You can help expand this article with text translated from the corresponding article in German. (October 2022) Click [show] for important translation instructions.

|

Anton Wilhelm Amo or Anthony William Amo (c. 1703 – c. 1759) was a Nzema philosopher from Axim, Dutch Gold Coast (now Ghana). Amo was a professor at the universities of Halle and Jena in Germany after studying there. He was brought to Germany by the Dutch West India Company in 1707 and was presented as a gift to Dukes Augustus William and Ludwig Rudolf of Brunswick-Wolfenbüttel,[2] being treated as a member of the family by their father Anthony Ulrich, Duke of Brunswick-Wolfenbüttel. In 2020, Oxford University Press published a translation (into English) of his Latin works from the early 1730s.[3]

Anton Wilhelm Amo | |

|---|---|

Drawing of Anton Wilhelm Amo | |

| Born | c. 1703 |

| Died | c. 1759 (aged 55–56) |

| Other names | Antonius Guilielmus Amo Afer Anthony William Amo |

| Academic background | |

| Education | University of Helmstedt University of Halle University of Wittenberg |

| Thesis | Disputatio Philosophica continens Ideam Distinctam Eorum quae competunt vel menti vel corpori nostro vivo et organico (1734) |

| Academic advisors | Samuel Christian Hollmann Martin Gotthelf Löscher |

| Influences | |

| Academic work | |

| Era | Contemporary philosophy |

| School or tradition | Western philosophy, rationalism |

| Institutions | University of Halle University of Jena |

| Doctoral students | Johannes Theodosius Meiner |

| Main interests | Philosophy of mind |

| Notable ideas | Critique of Descartes' philosophy of mind[1] |

Early life and education

editAmo was a Nzema (an Akan people). He was born in Axim in the Western region of present-day Ghana, but at the age of about four he was moved to Amsterdam by the Dutch West India Company. Some accounts say that he was enslaved, others that he was sent to Amsterdam by a preacher working in Ghana. Ultimately, it is unknown.

On 29 July 1708, Amo was baptised (and in 1721 confirmed) in the palace's chapel of Salzdahlum near Wolfenbüttel. In 1721 and 1725 he is mentioned as a servant to the Duke's family.

He went on to the University of Halle, whose Law School he entered in 1727. He finished his preliminary studies within two years, titling his thesis Dissertatio Inauguralis de Jure Maurorum in Europa (1729).[4] This manuscript on The Rights of Moors in Europe is lost, but a summary was published in his university's Annals (1730). For his further studies Amo moved to the University of Wittenberg, studying logic, metaphysics, physiology, astronomy, history, law, theology, politics, and medicine, and mastered six languages (English, French, Dutch, Latin, Greek, and German). His medical education in particular was to play a central role in much of his later philosophical thought.

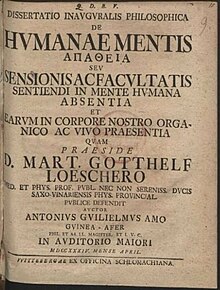

He gained his doctorate in philosophy at Wittenberg in 1734; his thesis (published as On the Absence of Sensation in the Human Mind and its Presence in our Organic and Living Body) argued in favour of a broadly dualist account of the person. Specifically, he argues that it is correct to talk of a mind and a body, but that it is the body rather than the mind that perceives and feels.[5] One example of an argument that Amo uses to show that it is the body, and not the mind, which senses goes as follows:

Whatever feels, lives; whatever lives, depends on nourishment; whatever lives and depends on nourishment grows; whatever is of this nature is in the end resolved into its basic principles; whatever comes to be resolved into its basic principles is a complex; every complex has its constituent parts; whatever this is true of is a divisible body. If therefore the human mind feels, it follows that it is a divisible body.

- (On the Ἀπάθεια (Apatheia) of the Human Mind 2.1)

Because (on Amo's account) the human mind is by definition immaterial and not a divisible body (On the Ἀπάθεια (Apatheia) of the Human Mind 1.3), it therefore cannot be the case that the mind itself senses.

Philosophical career and later life

editAmo returned to the University of Halle to lecture in philosophy under his preferred name of Antonius Guilielmus Amo Afer. In 1736 he was made a professor.[4] From his lectures, he produced his second major work in 1738, Treatise on the Art of Philosophising Soberly and Accurately,[4] in which he developed an empiricist epistemology very close to but distinct from that of philosophers such as John Locke and David Hume. In it he also examined and criticised faults such as intellectual dishonesty, dogmatism, and prejudice.

In 1740, Amo took up a post in philosophy at the University of Jena, but while there he experienced a number of changes for the worse. The Duke of Brunswick-Wolfenbüttel had died in 1735, leaving him without his long-standing patron and protector.[4] That coincided with social changes in Germany, which was becoming intellectually and morally narrower and less liberal. Those who argued against the secularisation of education (and against the rights of Africans in Europe) were regaining their ascendancy over those who campaigned for greater academic and social freedom, such as Christian Wolff.

Amo was subjected to an unpleasant campaign by some of his enemies, including a public lampoon staged at a theatre in Halle. He finally decided to return to the land of his birth. He set sail on a Dutch West India Company ship to Ghana via Guinea, arriving in about 1747; his father and a sister were still living there. His life from then on becomes more obscure. According to at least one report, he was taken to a Dutch fortress, Fort San Sebastian in Shama, in the 1750s, possibly to prevent him sowing dissent amongst the people. The exact date, place, and manner of his death are unknown, though he probably died in about 1759 at the fort in Shama in Ghana.

Honors

editOn 10 October 2020, Google celebrated him with a Google Doodle.[6]

In Stuttgart, an Anton Wilhelm Amo Square in front of the Stuttgart Labour Court was decided in 2022.[7] At the end of January 2023, the square formerly known as "Lerchenplätzle" in front of the Stuttgart Labour Court in Johannesstraße was renamed "Anton-Wilhelm-Amo-Platz".[7] In August 2020, in a context of "decolonization" of place names perceived to have racist origins, officials in the German capital Berlin proposed renaming Mohrenstraße to "Anton-Wilhelm-Amo-Straße" in his honor.[8]

In 2024, two museum exhibitions will be held in Germany that focus exclusively on Anton Wilhelm Amo: "Focus on Amo. Pictures for a Scholar" in the Löwengebäude of the University in Halle/Saale [9] and the exhibition "Anton Wilhelm Amo - Between the Worlds" at the Museum of Municipal Collections in the Zeughaus in Lutherstadt Wittenberg. [10] The curator of this exhibition was the ethnologist Nils Seethaler.[11]

Works

edit- Dissertatio inauguralis de iure maurorum in Europa, 1729 (lost). Translated title: Inaugural dissertation on the laws of the Moors in Europe.

- Dissertatio inauguralis philosophica de humanae mentis apatheia, Wittenberg, 1734. Inaugural dissertation on the impassivity of the human mind.

- Disputatio philosophica continens ideam distinctam eorum quae competunt vel menti vel corpori nostro vivo et organico, Wittenberg, 1734 (Ph.D. thesis).[3] Philosophical discourse presenting ("containing") a distinct idea of what belongs either to the mind or to our living and organic body.

- Tractatus de arte sobrie et accurate philosophandi, 1738. Treatise on the art of philosophising soberly and precisely.

References

edit- ^ Wiredu, Kwasi (2004). "Amo's Critique of Descartes' Philosophy of Mind". In Wiredu, Kwasi: A Companion to African Philosophy. MA, USA, Blackwell Publishing. pp. 200–206.

- ^ Loutzenhiser, Mike (17 September 2008). The role of the indigenous African psyche in the evolution of human consciousness. Bloomington, Ind.: iUniverse. p. xiii. ISBN 978-0595503766.

- ^ a b Menn, Stephen; Smith, Justin E. H. (5 September 2020). Anton Wilhelm Amo's Philosophical Dissertations on Mind and Body. Oxford, New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-750162-7. OCLC 1379043206.

- ^ a b c d Williams, Scott W. (2005). "ANTON-WILHELM AMO, African Professor in 18th century Germany". Mathemathicians of the African Diaspora. Mathematics Department of State University of New York at Buffalo. Archived from the original on 9 May 2005. Retrieved 15 October 2022.

- ^ Lewis, Dwight (8 February 2018). "Anton Wilhelm Amo: The African Philosopher in 18th Europe". Blog of the APA. Retrieved 4 June 2021.

- ^ "Celebrating Anton Wilhelm Amo". Google. 10 October 2020.: "On this day in 1730, Amo received the equivalent of a doctorate in philosophy from Germany’s University of Wittenberg."

- ^ a b Stuttgarter Zeitung, Stuttgart Germany. "Signal against racism: Stuttgart now names a square after Anton Wilhelm Amo after all". Retrieved 2023-01-14.

- ^ Ernst, M. (21 August 2020). "Mohrenstraße wird in Anton-Wilhelm-Amo-Straße umbenannt". RBB (in German). Archived from the original on 11 June 2021. Retrieved 21 August 2020.

- ^ https://pressemitteilungen.pr.uni-halle.de/index.php?modus=pmanzeige&pm_id=5651

- ^ "Sonderausstellung zu Anton Wilhelm Amo startet im Wittenberger Zeughaus".

- ^ "Sonderausstellung zu Anton Wilhelm Amo startet im Wittenberger Zeughaus".

Further reading

edit- Abraham, William E. (1996). "The Life and Times of Anton Wilhelm Amo, the first African (black) Philosopher in Europe". In Asante, Molefi Kete; Abarry, Abu S. (eds.). African Intellectual Heritage. A Book of Sources. Philadelphia: Temple University Press. pp. 424–440. ISBN 1-5663-9403-1.

- Abraham, William E. (2001). "Amo". In Arrington, Robert L. (ed.). A Companion to the Philosophers. Oxford: Blackwell. ISBN 0-631-22967-1.

- Amo, Anton Wilhelm (1968). Antonius Gvilielmus Amo Afer of Axim in Ghana: Translation of his Works. Halle: Martin Luther University, Halle-Wittenberg.

- Brentjes, Burchhard (1969). "Anton Wilhelm Amo in Halle, Wittenberg, und Jena". Mitteilungen des Instituts für Orientforschung (in German). XV: 56–76.

- Firla, Monika (2002). "Anton Wilhelm Amo (Nzema, Rep. Ghana) — Kammermohr, Privatdozent für Philosophie, Wahrsager" [Anton Wilhelm Amo (Nzema, Rep. Ghana) Valet Moor, Private Lecturer of Philosophy, Fortune Teller]. Tribus (in German). 51: 55–90.

- Glötzner, Johannes (2002). "Anton Wilhelm Amo. Ein Philosoph aus Afrika im Deutschland des 18. Jahrhunderts" (in German).

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - Glötzner, Johannes (2003). "Der Mohr. Leben, Lieben und Lehren des ersten afrikanischen Doctors der Weltweisheit Anton Wilhelm Amo" (in German).

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - Herbjørnsrud, Dag (13 December 2017). Dresser, Sam (ed.). "The African Enlightenment. The highest ideals of Locke, Hume and Kant were first proposed more than a century earlier by an Ethiopian in a cave". aeon.co. Aeon digital magazine.

What if the Enlightenment can be found in places and thinkers that we often overlook? Such questions have haunted me since I stumbled upon the work of the 17th-century Ethiopian philosopher Zera Yacob (1599-1692), also spelled Zära Yaqob.

- King, Peter J. (2004). One Hundred Philosophers. New York: Barron's Educational Books. ISBN 0-7641-2791-8.

- Kwame, Safro, ed. (1995). "On the Απαθεια of the Human Mind". Readings in African Philosophy: An Akan Collection. University Press of America. ISBN 0-8191-9911-7.

- Martin, Peter (1993). "Der schwarze Philosoph" [The black Philosopher]. In Martin, Peter (ed.). Schwarze Teufel, Edle Mohren [Black Devils, Noble Moors] (in German). Hamburg: Junius. ISBN 3-930908-64-6.

- Smith, Justin E. H. (10 February 2013). "The Enlightenment's 'Race' Problem, and Ours". The New York Times. Retrieved 2 November 2023.

In 1734, Anton Wilhelm Amo, a West African student and former chamber slave of Duke Anton Ulrich of Braunschweig-Wolfenbüttel, defended a philosophy dissertation at the University of Halle in Saxony, written in Latin and entitled "On the Impassivity of the Human Mind."

External links

edit- Amo, Antonius Guigliemus (1734). "Dissertatio inauguralis de humanae mentis apatheia" [On the Impassivity of the Human Mind]. digital.staatsbibliothek-berlin.de (in Latin). Wittenberg. Retrieved 2 November 2023. At the website of the Berlin State Library.

- Lewis, Dwight (February 8, 2018). "Anton Wilhelm Amo: The African Philosopher in 18th Century Europe". blog.apaonline.org. American Philosophical Association. Retrieved 2 November 2023. Concise account of Amo's life and work.

- Smith, Justin E. H. (23 September 2012). "Anton Wilhelm Amo. An African Philosopher in the German Enlightenment". theamoproject.org. Archived from the original on 4 February 2013. Retrieved 2 November 2023.

Some Early Sources on Amo. Johann Peter von Ludewig (1729): In this very place a baptized Moor by the name of Mister Anton Wilhelm Amo, in the service of His Highness the Duke of Wolfenbüttel, spent some years for the purpose of studying.

An extensive archive of materials by and about Amo.