atari published detailed technical information in De Re Atari.[79] In 1982, Atari published both the Atari Home Computer System Hardware Manual[80] and an annotated source listing of the operating system. These resources resulted in many books and articles about programming the computer's custom hardware.

Because of graphics superior to those of the Apple II[81] and Atari's home-oriented marketing, games dominated its software library. A 1984 compendium of reviews used 198 pages for games compared to 167 for all others.[82]

Built-in operating system

editThe Atari 8-bit computers have an operating system built into the ROM. The Atari 400 and 800 have two versions:

- OS Rev. A – 10 KB ROM (3 chips) early machines

- OS Rev. B – 10 KB ROM (3 chips) most common

The XL/XE all have OS revisions, which created compatibility issues with certain software. Atari responded with the Translator Disk, a floppy disk which loads the older 400 and 800 Rev. 'B' or Rev. 'A' OS into the XL/XE computers.

- OS Rev. 10 – 16 KB ROM (2 chips) for 1200XL Rev A

- OS Rev. 11 – 16 KB ROM (2 chips) for 1200XL Rev B (bug fixes)

- OS Rev. 1 – 16 KB ROM for 600XL

- OS Rev. 2 – 16 KB ROM for 800XL

- OS Rev. 3 – 16 KB ROM for 800XE/130XE

- OS Rev. 4 – 32 KB ROM (16 KB OS + 8 KB BASIC + 8 KB Missile Command) for XEGS

The XL/XE models that followed the 1200XL also have the Atari BASIC ROM built-in, which can be disabled at startup by holding down the silver OPTION key. Originally this was revision B, which has some serious bugs. Later models have revision C.

Disk Operating System

editThe standard Atari OS only contains low-level routines for accessing floppy disk drives. An extra layer, a disk operating system, is required to assist in organizing file system-level disk access. Atari DOS has to be booted from floppy disk at every power-on or reset. Atari DOS is entirely menu-driven.

- DOS 1.0

- DOS 2.0S – Improved over DOS 1.0; became the standard for the 810 disk drive.

- DOS 3.0 – Came with 1050 drive. Uses a different disk format which is incompatible with DOS 2.0, making it unpopular.

- DOS 2.5 – Replaced DOS 3.0 with later 1050s. Functionally identical to DOS 2.0S, but able to read and write enhanced density disks.

- DOS XE – Designed for the Atari XF551 double-density drive.

Third-party replacement DOSes were also available.

Legacy

editAt the beginning of 1992, Atari Corporation officially dropped all remaining support for all the 8-bit computers.[10] In 2006, Curt Vendel, who designed the Atari Flashback,[83] claimed that Atari released the 8-bit chipset into the public domain.[84] There is agreement in the community that Atari authorized the distribution of the Atari 800's ROM with the Xformer 2.5 emulator, which makes the ROM legally available today as freeware.[85][86]

On March 29, 2024, Atari SA and Retro Games Ltd, via the distributor Plaion, released the Atari 400 Mini, at a cost of £99.99 (€119.99 / $119.99). It is a half-sized scale-model microconsole emulation of the Atari 400. preloaded with 25 games. It comes with an updated Atari CX40 joystick with additional buttons.[87][88]

References

edit- ^ a b Benj Edwards (December 21, 2019). "How Atari took on Apple in the 1980s home PC wars". Fast Company.

- ^ a b Jamie Lendino (June 27, 2022). "Atari Turns 50: A Look Back on the Original Name in Video Games". PC Magazine.

- ^ a b "Atari introduces the 400/800 computers". Creative Computing. 5 (8): 26. August 1979.

- ^ Atari 800 Home Computer System Salesperson's Guide. Atari, Inc. 1982.

- ^ Atari's PC Evolution The History of Atari Computers, Benj Edwards, PC World April 21, 2011, retrieved August 20 2016.

- ^ a b c d "Computer Systems". Atari. Archived from the original on May 5, 2021. Retrieved September 23, 2019.

- ^ "Atari 800 in store demo". games.greggman.com.

- ^ a b c Reimer, Jeremy (December 7, 2012). "Total Share: Personal Computer Market Share 1975-2010". Jeremy Reimer. Archived from the original on July 5, 2019. Retrieved November 27, 2021.

- ^ Jeremy Reiner (December 15, 2005). "Total share: 30 years of personal computer market share figures". ArsTechnica.

- ^ a b Poehland, Ben (December 1992). "Editor's Desk". Atari Classics. Vol. 1, no. 1. Ann Arbor, MI: Unicorn Publications. p. 4. Retrieved April 6, 2021.

- ^ Fulton, Steve (November 6, 2007). "The History of Atari: 1971-1977". Gamasutra. para. 1974: The Crunch Hits. Retrieved July 23, 2023.

- ^ a b c Joe Decuir, "3 Generations of Game Machine Architecture" Archived March 13, 2012, at the Wayback Machine, CGEXPO99

- ^ Atari Home Computer Field Service Manual - 400/800 (PDF). Atari, Inc. pp. 1–10.

- ^ "Most Important Companies". Byte Magazine. September 1995. Archived from the original on June 18, 2008. Retrieved June 10, 2008.

- ^ Fisher, Adam (2018). Valley of genius: the uncensored history of Silicon Valley, as told by the hackers, founders, and freaks who made it boom. New York: Twelve. ISBN 978-1-4555-5902-2. OCLC 1042088095.

- ^ a b Crawford, Chris (1982). De Re Atari. Atari.

- ^ Archived at Ghostarchive and the Wayback Machine: Peddle, Chuck (June 12, 2014). "Oral History of Chuck Peddle" (Interview). Interviewed by Doug Fairbairn and Stephen Diamond. 1:56:30.

- ^ Fulton, Steve (August 21, 2008). "Atari: The Golden Years A History, 1978 1981". Gamasutra. p. 4.

- ^ Goldberg & Vendel 2012, p. 455.

- ^ a b Tomczyk, Michael S. (1981). "Atari's Marketing Vice President Profiles the Personal Computer Market". Compute!'s First Book of Atari. Compute! Books. p. 2. ISBN 0-942386-00-0.

- ^ Goldberg & Vendel 2012, p. 456.

- ^ Goldberg & Vendel 2012, p. 460.

- ^ Wilkinson, Bill (1982). Inside Atari Basic. COMPUTE! Books.

- ^ a b Goldberg & Vendel 2012, p. 466.

- ^ "3-The Apple II". Apple II History. November 30, 2008.

- ^ Schuyten, Peter J. (December 6, 1978). "Technology; The Computer Entering Home". Business & Finance. The New York Times. p. D4. ISSN 0362-4331.

- ^ Craig, John (April 1979). "Winter Consumer Electronics Show". Creative Computing. Vol. 5, no. 4. p. 16. Retrieved May 25, 2014.

- ^ Vendel, Curt. "The Atari 800". Atari Museum. Archived from the original on December 8, 2012. Retrieved October 20, 2016.

- ^ a b Edwards, Benj (November 4, 2009). "Inside the Atari 800". PC World. Retrieved July 19, 2014.

- ^ a b Halfhill, Tom R. (March 1983). "Atari's New Top-Line Home Computer". Compute!. p. 66. Retrieved June 30, 2014.

- ^ Craig, John (April 1979). "Winter Consumer Electronics Show". Creative Computing. p. 16.

- ^ Ahl, David (August 1979). "Atari Speaks Out". Creative Computing. pp. 58–59.

- ^ Lindsay, Len (April 1980). "Atari in Perspective". Creative Computing. pp. 22–30.

- ^ a b Nelson, Ted (June 1980). "The Atari Machine". Creative Computing. pp. 34–35, 37.

- ^ Derfler, Frank J. Jr. (September 1980). "Moonshine, Dixie and the Atari 800". Kilobaud. pp. 100–103. Retrieved June 23, 2014.

- ^ a b Hogan, Thom (May 11, 1981). "The Atari 800 Personal Computer". InfoWorld. pp. 34–35.

- ^ a b Hogan, Thom (August 31, 1981). "From Zero to a Billion in Five Years". InfoWorld. pp. 6–7.

- ^ Thom, Hogan (September 14, 1981). "State of Microcomputing: Some Horses Running Neck and Neck". InfoWorld. pp. 10–12. Retrieved February 9, 2023.

- ^ a b Current 2023, 1.12) What are SALLY, ANTIC, CTIA/GTIA/FGTIA, POKEY, and FREDDIE?.

- ^ "Atari introduces the 1200XL computer" (Press release). New York: Atari, Inc. PR Newswire. December 13, 1982.

- ^ Anderson, John (1983). "New Member of the Family - Atari 1200". In Small, David; Small, Sandy; Blank, George (eds.). The Creative Atari. Morris Plains, NJ: Creative Computing Press. p. 116. ISBN 0-916688-34-8. Retrieved May 7, 2014.

- ^ a b Ahl, David H.; Staples, Betsy (April 1983). "1983 Winter Consumer Electronics Show; Creative Computing presents the Short Circuit Awards". Creative Computing. Vol. 9, no. 3. Ahl Computing. p. 50. ISSN 0097-8140. Archived from the original on July 2, 2013.

- ^ Goldberg & Vendel 2012, p. 698:

Released in early 1983, it will only remain in production until June 1983.

- ^ a b Lock, Robert (June 1983). "Editor's Notes". Compute!. p. 6. Retrieved October 30, 2013.

- ^ Lock, Robert (February 1983). "Editor's Notes". Compute!. p. 8. Retrieved October 30, 2013.

- ^ Anderson, John (May 1983). "Outpost: Atari". Creative Computing: 272.

- ^ Wilkinson, Bill (May 1983). "INSIGHT: Atari". Compute!. p. 198. Retrieved October 30, 2013.

- ^ a b Bisson, Gigi (May 1986). "Antic Then & Now". Antic. pp. 16–23. Retrieved January 28, 2015.

- ^ Reid, T. R. (February 6, 1984). "Coleco's 'Adam' Gets Gentleman's 'C' for Performance". The Washington Post.

- ^ a b Moriarty, Brian; Nowell, Robin E.; Franklin, Austin (January 1984). "Inside the Atari 600XL". ANALOG Computing. p. 32.

- ^ Wessel, David (November 10, 1983). "Atari, Coleco to Raise Prices of Home Computers on January 1". The Boston Globe.

- ^ Mace, Scott (February 27, 1984). "Can Atari Bounce Back?". InfoWorld. p. 100.

- ^ ""Atari 1600XL"". Archived from the original on September 13, 2011. Retrieved April 14, 2008.

- ^ "Afterthoughts: The Atari 1600XL Rumor". Archived from the original on April 15, 2009. Retrieved September 19, 2008.

- ^ Kleinfield, N. R. (December 22, 1984). "Trading Up in Computer Gifts". The New York Times.

- ^ Maremaa, Tom (June 3, 1985). "Atari Ships New 520 ST". InfoWorld. p. 23.

- ^ Pollack, Andrew (December 19, 1982). "THE GAME TURNS SERIOUS AT ATARI (Published 1982)". The New York Times. p. Section 3, Page 1. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved February 18, 2021.

- ^ Anderson, John J. (March 1984). "Atari". Creative Computing. p. 51.

- ^ Capparell, James (May 1985). "and we won't take it anymore!". Antic. pp. 8, 10.

- ^ Leyenberger, Arthur (February 1986). "The End User". ANALOG Computing. pp. 109–110.

- ^ a b Williams, Gregg (January–February 1986). "Atari Playfield" (PDF). Computer Gaming World. No. 25. p. 32.

- ^ "Survey of Game Manufacturers" (PDF). Computer Gaming World. No. 27. April 1986. p. 32. Retrieved April 17, 2016.

- ^ a b Williams, Gregg (September–October 1986). "Atari Playfield" (PDF). Computer Gaming World. No. 31. p. 35.

- ^ Brooks, M. Evan (May 1987). "Computer Wargaming 1988-1992". Computer Gaming World. No. 37. p. 13.[permanent dead link]

- ^ Brooks, M. Evan (November 1987). "Titans of the Computer Gaming World / MicroProse" (PDF). Computer Gaming World. No. 41. p. 17.

- ^ Jack Tramiel - Atari - Rare UK TV Appearance. Archived from the original on July 24, 2019. Retrieved August 6, 2022 – via YouTube.

- ^ Lendino, Jamie (2017). Murray, Matthew (ed.). Breakout: How Atari 8-Bit Computers Defined a Generation. Ziff Davis. p. 106. ISBN 978-0692851272.

- ^ a b c Current 2023, 1.10) What is the Atari 800XE?.

- ^ Small, David; Small, Sandy; Blank, George (1983). The Creative Atari. Creative Computing Press. ISBN 978-0-916688-34-9. Retrieved December 18, 2023.

- ^ De Re Atari Anno Domini MCMLXXXI: A Guide to Effective Programming of the Atari 400/800 Home Computer. Atari, Inc. 1981. Retrieved December 18, 2023.

- ^ a b "I. Theory of Operation". Atari Home Computer Field Service Manual - 400/800 (PDF). Atari, Inc. pp. 1–10. Retrieved September 10, 2010.

- ^ Mapping The Atari, Ian Chadwick and Atari 130XE owner's manual

- ^ Multipede—Trouble shooting guide, Braze Technologies

- ^ Polsson, Ken (April 3, 2014). "Chronology of Personal Computers". p. 1978. Archived from the original on September 12, 2015. Retrieved February 5, 2015.

- ^ "1600XL information". Archived from the original on September 13, 2011. Retrieved April 14, 2008.

- ^ Cole, David C. (July 7, 1980). "Star Raiders from Atari". InfoWorld. p. 13.

- ^ Williams, Gregg (May 1981). "Star Raiders". BYTE. p. 106.

- ^ Goldberg & Vendel 2012, p. 526.

- ^ "The quarterly APX contest / APX: Programs by our users...for our users / Publications / Hardware". APX Product Catalog. Fall 1983. pp. 34, 72. Retrieved July 29, 2014.

- ^ Atari Home Computer System Hardware Manual (PDF). Atari, Inc. 1982.

- ^ Pournelle, Jerry (July 1982). "Computers for Humanity". BYTE. p. 392.

- ^ Stanton, Jeffrey; Wells, Robert P.; Rochowansky, Sandra; Mellid, Michael, eds. (1984). The Addison-Wesley Book of Atari Software. Addison-Wesley. pp. TOC, 12, 210. ISBN 0-201-16454-X.

- ^ "Atari Flashback". IGN. December 15, 2015. Retrieved September 23, 2019.

- ^ FB3... by Curt Vendel on atariage.com "Atari released the Atari 8bit chipset into PD for me several years ago, so any FB3 project at this point could very well turn into a PD or individual released project/product"

- ^ "Atari800Win PLus - The Atari 8-bit Emulator: News". atariarea.krap.pl.

- ^ HOW TO GET ROMS FOR "RAINBOW" (ATARI XL EMULATOR)! The answer on groups.google.com (1995)

- ^ "AN ICON RETURNS: RETRO GAMES LTD. AND PLAION ANNOUNCE MINI RECREATION OF THE ATARI 400™ Press Server". presse.plaion.com. January 11, 2024.

- ^ Webster, Andrew (March 30, 2024). "The Atari 400 Mini is a cute little slice of video game history". The Verge. Retrieved March 30, 2024.

Bibliography

edit- "The Atari 800 Personal Computer System". Atari Museum. Archived from the original on December 8, 2012. Retrieved November 13, 2008.

- Goldberg, Marty; Vendel, Curt (2012). Atari Inc: Business is Fun. Syzygy Press. ISBN 9780985597405.

- Levy, Steven (1984). Hackers: Heroes of the Computer Revolution. Doubleday. ISBN 0-385-19195-2.

- Alcorn, Al (April 12, 2015). "ANTIC Interview 32 - Al Alcorn, Atari Employee #3". Antic (Interview). Interviewed by Randy Kindig.

- Current, Michael D. (May 29, 2023) [1992]. "Atari 8-Bit Computers: Frequently Asked Questions". Retrieved October 10, 2023.

External links

edit- Atari 400/800 Peripherals Archived December 11, 2014, at the Wayback Machine

- "A History of Gaming Platforms: Atari 8-bit Computers" at Gamasutra

- Atari XL Series Systems & Prototypes Archived July 2, 2019, at the Wayback Machine

- Technical chipset information