Mauscheln, also Maus or Vierblatt,[1] is a gambling card game that resembles Tippen, which is commonly played in Germany and the countries of the old Austro-Hungarian Empire.

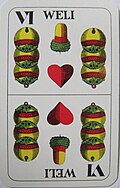

The Weli may be used as the 2nd highest trump | |

| Origin | Austria, Germany |

|---|---|

| Type | Plain-trick |

| Family | Rams group |

| Players | 3 - 5 |

| Age range | 16+ |

| Cards | 32 |

| Deck | William Tell or German-suited pack |

| Rank (high→low) | A K O U 10 9 8 7 or A K Q J 10 9 8 7 |

| Play | Clockwise |

| Related games | |

| Contra, Kratzen, Lupfen, Mistigri, Tippen, Zwicken | |

| Features: pot, 4 cards, optional special trumps | |

Background

editOrigin of the name

editThe name Mauscheln means something like "(secretive) talk". According to Meyers Konversationslexikon of 1885 to 1892 the word Mauschel is derived from the Hebrew word moscheh "Moses", in Ashkenazi Hebrew Mausche, Mousche, and was a nickname for Jews; in Old German mauscheln means something like "speak with a Jewish accent" or haggle".[2] The word first surfaced in the 17th century.[3] Today mauscheln is a synonym for "scheme", "wheel and deal", "wangle" or "diddle".[4]

Other names for the game include Anschlagen (in Tyrol and Lower Austria[5]), Polish Bank (Polnische Bank, not to be confused with another game of this name) or Panczok, also Kratzen,[6] or Frische Vier (in Lower Austria, Styria and Burgenland[5]) or Frische Viere (in South Bohemia in the early 20th century).[7] It also used to be known as Angehen.[8]

The 3-card game, Dreiblatt or Tippen, is very similar to Mauscheln.

History

editMauscheln was clearly current in the early 19th century because it is banned in the Austro-Hungarian Empire as a gambling game in 1832. It is described as popular in many places in the Styria where it was said to be very similar to the forbidden game of Zwicken or Laubiren. The law goes on to say that it went under the other names of Tangeln, Chineseln, Prämeniren or Häfenbinden.[9] The rules for Mauscheln first appeared towards the end of the 19th century and was initially very popular in Jewish trading circles. In 1890, Ulmann described Angehen as "very popular in ladies' circles", noting that it was called Mauscheln in south Germany.[10] During the First World War it flourished among the German soldiers and has since become widespread in the German-speaking world.[11]

Mauscheln is one of the most popular games in Austria and is commonly played everywhere except in the states of Vorarlberg in the west and Burgenland in the east.[12] One modern source describes it as little more than an excerpt of Ombre and Boston and "so simple and mindless that anyone can learn it in five minutes." The game clearly revolves around money, resulting in attempts to classify and ban it as a game of chance. However, it is not a gambling game in the legal sense.

Basic rules

editPlayers and cards

editLike Tippen, Mauscheln may be played by 3 to 5 players with a 32-card, usually German-suited, pack. If more players participate a 52-card French pack may be used.[1][13]

Dealing

editThe dealer places a stake of four chips or coins (e.g. 40¢; it must be divisible by four) as the Pinke or Stamm in the pot and deals two cards to each player. The next one is turned as trumps and then another 2 cards are dealt. The remaining cards are placed face down on the table.[1]

Bidding

editForehand leads the bidding by announcing whether to "pass" (i.e. drop out of the current deal) or to "sneak" [a] (ich mauschele i.e. "I'll play"). In doing so, he undertakes to win at least two tricks. If he drops out, the other players in turn may opt to sneak. If no-one sneaks, the cards are thrown in, the next player pays 4 chips to the pot and deals for the next game. Once a player has declared "sneak", the others may either fold by saying "pass" (ich passe) or "not me!" (ich nicht!) or "play" (ich gehe mit, lit. "I'll go with you").[1][13]

If all the others fold, the sneaker (Mauschler) claims the pot without play. If at least one other player joins in, all active players, in order, may exchange up to 4 hand cards with the talon, throwing their discards face down onto a 'bonfire' (Scheiterhaufen).[14][13]

Playing

editThe sneaker leads to the first trick. Thereafter the winner of a trick leads to the next. Players must follow suit if possible or trump if unable to follow; subject to those rules, they must head the trick if they can.[14][13]

Scoring

editScoring is as follows: [14][13]

- For every trick taken a player wins 1/4 of the Pinke

- A player who 'joins in' but fails to take a trick pays a bête into the pot i.e. an amount equivalent to that in the pot; as does the sneaker if he or she only succeeds in taking one trick.

- A sneaker who remains trickless is Mauschelbete and pays a "sneaker bête" (double bête) into the pot.

Variations

editIn addition to variations in cutting and dealing, the following other variations are recorded:[14]

Knocking

editIf the dealer turns up a high trump such as the Sow (= Ace/Deuce), and before looking at his cards, he may 'knock' (klopfen) which in effect means he will become the sneaker. He takes over the game and has to take at least 2 tricks. If one or more of the others choose to play, the dealer looks at his cards, discards any he deems unfavourable and exchanges them with the trump turnup and fresh cards from the talon, without viewing them. Once the other active player(s) have exchanged, the dealer may pick up his new cards together with the 'knocked' trump.

Quartets

editIf anyone is dealt a quartet, they must discard them onto the bonfire, pay the Pinke and are then dealt another hand which they may exchange.

Belli

editThe ♦7 or 7 is the permanent, second-highest trump after the trump Ace or Sow. It may incur a penalty payment if lost to the Ace.[13]

Weli

editThe Weli ( 6) may be added to the pack as the 33rd card and permanent, second-highest trump

See also

editFootnotes

edit- ^ Parlett translates mauscheln as "diddle" which is its modern meaning, but "sneak" conveys its older sense, not least as a way of sneakily dodging the gambling ban on Dreiblatt by adding an extra card.

References

edit- ^ a b c d Grupp 1975–1979, p. 20.

- ^ Meyers Konversationslexikon: Mauscheln

- ^ Isabel Enzenbach: Mauscheln. In: Wolfgang Benz (ed.): Handbuch des Antisemitismus. Vol. 3: Begriffe, Ideologien, Theorien. De Gruyter Saur, Berlin 2008, ISBN 978-3-598-24074-4, p. 205 (retrieved via De Gruyter Online).

- ^ "Wortschatz Uni Leipzig". Archived from the original on 2013-12-03. Retrieved 2018-10-22.

- ^ a b Geiser 2004, pp. 58–61.

- ^ Although Kratzen is usually played with 'hop and jump' and the Weli, unlike Mauscheln.

- ^ Jungbauer, Dr. Gustav. Sudetendeutsche Zeitschrift für Volkskunde, Prague: J. G. Calve. p. 279.

- ^ Kastner & Folkvord 2005, p. 63.

- ^ _ (1832), pp. 370-371.

- ^ Ulmann 1890, p. 260/261.

- ^ Hülsemann 1930, p. 237.

- ^ Geiser 2004, p. 40.

- ^ a b c d e f Parlett 2008, p. 119.

- ^ a b c d Grupp 1975–1979, p. 21.

Literature

edit- _ (1832). Österreichische Zeitschrift für Rechts- und Staatswissenschaft. Vol. 3. Vienna: J.P. Sollinger.

- Althaus, Hans Peter (2002). Mauscheln: Ein Wort als Waffe. Berlin: de Gruyter.

- Geiser, Remigius (2004). "100 Kartenspiele des Landes Salzburg" (PDF). Talon (13). Archived from the original (PDF) on 27 August 2018.

- Grupp, Claus D. (1975–1979). Kartenspiele. Wiesbaden: Falken-Verlag Erich Sicker. ISBN 3-8068-2001-5.

- Grupp, Claus D. (1976). Glücksspiele mit Kugel, Würfel und Karten, Falken Verlag, Wiesbaden.

- Grupp, Claus D. (1996/97). Kartenspiele im Familien und Freundeskreis. Revised and redesigned edition. Original edition. Falken, Niedernhausen/Ts. ISBN 3-635-60061-X

- Hülsemann, Robert (1930). Das Buch der Spiele. Leipzig: Hesse & Becker.

- Kastner, Hugo; Folkvord, Gerald Kador (2005). Die große Humboldt-Enzyklopädie der Kartenspiele. Baden-Baden: Humboldt. ISBN 978-3-89994-058-9.

- Parlett, David (1992). The Oxford Dictionary of Card Games, Oxford University Press, Oxford.

- Parlett, David (2008). The Penguin book of card games. London: Penguin. ISBN 978-0-141-03787-5.

- Ulmann, S. (1890). Das Buch der Familienspiele. Vienna, Munich and Pest: A. Hartleben.