The Trasimene Line (so-named for Lake Trasimene, the site of a major battle of the Second Punic War in 217 BC) was a German defensive line during the Italian Campaign of World War II. It was sometimes known as the Albert Line. The German Commander-in-Chief (C-in-C), Generalfeldmarschall Albert Kesselring, used the line to delay the Allied northward advance in Italy in mid June 1944 to buy time to withdraw troops to the Gothic Line and finalise the preparation of its defenses.

Background

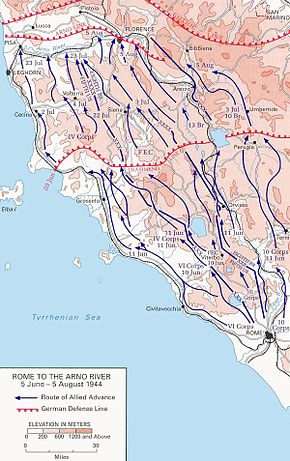

editAfter the Allied capture of the Italian capital of Rome on 4 June 1944 following the successful breakthrough at Monte Cassino and Anzio during Operation Diadem in May 1944, the German 14th and 10th Armies fell back: the 14th along the Tyrrhenian front and the 10th through central Italy and the Adriatic coast. The 10th escaped because General Mark W. Clark ordered Lucian Truscott to choose Operation Turtle towards Rome rather than Operation Buffalo as ordered by Sir Harold R. L. G. Alexander, which would have cut Route 6 at Valmonte. There was a huge gap between the armies and with the Allies advancing some 10 km per day, the flanks of both armies were exposed and encirclement was threatened.[1]

Two days after Rome fell, General Alexander, Commander-in-Chief (C-in-C) of the Allied Armies in Italy (AAI), received orders from his superior, General Sir Henry Maitland Wilson, the Allied Supreme Commander in the Mediterranean Theater of Operations (MTO), to push the retreating German Army 170 miles (270 km) north to a line running from Pisa to Rimini (i.e. the Gothic Line) as quickly as possible to prevent the establishment of any sort of coherent enemy defense in central Italy.

Battle

editOn Lieutenant General Mark W. Clark's U.S. Fifth Army front, the U.S. VI Corps, under Major General Lucian Truscott, was pushed up the coast along highway 1 and U.S. II Corps, under Major General Geoffrey Keyes, along highway 2 towards Viterbo. To their right the XIII Corps, under Lieutenant General Sidney Kirkman, part of the British Eighth Army under Lieutenant General Sir Oliver Leese, headed up highway 3 towards Terni and Perugia[2] whilst V Corps, under Lieutenant General Charles Walter Allfrey, advanced up the Adriatic coast.

Between 4 June and 16 June, whilst maintaining contact with the advancing Allies, Kesselring executed a remarkable and unorthodox maneuver with his depleted divisions, resulting in his two armies aligning and uniting their wings on the defensive positions on the Trasimene Line.[1] Remarkable though this was, he was probably helped by the confusion caused in the Allied advance by the relieving of the U.S. II and VI Corps (substituted by Major General Willis D. Crittenberger's U.S. IV Corps and Lieutenant General Alphonse Juin's French Expeditionary Corps). The British X Corps, under Lieutenant General Richard McCreery, had also been brought into the line on XIII Corps' right whilst V Corps had been relieved by the Polish II Corps, under Lieutenant General Władysław Anders.

By the last week of June the Allies were facing the Trasimene positions. Joachim Lemelsen's 14th Army had Frido von Senger und Etterlin's XIV Panzer Corps facing the U.S. IV Corps on the west coast and Alfred von Schlemm's 1st Parachute Corps facing the French Expeditionary Corps beside them. On 22 June, a U.S. armored attack near Massa Marittima was defeated by a German tank platoon under Oberfähnrich Oskar Röhrig from Heavy Tank Battalion 504. The German Tiger I's knocked out 11 Sherman tanks, while the terrified American tank crews abandoned another 12. The Germans suffered no losses. Röhrig was awarded the Knight's Cross of the Iron Cross for this action.[3] Four Shermans were knocked out by two Tigers from 508th Heavy Panzer Battalion on 12 July near Collesalvetti.[4]

Heinrich von Vietinghoff's 10th Army had Traugott Herr's LXXVI Panzer Corps facing XIII and X Corps and Valentin Feurstein's LI Mountain Corps facing the Polish II Corps on the Adriatic. The toughest defenses were around the lake itself with XIII Corps' British 78th Infantry Division experiencing fierce fighting on 17 June at Città della Pieve and 21 June at San Fatucchio. By 24 June they had worked their way round to the north shore and linked with X Corps' 4th and 10th Indian Infantry Divisions as the German defenders withdrew towards Arezzo.[5] On 8 July, the 2nd Company of the German 508th Heavy Panzer Battalion knocked out four British Shermans near Tavarnelle Val di Pesa southwest of Florence.[6]

The U.S. IV Corps also found progress slow but by 1 July had crossed the river Cecina and were within 20 miles (32 km) of Livorno. Meanwhile, the French Corps had been held up on the river Orcia west of Lake Trasimene until the parachutist defenders withdrew on 27 June allowing them to enter Siena on 3 July.[7]

Footnotes

edit- ^ a b Muhm, German Tactics in the Italian Campaign

- ^ Carver p. 209

- ^ Schneider 2004, p. 197.

- ^ Schneider 2004, p. 198.

- ^ Carver, pp. 216-217

- ^ Schneider 2004, p. 324.

- ^ Carver, p. 217

References

edit- Carver, Field Marshal Lord (2001). The Imperial War Museum Book of the War in Italy 1943-1945. London: Sidgwick & Jackson. ISBN 0-330-48230-0.

- Laurie, Clayton D. (3 October 2003) [1994]. Rome-Arno 1944. U.S. Army Campaigns of WWII. Washington: United States Army Center of Military History. ISBN 978-0-16-042085-6. CMH Pub 72-20. Archived from the original on 20 April 2011. Retrieved 2 July 2010.

- Muhm, Gerhard. "German Tactics in the Italian Campaign". Archived from the original on 2007-09-27. Retrieved 2007-08-02.

- Schneider, W. (2004). Tigers in Combat, Vol. 1. Stackpole. ISBN 978-0811731713.

External links

edit