The black-footed cat (Felis nigripes), also called the small-spotted cat, is the smallest wild cat in Africa, having a head-and-body length of 35–52 cm (14–20 in). Despite its name, only the soles of its feet are black or dark brown. With its bold small spots and stripes on the tawny fur, it is well camouflaged, especially on moonlit nights. It bears black streaks running from the corners of the eyes along the cheeks, and its banded tail has a black tip.

| Black-footed cat | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | Carnivora |

| Suborder: | Feliformia |

| Family: | Felidae |

| Subfamily: | Felinae |

| Genus: | Felis |

| Species: | F. nigripes

|

| Binomial name | |

| Felis nigripes Burchell, 1824

| |

| |

| Distribution of the black-footed cat in 2016[1] | |

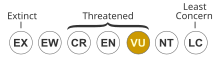

The first black-footed cat known to science was discovered in the northern Karoo of South Africa and described in 1824. It is endemic to the arid steppes and grassland savannas of Southern Africa. It was recorded in southern Botswana, but only a few authentic records exist in Namibia, in southern Angola and in southern Zimbabwe. Due to its restricted distribution, it has been listed as a vulnerable species on the IUCN Red List since 2002. The population is suspected to be declining due to poaching of prey species for human consumption as bushmeat, persecution, traffic accidents, and predation by herding dogs.

The black-footed cat has been studied using radio telemetry since 1993. This research allowed direct observation of its behaviour in its natural habitat. It usually rests in burrows during the day and hunts at night. It moves between 5 and 16 km (3 and 10 mi) on average in search of small rodents and birds. It feeds on 40 different vertebrates and kills up to 14 small animals per night. It can catch birds in flight, jumping up to 1.4 m (5 ft) high, and also attacks mammals and birds much heavier than itself. A female usually gives birth to two kittens during the Southern Hemisphere summer between October and March. They are weaned at the age of two months and become independent after four months of age at the latest.

Taxonomy and phylogeny

editThe scientific name Felis nigripes was used by the British explorer William John Burchell in 1824 when he described the species based on skins of small, spotted cats that he encountered near Litákun (now known as Dithakong), in South Africa.[2] Felis (Microfelis) nigripes thomasi was proposed as a subspecies by the South African mammalogist Guy C. Shortridge in 1931, who described black-footed cat skins collected in Griqualand West that were darker than those of the nominate subspecies.[3] When the British zoologist Reginald Innes Pocock reviewed cat skins in the collection of the Natural History Museum, London, he corroborated that the black-footed cat is a Felis species.[4]

The validity of a subspecies was doubted as no geographical barriers matching the observed differences exist between populations.[5] In 2017, the IUCN Cat Specialist Group revised felid taxonomy and noted that the black-footed cat is most probably a monotypic species.[6]

Phylogeny and evolution

editPhylogenetic analysis of the nuclear DNA from all Felidae species revealed that their evolutionary radiation began in Asia in the Miocene around 14.45 to 8.38 million years ago.[7][8] Analysis of mitochondrial DNA of all Felidae species indicates that they radiated at around 16.76 to 6.46 million years ago.[9]

The black-footed cat is part of an evolutionary lineage that is estimated to have genetically diverged from the common ancestor of all Felis species around 4.44 to 2.16 million years ago, based on analysis of their nuclear DNA.[7][8] Analysis of their mitochondrial DNA indicates a genetic divergence of Felis species at around 6.52 to 1.03 million years ago.[9] Both models agree on the jungle cat (F. chaus) having been the first Felis species that diverged, followed by the black-footed cat.[7][9]

Fossil remains of the black-footed cat have not been found.[8] It possibly migrated during the Pleistocene into Africa.[7] This migration was possibly facilitated by extended periods of low sea levels between Asia and Africa.[9]

The following cladogram shows the phylogenetic relationships of the black-footed cat as derived through analysis of nuclear DNA:[7][8]

|

Characteristics

editThe black-footed cat has tawny fur that is entirely covered with black spots. Its head is darker than the rest of the body but paler above the eyes. Its whiskers are white, and its ears bear grizzled dark brown hairs. On the neck and back, some spots are elongated into stripes. The spots form transverse stripes on the shoulders. The forelegs and the hind legs bear irregular stripes. Its tail is confusedly spotted. The underparts of the feet are black or dark brown.[2][10] The throat rings form black semi-circles that vary in colour from dusky brown to pale rufous and are narrowly edged with rufous. Some individuals have a pure white belly with a tawny tinge where it blends into the tawny colour of the flanks.[11] The ears, eyes and mouth are lined with pale off-white.[12] Two black streaks run from the corners of the eyes across the cheeks. Individuals vary in background colour from sandy and pale ochre to dark ochre.[13] In the northern part of its range, it is lighter than in the southern part, where its spots and bands are more clearly defined. The three rings on the throat are reddish brown to black, with the third ring broken in some individuals.[4][10] The black bands are broad on the upper legs and become narrower towards the paws. The 25 to 30 mm (1.0 to 1.2 in) long guard hairs are gray at the base and have either white or dark tips. The underfur is dense with short and wavy hair.[10] The fur becomes thicker and longer during winter.[12] The pupils of the eyes contract to a vertical slit, like in all Felis species.[4] They are light green to dark yellow.[12]

The black-footed cat is the smallest cat species in Africa.[13][10][14][15] Females measure 33.7–36.8 cm (13.3–14.5 in) in head and body length with a 15.7 to 17 cm (6.2 to 6.7 in) long tail. Males are between 42.5 and 50 cm (16.7 and 19.7 in) with a 15–20 cm (6–8 in) long tail. Its tapering tail is about half the length of the head and body.[13] Its skull is short and round with a basal length of 77–87 mm (3.0–3.4 in) and a width of 38–40 mm (1.5–1.6 in). The ear canal and the openings of the ears are larger than in most Felis species. The cheek teeth are 22–23 mm (0.87–0.91 in) long and the upper carnassials 10 mm (0.4 in) long.[4] It has small pointed ears ranging from 45 to 50 mm (1.8 to 2.0 in) in females and 46 to 57 mm (1.8 to 2.2 in) in males. The hindfoot of females measures maximum 95 mm (3.7 in) and of males maximum 105 mm (4.1 in).[11][10] Its shoulder height is less than 25 cm (9.8 in).[16] Females weigh 1.1–1.65 kg (2.4–3.6 lb) and males 1.6–2.45 kg (3.5–5.4 lb).[17][12]

The African wildcat (Felis lybica) is almost three times as large as the black-footed cat, has longer legs, a longer tail and mostly plain grey fur with less distinct markings. The serval (Leptailurus serval) resembles the black-footed cat in coat colour and pattern, but has proportionately larger ears, longer legs and a longer tail.[18]

Distribution and habitat

editThe black-footed cat is endemic to Southern Africa; its distribution is much more restricted than other small cats in this region.[19] Its range extends from South Africa northward into southern Botswana, where it was recorded in the late 1960s.[11] It has also been recorded in Namibia, extreme southern Angola and southern Zimbabwe. It is unlikely to occur in Lesotho and Eswatini.[1] It inhabits open, arid savannas and semi-arid shrubland in the Karoo and the southwestern Kalahari with short grasses, low bush cover, and scattered clumps of low bush and higher grasses.[11] The mean annual precipitation in this region ranges from 100 to 500 mm (3.9 to 19.7 in).[10][12] In the Drakensberg area, it was recorded at an elevation of 2,000 m (6,600 ft).[10]

Behaviour and ecology

editThe black-footed cat is nocturnal and usually solitary, except when females care for dependent kittens.[11][17] It spends the day resting in hollow termite mounds and dense cover in unoccupied burrows of South African springhare (Pedetes capensis), aardvark (Orycteropus afer), and Cape porcupine (Hystrix africaeaustralis). It digs vigorously to extend or modify these burrows for shelter. After sunset, it emerges to hunt.[5] It seeks refuge at the slightest disturbance and often uses termite mounds for cover or for bearing its young. When cornered, it defends itself fiercely. Due to this habit and its courage, it is called miershooptier in parts of the South African Karoo, meaning 'anthill tiger'. A San legend claims that a black-footed cat can kill a giraffe by piercing its jugular. This exaggeration is intended to emphasize its bravery and tenacity.[20]

Unlike most other cats, it is a poor climber, as its stocky body and short tail are thought not to be conducive for climbing trees.[21] However, one black-footed cat was observed and photographed resting in the lower branches of a camelthorn tree (Vachellia erioloba).[22]

A female roams in an average home range of 6.23–15.53 km2 (2.41–6.00 sq mi) in a year, and a resident male in an area of 19.44–23.61 km2 (7.51–9.12 sq mi). The range of an adult male overlaps the ranges of one to four females. It uses scent marking throughout its range.[17] Receptive females were observed spraying urine up to 41 times in a stretch of 685 m (2,250 ft). They sprayed less frequently during pregnancy.[23] Other forms of scent marking include rubbing objects, raking with claws, and depositing faeces in visible locations. Its calls are louder than those of other cats of its size, presumably to allow calls to be heard over relatively large distances. When close to each other, however, it uses quieter purrs or gurgles; when threatened, it hisses and growls.[17] Adults move an average of 8.42 ± 2.09 km (5.23 ± 1.30 mi) per night in search of prey.[24] It is difficult to survey because of its highly secretive nature; moreover, it tends to move fast without using roads or tracks like other cats. In South Africa, a density of 0.17/km2 (0.44/sq mi) was estimated in Benfontein near Kimberley during 1998 to 1999, that fell to 0.08/km2 (0.2/sq mi) during 2005 to 2014. Farther south, in the Nuwejaarsfontein area, the estimated number of individuals during 2009 to 2014 was 0.06/km2 (0.16/sq mi). These were probably exceptionally high densities, as both areas feature good weather and management conditions, while the number of individuals in less favourable habitats could be closer to 0.03/km2 (0.08/sq mi).[1]

Hunting and diet

editThe black-footed cat hunts at night irrespective of the weather, at temperatures from −10 to 35 °C (14 to 95 °F). It attacks its prey from the rear, puts its forepaws on its flanks and grounds the prey using its dewclaws. It employs three different ways of hunting: "fast hunt", "slow hunt", and "sit and wait" hunt. In a fast hunt, it moves at a speed of 2 to 3 km/h (1.2 to 1.9 mph) and chases prey out of vegetation cover. During a slow hunt, it stalks the prey at a speed of 0.5 to 0.8 km/h (0.3 to 0.5 mph), meandering cautiously through the grass and vigilantly checking its surroundings while turning its head side to side.[5] It moves between 5 and 16 km (3 and 10 mi) on average in search of small rodents and birds, mostly moving in small circles and zig-zagging among bushes and termite mounds.[25] In a "sit and wait" hunt, it waits for the prey motionlessly in front of a rodent den, sometimes with closed eyes. Its ears keep moving, and it opens the eyes as soon as it hears a sound.[5]

Due to its small size, the black-footed cat hunts mainly small prey such as rodents and small birds, but also preys on Cape hare (Lepus capensis), being heavier than itself. Its energy requirement is very high, with about 250 to 300 g (9 to 11 oz) of prey consumed per night, which is about a sixth of its average body weight.[26] It is able to satisfy its daily water requirements through its prey, but drinks water when available.[12]

Black-footed cats have been observed to attempt catching 10 vertebrates in five hours of hunting, with a mean of six successful attempts.[5] In 1993, a female and a male black-footed cat were followed for 622 hours and observed hunting. They caught vertebrates every 50 minutes and killed up to 14 small animals in a night. They killed shrews and rodents by a bite in the neck or in the head and consumed them completely. They stalked birds quietly, followed by a quick chase and a jump up to a height of 1.4 m (4 ft 7 in) and over a distance of 2 m (6 ft 7 in), also catching some in the air. They pulled them down to the ground and consumed small birds like Cape clapper lark (Mirafra apiata) and spike-heeled lark (Chersomanes albofasciata) without plucking. They plucked large birds like northern black korhaan (Afrotis afraoides), ate for several hours, cached the remains in hollows and covered them with sand.[25] Neonate springbok (Antidorcas marsupialis) lambs keep hiding quietly in a hollow or under a bush for the first few days of their lives.[27] A male pounced on a lamb resting in the grass, but abandoned the hunt after the lamb got up on its feet. It later scavenged the carcass of a recently deceased lamb weighing nearly 3 kg (6.6 lb). It consumed around 120 g (0.26 lb) meat in each of several bouts of eating, starting from the thighs, making its way from the lower back through the flanks to the neck; later it opened up the chest and fed on the inner organs. Insects like harvester termites, grasshoppers and moths constituted about 2% of the prey mass consumed.[25] Altogether 54 prey species of the black-footed cat were identified, with the gerbil mouse (Malacothrix typica) being among its most important prey. Its average prey weighs 24.1 g (0.85 oz) with small mammals constituting the most important prey class, followed by larger mammals weighing more than 100 g (3.5 oz) and small birds.[28]

Reproduction and life cycle

editIn captivity, male black-footed cats become sexually mature at the age of nine months, and females at the age of seven months.[5] Their oestrus lasts around 36 hours, and gestation lasts 63 to 68 days.[29] The female gives birth to up to two litters per year during the Southern Hemisphere summer between October and March. The litter size is usually one or two kittens, in rare cases also four kittens.[5]

Wild female black-footed cats observed in the wild were receptive to mating for only five to ten hours, requiring males to locate them quickly. Males fight for access to the female. Copulation occurs nearly every twenty to fifty minutes.[17]

Kittens weigh 60 to 93 g (2.1 to 3.3 oz) at birth; they are born blind and relatively helpless, although they are able to crawl after just a few hours. Their eyes open at three to ten days, and their deciduous teeth break through at the age of two to three weeks. Within one month, they take solid food, and are weaned at the age of two months. Their permanent teeth erupt at the age of 148 to 158 days.[5]

Captive females were observed trying to shift their kittens to a new hiding place every six to ten days after a week of their birth, much more frequently than other small cats. They are able to walk within two weeks and start climbing at three weeks.[29] In the wild, kittens are born in South African springhare burrows or hollow termite mounds. From the age of four days onward, the mother leaves her kittens alone for up to 10 hours during nights. At the age of six weeks, they can move fast and frequently leave the den. Kittens and independent subadults are at the risk of falling prey to other carnivores such as black-backed jackal (Canis mesomelas), caracal (Caracal caracal) and nocturnal raptors.[30] They become independent after three to four months and tend to stay within their mother's home range. Captive black-footed cats can live for up to 15 years and three months.[12]

Diseases

editBoth captive and free-ranging black-footed cats exhibit a high prevalence of AA amyloidosis, which causes chronic inflammatory processes and usually culminates in kidney failure and death.[5][31] Wild black-footed cats are susceptible to transmission of infectious diseases from domestic dogs and cats.[32]

Threats

editKnown threats include methods of indiscriminate predator control, such as bait poisoning and steel-jaw traps, habitat destruction from overgrazing, declining South African springhare populations, intraguild predation, diseases, and unsuitable farming practices. Several black-footed cats have been killed by herding dogs. The majority of protected areas may be too small to adequately conserve viable sub-populations.[1]

Conservation

editThe black-footed cat is listed on CITES Appendix I and is protected throughout most of its range including Botswana and South Africa, where hunting is illegal.[1]

Field research

editThe Black-footed Cat Working Group carries out a research project at Benfontein Nature Reserve and Nuwejaarsfontein Farm near Kimberley, Northern Cape.[33] In November 2012, this project was extended to Biesiesfontein Farm located in the Victoria West area.[34] Between 1992 and 2018, 65 black-footed cats were radio-collared and followed for extended periods to improve the understanding about their social organisation, sizes and use of their home ranges, hunting behaviour and composition of their diet.[35] Camera traps are used to monitor the behaviour of radio-collared black-footed cats and their interaction with aardwolves (Proteles cristatus).[36]

In captivity

editThe Wuppertal Zoo acquired black-footed cats in 1957, and succeeded in breeding them in 1963. In 1993, the European Endangered Species Programme was formed to coordinate which animals are best suited for pairing to maintain genetic diversity and to avoid inbreeding. The International Studbook for the Black-footed Cat was kept in the Wuppertal Zoo in Germany.[37] As of July 2011[update], detailed records existed for a total of 726 captive cats since 1964; worldwide, 74 individuals were kept in 23 institutions in Germany, United Arab Emirates, US, UK, and South Africa.[38]

Several zoos reported breeding successes, including Cleveland Metroparks Zoo,[39] Fresno Chaffee Zoo,[40] Brookfield Zoo,[41] and Philadelphia Zoo.[42]

The Audubon Nature Institute's Center for Research of Endangered Species is working on advanced genetics involving cats.[43] In February 2011, a female kept there gave birth to two male kittens – the first black-footed cats to be born as a result of in vitro fertilization using frozen and thawed sperm and frozen and thawed embryos. In 2003, the sperm was collected from a male and then frozen. It was used to fertilize an egg in 2005, creating embryos that were thawed and transferred to a surrogate female in December 2010. The female carried the embryos to term and gave birth to two kittens.[44] The same center reported that on 6 February 2012, a female black-footed cat kitten, Crystal, was born to a domestic cat surrogate after interspecies embryo transfer.[45]

References

edit- ^ a b c d e f g Sliwa, A.; Wilson, B.; Küsters, M.; Tordiffe, A. (2020) [errata version of 2016 assessment]. "Felis nigripes". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2016: e.T8542A177944648. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2016-1.RLTS.T8542A177944648.en. Retrieved 15 January 2022.

- ^ a b Burchell, W. J. (1824). "Felis nigripes". Travels in the Interior of Southern Africa. Vol. II. London: Longman, Hurst, Rees, Orme, Brown, and Green. p. 592. Archived from the original on 19 July 2023. Retrieved 29 April 2020.

- ^ Shortridge, G. C. (1931). "Felis (Microfelis) nigripes thomasi subsp. nov". Records of the Albany Museum. 4 (1): 119–120.

- ^ a b c d Pocock, R. I. (1951). "Felis nigripes Burchell". Catalogue of the genus Felis. London: British Museum (Natural History). pp. 145–150.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Olbricht, G. & Sliwa, A. (1997). "In situ and ex situ observations and management of black-footed cats Felis nigripes". International Zoo Yearbook. 35 (35): 81–89. doi:10.1111/j.1748-1090.1997.tb01194.x.

- ^ Kitchener, A. C.; Breitenmoser-Würsten, C.; Eizirik, E.; Gentry, A.; Werdelin, L.; Wilting, A.; Yamaguchi, N.; Abramov, A. V.; Christiansen, P.; Driscoll, C.; Duckworth, J. W.; Johnson, W.; Luo, S.-J.; Meijaard, E.; O’Donoghue, P.; Sanderson, J.; Seymour, K.; Bruford, M.; Groves, C.; Hoffmann, M.; Nowell, K.; Timmons, Z. & Tobe, S. (2017). "A revised taxonomy of the Felidae: The final report of the Cat Classification Task Force of the IUCN Cat Specialist Group" (PDF). Cat News (Special Issue 11): 13. Archived (PDF) from the original on 30 July 2018. Retrieved 16 March 2019.

- ^ a b c d e Johnson, W. E.; Eizirik, E.; Pecon-Slattery, J.; Murphy, W. J.; Antunes, A.; Teeling, E. & O'Brien, S. J. (2006). "The late miocene radiation of modern Felidae: A genetic assessment". Science. 311 (5757): 73–77. Bibcode:2006Sci...311...73J. doi:10.1126/science.1122277. PMID 16400146. S2CID 41672825. Archived from the original on 4 October 2020. Retrieved 29 August 2020.

- ^ a b c d Werdelin, L.; Yamaguchi, N.; Johnson, W. E. & O'Brien, S. J. (2010). "Phylogeny and evolution of cats (Felidae)". In Macdonald, D. W. & Loveridge, A. J. (eds.). Biology and Conservation of Wild Felids. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press. pp. 59–82. ISBN 978-0-19-923445-5. Archived from the original on 25 September 2018. Retrieved 3 May 2020.

- ^ a b c d Li, G.; Davis, B. W.; Eizirik, E. & Murphy, W. J. (2016). "Phylogenomic evidence for ancient hybridization in the genomes of living cats (Felidae)". Genome Research. 26 (1): 1–11. doi:10.1101/gr.186668.114. PMC 4691742. PMID 26518481.

- ^ a b c d e f g Mills, M. G. L. (2005). "Felis nigripes Burchell, 1824 (Black-footed cat)". In Skinner, J. D.; Chimimba, C. T. (eds.). The Mammals of the Southern African Subregion (3rd ed.). Cape Town: Cambridge University Press. pp. 405–408. ISBN 978-0521844185.

- ^ a b c d e Smithers, R. N. H. (1971). "Felis nigripes Blackfooted Cat". The Mammals of Botswana. Pretoria: University of Pretoria. pp. 128–130.

- ^ a b c d e f g Sliwa, A. (2013). "Felis nigripes Black-footed cat". In Kingdon, J.; Happold, D.; Hoffmann, M.; Butynski, T.; Happold, M.; Kalina, J. (eds.). Mammals of Africa. Vol. V. Carnivores, Pangolins, Equids and Rhinoceroses. London, New Delhi, New York, Sydney: Bloomsbury. pp. 203–206. ISBN 978-1-4081-8994-8.

- ^ a b c Guggisberg, C. A. W. (1975). "Black-footed Cat Felis nigripes (Burchell, 1842)". Wild Cats of the World. New York: Taplinger Publishing. pp. 40–42. ISBN 978-0-8008-8324-9.

- ^ Sunquist, M. & Sunquist, F. (2002). "Black-footed cat Felis nigripes (Burchell, 1824)". Wild Cats of the World. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. pp. 75–82. ISBN 0-226-77999-8. Archived from the original on 21 December 2022. Retrieved 8 January 2024.

- ^ Renard, A.; Lavoie, M.; Pitt, J. A. & Larivière, S. (2015). "Felis nigripes (Carnivora: Felidae)". Mammalian Species. 47 (925): 78–83. doi:10.1093/mspecies/sev008.

- ^ Pringle, J.A. (1977). "The distribution of mammals in Natal. Part 2. Carnivora" (PDF). Annals of the Natal Museum. 23 (1): 93–115.

- ^ a b c d e Sliwa, A. (2004). "Home range size and social organization of black-footed cats (Felis nigripes)". Mammalian Biology. 69 (2): 96–107. doi:10.1078/1616-5047-00124.

- ^ Hunter, L. (2015). "Black-footed Cat". Wild Cats of the World. London: Bloomsbury Publishing. pp. 30–33. ISBN 978-1-4729-2285-4. Archived from the original on 8 January 2024. Retrieved 5 November 2020.

- ^ Nowell, K. & Jackson, P. (1996). "Black-footed cat, Felis nigripes Burchell, 1824". Wild Cats Status Survey and Conservation Action Plan. Gland, Switzerland: IUCN Cat specialist Group. pp. 8–10.

- ^ Sliwa, A. (November 2006). "Atomic Kitten: the secrets of Africa's black-footed cat". BBC Wildlife. Vol. 24, no. 12. pp. 36–40.

- ^ Armstrong, J. (1977). "The development and hand-rearing of black-footed cats". In Eaton, R. L. (ed.). The World's Cats: The Proceedings of an International Symposium. Vol. 3. Oregon: Winston Wildlife Safari. pp. 71–80.

- ^ Sliwa, A. (2013). "Black-footed Lightning". Africa Geographic. No. June. pp. 27–31.

- ^ Molteno, A.; Sliwa, A. & Richardson, P. R. K. (1998). "The role of scent marking in a free-ranging, female black-footed cat (Felis nigripes)". Journal of Zoology. 245 (1): 35–41. doi:10.1111/j.1469-7998.1998.tb00069.x.

- ^ Sliwa, A.; Herbst, M. & Mills, M. (2010). "Black-footed cats (Felis nigripes) and African wild cats (Felis silvestris): A comparison of two small felids from South African arid lands". In Macdonald, D. & Loveridge, A. (eds.). The Biology and Conservation of Wild Felids. Oxford University Press. pp. 537–558. ISBN 9780199592838.

- ^ a b c Sliwa, A. (1994). "Diet and feeding behaviour of the Black-footed Cat (Felis nigripes Burchell, 1824) in the Kimberley Region, South Africa". Der Zoologische Garten N.F. 64 (2): 83–96.

- ^ Sliwa, A. (1994). "Black-footed cat studies in South Africa". Cat News (20): 15–19.

- ^ Bigalke, R.C. (1972). "Observations on the behaviour and feeding habits of the springbok, Antidorcas marsupialis". African Zoology. 7 (1): 333–359. doi:10.1080/00445096.1972.11447448. Archived from the original on 27 July 2020. Retrieved 20 May 2020.

- ^ Sliwa, A. (2006). "Seasonal and sex-specific prey composition of black-footed cats Felis nigripes". Acta Theriologica. 51 (2): 195–204. doi:10.1007/BF03192671. S2CID 46729038.

- ^ a b Leyhausen, P. & Tonkin, B. (1966). "Breeding the black-footed cat (Felis nigripes) in captivity". International Zoo Yearbook. 6 (6): 178–182. doi:10.1111/j.1748-1090.1966.tb01744.x.

- ^ Sliwa, A. (1996). "Pleasures and Worries of a Black-Footed Cat Field Study in South Africa". Cat Times. 23: 1–3.

- ^ Terio, K.A.; O’Brien, T.; Lamberski, N.; Famula, T. R. & Munson, L. (2008). "Amyloidosis in black-footed cats (Felis nigripes)". Veterinary Pathology Online. 45 (3): 393–400. doi:10.1354/vp.45-3-393. PMID 18487501. S2CID 43387363.

- ^ Lamberski, N.; Sliwa, A.; Wilson, B.; Herrick, J. & Lawrenz, A. (2009). "Conservation of black-footed cats (Felis nigripes) and prevalence of infectious diseases in sympatric carnivores in the Northern Cape Province, South Africa". In Wibbelt, G.; Kretzschmar, P.; Hofer, H. & Seet, S. (eds.). Proceedings of the International Conference on Diseases of Zoo and Wild Animals 2009: May 20th – 24th, 2009, Beekse Bergen. Berlin: Leibniz-Institut für Zoo- und Wildtierforschung. pp. 243–245.

- ^ Sliwa, A.; Wilson, B. & Lawrenz, A. (2010). Report on surveying and catching black-footed cats (Felis nigripes) on Nuwejaarsfontein Farm / Benfontein Nature Reserve, 4–20 July 2010 (PDF) (Report). Black-footed Cat Working Group. Archived (PDF) from the original on 27 July 2020. Retrieved 30 April 2020.

- ^ Sliwa, A.; Wilson, B.; Lamberski, N. & Lawrenz, A. (2013). Report on surveying, catching and monitoring black-footed cats (Felis nigripes) on Benfontein Nature Reserve, Nuwejaarsfontein Farm, and Biesiesfontein in 2012 (PDF) (Report). Black-footed Cat Working Group. Archived (PDF) from the original on 27 July 2020. Retrieved 30 April 2020.

- ^ Sliwa, A. (2018). "25 years of Black-footed Cat Felis nigripes field research and conservation". In Appel, A.; Mukherjee, S.; Cheyne, S. M. (eds.). Proceedings of the First International Small Wild Cat Conservation Summit, 11–14 September 2017, United Kingdom. Bad Marienberg, Germany; Coimbatore, India; Oxford, United Kingdom: Wild Cat Network, Sálim Ali Centre for Ornithology and Natural History, Borneo Nature Foundation. pp. 7–8.

- ^ Sliwa, A.; Wilson, B.; Lawrenz, A.; Lamberski, N.; Herrick, J. & Küsters, M. (2018). "Camera trap use in the study of black-footed cats (Felis nigripes)". African Journal of Ecology. 56 (4): 895–897. Bibcode:2018AfJEc..56..895S. doi:10.1111/aje.12564. S2CID 92801273.

- ^ Olbricht, G. & Schürer, U. (1994). International Studbook for the Black-footed Cat 1994. Zoologischer Garten der Stadt Wuppertal.

- ^ Stadler, A. (2011). International studbook for the black-footed cat (Felis nigripes). Vol. 15. Zoologischer Garten der Stadt Wuppertal.

- ^ "Press Release: Animal News : Second Litter of Black Footed Cats". Cleveland Metroparks Zoo. 2012. Archived from the original on 20 September 2013.

- ^ Condoian, L. (2011). "General Meeting of the Board of Directors" (PDF). FresnoChaffeeZoo.org. Fresno Chaffee Zoo Corporation. Archived from the original (PDF) on 14 November 2011.

- ^ Katzen, S. (2012). "Black-footed cats born: A first at Brookfield Zoo". Chicago Zoological Society. Archived from the original on 31 March 2012.

- ^ Rearick, K. (2014). "Philadelphia Zoo visitors 'paws' to gush over black-footed cat kittens". South Jersey Times. Archived from the original on 14 July 2014. Retrieved 10 June 2014.

- ^ Jeffries, A. (2013). "Where cats glow green: Weird feline science in New Orleans". The Verge. Archived from the original on 21 January 2018. Retrieved 30 August 2017.

- ^ Burnette, S. (2011). "Rare cats born through amazing science at Audubon Center for Research of Endangered Species". AudubonInstitute.org. Audubon Nature Institute. Archived from the original on 18 February 2014.

- ^ Waller, M. (2012). "Audubon center in Algiers logs another breakthrough in genetic engineering of endangered cats". NOLA.com. New Orleans Net. Archived from the original on 20 January 2018.

External links

edit- "Black-footed Cat Working Group". Wild Cat Network.

- "Felis nigripes". IUCN/SSC Cat Specialist Group.

- "Felis nigripes". Animal Info.

- "Documentary: Meet the Deadliest Cat on the Planet". Nature on PBS. 25 October 2018.

- "Documentary: Black-footed cats". Wildlife Wonder. 18 May 2015.