Anti-Black racism, also called anti-Blackness, colourphobia or negrophobia, is characterised by prejudice, collective hatred, and discrimination or extreme aversion towards people who are racialised as Black people (especially those people from sub-Saharan Africa and its diasporas),[1][2] as well as a loathing of Black culture worldwide. Such sentiment includes, but is not limited to: the attribution of negative characteristics to Black people; the fear, strong dislike or dehumanisation of Black men; and the objectification (including sexual objectification) and dehumanisation of Black women.[3]

First defined by Canadian scholar Dr. Akua Benjamin, the term anti-Black racism (ABR)[4][5] originally described racism towards Black people of African descent, as shaped by slavery and European colonialism.[1][2] However, the term Black can apply more widely to other groups,[6][7][8] including Pacific and non-Atlantic Blacks (or Blaks), such as Indigenous Australians and Melanesians.[9][10] As such, anti-Black racism has since been used to refer to racism against Black people more generally.[9][8][6] The older terms negrophobia and colourphobia[11] were terms created by American abolitionists to describe racism towards people of Black African descent, who were known at the time as Negroes or Coloured.[12][13][14] The term anti-Blackness refers to racism against anyone racialised as Black.[15][16]

Concepts

editTerminology

editAnti-Black racism, sometimes called negrophobia or colourphobia,[12][13] is discriminatory sentiment towards people racialised as Black,[17] often because the person believes that their race is superior to the Black race.[18][19] The terms Afrophobia (or Afriphobia) and melanophobia have also been used.[20][21]

Afrophobia

editAfrophobia, or Afriphobia, is often used to describe racism (particularly systemic racism) against Black people of African descent, such as by the European Network Against Racism (ENAR).[20][22] Others use Afrophobia to describe racism and xenophobia against people of African descent, and against especially indigenous Africans, for their perceived Africanness. This may also include prejudice against African traditions and culture. For example, Afrophobia is used to describe xenophobia in South Africa against people of other African nationalities for being too racially Black, too culturally African, or both.[23]

Anti-Black racism

editAnti-Black racism was a term first used by Canadian scholar Dr. Akua Benjamin in a 1992 report on Ontario race relations. It is defined as follows:

Anti-Black racism is a specific manifestation of racism rooted in European colonialism, slavery and oppression of Black people since the sixteenth century. It is a structure of iniquities in power, resources and opportunities that systematically disadvantages people of African descent.[1]

The term quickly came to be used to refer to racism against other groups also considered Black,[6][8] such as Indigenous Australians (who sometimes prefer the term Blak) and Melanesians.[9][10]

Melanophobia

editMelanophobia has been used to refer to both anti-Black racism[24] and colourism (prejudice against people with darker skin), especially in Latin America, the Middle East, and Africa.[25][26][27]

Negrophobia and colourphobia

editThe term racism is not attested before the 20th century,[28] but negrophobia (first recorded between 1810–1820; often capitalised), and later colourphobia (first recorded in 1834),[29][12] likely originated within the abolitionist movement, where it was used as an analogy to rabies (then called hydrophobia) to describe the "mad dog" mindset behind the pro-slavery cause and its apparently contagious nature.[13][30][31][32] In 1819, the term was used in U.S. Congressional debates to refer to a "violent aversion or hatred of Negroes".[33]

The term negrophobia may also have been inspired by the word nigrophilism, itself first appearing in 1802 in Baudry des Lozières's Les égarements du nigrophilisme.[34] Noting the shift of -phobia terms to cover prejudice and hatred rather than mere fear or aversion, J. L. A. Garcia refers to negrophobia as "the granddaddy of these ‘-phobia’ terms", preceding both xenophobia and homophobia.[31]

Both at the time, and since, critics of the terms negrophobia and colourphobia have argued that, although their use of -phobia is rhetorical, if taken literally they could be used to excuse or justify the behaviour of racists as mental illness or disease. John Dick, publisher of The North Star, voiced such concerns as early as 1848 while legal scholar Jody David Armour has voiced similar concerns in the 21st century.[31][35] Nevertheless, negrophobia had a clinical and satirical edge that made it popular with abolitionists.[31][32] In 1856, abolitionist Harriet Beecher Stowe published Dred: A Tale of the Great Dismal Swamp, a novel which explored the fear of Blackness within negrophobia via the titular character Dred, a Black revolutionary Maroon.[36]

Changing terminology

editAfter abolition, negrophobia continued to be used to refer to anti-Black racism, but terms based on race also appeared around the turn of the 20th century. Racism first appeared in print in 1903.[37] In December 1921, the terms negrophobia and race hatred were used to describe an outbreak of anti-Black violence in the Dominican Republic by John Sydney de Bourg, a spokesman for the local chapter of the Universal Negro Improvement Association in San Pedro de Macorís.[38] Negrophobia further reappeared in January 1927 in Lamine Senghor's La voix des nègres (The Voice of the Negroes), a monthly anti-colonialist newspaper. The term became more widespread outside of North America and the English-speaking world when French Caribbean psychologist and philosopher Frantz Fanon included it in his works Peaux noires masques blancs (Black Skin, White Masks) and Les Damnés de la Terre (The Wretched of the Earth), again drawing on the rhetoric of racism as disease.[34][39] As a psychiatrist, Fanon explored negrophobia as an individual and societal "neurosis", although he saw it as the psychological structure underpinning colonial racism.[40][41][42]

By the middle of the 20th century, the term "Black" came to be preferred over "Negro", and so related terms became outdated.[14] However, negrophobia is still sometimes used to distinguish anti-Black racism from racism more generally. In this sense, Negrophobia may mean an especially strong, violent or transmissible form of anti-Black racism. In France, Une Autre Histoire describes negrophobia as meaning "the most virulent form of racism targeting those who are perceived as 'blacks' by people considering themselves different from 'blacks'" (translation).[34] Adia A. Brooks, who developed the Multidimensional Negrophobia Index (MNI) to measure anti-Black racism, describes it as a "thought system, or ideology" and "the profound fear or hatred of black people and black culture".[43]

Psychology

editPsychologists and sociologists have explored the individual and social psychology of anti-Black racism, often in reference to Fanon's work on negrophobia. Jock McCulloch explores Fanon's conception from a psychodynamic perspective, arguing that negrophobia requires psychological projection, and reveals "a certain psychic dependence of the European upon the black". He also points out that negrophobia, though it can be described as an emotional disorder, is theorised to come from the same "psychodynamic mechanism" as antisemitism, and stresses the importance, in Fanon's account, of negrophobia as inherently racist and a product of colonialism.[44][45] Despite this, the description of negrophobia as an emotional disorder or involuntary reflex has been used as a legal defense to justify violent crimes against Black people,[35] including murder, as a form of self-defense or involuntary reaction.[46][47][48]

Internalised racism

editPsychiatrist Frantz Fanon introduced the concept of internalised racism, or internalised negrophobia, pointing to the hatred of Black people and Black culture by Black people themselves.[3] He asserts that anti-Black sentiment is a form of "trauma for white people of the Negro".[49] Equivalent to internalised racism caused by the trauma of living in a culture defining Black people as inherently evil, Fanon emphasises the slight existing cultural intricacies caused by the vast diversity of Black people and cultures, as well as the nature of their colonisation by White Europeans.[3] The symptoms of such internalised anti-Black sentiment include a rejection of their native or ethnic language in favour of European languages, a marked preference for European cultures over Black cultures, and a tendency to surround themselves with lighter-skinned people rather than darker-skinned ones.[3]

Similarly, the pattern further includes attributing negative characteristics to Black people, culture, and things. Toni Morrison's novel The Bluest Eye (1970) stands as an illustrative work on the destroying effects of anti-Black sentiment among the Black community on themselves.[50] The main character, Pecola Breedlove, through her non-reconciliation with her Black identity, her Black societal indifference, and her craving for symbolic blue eyes, presents all the signs of an internalised anti-Black sentiment.[50] She develops an anti-Black neurosis due to her feeling of non-existence both within the White and her own community.[50]

While the latter theoretical framework is academically debated, Fanon insists on the nature of anti-Black sentiment as a socio-diagnosis, thus characterising not individuals but rather entire societies and their patterns.[3] Fanon thereby implies that anti-Black sentiment is a cross-disciplinary area of research, justifying that its analysis and understanding may not be confined to the psychological field.[3]

Involuntary racism

editIn the book Negrophobia and Reasonable Racism, legal scholar Jody David Armour describes the term Involuntary Negrophobia as the legal precedent of defendants using a victim's Blackness as justification for violent crimes against them.[51] Typically, such arguments rest on the idea that racist revulsion and violence directed at Black people is an involuntary reaction, such as with PTSD, and thus not an intentional criminal act; or that it constitutes a form of self-defence based on their perception of the victim as a threat because of their Blackness. This approach focusses on the personal culpability of the individual defendant, and their state of mind. Armour critiques this view as equating anti-Black sentiment with insanity and allowing a person's racial fear to legally justify and even excuse violent behaviour.[51][46]

Education and business

editIn response to Black Lives Matter organising contemporary scholars have begun focusing on anti-Blackness in educational institutions[52][53][54] and places of business.[55][56] These efforts build on established critical race discourses in their respective fields and incorporate concepts from Afropessimism.[57][page needed]

Anti-Black racism globally

editAfrica

editMauritania

editSlavery in Mauritania persists despite its abolition in 1980 and mostly affects the descendants of black Africans abducted into slavery who now live in Mauritania as "black Moors" or haratin and who partially still serve the "white Moors", or bidhan, as slaves. The practice of slavery in Mauritania is most dominant within the traditional upper class of the Moors. For centuries, the haratin lower class, mostly poor black Africans living in rural areas, have been considered natural slaves by these Moors. Social attitudes have changed among most urban Moors, but in rural areas, the ancient divide remains.[58]

The ruling bidanes are descendants of the Sanhaja Berbers and Beni Ḥassān Arab tribes who emigrated to northwest Africa and present-day Western Sahara and Mauritania during the Middle Ages. Many descendants of the Beni Ḥassān tribes today still adhere to the supremacist ideology of their ancestors, which has caused the oppression, discrimination and even enslavement of other groups in Mauritania.[59]

According to some estimates, as many as 600,000 black Mauritanians, or 20% of the population, are still enslaved, many of them used as bonded labour.[60] Slavery in Mauritania was criminalized in August 2007.[61]South Africa

editCape Coloureds

editMixed-race people in South Africa are referred to as Coloureds or Cape Coloureds. This term includes individuals with a mixed-race descent that can include African, Asian, and European ethnic heritage.[66] The term "Coloured" is considered neutral in South African society and is commonly used to refer to individuals who self-identify as such.[67] However, in some Western countries, such as the United Kingdom and the United States, the term "Coloured" has a negative connotation and can be seen as derogatory because it was historically used as a means of categorising Black individuals and reinforcing racial hierarchies.[68] The word persists as a neutral descriptor in the names of some older organizations, such as the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) in the United States.

The 1911 South African census played a significant role in shaping the country's racial identities. The enumeration process involved specific instructions for classifying individuals into different racial categories, and the category of "Coloured persons" was used to refer to all people of mixed race. This included various ethnicities, such as Khoikhoi, San, Cape Malays, Griquas, Korannas, Creoles, Negroes, and Cape Coloureds. What is particularly noteworthy about the classification of "Coloured persons" is that it included individuals of Black African descent, who were commonly known as Negroes. As a result, Coloureds or Cape Coloureds, as a group of mixed-race descent individuals, also have Black African ancestry and can be considered part of the broader African diaspora.[69]

The racial category of Coloureds is a multifaceted and heterogeneous group that exhibits great diversity. Analogously, they can be compared to Black Americans, whose population is composed of approximately 75% West African and 25% Northern European ancestry. However, the Cape Coloureds possess an even greater level of complexity due to the presence of Bantu ancestry in their genetic makeup, which is closely linked to the predominantly West African heritage of Black Americans.[70][71]

While Coloureds in South Africa do have Black African ancestry, it is important to recognize that they have a distinct identity and experiences that differ from those of Black South Africans. Despite this, there are instances where Coloureds may face discrimination and prejudice based on their mixed-race descent and Black African ancestry. Furthermore, some individuals who hold prejudiced attitudes towards Black people may also hold negative attitudes towards Coloureds, viewing them as inferior or less desirable due to their mixed-race heritage.

Asia

editIndia

editIncidents of violence against African students in India are widespread with some being widely covered by local, national and international media.[72][73] These include the murder of a 29 year old Congolese national, Masonda Ketada Olivier, in May 2016, who was beaten to death by 3 men in South Delhi over a fight about hiring an auto rickshaw.[74] This incident triggered widespread condemnation from African students in India, the African Heads of Mission in New Delhi, along with local backlash against Indian minorities in the Congo.[75] In March 2015, 4 men from the Ivory Coast were assaulted by a mob in the city of Bangalore.[76] In 2020, in Uttarakhand's Roorkee Institute of Technology, 2 African students, Ibrahim a Nigerian-Guinean and Benjamin a Ghanaian were attacked by a group of security guards, with Ibrahim being dragged from the second to the ground floor and Benjamin being hit by bamboo sticks. This incident led to the arrest of the Director of the institution along with 7 other individuals.[77]

Following incidents of violence, the Delhi police in 2017 created a special helpline for Africans residing in the National Capital Region as part of their outreach program to assure them of their safety and security.[78]

African students in India are stereotyped as drug dealers, prostitutes, or even cannibals.[73] In one incident in Greater Noida in 2017, the African students in the city faced violence and hostility following the death of Manish Khari, a class 12 student. The locals suspected the students of cannibalism and blamed them for his death, police arrested 5 students following local pressure, however released them subsequently as no evidence was found against them. The police had to request the students to stay indoors until their safety could be guaranteed and made arrests for the racial violence, however the local unit of the BJP and Hindu Yuva Vahini petitioned the police to stop making any further arrests among those booked for the incidents.[79]Israel

editIn April 2012, the Swedish newspaper Svenska Dagbladet reported that tens of thousands of refugees and African migrant workers who have come to Israel in dangerous smuggling routes, live in southern Tel Aviv's Levinsky Park. SvD reported that some Africans in the park sleep on cardboard boxes under the stars, others crowd in dark hovels. Also was noted a situation with African refugees, such as Sudanese from Darfur, Eritreans, Ethiopians and other African nationalities, who stand in queue to the soup kitchen, organized by Israeli volunteers. The interior minister reportedly "wants everyone to be deported".[80]

In May 2012, disgruntlement toward Africans and calls for deportation and "blacks out" in Tel Aviv boiled over into death threats, fire bombings, rioting, and property destruction. Protesters blamed immigrants for worsening crime and the local economy, some of protesters were seen throwing eggs at African immigrants[81][82]

In March 2018, chief Sephardic Rabbi of Israel, Yitzhak Yosef, used the term Kushi to refer to black people, which has Talmudic origins but is a derogatory word for people of African descent in modern Hebrew. He also reportedly likened black people to monkeys.[83][84][85]Japan

editSaudi Arabia

editEurope

editIn Europe, anti-Black sentiment finds its roots in the 17th century due to its extensive historical colonisation and slavery.[34]

France

editIn 2005, an anti-negrophobia brigade (BAN) was created in France to protest against increasing numbers of targeted acts and occurrences of police violence against Black people.[34] The latter protest movements notably underwent severe police violence in the Jardin du Luxembourg in Paris during the 2011 and 2013 abolition of slavery commemorations.[34]

United Kingdom

editThis section needs to be updated. The reason given is: Should cover African migrants and post-1960s too. (December 2024) |

Black immigrants who arrived in Britain from the Caribbean in the 1950s faced racism. For many Caribbean immigrants, their first experience of discrimination came when trying to find private accommodation. They were generally ineligible for council housing because only people who had been resident in the UK for a minimum of five years qualified for it. At the time, there was no anti-discrimination legislation to prevent landlords from refusing to accept black tenants. A survey undertaken in Birmingham in 1956 found that only 15 of a total of 1,000 white people surveyed would let a room to a black tenant. As a result, many black immigrants were forced to live in slum areas of cities, where the housing was of poor quality and there were problems of crime, violence and prostitution.[90][91] One of the most notorious slum landlords was Peter Rachman, who owned around 100 properties in the Notting Hill area of London. Black tenants sometimes paid twice the rent of white tenants, and lived in conditions of extreme overcrowding.[90]

Historian Winston James suggests that the experience of racism in Britain was a major factor in the development of a shared Caribbean identity amongst black immigrants from a range of different island and class backgrounds.[92]

In the 1970s and 1980s, black people in Britain were the victims of racist violence perpetrated by far-right groups such as the National Front.[93] During this period, it was also common for Black footballers to be subjected to racist chanting from crowd members.[94][95]

Racism in Britain in general, including against black people, is considered to have declined over time. Academic Robert Ford demonstrates that social distance, measured using questions from the British Social Attitudes survey about whether people would mind having an ethnic minority boss or have a close relative marry an ethnic minority spouse, declined over the period 1983–1996. These declines were observed for attitudes towards Black and Asian ethnic minorities. Much of this change in attitudes happened in the 1990s. In the 1980s, opposition to interracial marriage were significant.[96][97] Nevertheless, Ford says:

Racism and racial discrimination remain a part of everyday life for Britain's ethnic minorities. Black and Asian Britons...are less likely to be employed and are more likely to work in worse jobs, live in worse houses and suffer worse health than White Britons.[96]

The University of Maryland's Minorities at Risk (MAR) project noted in 2006 that while African-Caribbeans in the United Kingdom no longer face formal discrimination, they continue to be under-represented in politics, and to face discriminatory barriers in access to housing and in employment practices. The project also says that the British school system "has been indicted on numerous occasions for racism, and for undermining the self-confidence of black children and maligning the culture of their parents". The MAR profile on African-Caribbeans in the United Kingdom suggests "growing 'black on black' violence between people from the Caribbean and immigrants from Africa".[98] Martin Hewitt of the Metropolitan Police has said that murders using knives are given insufficient public attention because most victims are black people from London.[99][100]

A 2014 study by the Black Training and Enterprise Group (BTEG), funded by Trust for London, explored the views of young Black males in London on why their demographic have a higher unemployment rate than any other group of young people. According to participants, racism and negative stereotyping were the main reasons for their high unemployment rate.[101] In 2021, 67% of Black 16 to 64-year-olds were employed, compared to 76% of White British and 69% of British Asians. The employment rate for Black 16 to 24-year-olds was 31%, compared to 56% of White British and 37% of British Asians.[102] The median hourly pay for Black Britons in 2021 was amongst the lowest out of all ethnicity groups at £12.55, ahead of only British Pakistanis and Bangladeshis.[103] In 2023, the Office for National Statistics published more granular analysis and found that UK-born black employees (£15.18) earned more than UK-born white employees (£14.26) in 2022, while non-UK born black employees earned less (£12.95). Overall, black employees had a median hourly pay of £13.53 in 2022.[104]

A 2023 University of Cambridge survey which featured the largest sample of Black people in Britain found that 88% had reported racial discrimination at work, 79% believed the police unfairly targeted black people with stop and search powers and 80% definitely or somewhat agreed that racial discrimination was the biggest barrier to academic attainment for young Black students.[105]North America

editCanada

editIn a 2013 survey of 80 countries by the World Values Survey, Canada ranked among the most racially tolerant societies in the world.[106] Nevertheless, according to Statistics Canada's Ethnic Diversity Survey, released in September 2003, when asked about the five-year period from 1998 to 2002 nearly one-third (32 per cent) of respondents who identified as Black reported that they had been subjected to some form of racial discrimination or unfair treatment "sometimes" or "often".[107]

From the late 1970s to the early 1990s, a number of unarmed Black Canadian men in Toronto were shot or killed by Toronto Police officers.[108][109] In response, the Black Action Defence Committee (BADC) was founded in 1988. BADC's executive director, Dudley Laws, stated that Toronto had the "most murderous" police force in North America, and that police bias against blacks in Toronto was worse than in Los Angeles.[109][110] In 1990, BADC was primarily responsible for the creation of Ontario's Special Investigations Unit, which investigates police misconduct.[109][111] Since the early 1990s, the relationship between Toronto Police and the city's black community has improved;[109] in 2015, Mark Saunders became the first black police chief in the city's history. Carding remained an issue as of 2016;[112] restrictions against arbitrary carding came into effect in Ontario in 2017.[113]

Throughout the years, high-profile cases of racism against Black Canadians have occurred in Nova Scotia.[114][115][116] The province continues to champion human rights and battle against racism, in part by an annual march to end racism against people of African descent.[117][118]

Black ice hockey players in Canada have reported being victims of racism.[119][120][121]Dominican Republic

editRacism in the Dominican Republic exists due to the after-effects of African slavery and the subjugation of black people throughout history. In the Dominican Republic, "blackness" is often associated with Haitian migrants and a lower class status. Those who possess more African-like phenotypic features are often victims of discrimination, and are seen as foreigners.[122]

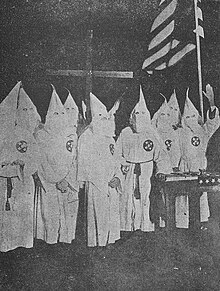

United States

editIn the context of racism in the United States, racism against African Americans dates back to the colonial era, and it continues to be a persistent issue in American society in the 21st century.

From the arrival of the first Africans in early colonial times until after the American Civil War, most African Americans were enslaved. Even free African Americans have faced restrictions on their political, social, and economic freedoms, being subjected to lynchings, segregation, Black Codes, Jim Crow laws, and other forms of discrimination, both before and after the Civil War. Thanks to the civil rights movement, formal racial discrimination was gradually outlawed by the federal government, and gradually came to be perceived as socially and morally unacceptable by large elements of American society. Despite this, racism against Black Americans remains widespread in the U.S., as does socioeconomic inequality between black and white Americans.[a][125] In 1863, two years prior to emancipation, Black people owned 0.5 percent of the national wealth, while in 2019 it is just over 1.5 percent.[126]

In recent years research has uncovered extensive evidence of racial discrimination in various sectors of modern U.S. society, including the criminal justice system, businesses, the economy, housing, health care, the media, and politics. In the view of the United Nations and the US Human Rights Network, "discrimination in the United States permeates all aspects of life and extends to all communities of color."[127]Oceania

editAustralia

editAfrican Australians

editSouth America

editBrazil

editMany Brazilians still think that race impacts life in their country. A research article published in 2011 indicated that 63.7% of Brazilians believe that race interferes with the quality of life, 59% believe it makes a difference at work, and 68.3% in questions related to police justice. According to Ivanir dos Santos (the former Justice Ministry's specialist on race affairs), "There is a hierarchy of skin color: where blacks, mixed race and dark skinned people are expected to know their place in society."[130] Although 54% of the population is black or has black ancestry, they represented only 24% of the 513 chosen representatives the legislature as of 2018.[131]

For many decades, discussions of inequality in Brazil largely ignored the disproportionate correlation between race and class. Under the racial democracy thesis, it was assumed that any disparity in wealth between white and non-white Brazilians was due to the legacy of slavery and broader issues of inequality and lack of economic mobility in the country. The general consensus was that the problem would fix itself given enough time. This hypothesis was examined in 1982 by sociologist José Pastore in his book Social Mobility in Brazil. In his book, Pastore examines the 1973 household survey and compares the income and occupations of father-son pairs. Based on his findings, he concluded that the level of economic mobility in Brazil should have been enough to overcome inequality left from slavery had opportunities been available equally.[132]

Racial inequality is seen primarily through lower levels of education and income for non-whites than whites.[133] Economic inequality is most dramatically seen in the near absence of non-whites from the upper levels of Brazil's income bracket. According to sociologist Edward Telles, whites are five times more likely to be earning in the highest income bracket (more than $2,000/month).[134] Overall, The salary of Whites in Brazil are, on average, 46% over the salary of Blacks.[130]

Additionally, racial discrimination in education is a well documented phenomenon in Brazil. Ellis Monk, Professor of sociology at Harvard University, found that one unit of darkness in a student's skin corresponds to a 26 percent lower chance of the student receiving more education as compared to lighter-skinned students.[133] Further, a study on racial bias in teacher evaluations in Brazil found that Brazilian math teachers gave better grading assessments of white students than equally proficient and equivalently well-behaved black students.[135]

Quality of Life Indicators vs. Race

| Indicators | White Brazilian | Black & Multiracial Brazilian |

|---|---|---|

| Illiteracy[136] | 3.4% | 7.4% |

| University degree[137] | 15.0% | 4.7% |

| Life expectancy[138] | 76 | 73 |

| Unemployment[139] | 6.8% | 11.3% |

| Average annual income[140][141] | R$37,188 | R$21,168 |

| Homicide deaths[142] | 29% | 65.5% |

Racism against non-African Black people

editThough anti-Black racism traditionally refers to people of Black African descent, there are other groups who are identified as Black and whose experiences of racism may share similarities to those of Black Africans.[1][9] These groups include Indigenous Australians (Aboriginal Australians and Torres Strait Islanders) and Melanesians.

Indigenous Australians

editIndigenous peoples of Australia, comprising Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders peoples, have lived in Australia for at least 65,000 years[143][144] before the arrival of the First Fleet in 1788. The colonisation of Australia and development into a modern nation, saw explicit and implicit racial discrimination against Indigenous Australians.

Indigenous Australians continue to be subjected to racist government policy and community attitudes. Racist community attitudes towards Aboriginal people have been confirmed as continuing both by surveys of Indigenous Australians[145] and self-disclosure of racist attitudes by non-Indigenous Australians.[146]

Since 2007, government policy considered to be racist include the Northern Territory Intervention which failed to produce a single child abuse conviction,[147] cashless welfare cards trialled almost exclusively in Aboriginal communities,[148] the Community Development Program that has seen Indigenous participants fined at a substantially higher rate than non-Indigenous participants in equivalent work-for-the-dole schemes,[149] and calls to shut down remote Indigenous communities[150] despite the United Nation's Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples specifying governments must facilitate the rights of Indigenous people to live on traditional land.

In 2016, police raids and behaviour on Palm Island following a death in custody were found to have breached the Racial Discrimination Act 1975,[151] with a record class action settlement of $30 million awarded to victims in May 2018.[152] The raids were found by the court to be "racist" and "unnecessary, disproportionate" with police having "acted in these ways because they were dealing with an Aboriginal community."[151]Melanesians

editAustralia

editTens of thousands of South Sea Islanders were kidnapped from islands nearby to Australia and sold as slaves to work on the colony's agricultural plantations through a process known as blackbirding.

This trade in what were then known as Kanakas was in operation from 1863 to 1908, a period of 45 years. Some 55,000 to 62,500 were brought to Australia,[153] most being recruited or blackbirded from islands in Melanesia, such as the New Hebrides (now Vanuatu), the Solomon Islands and the islands around New Guinea.

The majority of those taken were male and around one quarter were under the age of sixteen.[154] In total, approximately 15,000 South Sea Islander slaves died while working in Queensland, a figure which does not include those who died in transit or who were killed in the recruitment process. This represents a mortality rate of at least 30%, which is high considering most were only on three year contracts.[155] It is also similar to the estimated 33% death rate of enslaved Africans in the first three years of being taken to America.[156]

The trade was legally sanctioned and regulated under Queensland law, and prominent men such as Robert Towns made massive fortunes off of exploitation of slave labour, helping to establish some of the major cities in Queensland today.[157] Towns' agent claimed that blackbirded labourers were "savages who did not know the use of money" and therefore did not deserve cash wages.[158]

Following Federation in 1901, the White Australia policy came into effect, which saw most foreign workers in Australia deported under the Pacific Island Labourers Act 1901, which saw the Pacific Islander population of the state decrease rapidly.[159]Indonesia

editIn the provinces of Papua and West Papua, the program has resulted in the Papuan population of Melanesian origin totalling less than the population of non-Melanesian (principally Austronesian) origin in several locations. According to Papuan independence activists, the Papuans have lived on the New Guinea island for an estimated 50,000 years,[160] but have been outnumbered in less than 50 years by mostly Javanese Indonesians.[161] They criticize the program as part of "an attempt to wipe out the West Papuans in a slow-motion genocide".[162] There is open conflict between migrants, the state, and indigenous groups due to differences in culture—particularly in administration, and cultural topics such as nudity, food and sex. Religion is also a problem as Papuans are predominantly Christian or hold traditional tribal beliefs while the non-Papuan settlers are mostly Muslim. A number of Indonesians have taken Papuan children and sent them to Islamic religious schools.[163]

The recorded population growth rates in Papua are exceptionally high due to migration.

Detractors[who?] of the program argue that considerable resources have been wasted in settling people who have not been able to move beyond subsistence level, with extensive damage to the environment and deracination of tribal people. However, very large scale American and Anglo-Australian strip mining contracts have been developed on the island, as well as other Indonesian islands.

The transmigration program in Papua was only formally halted by President Joko Widodo in June 2015.[164]See also

editNotes

edit- ^ In his 2009 visit to the US, the [UN] Special Rapporteur on Racism noted that "Socio-economic indicators show that poverty, race and ethnicity continue to overlap in the United States. This reality is a direct legacy of the past, in particular, it is a direct legacy of slavery, segregation and the forcible resettlement of Native Americans, which was confronted by the United States during the civil rights movement. However, whereas the country managed to establish equal treatment and non-discrimination in its laws, it has yet to redress the socioeconomic consequences of the historical legacy of racism."[124]

References

edit- ^ a b c d Husbands, Winston; Lawson, Daeria O.; Etowa, Egbe B.; Mbuagbaw, Lawrence; Baidoobonso, Shamara; Tharao, Wangari; Yaya, Sanni; Nelson, LaRon E.; Aden, Muna; Etowa, Josephine (2022-10-01). "Black Canadians' Exposure to Everyday Racism: Implications for Health System Access and Health Promotion among Urban Black Communities". Journal of Urban Health. 99 (5): 829–841. doi:10.1007/s11524-022-00676-w. ISSN 1468-2869. PMC 9447939. PMID 36066788.

- ^ a b Dryden, OmiSoore; Nnorom, Onye (2021-01-11). "Time to dismantle systemic anti-Black racism in medicine in Canada". CMAJ. 193 (2): E55 – E57. doi:10.1503/cmaj.201579. ISSN 0820-3946. PMC 7773037. PMID 33431548.

- ^ a b c d e f Brooks, Adia A. (2012). "Black Negrophobia and Black Self-Empowerment: Afro-Descendant Responses to Societal Racism in São Paulo, Brazil" (PDF). UW-L Journal of Undergraduate Research. XV: 2. Retrieved 4 May 2020.

- ^ Rakotovao, Lucina; Simeoni, Michelle; Bennett-AbuAyyash, Caroline; Walji, Taheera; Abdi, Samiya (2024-06-28). "Addressing anti-Black racism within public health in North America: a scoping review". International Journal for Equity in Health. 23 (1): 128. doi:10.1186/s12939-024-02124-4. ISSN 1475-9276. PMC 11212177. PMID 38937746.

- ^ Gregory, Virgil L.; Clary, Kelly Lynn (2022-01-02). "Addressing Anti-Black Racism: The Roles of Social Work". Smith College Studies in Social Work. 92 (1): 1–27. doi:10.1080/00377317.2021.2008287. ISSN 0037-7317.

- ^ a b c MacMaster, Neil (2001), MacMaster, Neil (ed.), "Anti-Black Racism in an Age of Total War", Racism in Europe 1870–2000, London: Macmillan Education UK, pp. 117–139, doi:10.1007/978-1-4039-4033-9_5, ISBN 978-1-4039-4033-9, retrieved 2024-07-21

- ^ Library, Web. "Guides: Anti-Black Racism: Definitions and Introductory Texts". libraryguides.mcgill.ca. Retrieved 2024-07-21.

- ^ a b c Shilliam, Robbie (2015). The Black Pacific: Anti-Colonial Struggles and Oceanic Connections (1 ed.). Bloomsbury Publishing Plc. doi:10.5040/9781474218788.ch-003. ISBN 978-1-4742-1878-8.

- ^ a b c d Barwick, Daniel; Nayak, Anoop (2024-07-08). "The Transnationalism of the Black Lives Matter Movement: Decolonization and Mapping Black Geographies in Sydney, Australia". Annals of the American Association of Geographers. 114 (7): 1587–1603. doi:10.1080/24694452.2024.2363782. ISSN 2469-4452.

- ^ a b Fredericks, Bronwyn; Bradfield, Abraham (2021-04-27). "'I'm Not Afraid of the Dark': White Colonial Fears, Anxieties, and Racism in Australia and Beyond". M/C Journal. 24 (2). doi:10.5204/mcj.2761. ISSN 1441-2616.

- ^ Gemeinhardt, April (2016-01-01). ""The Most Poisonous of All Diseases of Mind or Body": Colorphobia and the Politics of Reform". Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers.

- ^ a b c "Colourphobia | Colorphobia, N., Etymology." Oxford English Dictionary, Oxford UP, July 2023, https://doi.org/10.1093/OED/9131678901.

- ^ a b c "Negrophobia, N., Etymology." Oxford English Dictionary, Oxford UP, July 2023, https://doi.org/10.1093/OED/5704106894.

- ^ a b “Negro, N. & Adj.” Oxford English Dictionary, Oxford UP, March 2024, https://doi.org/10.1093/OED/2341880472.

- ^ "Anti-black, Adj." Oxford English Dictionary, Oxford UP, December 2023, https://doi.org/10.1093/OED/7595464650.

- ^ "Anti-blackness, N." Oxford English Dictionary, Oxford UP, March 2024, https://doi.org/10.1093/OED/4777283713.

- ^ The Congregational Review, Volume 2. J.M. Whittemore. 1862. p. 629. Retrieved 10 December 2015.

- ^ Hankela 2014, p. 88.

- ^ Berwanger, Eugene H. (1972). "Negrophobia in Northern Proslavery and Antislavery Thought". Phylon. 33 (3): 266–275. doi:10.2307/273527. ISSN 0031-8906. JSTOR 273527.

- ^ a b Privot, M., 2014. Afrophobia and the ‘Fragmentation of Anti-racism.’. Visible Invisible Minority: Confronting Afrophobia and Advancing Equality for People of African Descent and Black Europeans in Europe, pp.31-38.

- ^ Chinweizu, C., 2003. Afrocentric Rectification of Terms: Excerpt from: What Slave Trade? And other Afrocentric reflections on the Race War. TINABANTU: Journal of Advanced Studies of African Society, 1(2).

- ^ Momodou, J. and Pascoët, J., 2014. Towards a European strategy to combat Afrophobia. European Network Against Racism, Invisible visible minority: Confronting Afrophobia and advancing equality for people of African descent and Black Europeans in Europe, pp.262-272.

- ^ Koenane, M.L.J. and Maphunye, K.J., 2015. Afrophobia, moral and political disguises: Sepa leholo ke la moeti. Td: The Journal for Transdisciplinary Research in Southern Africa, 11(4), pp.83-98.

- ^ Biale, D., Galchinsky, M. and Heschel, S. eds., 1998. Insider/outsider: American Jews and multiculturalism. Univ of California Press.

- ^ Madden, R., 2006. Tez de mulato. Colonialism and Race in Luso-Hispanic Literature, p.114.

- ^ Torres-Saillant, S., 2003. Inventing the race: Latinos and the ethnoracial pentagon. Latino Studies, 1, pp.123-151.

- ^ Mirmotahari, E., 2015. A Cloud of Semitic Mohammedanism: The African Novel and the Muslim Question in the National Age. Interventions, 17(1), pp.45-63.

- ^ "Definition of RACISM". www.merriam-webster.com. Retrieved 2024-07-20.

- ^ "Definition of COLORPHOBIA". www.merriam-webster.com. Retrieved 2024-07-20.

- ^ "Dictionary.com | Meanings & Definitions of English Words". Dictionary.com. Retrieved 2024-07-20.

- ^ a b c d Garcia, J. L .A. "Racism and the Discourse of Phobias: Negrophobia, Xenophobia and More---Dialogue with Kim and Sundstrom". SUNY Open Access Repository. p. 2. Retrieved 2024-07-03.

- ^ a b "The Anti-Slavery Roots of Today's "-Phobia" Obsession". The New Republic. ISSN 0028-6583. Retrieved 2024-07-20.

- ^ "Negrophobia | Etymology of Negrophobia by etymonline". www.etymonline.com. Retrieved 2024-07-20.

- ^ a b c d e f Une Autre Histoire (13 January 2015). "Négrophobie". une-autre-histoire.org. Retrieved 6 May 2020.

- ^ a b Armour, Jody David (1997), "Introduction: ʺRATIONALʺ DISCRIMINATION AND THE BLACK TAX", Negrophobia and Reasonable Racism, The Hidden Costs of Being Black in America, NYU Press, p. 2, JSTOR j.ctt9qfpg3.4, retrieved 2024-07-20

- ^ McLaughlin, Don James (2019). "Dread: The Phobic Imagination in Antislavery Literature". J19: The Journal of Nineteenth-Century Americanists. 7 (1): 21–48. doi:10.1353/jnc.2019.0001. ISSN 2166-7438.

- ^ “Racism, N.” Oxford English Dictionary, Oxford UP, July 2023, https://doi.org/10.1093/OED/1101660185.

- ^ Wright, Micah (2015-04-03). "An Epidemic of Negrophobia: Blackness and the Legacy of the US Occupation of the Dominican Republic". The Black Scholar. 45 (2): 21–33. doi:10.1080/00064246.2015.1012994. ISSN 0006-4246.

- ^ Brooks, Adia A. (2012). "Black Negrophobia and Black Self-Empowerment: Afro-Descendant Responses to Societal Racism in São Paulo, Brazil" (PDF). UW-L Journal of Undergraduate Research. XV: 2. Retrieved 4 May 2020.

- ^ Yokum, N. (2024). "A call for psycho-affective change: Fanon, feminism, and white negrophobic femininity." Philosophy & Social Criticism, 50(2), 343-368. https://doi.org/10.1177/01914537221103897

- ^ Sandra Lee Bartky, Femininity and Domination: Studies in the Phenomenology of Oppression (New York: Routledge, 1990), p. 22.

- ^ Mary Ann Doane, "Dark Continents: Epistemologies of Racial and Sexual Difference in Psychoanalysis and the Cinema", in Femmes Fatales: Feminism, Film Theory, and Psychoanalysis (New York: Routledge, 2013/1991: 209–248), 217.

- ^ Brooks, Adia A. (2012). "Black Negrophobia and Black Self-Empowerment: Afro-Descendant Responses to Societal Racism in São Paulo, Brazil" (PDF). UW-L Journal of Undergraduate Research. Retrieved 2024-07-03.

- ^ McCulloch, Jock (16 May 2002). Black Soul, White Artifact: Fanon's Clinical Psychology and Social Theory. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-52025-6. pp. 72–3. 233.

- ^ Burman, E. (2016). "Fanon’s Lacan and the Traumatogenic Child: Psychoanalytic Reflections on the Dynamics of Colonialism and Racism." Theory, Culture & Society, 33(4), 77-101. https://doi.org/10.1177/0263276415598627

- ^ a b Armour, Jody D. (1994). "Race Ipsa Loquitur: Of Reasonable Racists, Intelligent Bayesians, and Involuntary Negrophobes". Stanford Law Review. 46 (4): 781–816. doi:10.2307/1229093. ISSN 0038-9765. JSTOR 1229093.

- ^ Hill, Brandon (2014-08-29). "Negrophobia: Michael Brown, Eric Garner, and America's Fear of Black People". TIME. Retrieved 2024-07-03.

- ^ Bauerlein, Mark (2001). Negrophobia: A Race Riot in Atlanta, 1906. Encounter Books. ISBN 978-1-893554-23-8. p. 3, 238.

- ^ Anthony C. Alessandrini (3 August 2005). Frantz Fanon: Critical Perspectives. Routledge. p. 153. ISBN 978-1-134-65657-8.

- ^ a b c Maleki, Nasser and Haj'jari and Mohammad-Javad (2015). "Negrophobia and Anti-Negritude in Morrison's The Bluest Eye". Epiphany: Journal of Transdisciplinary Studies. 8: 69. Retrieved 7 May 2020.

- ^ a b Armour, Jody David (1997). Negrophobia and Reasonable Racism: The Hidden Costs of Being Black in America. NYU Press. JSTOR j.ctt9qfpg3. pp. 64–5.

- ^ Bell, Myrtle P.; Berry, Daphne; Leopold, Joy; Nkomo, Stella (January 2021). "Making Black Lives Matter in academia: A Black feminist call for collective action against anti-blackness in the academy". Gender, Work & Organization. 28 (S1): 39–57. doi:10.1111/gwao.12555. hdl:2263/85604. ISSN 0968-6673. S2CID 224844343.

- ^ Dumas, Michael J.; ross, kihana miraya (April 2016). ""Be Real Black for Me": Imagining BlackCrit in Education". Urban Education. 51 (4): 415–442. doi:10.1177/0042085916628611. ISSN 0042-0859. S2CID 147319546.

- ^ Dumas, Michael J. (2016-01-02). "Against the Dark: Antiblackness in Education Policy and Discourse". Theory into Practice. 55 (1): 11–19. doi:10.1080/00405841.2016.1116852. ISSN 0040-5841. S2CID 147252566.

- ^ Bohonos, Jeremy W (July 2023). "Workplace hate speech and rendering Black and Native lives as if they do not matter: A nightmarish autoethnography". Organization. 30 (4): 605–623. doi:10.1177/13505084211015379. ISSN 1350-5084. S2CID 236294224.

- ^ Bohonos, Jeremy W.; Sisco, Stephanie (June 2021). "Advocating for social justice, equity, and inclusion in the workplace: An agenda for anti-racist learning organizations". New Directions for Adult and Continuing Education. 2021 (170): 89–98. doi:10.1002/ace.20428. ISSN 1052-2891. S2CID 240576110.

- ^ Wilderson 2021.

- ^ Fletcher, Pascal (21 March 2007). "Slavery still exists in Mauritania". Reuters News. Reuters. Retrieved 17 June 2015.

- ^ "IRIN Africa - MAURITANIA: Fair elections haunted by racial imbalance - Mauritania - Governance - Human Rights". IRINnews. 2007-03-05. Retrieved 17 June 2015.

- ^ "BBC World Service - The Abolition season on BBC World Service". Retrieved 17 June 2015.

- ^ "BBC NEWS - Africa - Mauritanian MPs pass slavery law". 2007-08-09. Retrieved 17 June 2015.

- ^ a b c d Houston, Gregory (2022). "Racial Privilege in Apartheid South Africa". In Houston, Gregory; Kanyane, Modimowabarwa; Davids, Yul Derek (eds.). Paradise Lost: Race and Racism in Post-apartheid South Africa. Africa-Europe Group for Interdisciplinary Studies. Vol. 28. Leiden and Boston: Brill Publishers. pp. 35–72. doi:10.1163/9789004515949_003. ISBN 978-90-04-51594-9. ISSN 1574-6925.

- ^ a b c d e f Bradshaw, Debbie; Norman, Rosana; Laubscher, Ria; Schneider, Michelle; Mbananga, Nolwazi; Steyn, Krisela (2004). "Chapter 19: An Exploratory Investigation into Racial Disparities in the Health of Older South Africans". In Anderson, N. B.; Bulatao, R. A.; Cohen, B. (eds.). Critical Perspectives on Racial and Ethnic Differences in Health in Late Life. Washington, D.C.: National Academies Press on behalf of the National Research Council Panel on Race, Ethnicity, and Health in Later Life. pp. 703–736. doi:10.17226/11086. ISBN 978-0-309-16570-9. PMID 20669464. NBK25536.

- ^ a b c "Race in South Africa: 'We haven't learnt we are human beings first'". BBC News. London. 21 January 2021. Archived from the original on 5 November 2022. Retrieved 10 November 2022.

- ^ Kaziboni, Anthony (2022). "Apartheid Racism and Post-apartheid Xenophobia: Bridging the Gap". In Rugunanan, Pragna; Xulu-Gama, Nomkhosi (eds.). Migration in Southern Africa: IMISCOE Regional Reader. IMISCOE Research Series. Cham, Switzerland: Springer Nature. pp. 201–213. doi:10.1007/978-3-030-92114-9_14. ISBN 978-3-030-92114-9. ISSN 2364-4095.

- ^ Kline Jr. 1958, p. 8254.

- ^ Stevenson & Waite 2011, p. 283.

- ^ "Is the word 'coloured' offensive?". BBC News. 9 November 2006. Retrieved 5 June 2019.

- ^ Moultrie, Tom A.; Dorrington, Rob E. (August 2012). "Used for ill; used for good: a century of collecting data on race in South Africa". Ethnic and Racial Studies. 35 (8): 1447–1465. doi:10.1080/01419870.2011.607502.

- ^ Khan, Razib (June 16, 2011). "The Cape Coloureds are a mix of everything". Discover. Retrieved March 2, 2023.

- ^ Christopher, A. J. (2002). "'To Define the Indefinable': Population Classification and the Census in South Africa". Area. 34 (4): 401–408. Bibcode:2002Area...34..401C. doi:10.1111/1475-4762.00097. ISSN 0004-0894. JSTOR 20004271.

- ^ "A grim reality". The Indian Express. 2016-05-30. Retrieved 2023-01-26.

- ^ a b "'We are scared' _ Africans in India say racism is constant". AP NEWS. 2016-06-10. Retrieved 2023-01-26.

- ^ "29-year-old Congolese man killed in Delhi, police probe racism angle". Hindustan Times. 2016-05-21. Retrieved 2023-01-26.

- ^ "Shops of Indians in Congo attacked after murder of African man in Delhi". Hindustan Times. 2016-05-26. Retrieved 2023-01-26.

- ^ "4 Africans Allegedly Attacked by Mob in Bengaluru". NDTV.com. Retrieved 2023-01-26.

- ^ Quint, The (2020-07-16). "2 African Students Brutalised in Roorkee College, Director Nabbed". TheQuint. Retrieved 2023-01-26.

- ^ "Police launch special helpline for Africans living in India". The Indian Express. 2017-03-30. Retrieved 2023-01-26.

- ^ "'Africans Are Cannibals,' and Other Toxic Indian Tales". The Wire. Retrieved 2023-01-26.

- ^ Bitte Hammargren (28 April 2012). "Israel vill utvisa afrikanska immigranter". Svenska Dagbladet (in Swedish). Retrieved 2012-07-08.

- ^ Sheera Frenkel (24 May 2012). "Violent Riots Target African Nationals Living In Israel". NPR.

- ^ Gilad Morag (28 May 2012). "Video: Israeli hurls egg at African migrant". Ynet.

- ^ Surkes, Sue (20 March 2018). "Chief rabbi calls black people 'monkeys'". The Times of Israel. Retrieved 15 May 2018.

- ^ Kra-Oz, Tal (14 May 2018). "Israeli Chief Rabbi Calls African Americans 'Monkeys'". The Tablet. Retrieved 22 March 2018.

- ^ Cohen, Hayley (21 March 2018). "ADL Slams Chief Rabbi of Israel for Calling Black People 'Monkeys'". Haaretz. Retrieved 14 May 2018.

- ^ Reicheneker, Sierra (January 2011). "The Marginalization of Afro-Asians in East Asia: Globalization and the Creation of Subculture and Hybrid Identity". Global Tides. 5 (1). Retrieved 4 July 2012.

The products of both prostitution and legally binding marriages, these children were largely regarded as illegitimate. When the military presence returned to America, the distinction between the two was, for all practical purposes, null. As the American military departed, any previous preferential treatment for biracial people ended and was replaced with a backlash due to the return of ethnically-based national pride.

- ^ "Middle East :: SAUDI ARABIA". CIA The World Factbook. 14 November 2023.

- ^ "The New Arab – Dark-skinned and beautiful: Challenging Saudi Arabia's perception of beauty". 8 March 2017.

- ^ "46 Saudis marry African women". 7 December 2015.

- ^ a b Cloake, J. A.; Tudor, M. R. (2001). Multicultural Britain. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 38–39. ISBN 978-0199134243.

- ^ Phillips, Deborah; Karn, Valerie (1991). "Racial Segregation in Britain: Patterns, Processes, and Policy Approaches". In Huttman, Elizabeth D. (ed.). Urban Housing Segregation of Minorities in Western Europe and the United States. Durham, NC: Duke University Press. pp. 63–91. ISBN 978-0822310600.

- ^ James, Winston (1992). "Migration, Racism and Identity: The Caribbean Experience in Britain" (PDF). New Left Review. I/193: 15–55.

- ^ Small, Stephen (1994). Racialised Barriers: The Black Experience in the United States and England in the 1980s. Abingdon: Routledge. p. 76. ISBN 978-0415077262.

- ^ "Racism and football fans". Social Issues Research Centre. Archived from the original on 9 May 2015. Retrieved 28 April 2015.

- ^ Holland, Brian (1995). "'Kicking racism out of football': An assessment of racial harassment in and around football grounds". Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies. 21 (4): 567–586. doi:10.1080/1369183X.1995.9976513.

- ^ a b Ford, Robert (2008). "Is racial prejudice declining in Britain?". The British Journal of Sociology. 59 (4): 609–636. doi:10.1111/j.1468-4446.2008.00212.x. PMID 19035915.

- ^ Ford, Rob (21 August 2014). "The decline of racial prejudice in Britain". University of Manchester. Archived from the original on 4 May 2015. Retrieved 28 April 2015.

- ^ "Assessment for Afro-Caribbeans in the United Kingdom". Minorities at Risk Project, University of Maryland. 31 December 2006. Archived from the original on 22 November 2014. Retrieved 28 April 2015.

- ^ Slawson, Nicola (21 March 2018), "Knife deaths among black people 'should cause more outrage'", The Guardian. Archived 22 March 2018 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ "Police: Are black knife deaths being ignored?", BBC, 21 March 2018. Archived 6 May 2018 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ "Action Plan to Increase Employment Rates for Young Black Men in London". trustforlondon.org.uk. Archived from the original on 18 May 2015. Retrieved 2 December 2014.

- ^ "Ethnicity facts and figures: Employment". gov.uk. Office for National Statistics. 3 November 2022. Retrieved 26 May 2023.

- ^ "Ethnicity fact and figures: Average hourly pay". gov.uk. Office for National Statistics. 27 July 2022.

- ^ "Ethnicity pay gaps, UK: 2012 to 2022". Office for National Statistics. Retrieved 29 November 2023.

- ^ "Black British Voices: the findings". University of Cambridge. 28 September 2023.

- ^ Fisher, Max (15 May 2013). "A fascinating map of the world's most and least racially tolerant countries". Washington Post. Retrieved 26 February 2023.

- ^ "Statistics Canada". Statcan.ca. 26 September 2003. Retrieved 22 January 2011.

- ^ Philip Mascoll, "Sherona Hall, 59: Fighter for justice", Toronto Star, 9 January 2007

- ^ a b c d James, Royson (25 March 2011). "James: Dudley Laws stung and inspired a generation". thestar.com. Retrieved 26 February 2023.

- ^ K. K. Campbell, "LAWS CHARGES METRO POLICE BIAS AGAINST BLACKS `WORSE THAN L.A.' Archived 3 February 2011 at the Wayback Machine" Eye Weekly, 1 October 1992

- ^ Winsa, Patty (24 March 2011). "'Fearless' black activist Dudley Laws dies at age 76". thestar.com. Retrieved 26 February 2023.

- ^ Gillis, Wendy (1 January 2016). "Police chief Mark Saunders claims he is not afraid of change — and assures it's coming in 2016". thestar.com. Retrieved 26 February 2023.

- ^ Draaisma, Muriel (1 January 2017). "New Ontario rule banning carding by police takes effect". CBC News. Retrieved 26 February 2023.

- ^ Moore, Oliver (24 February 2010). "This page is available to GlobePlus subscribers". The Globe and Mail. Toronto. Retrieved 26 July 2010.

- ^ Lowe, Lezlie (29 January 2009). "Halifax's hidden racism". The Coast Halifax. Retrieved 26 February 2023.

- ^ Discrimination Against Blacks in Nova Scotia: The Criminal Justice System, by Wilson A. Head; Donald H. J. Clairmont; Royal Commission on the Donald Marshall, Jr., Prosecution (N.S.) State or province government publication, Publisher: [Halifax, N.S.] : The Commission, 1989.

- ^ "BreakingNews – Protest targets racism in Halifax". TheSpec.com. 23 February 2010. Retrieved 26 July 2010.[permanent dead link]

- ^ Beltrame, Julian (9 November 1985). "Blacks in Nova Scotia burdened by lingering racism". Ottawa Citizen. p. B6. Retrieved 26 February 2023.

- ^ Harris, Cecil (2003). Breaking the ice : the Black experience in professional hockey. Toronto [Ont.]: Insomniac Press. ISBN 1-894663-58-6.

- ^ Bell, Susan; Longchap, Betsy; Smith, Corinne. "First Nations hockey team subjected to racist taunts, slurs at Quebec City tournament". CBC News. Retrieved 26 February 2023.

- ^ Jeffrey, Andrew; Saba, Rosa (30 November 2019). "Hockey's race problem: Canadian players reflect on racism in the sport they love". thestar.com. Retrieved 26 February 2023.

- ^ Quinn, Rachael Afi (2015). ""No tienes que entenderlo": Xiomara Fortuna, Racism, Feminism, and Other Forces in the Dominican Republic". Black Scholar. 45 (3): 54–66. doi:10.1080/00064246.2015.1060690. S2CID 143035833.

- ^ a b Fisher, Max (May 15, 2013). "Map shows world's 'most racist' countries". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on April 30, 2017. Retrieved April 30, 2017.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - ^ CERD Task Force of the US Human Rights Network (August 2010). "From Civil Rights to Human Rights: Implementing US Obligations Under the International Convention on the Elimination of All forms of Racial Discrimination (ICERD)". Universal Periodic Review Joint Reports: United States of America. p. 44.

- ^ Henry, P. J., David O. Sears. Race and Politics: The Theory of Symbolic Racism. University of California, Los Angeles. 2002.

- ^ "Why the racial wealth gap persists, more than 150 years after emancipation". The Washington Post. Retrieved May 27, 2024.

- ^ U.S. Human Rights Network (August 2010). "The United States of America: Summary Submission to the UN Universal Periodic Review". Universal Periodic Review Joint Reports: United States of America. p. 8.

- ^ Mapedzahama, Virginia; Kwansah-Aidoo, Kwamena (2017). "Blackness as Burden? The Lived Experience of Black Africans in Australia". SAGE Open. 7 (3). SAGE Publications: 1–13. doi:10.1177/2158244017720483. hdl:1959.3/438351. ISSN 2158-2440. pdf Text from this source is available under a Attribution 4.0 International (CC BY 4.0) licence.

- ^ Gatwiri, Kathomi (3 April 2019). "Growing Up African in Australia: Racism, resilience and the right to belong". The Conversation. Retrieved 3 November 2020.

Review: Growing Up African in Australia, edited by Maxine Beneba Clarke, Magan Magan and Ahmed Yussuf

- ^ a b Brazilians Think Race Intefere [sic] on Quality of Life, but not Everyone is Concerned About Equality (in English)

- ^ The Brazilian Report (November 20, 2018). "Ethnic Representation in Brazil's Congress: a long road ahead". The Brazilian Report.

- ^ Pastore, Jose (1982). Social Mobility in Brazil. University of Wisconsin Press.[page needed]

- ^ a b Monk, Ellis P. (August 2016). "The Consequences of "Race and Color" in Brazil". Social Problems. 63 (3): 413–430. doi:10.1093/socpro/spw014. S2CID 6738969.

- ^ Telles 2006, p. 110.

- ^ Botelho, Fernando; Madeira, Ricardo A.; Rangel, Marcos A. (1 October 2015). "Racial Discrimination in Grading: Evidence from Brazil". American Economic Journal: Applied Economics. 7 (4): 37–52. doi:10.1257/app.20140352. S2CID 145711236.

- ^ "Analfabetismo entre negros é mais que o dobro do registrado entre brancos". Folha de S.Paulo (in Brazilian Portuguese). 2023-06-07. Retrieved 2023-07-14.

- ^ Academic degree between Whites and Blacks in Brazil (in Portuguese)

- ^ "A expectativa de vida no Brasil, por gênero, raça ou cor, e estado". www.nexojornal.com.br (in Brazilian Portuguese). Retrieved 2023-07-14.

- ^ "Desemprego é maior entre mulheres e negros, diz IBGE". Agência Brasil (in Brazilian Portuguese). 2023-05-18. Retrieved 2023-07-14.

- ^ "IBGE: renda média de trabalhador branco é 75,7% maior que de pretos". Agência Brasil (in Brazilian Portuguese). 2022-11-11. Retrieved 2023-07-14.

- ^ "Brancos recebem cerca de 70% a mais do que pretos e pardos por hora de trabalho". O Popular (in Brazilian Portuguese). 2022-11-11. Retrieved 2023-07-14.

- ^ http://ultimainstancia.uol.com.br/conteudo/colunas/54059/mais+de+65%25+dos+assassinados+no+brasil+sao+negros.shtml Homicide rate in Brazil (2009) (in Portuguese)]

- ^ Davidson & Wahlquist 2017.

- ^ Wright 2017.

- ^ McGinn, Christine (6 April 2018). "New report reveals extent of online racial abuse towards Indigenous Australians". SBS Australia. Retrieved 4 June 2019.

- ^ "Racism causing mental health issues in Indigenous communities, survey shows". Guardian Australia. 29 July 2014. Retrieved 4 June 2019.

- ^ Pazzano, Chiara (20 June 2012). "Factbox: The 'Stronger Futures' legislation". SBS World News Australia. Archived from the original on 2016-08-16. Retrieved 28 April 2013.

- ^ Gooda, Mick (16 October 2015). "New report reveals extent of online racial abuse towards Indigenous Australians". ABC News. Retrieved 4 June 2019.

- ^ Conifer, Dan (4 October 2018). "Indigenous communities slapped with more fines under Government work-for-the-dole scheme, data shows". ABC News. Retrieved 4 June 2019.

- ^ Griffiths, Emma (11 March 2015). "Indigenous advisers slam Tony Abbott's 'lifestyle choice' comments as 'hopeless, disrespectful'". ABC News. Retrieved 4 June 2019.

- ^ a b "Queensland police breached discrimination act on Palm Island, court finds". Brisbane Times. 5 December 2016. Retrieved 12 May 2018.

- ^ Lily, Nothling (2 May 2018). "Palm Island riots class action payout 'slap in face' to police, union says". The Courier Mail. Retrieved 12 May 2018.

- ^ Tracey Flanagan, Meredith Wilkie, and Susanna Iuliano. "Australian South Sea Islanders: A Century of Race Discrimination under Australian Law" Archived 14 March 2011 at the Wayback Machine, Australian Human Rights Commission.

- ^ Corris, Peter (2013-12-13), Passage, port and plantation: a history of Solomon Islands labour migration, 1870–1914 (Thesis), archived from the original on 27 July 2020, retrieved 5 July 2019

- ^ McKinnon, Alex (July 2019). "Blackbirds, Australia had a slave trade?". The Monthly. p. 44.

- ^ Ray, K.M. "Life Expectancy and Mortality rates". Encyclopedia.com. Gale Library of Daily Life: Slavery in America. Archived from the original on 5 July 2019. Retrieved 5 July 2019.

- ^ Sparrow, Jeff (2022-08-04). "Friday essay: a slave state - how blackbirding in colonial Australia created a legacy of racism". The Conversation. Archived from the original on 27 August 2023. Retrieved 2023-08-27.

- ^ "A fair thing for the Polynesians". The Brisbane Courier. 20 March 1871. p. 7. Retrieved 1 June 2019 – via Trove.

- ^ "Documenting Democracy". Foundingdocs.gov.au. Archived from the original on 26 October 2009. Retrieved 4 August 2010.

- ^ Saltford, J; The United Nations and the Indonesian Takeover of West Papua, 1962-1969, Routledge Curzon, p.3, p.150

- ^ Transmigration in Indonesia: Lessons from Its Environmental and Social Impacts, Philip M Fearnside, Department of Ecology, National Institute for Research in the Amazon, 1997, Springer-Verlag New York Inc. Accessed online 17 November 2014

- ^ "Department of Peace and Conflict Studies" (PDF).

- ^ They're taking our children: West Papua's youth are being removed to Islamic religious schools in Java for "re-education", Michael Bachelard, Sydney Morning Herald, 4 May 2013, accessed 17 November 2014

- ^ Asril, Sabrina (2015). "Jokowi Hentikan Transmigrasi ke Papua". Kompas.com. Retrieved 17 December 2020.

Works cited

edit- Achola, Paul P.W. (1992). "9". In Ndeti, Kivuto; Gray, Kenneth R. (eds.). The Second Scramble for Africa: A Response & a Critical Analysis of the Challenges Facing Contemporary Sub-Saharan Africa. Kenya: Professors World Peace Academy - Kenya. ISBN 978-9966-835-73-4.

- Adem, Seifudein; Mazrui, Ali A. (2 May 2013). Afrasia: A Tale of Two Continents. University Press of America. ISBN 978-0-7618-4772-4.

- Armour, Jody David (1997). Negrophobia and Reasonable Racism: The Hidden Costs of Being Black in America. NYU Press. JSTOR j.ctt9qfpg3.

- Bauerlein, Mark (2001). Negrophobia: A Race Riot in Atlanta, 1906. Encounter Books. ISBN 978-1-893554-23-8.

- Davidson, Helen; Wahlquist, Calla (20 July 2017). "Australian dig finds evidence of Aboriginal habitation up to 80,000 years ago". The Guardian.

- Hankela, Elina (28 May 2014). Ubuntu, Migration and Ministry: Being Human in a Johannesburg Church. BRILL. ISBN 978-90-04-27413-6.

- James, Darius (19 February 2019). Negrophobia: An Urban Parable. New York Review of Books. ISBN 978-1-68137-348-5.

- Klaffke, Pamela (2003). Spree: A Cultural History of Shopping. Arsenal pulp press. ISBN 9781551521435.

- Kline Jr., Hibberd V. B. (1958). "The Union of South Africa". The World Book Encyclopedia. Vol. 17. Chicago, Field Enterprises Educational Corp.

- Lincoln, Abraham (2013). Ball, Terence (ed.). Lincoln: Political writings and speeches. Cambridge: Cambridge university press. ISBN 978-0521897280.

- McCulloch, Jock (16 May 2002). Black Soul, White Artifact: Fanon's Clinical Psychology and Social Theory. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-52025-6.

- Rieger, Jeorg (2013). Religion, Theology, and Class: Fresh Engagements after Long Silence. New Approaches to Religion and Power. Palgrave Macmillan US. ISBN 978-1-137-33924-9.

- Telles, Edward E. (2006). Race in Another America: The Significance of Skin Color in Brazil. Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-12792-7.

- Stevenson, Angus; Waite, Maurice (2011). "Coloured". Concise Oxford English Dictionary: Luxury Edition. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-960111-0.

- Wilderson, Frank B. (28 September 2021). Afropessimism. National Geographic Books. ISBN 978-1-324-09051-9.

- Wolfrum, Rüdiger (7 September 1999). Frowein, Jochen A.; Wolfrum, Rüdiger (eds.). Max Planck Yearbook of United Nations Law. Martinus Nijhoff Publishers. ISBN 978-90-411-9753-5.

- Wright, Tony (20 July 2017). "Aboriginal archaeological discovery in Kakadu rewrites the history of Australia". The Sydney Morning Herald.