The 21 Special Air Service Regiment (Artists) (Reserve), historically known as The Artists Rifles[nb 1] is a regiment of the Army Reserve. Its name is abbreviated to 21 SAS(R).

| The Artists Rifles | |

|---|---|

Cap badge of The Artists Rifles | |

| Active | 1859–1945 1947–present |

| Country | |

| Branch | Army Reserve |

| Type | Special forces |

| Role | Special operations |

| Part of | United Kingdom Special Forces |

| Garrison/HQ | Regent's Park Barracks, London, United Kingdom |

| Engagements | |

| Decorations | 8 VCs, 56 DSOs, 893 MCs, 26 DFCs, 15 AFCs, 6 DCMs, 15 MMs, 14 MSMs, 564 MIDs (First World War) |

| Commanders | |

| Notable commanders | Henry Wyndham Phillips and Frederic Leighton |

Raised in London in 1859 as a volunteer light infantry unit, the regiment saw active service during the Second Boer War and the First World War, earning a number of battle honours. During the Second World War, it was used as an officer training unit. The regiment was disbanded in 1945, but in 1947 it was re-established to resurrect the Special Air Service Regiment.[2] Together with 23 Special Air Service Regiment (Reserve) (23 SAS(R)), it forms the Special Air Service (Reserve) (SAS(R)) part of the United Kingdom Special Forces (UKSF) directorate.[3]

History

editFormation and 19th century

editThe regiment was established in 1859, part of the widespread volunteer movement which developed in the face of potential French invasion after Felice Orsini's attack on Napoleon III was linked to Britain.[4] The group was organised in London by Edward Sterling, an art student, and comprised various professional painters, musicians, actors, architects and others involved in creative endeavours; a profile it strove to maintain for some years. It was established on 28 February 1860 as the 38th Middlesex (Artists') Rifle Volunteer Corps, with headquarters at Burlington House.[1] Its first commanders were the painters Henry Wyndham Phillips and Frederic Leighton. The unit's badge, designed by J. W. Wyon, shows the heads of the Roman gods Mars and Minerva in profile.[5] Until 1914 the regimental full dress uniform was light grey with white facings, silver buttons and braid. This distinctive uniform dated from the regiment's foundation as a volunteer unit. After the First World War, standard khaki was the normal dress.[6]

In September 1880, the corps became the 20th Middlesex (Artists') Rifle Volunteer Corps, with headquarters at Duke's Road, off Euston Road, London (now The Place, home of the Contemporary Dance Trust). The drill hall was designed by Robert William Edis, the commanding officer.[7] It was officially opened by the Prince of Wales.[7]

It formed the 7th Volunteer Battalion of the Rifle Brigade from 1881 until 1891 and the 6th Volunteer Battalion from 1892 to 1908. During this period, The Artists' Rifles fought in the Second Boer War as part of the City Imperial Volunteers.[8]

After the 1860s the voluntary recruitment basis of the regiment gradually broadened to include professions other than artistic ones. By 1893 lawyers and architects made up 24% of the unit, doctors followed with 10% and civil engineers 6%. Sculptors and painters totaled about 5%.[9]

20th century

editFollowing the formation of the Territorial Force, the Artists' Rifles was one of 26 volunteer battalions in the London and Middlesex areas that combined to form the new London Regiment.[nb 2] It became the 28th (County of London) Battalion of The London Regiment on 1 April 1908.[11]

The Artists' Rifles was a popular unit for volunteers. It had been increased to twelve companies in 1900 and was formed into three sub-battalions in 1914, and recruitment was eventually restricted by recommendation from existing members of the battalion. It particularly attracted recruits from public schools and universities; on this basis, following the outbreak of the First World War, a number of enlisted members of The Artists' Rifles were selected to be officers in other units of the 7th Division.[1] This exercise was so successful that, early in 1915, selected Artists' officers and NCOs were transferred to run a separate Officers Training Corps, in which poet Wilfred Owen trained before posting to the Manchester Regiment,[12] the remainder being retained as a fighting unit. Over fifteen thousand men passed through the battalion during the war, more than ten thousand of them becoming officers.[13] The battalion eventually saw battle in France in 1917 and 1918. Casualties suffered by members of this battalion and amongst officers who had trained with The Artists' Rifles before being posted to other regiments were 2,003 killed, 3,250 wounded, 533 missing and 286 prisoners of war.[1] Ex-Members of the Regiment won eight Victoria Crosses (though none did so while serving with the Regiment), fifty-six DSOs and over a thousand other awards for gallantry.[13]

In the early 1920s, the unit was reconstituted as an infantry regiment within the Territorial Army, as the 28th County of London Regiment. In 1937, this regiment became part of The Prince Consort's Own Rifle Brigade.[14]

The regiment was not deployed during the Second World War, functioning again as an Officers Training Corps throughout the war.[1]

History as 21 SAS(R)

editThe unit was disbanded in 1945, but reformed in The Rifle Brigade in January 1947 and transferred to The Army Air Corps in July as the 21st Special Air Service Regiment (Artists Rifles).[15] The number 21 SAS was chosen to perpetuate two disbanded wartime regiments, 2 SAS and 1 SAS. The unit was active during the Malayan Emergency and in many subsequent conflicts. In 1952, members of The Artists Rifles who had been involved in special operations in Malaya formed 22 SAS Regiment, the regular special forces regiment – at the time, the only time a Territorial Army unit had been used to form a unit in the Regular Army.[16]

In 1985, David Stirling, founder of the SAS, commented: "There is one often neglected factor which I would like to emphasize - the importance of the two SAS Territorial regiments. At the start of the Second World War, and during its early stages, it was the ideas and initiatives of these amateur soldiers which led to the creation of at least two units within the Special Forces and gave a particular elan to others. When, however, a specialist unit becomes part of the military establishment, it runs the risk of being stereotyped and conventionalized. Luckily the modern SAS looks safe from this danger; it is constantly experimenting with innovative techniques, many of which stem from its Territorial regiments, drawn as they are from every walk of civilian life."[17]

For much of the Cold War, 21 SAS's role was to provide stay-behind parties in the event of a Warsaw Pact invasion of western Europe, forming (alongside 23 SAS) I Corps' Corps Patrol Unit.[18] In the case of an invasion, this Special Air Service Group would have let themselves be bypassed and stay-behind in order to collect intelligence behind Warsaw Pact lines and conduct target acquisition, and thus try to slow the enemy's advance.[19] Peter de la Billière, who later commanded 22 SAS and then became Director Special Forces, served as their adjutant for part of this period. He later wrote: "People began to see that the Territorial SAS were first class and enhanced the reputation of the whole Regiment in a special way of their own."[20]

By early 2003, a composite squadron of 21 and 23 SAS, was operating in Helmand for roles against Al Qaeda forces, 'with the emphasis on long range reconnaissance'.[21][22][23][24] It was reported that the workload undertaken and the results achieved by the territorial SAS in Afghanistan 'greatly impressed their American commanders, who are keen to keep using them on operations for as long as possible'.[21] In 2007-8 a squadron-sized sub-unit was deployed first from 23 and then from 21 SAS to Helmand for roles including training the Afghan Police and working with the intelligence services.[25][26] In 2008, members of 21 SAS were sent to Marjah to assist the Afghan police, arriving just in time to see the police flee due to Taliban infiltration of the area. In the same year, a small team from 21 SAS were sent to mentor the Afghan Police in Nad-e Ali, an exposed and logistically challenging location.[26] Three members of 21 SAS were subsequently awarded Military Crosses, as a result of the fighting in Nad-e Ali.[27][28] A further member of 21 won a Conspicuous Gallantry Cross at a later date in Afghanistan.[27]

On 1 September 2014, 21 and 23 SAS were moved from United Kingdom Special Forces and placed under the command of 1st Intelligence, Surveillance and Reconnaissance Brigade.[29][30] The units then left that brigade before the end of 2019.[31] Today, the two reserve regiments, 21 SAS and 23 SAS are back under the operational command of the Director Special Forces, as an integrated part of United Kingdom Special Forces.[32]

Organisation

edit21 Special Air Service Regiment (Artists) (Reserve) currently consists of:[33]

- 'Cap' (Capability) Squadron (Regent's Park)

- 'A' Squadron (Regent's Park)

- 'C' Squadron (Basingstoke/Cambridge/Hitchin)

- 'E' Squadron (Newport/Exeter)

Commanding officers

edit- 1869–1883 Lieutenant-Colonel Sir Frederic Leighton[34]

- 1883–1902 Colonel Robert William Edis, CB[34][35]

- 1902–? Colonel W. C. Horsley [35]

- 1962-65 Sir William Macpherson[36]

Honorary Colonels

editBattle honours

edit- Second Boer War

- The Great War (3 battalions): Ypres 1917, Passchendaele, Somme 1918, St. Quentin, Bapaume 1918, Arras 1918, Ancre 1918, Albert 1918, Drocourt-Quéant, Hindenburg Line, Canal du Nord, Cambrai 1918, Pursuit to Mons, France and Flanders 1914–18.[1]

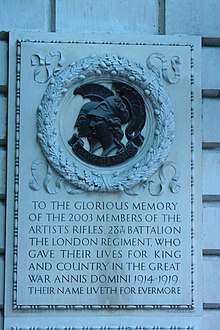

War memorial

editThe unit's war memorial in the entrance portico of the Royal Academy at Burlington House commemorates the 2,003 men who gave their lives in the Great War, with a second plaque dedicated to those who died in the Second World War.[38]

Victoria Cross

editAlthough no-one has won the VC while serving with the Artists Rifles, the following have been awarded the Victoria Cross before or after serving in the regiment:

- 2nd Lt Rupert Price Hallowes, 4th Battalion, The Middlesex Regiment (Duke of Cambridge's Own)

- 2nd Lt Arthur James Terence Fleming-Sandes, 2nd Battalion, The East Surrey Regiment

- Capt The Rev Edward Noel Mellish, Royal Army Chaplains' Department

- Lt Geoffrey St George Shillington Cather, 9th Battalion, The Royal Irish Fusiliers

- Lt Eugene Paul Bennett, 2nd Battalion, The Worcestershire Regiment

- 2nd Lt George Edward Cates, 2nd Battalion, The Rifle Brigade (Prince Consort's Own)

- Lt Donald John Dean, 8th Battalion, The Queen's Own Royal West Kent Regiment

- Lt Col Bernard William Vann, 1/8th Bn, Sherwood Foresters

- Lt Col Augustus Charles Newman, No. 2 Commando

See also

editNotes

edit- ^ Originally the regiment was designated as The Artists' Rifles until the apostrophe was officially dropped from the full title in 1937, as it was so often misused.[1]

- ^ The Honourable Artillery Company and The Inns of Court Regiment were intended to become the 26th and 27th Battalions of the London Regiment. They were not satisfied with their high numbers so ignored them.[10]

References

edit- ^ a b c d e f "Regiment page". Artists Rifles Association. 2016. Archived from the original on 5 April 2023.

- ^ Gregory, p. 297

- ^ "21 & 23 Special Air Service (SAS)". British Army. Retrieved 26 August 2020.

- ^ Gregory 2006, p. xvi.

- ^ Mars-Minerva (JPEG), Artists Rifles Association

- ^ "Artists Rifles Association". Retrieved 30 December 2014.

- ^ a b Historic England. "The Place and attached railings, Camden (1342089)". National Heritage List for England.

- ^ Gregory 2006, p. 80.

- ^ "Artists Rifles Association". Retrieved 20 April 2012.

- ^ Westlake 1986, p. 233.

- ^ Gregory 2006, p. 96.

- ^ "No. 29617". The London Gazette (Supplement). 6 June 1916. p. 5726.

- ^ a b Higham 2006, p. xviii.

- ^ Gregory 2006, p. 253.

- ^ Gregory 2006, p. 297.

- ^ Shortt 1994, pp. 16–17.

- ^ Seymour, Preface

- ^ Asher, Michael (2008). The Regiment: The True Story of the SAS. London: Penguin UK. ISBN 978-0141026527.

- ^ Sinai, Tamir (8 December 2020). "Eyes on target: 'Stay-behind' forces during the Cold War". War in History. 28 (3): 681–700. doi:10.1177/0968344520914345.

- ^ de la Billiere, p. 161

- ^ a b Rayment, Sean (28 December 2003). "Overstretched SAS calls up part-time troops for Afghanistan". The Daily Telegraph. London. Archived from the original on 23 March 2010

- ^ Smith, Michael (20 November 2005). "Part-time SAS sent to tackle Taliban". Sunday Times.

- ^ Jennings, p 187 & 246

- ^ Neville, Leigh, Special Forces in the War on Terror (General Military), Osprey Publishing, 2015 ISBN 978-1-4728-0790-8,p.75

- ^ Smith, Michael; Starkey, Jerome (22 June 2008). "Bryant was on secret mission in Afghanistan". The Sunday Times.

- ^ a b Farrell, p. 246-247

- ^ a b "Question By Philip Hollobone MP and answer by James Heappey, MO Min AF". Hansard. Retrieved 21 April 2021.

- ^ "Revealed: nearly half of Special Forces could go in deepest cuts in 50 years". www.telegraph.co.uk. 3 March 2013.

- ^ Janes International Defence Review, May 2014, p. 4

- ^ Army Briefing Note 120/14, NEWLY FORMED FORCE TROOPS COMMAND SPECIALIST BRIGADES, Quote . It commands all of the Army's Intelligence, Surveillance and EW assets, and is made up of units specifically from the former 1 MI Bde and 1 Arty Bde, as well as 14 Sig Regt, 21 and 23 SAS(R).

- ^ "Force Troops Command Handbook". Ministry of Defence. Retrieved 11 January 2021.

- ^ "21 & 23 SAS (Reserve)". www.army.mod.uk. Retrieved 29 December 2020.

- ^ "The Artists Rifles - From Pre-Raphaelites to Passchendaele" (PDF). ARQ Army Reserve Quarterly. Andover: Army Media & Communication. Autumn 2014. p. 21. Archived from the original (PDF) on 14 February 2015.

- ^ a b c "No. 25251". The London Gazette. 17 July 1883. p. 3588.

- ^ a b c "No. 27508". The London Gazette. 23 December 1902. p. 8848.

- ^ Bootland, Morag (14 December 2018). "The Macpherson clan chief believes in family". Scottish Field. Retrieved 19 June 2020.

- ^ "No. 28287". The London Gazette. 10 September 1909. p. 6815.

- ^ "Artists Rifles War Memorial". London remembers. Retrieved 28 May 2017.

Bibliography

edit- Asher, Michael (2007). The Regiment: The Real Story of the SAS. Viking. ISBN 978-0-67091-633-7. (republished in 2018 as The Regiment: The Definitive Story of the SAS)

- Ballinger, Adam (1992). The Quiet Soldier. Chapmans. ISBN 978-1-85592-606-6.

- de la Billiere, Peter (1995). Looking for Trouble:SAS to Gulf Command. HarperCollins.

- Farrell, Theo (2017). Unwinnable: Britain's War in Afghanistan, 2001–2014. Bodley Head. ISBN 978-1847923462.

- Gregory, Barry (2006). A History of The Artists Rifles 1859–1947. Barnsley: Pen & Sword Books. ISBN 978-1-84415-503-3.

- Hacking, Juliet (2000). Princes of Victorian Bohemia. National Portrait Gallery.

- Higham, S Stagoll (2006) [1922, Howlett & Son]. Artists Rifles: Regimental Roll of Honour and War Record 1914–1919 (3rd ed.). London: Naval & Military Press. ISBN 978-1-84734-129-7.

- Jennings, Christian (2005). Midnight in some burning town: British Special Forces: Operations from Belgrade to Baghdad. Cassell. ISBN 0-3043-6708-7.

- Seymour, William (1985). British Special Forces: The Story of Britain's Undercover Soldiers. Pen and Sword.

- Shortt, James G. (1994). The Special Air Service. Men-at-Arms-Series, 116. London: Osprey. ISBN 9780850453966.

- Westlake, Ray (1986). The Territorial Battalions: A Pictorial History, 1859–1985. Tunbridge Wells: Spellmount.

- Winter, JM (1977). "Britain's 'Lost Generation' of the First World War". Population Studies. 31 (3): 459. doi:10.1080/00324728.1977.10412760. PMID 11630506.

External links

edit