Archiinocellia is an extinct genus of snakefly in the family Raphidiidae known from Eocene fossils found in western North America. The genus contains two species, the older Archiinocellia oligoneura and the younger Archiinocellia protomaculata. The type species is of Ypresian age and from the Horsefly Shales of British Columbia, while the younger species from the Lutetian Green River Formation in Colorado. Archiinocellia protomaculata was first described as Agulla protomaculata, and later moved to Archiinocellia.

| Archiinocellia Temporal range:

| |

|---|---|

| |

| Archiinocellia protomaculata holotype | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Arthropoda |

| Class: | Insecta |

| Order: | Raphidioptera |

| Family: | Raphidiidae |

| Genus: | †Archiinocellia Handlirsch, 1910 |

| Species | |

| |

| Synonyms | |

| |

Distribution

editArchiinocellia oligoneura is known from a single specimen collected by Canadian geologist and paleontologist Lawrence M. Lambe during fieldwork in central British Columbia. The fossil was collected on July 21, 1906, from fossil bearing rocks near the Horsefly mine in Horsefly, British Columbia.[1][2]

The Archiinocellia protomaculata fossils were recovered from the Green River Formations Parachute Member which outcrops in the Piceance Creek Basin and Uinta Basin of Garfield County, northwestern Colorado.[3]

Age

editThe age of the Horsefly sites was considered Oligocene for many years and Archiinocellia is still listed as an Oligocene genus in many modern works.[4] However, the site has been re-dated to the Early Eocene and is part of the Okanagan Highlands fossil localities, which stretch from Driftwood Canyon Provincial Park in Smithers, B.C. south to Republic, Washington.[5]

The Parachute Member of the Green River Formation is younger than the Horsefly Beds, with a Middle Eocene age, placing it in the Lutetian stage.[3]

History and Classification

editThe A. oligoneura holotype specimen was first studied and described by the prolific paleoentomologist Anton Handlirsch (1910). The genus was named from archi referring to the primitive appearance of the wing characters and Inocellia, the type genus for Inocelliidae, the family the genus was placed in originally. The species name is a combination of oligo in reference to Oligocene, the age the location of the fossil was thought to be, and "neura".

After examining the holotype, Frank Carpenter (1936) noted that the fossil was poorly preserved and the placement of the wings presented difficulties.[6] While accepting Handlirschs drawings of the wings, Carpenter states the damage to the wings prevents any determination of genus placement lower than Raphidioptera incertae sedis.[6] This placement was followed by Michael Engel (2002) in his listing of Raphidioptera fossil genera, where he placed the genus no lower than the suborder Raphidiomorpha.[4] Engel also noted the genus to be the only snakefly fossil genus from British Columbia and one of only two from Canada at that time.[4]

Archiinocellia protomaculata is known from a series of eighteen fossils, the holotype, three paratype females, ten male paratypes, and three paratypes of indeterminate sex. The holotype, number "USNM 31487", is a single female specimen consisting of part and counterpart fossils. The type series plus an additional male specimen tentatively identified as also A. protomaculata are preserved in the Department of Paleobiology collections for the Smithsonians National Museum of Natural History. A. protomaculata was first studied by Michael S. Engel with his 2009 type description being published in the journal Transactions of the Kansas Academy of Science.[3] Engel coined the specific epithet protomaculata as a combination of the Latin word "protos" meaning "first" and "macula" meaning "mark".[3] At least one other specimen is known and was figured in a 1995 publication by Dayvault et al, but that specimen is thought to still be in the private collection of William Hawes. At the time of the species description, A. protomaculata was the only member of the order Raphidioptera to be described from the Green River Formation.[3]

The Horsefly Beds and Green river Formation fossils were reexamined and redescribed by Archibald and Makarkin (2021), who identified A. protomaculata as a member of Archiinocellia rather than of Agulla. They also refined the genus placement, moving it from Raphidiodea incertae sedis to a member of Raphidiidae.[2]

Description

editArchiinocellia oligoneura

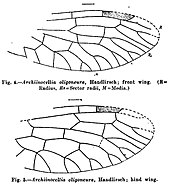

editThe holotype consists of a superimposed partial pair of wings, one forewing and one hindwing, thus not allowing for gender identification and body description. The bases and several small areas of the apex and pterostigmal region are missing.[1] The preserved length of 7 millimetres (0.28 in) allows the estimation of a total forewing length between 12 millimetres (0.47 in) and 14 millimetres (0.55 in).[1] Though difficult to distinguish from one another, the forewing and hindwing vein structures show several distinct traits that set the genus apart from other raphidiopteran genera. Anton Handlirsch notes the damage to the pterostigma prevents determining if any cross veining is present.[1] In a basal position from the stigma is a cross vein which does not correspond to the cross vein in the same region of modern Raphidia species.[1]

Archiinocellia protomaculata

editSpecimens of A. protomaculata average 8.33 millimetres (0.328 in) in length not including the ovipositor in the females.[3] Overall the species was a dark brown to brown coloration, with the legs shading from light brown to a yellow tone. The head is dark brown with extensive yellow coloration including yellow stripes along the sides and to the rear of the eyes, and a central stripe of yellow running down the center of the head behind the eyes.[3] In females the gentility curved ovipositor is light brown and ranges between 3.47 and 3.8 millimetres (0.137 and 0.150 in) in length. The wings are hyaline in coloration with a slight darkening of the pterostigma and averaging 7.42 millimetres (0.292 in) long for the fore-wings. The vein structure of the fore-wing and notably the length and placement of the M vein in the hind-wing indicated at the time, the species to be a member of the genus Agulla.[3]

References

edit- ^ a b c d e Handlirsch, A. (1910). "Canadian fossil insects". Contributions to Canadian Paleontology. 2 (3): 187–193.

- ^ a b Archibald, S. B.; Makarkin, V. N. (2021). "Early Eocene snakeflies (Raphidioptera) of western North America from the Okanagan Highlands and Green River Formation". Zootaxa. 4951 (1): 41–79. doi:10.11646/zootaxa.4951.1.2. PMID 33903413. S2CID 233411745.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Engel, Michael S. (2011). "A new snakefly from the Eocene Green River Formation (Raphidioptera: Raphidiidae)". Transactions of the Kansas Academy of Science. 114 (1–2): 77–87. doi:10.1660/062.114.0107. S2CID 85011364.

- ^ a b c Engel, M.S. (2002). "The Smallest Snakefly(Raphidioptera: Mesoraphidiidae): A New Species in Cretaceous Amber from Myanmar, with a Catalog of Fossil Snakeflies" (PDF). American Museum Novitates (3363): 1–22. doi:10.1206/0003-0082(2002)363<0001:TSSRMA>2.0.CO;2. hdl:2246/2852. S2CID 83616111.

- ^ Archibald, S.B.; Makarkin V.N. (2006). "Tertiary Giant Lacewings (Neuroptera: Polystechotidae): Revision and Description of New Taxa From Western North America and Denmark". Journal of Systematic Palaeontology. 4 (2): 119–155. doi:10.1017/S1477201906001817. S2CID 55970660.

- ^ a b Carpenter, F.M. (1936). "Revision of the Nearctic Raphidiodea (Recent and Fossil)". Proceedings of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences. 89 (2): 89–158. doi:10.2307/20023217. JSTOR 20023217.