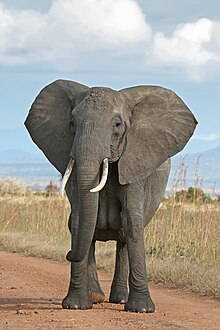

The African bush elephant (Loxodonta africana), also known as the African savanna elephant, is one of two extant African elephant species and one of three extant elephant species. It is the largest living terrestrial animal, with bulls reaching an average shoulder height of 3.04–3.36 metres (10.0–11.0 ft) and a body mass of 5.2–6.9 tonnes (11,500–15,200 lb), with the largest recorded specimen having a shoulder height of 3.96 metres (13.0 ft) and an estimated body mass of 10.4 tonnes (22,900 lb).[3]

| African bush elephant Temporal range:

| |

|---|---|

| |

| A female in Mikumi National Park, Tanzania | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | Proboscidea |

| Family: | Elephantidae |

| Genus: | Loxodonta |

| Species: | L. africana[1]

|

| Binomial name | |

| Loxodonta africana[1] (Blumenbach, 1797)

| |

| Subspecies | |

|

See text | |

| |

| Range of the African bush elephant Resident Possibly resident Possibly extinct Resident and reintroduced

| |

| Synonyms | |

|

Elephas africanus | |

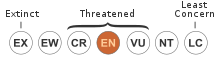

It is distributed across 37 African countries and inhabits forests, grasslands and woodlands, wetlands and agricultural land. Since 2021, it has been listed as Endangered on the IUCN Red List. It is threatened foremost by habitat destruction, and in parts of its range also by poaching for meat and ivory.[2]

It is a social mammal, travelling in herds composed of cows and their offspring. Adult bulls usually live alone or in small bachelor groups. It is a herbivore, feeding on grasses, creepers, herbs, leaves, and bark. The menstrual cycle lasts three to four months, and females are pregnant for 22 months, the longest gestation period of any mammal.[4]

Taxonomy and evolution

editIn the 19th and 20th centuries, several zoological specimens were described by naturalists and curators of natural history museums from various parts of Africa, including:

- Elephas (Loxodonta) oxyotis and Elephas (Loxodonta) knochenhaueri by Paul Matschie in 1900. The first was a specimen from the upper Atbara River in northern Ethiopia, and the second a specimen from the Kilwa area in Tanzania.[5]

- Elephas africanus toxotis, selousi, peeli, cavendishi, orleansi and rothschildi by Richard Lydekker in 1907 who assumed that ear size is a distinguishing character for a race. These specimens were shot in South Africa, Mashonaland in Zimbabwe, Aberdare Mountains and Lake Turkana area in Kenya, Somaliland, and western Sudan, respectively.[6]

- North African elephant (L. a. pharaohensis) by Paulus Edward Pieris Deraniyagala in 1948 was a specimen from Fayum in Egypt.[7]

Today, these names are all considered synonyms.[1]

A genetic study based on mitogenomic analysis revealed that the African and Asian elephant genetically diverged about 7.6 million years ago.[8] Phylogenetic analysis of nuclear DNA of African bush and forest elephants, Asian elephant, woolly mammoth, and American mastodon revealed that the African bush elephant and the African forest elephant form a sister group that genetically diverged at least 1.9 million years ago. They are therefore considered distinct species. Gene flow between the two species, however, might have occurred after the split.[9] Some authors have suggested that L. africana evolved from Loxodonta atlantica.[10]

The fossil record for L. africana is sparse. The earliest possible records of the species are from the Shungura Formation around Omo in Ethiopia, which are dated to the Early Pleistocene, around 2.44-2.27 million years ago.[11] Another possible early record is from the Kanjera site in Kenya, dating to the Middle Pleistocene, around 500,000 years ago.[12][13] Genetic analysis suggests a major population expansion between 500,000 and 100,000 years ago.[13] Records become more common during the Late Pleistocene, following the extinction of the last African Palaeoloxodon species, Palaeoloxodon jolensis.[13]

Description

editThe African bush elephant has grey skin with scanty hairs. Its large ears cover the whole shoulder,[14] and can grow as large as 2 m × 1.5 m (6 ft 7 in × 4 ft 11 in).[15] Its large ears help to reduce body heat; flapping them creates air currents and exposes large blood vessels on the inner sides to increase heat loss during hot weather.[16] The African bush elephant's ears are pointed and triangular shaped. Its occipital plane slopes forward. Its back is shaped markedly concave. Its sturdy tusks are curved out and point forward.[17] Its long trunk or proboscis ends with two finger-like tips.[18]

Size

editThe African bush elephant is the largest and heaviest living land animal. On average, mature fully grown males are about 3.20 m (10.5 ft) tall at the shoulder and weigh 6.0 t (6.6 short tons) (with 90% of fully grown males being between 3.04–3.36 m (10.0–11.0 ft) and 5.2–6.9 t (5.7–7.6 short tons)) while mature fully grown females are smaller at about 2.60 m (8 ft 6 in) tall at the shoulder and 3.0 t (3.3 short tons) in weight on average (with 90% of fully grown females ranging between 2.47–2.73 m (8 ft 1 in – 8 ft 11 in) and 2.6–3.5 t (2.9–3.9 short tons)).[3][19][20][21] The maximum recorded shoulder height of an adult bull is 3.96 m (13.0 ft), with this individual having an estimated weight of 10.4 t (11.5 short tons).[3] Elephants attain their maximum stature when they complete the fusion of long-bone epiphyses, occurring in males around the age of 40 and females around 25 years of age.[3]

Dentition

editThe dental formula of the African bush elephant is 1.0.3.30.0.3.3 × 2 = 26. They develop six molars in each jaw quadrant that erupt at different ages and differ in size.[22] The first molars grow to a size of 2 cm (0.79 in) wide by 4 cm (1.6 in) long, are worn by the age of one year and lost by the age of about 2.5 years. The second molars start protruding at the age of about six months, and grow to a size of 4 cm (1.6 in) wide by 7 cm (2.8 in) long and are lost by the age of 6–7 years. The third molars protrude at the age of about one year, grow to a size of 5.2 cm (2.0 in) wide by 14 cm (5.5 in) long, and are lost by the age of 8–10 years. The fourth molars show by the age of 6–7 years, grow to a size of 6.8 cm (2.7 in) wide by 17.5 cm (6.9 in) long and are lost by the age of 22–23 years. The dental alveoli of the fifth molars are visible by the age of 10–11 years. They grow to a size of 8.5 cm (3.3 in) wide by 22 cm (8.7 in) long and are worn by the age of 45–48 years. The dental alveoli of the last molars are visible by the age of 26–28 years. They grow to a size of 9.4 cm (3.7 in) wide by 31 cm (12 in) long and are well worn by the age of 65 years.[23]

Both sexes have tusks, which erupt when they are 1–3 years old and grow throughout life.[22] Tusks grow from deciduous teeth known as tushes that develop in the upper jaw and consist of a crown, root and pulpal cavity, which are completely formed soon after birth. Tushes reach a length of 5 cm (2.0 in).[24] They are composed of dentin and coated with a thin layer of cementum. Their tips bear a conical layer of enamel that is usually worn off when the elephant is five years old.[25] Tusks of bulls grow faster than tusks of cows. Mean weight of tusks at the age of 60 years is 109 kg (240 lb) in bulls and 17.7 kg (39 lb) in cows.[22] The longest known tusk of an African bush elephant measured 3.51 m (11.5 ft) and weighed 117 kg (258 lb).[26]

Distribution and habitat

editThe African bush elephant occurs in sub-Saharan Africa which includes Uganda, Kenya, Tanzania, Botswana, Zimbabwe, Namibia, Zambia, Angola, Malawi, Mali, Rwanda, Mozambique and South Africa. It moves between a variety of habitats, including subtropical and temperate forests, dry and seasonally flooded grasslands, woodlands, wetlands, and agricultural land from sea level to mountain slopes. In Mali and Namibia, it also inhabits desert and semi-desert areas.[2]

In Ethiopia, the African bush elephant has historically been recorded up to an elevation of 2,500 m (8,200 ft). By the late 1970s, the population had declined to a herd in the Dawa River valley and one close to the Kenyan border.[27]

Behavior and ecology

editSocial behavior

editThe core of elephant society is the family unit, which mostly comprises several adult cows, their daughters, and their prepubertal sons. Iain Douglas-Hamilton, who observed African bush elephants for 4.5 years in Lake Manyara National Park, coined the term 'kinship group' for two or more family units that have close ties. The family unit is led by a matriarch who at times also leads the kinship group.[28][29] Groups cooperate in locating food and water, in self-defense, and in caring for offspring (termed allomothering).[28] Group size varies seasonally and between locations. In Tsavo East and Tsavo West National Parks, groups are bigger in the rainy season and areas with open vegetation.[30] Aerial surveys in the late 1960s to early 1970s revealed an average group size of 6.3 individuals in Uganda's Rwenzori National Park and 28.8 individuals in Chambura Game Reserve. In both sites, elephants aggregated during the wet season, whereas groups were smaller in the dry season.[31]

Young bulls gradually separate from the family unit when they are between 10 and 19 years old. They range alone for some time or form all-male groups.[32] A 2020 study highlighted the importance of old bulls for the navigation and survival of herds and raised concerns over the removal of old bulls as "currently occur[ring] in both legal trophy hunting and illegal poaching".[33]

Temperature regulation

editThe African bush elephant has curved skin with bending cracks, which support thermoregulation by retaining water.[34] These bending cracks contribute to an evaporative cooling process which helps to maintain body temperature via homeothermy regardless of air temperature.[35]

Diet

editThe African bush elephant is herbivorous. It is a mixed feeder, consuming both grasses, as well as woody vegetation (browse), with the proportions varying wildly depending on the habitat and time of year, ranging from almost exclusively grazing to near-total browsing.[36] African bush elephants consumption of woody plants, particularly their habit of uprooting trees, has the ability to alter the local environment, transforming woodlands into grasslands.[37] African bush elephants also at times consume fruit and serve as seed dispersers.[38] Adults can consume up to 150 kg (330 lb) of food per day.[39] To supplement their diet with minerals, they congregate at mineral-rich water holes, termite mounds, and mineral licks.[40] Salt licks visited by elephants in the Kalahari contain high concentrations of water-soluble sodium.[41] Elephants drink 180–230 litres (50–60 US gal) of water daily, and seem to prefer sites where water and soil contain sodium. In Kruger National Park and on the shore of Lake Kariba, elephants were observed to ingest wood ash, which also contains sodium.[42]

Communication

editAfrica bush elephants use their trunks for tactile communication. When greeting, a lower ranking individual will insert the tip of its trunk into its superior's mouth. Elephants will also stretch out their trunk toward an approaching individual they intend to greet. Mother elephants reassure their young with touches, embraces, and rubbings with the foot while slapping disciplines them. During courtship, a couple will caress and intertwine with their trunks while playing and fighting individuals wrestle with them.[43]

Elephant vocals are variations of rumbles, trumpets, squeals, and screams. Rumbles are mainly produced for long-distance communication and cover a broad range of frequencies which are mostly below what a human can hear. Infrasonic rumbles can travel vast distances and are important for attracting mates and scaring off rivals.[43]

At Amboseli National Park several different infrasonic calls have been identified:[44]

- Greeting rumble – is emitted by adult female members of a family group that have united after having been separated for several hours.

- Contact call – soft, unmodulated sounds made by an individual that has been separated from the group.

- Contact answer – made in response to the contact call; starts out loud, but softens toward the end.

- "Let's go" rumble – a soft rumble emitted by the matriarch to signal to the other herd members that it is time to move to another spot.

- Musth rumble – distinctive, low-frequency pulsated rumble emitted by musth males (nicknamed the "motorcycle").

- Female chorus – a low-frequency, modulated chorus produced by several cows in response to a musth rumble.

- Postcopulatory call – made by an oestrous cow after mating.

- Mating pandemonium – calls of excitement made by a cow's family after she has mated.

Growls are audible rumbles and happen during greetings. When in pain or fear, an elephant makes an open-mouthed growl known as a bellow while a drawn-out growl is a moan. Growling can escalate into a roaring when the elephant is issuing a threat. Trumpeting is made by blowing through the trunk and signals excitement, distress, or aggression. Juvenile elephants squeal in distress while screaming is made by adults for intimidation.[43]

Musth

editBulls in musth experience swelling of the temporal glands and secretion of fluid, the musth fluid, which flows down their cheeks. They begin to dribble urine, initially as discrete drops and later in a regular stream. These manifestations of musth last from a few days to months, depending on the age and condition of the bull. When a bull has been urinating for a long time, the proximal part of the penis and the distal end of the sheath show a greenish coloration, termed the 'green penis syndrome' by Joyce Poole and Cynthia Moss.[45] Males in musth become more aggressive. They guard and mate with females in estrus, who stay closer to bulls in musth than to non-musth bulls.[46] Urinary testosterone increases during musth.[47] Bulls begin to experience musth by the age of 24 years. Periods of musth are short and sporadic in young bulls up to 35 years old, lasting a few days to weeks. Older bulls are in musth for 2–5 months every year. Musth occurs mainly during and following the rainy season when females are in estrus.[48] Bulls in musth often chase each other and are aggressive towards other bulls in musth. When old and high-ranking bulls in musth threaten and chase young musth bulls, either the latter leave the group or their musth ceases.[49]

Young bulls in musth killed about 50 white rhinoceros in Pilanesberg National Park between 1992 and 1997. This unusual behavior was attributed to their young age and inadequate socialisation; they were 17–25-year-old orphans from culled families that grew up without the guidance of dominant bulls. When six adult bulls were introduced into the park, the young bulls did not attack rhinos anymore, indicating older bulls suppress the musth and aggressiveness of younger bulls.[50][51] Similar incidents were recorded in Hluhluwe-Umfolozi Park, where young bulls killed five black and 58 white rhinoceros between 1991 and 2001. After the introduction of ten bulls, each up to 45 years old, the number of rhinos killed by elephants decreased considerably.[52]

Reproduction

editSpermatogenesis starts when bulls are about 15 years old.[53] However, males have not begun sexual cycles, not experiencing their first musth period until they are 25 or 30 years of age.[54] Cows ovulate for the first time at the age of 11 years.[55] They are in estrus for 2–6 days.[56] In captivity, cows have an oestrous cycle lasting 14–15 weeks. Foetal gonads enlarge during the second half of pregnancy.[57]

African bush elephants mate during the rainy season.[55] Bulls in musth cover long distances in search of cows and associate with large family units. They listen for the cows' loud, very low frequency calls and attract cows by calling and by leaving trails of strong-smelling urine. Cows search for bulls in musth, listen for their calls, and follow their urine trails.[58] Bulls in musth are more successful at obtaining mating opportunities than those who are not. A cow may move away from bulls that attempt to test her estrous condition. If pursued by several bulls, she will run away. Once she chooses a mating partner, she will stay away from other bulls, which are threatened and chased away by the favoured bull. Competition between bulls overrides their choice sometimes.[56]

Gestation lasts 22 months. The interval between births was estimated at 3.9 to 4.7 years in Hwange National Park.[55] Where hunting pressure on adult elephants was high in the 1970s, cows gave birth once in 2.9 to 3.8 years.[59] Cows in Amboseli National Park gave birth once in 5 years on average.[56]

The birth of a calf was observed in Tsavo East National Park in October 1990. A group of 80 elephants including eight bulls had gathered in the morning in a 150 m (490 ft) radius around the birth site. A small group of calves and cows stood near the pregnant cow, rumbling and flapping their ears. One cow seemed to assist her. While she was in labour, fluid streamed from her temporal and ear canals. She remained standing while giving birth. The newborn calf struggled to its feet within 30 minutes and walked 20 minutes later. The mother expelled the placenta about 100 minutes after birth and covered it with soil immediately.[60]

Captive-born calves weigh between 100 and 120 kg (220 and 260 lb) at birth and gain about 0.5 kg (1.1 lb) weight per day.[61] Cows lactate for about 4.8 years.[62] Calves exclusively suckle their mother's milk during the first three months. Thereafter, they start feeding independently and slowly increase the time spent feeding until they are two years old. During the first three years, male calves spend more time suckling and grow faster than female calves. After this period, cows reject male calves more frequently from nursing than female calves.[63]

The maximum lifespan of the African bush elephant is between 70 and 75 years.[64] Its generation length is 25 years.[65]

Predators

editAdult elephants are considered invulnerable to predation.[66] Calves, usually under two years, are sometimes preyed on by lions and spotted hyenas.[18] Adult elephants often chase off predators, especially lions, by mobbing behavior.[67] Juveniles are usually well defended by protective adults though serious drought makes them vulnerable to lion predation.[68]

In Botswana's Chobe National Park, lions attacked and fed on juvenile and subadult elephants during the drought when smaller prey species were scarce. Between 1993 and 1996, lions successfully attacked 74 elephants; 26 were older than nine, and one was a bull of over 15 years. Most were killed at night, and hunts occurred more often during waning moon nights than during bright moon nights.[69] In the same park, lions killed eight elephants in October 2005 that were aged between 1 and 11 years, two of them older than 8 years. Successful hunts took place after dark when prides exceeded 27 lions and herds were smaller than 5 elephants.[70]

Threats

editThe African bush elephant is threatened primarily by habitat loss and fragmentation following conversion of natural habitat for livestock farming, plantations of non-timber crops, and building of urban and industrial areas. As a result, the human-elephant conflict has increased.[2]

Poaching

editPoachers target foremost elephant bulls for their tusks, which leads to a skewed sex ratio and affects the survival chances of a population. Access of poachers to unregulated black markets is facilitated by corruption and periods of civil war in some elephant range countries.[71]

During the 20th century, the African bush elephant population was decimated.[72] Poaching of the elephant has dated back to the years 1970 and 1980, which were considered the largest killings in history. The species is placed in harm's way due to the limited conservation areas provided in Africa. In most cases, the killings of the African bush elephant have occurred near the outskirts of the protected areas.[2]

Between 2003 and 2015, the illegal killing of 14,606 African bush elephants was reported by rangers across 29 range countries. Chad is a major transit country for smuggling of ivory in West Africa. This trend was curtailed by raising penalties for poaching and improving law enforcement.[73]

In June 2002, a container packed with more than 6.5 t (6.4 long tons; 7.2 short tons) ivory was confiscated in Singapore. It contained 42,120 hanko stamps and 532 tusks of African bush elephants that originated in Southern Africa, centered in Zambia and neighboring countries. Between 2005 and 2006, a total of 23.461 t (23.090 long tons; 25.861 short tons) ivory plus 91 unweighed tusks of African bush elephants were confiscated in 12 major consignments being shipped to Asia.[74]

When the international ivory trade reopened in 2006, the demand and price for ivory increased in Asia. The African bush elephant population in Chad's Zakouma National Park numbered 3,900 individuals in 2005. Within five years, more than 3,200 elephants were killed. The park did not have sufficient guards to combat poaching, and their weapons were outdated. Well-organized networks facilitated smuggling the ivory through Sudan.[75] Poaching also increased in Kenya in those years.[76] In Samburu National Reserve, 41 bulls were illegally killed between 2008 and 2012, equivalent to 31% of the reserve's elephant population.[77]

These killings were linked to confiscations of ivory and increased prices for ivory on the local black market.[78] About 10,370 tusks were confiscated in Singapore, Hong Kong, Taiwan, Philippines, Thailand, Malaysia, Kenya and Uganda between 2007 and 2013. Genetic analysis of tusk samples showed that they originated from African bush elephants killed in Tanzania, Mozambique, Zambia, Kenya, and Uganda. Most of the ivory was smuggled through East African countries.[79]

In addition to elephants being poached, their carcasses may be poisoned by the poachers to avoid detection by vultures, which help rangers detect poaching activity by circling dead animals. This poses a threat to those vultures or birds that scavenge the carcasses. On 20 June 2019, the carcasses of two tawny eagles and 537 endangered Old World vultures including 468 white-backed vultures, 17 white-headed vultures, 28 hooded vultures, 14 lappet-faced vultures and 10 Cape vultures found dead in northern Botswana were suspected to have died after eating the poisoned carcasses of three elephants.[80][81][82][83]

Intensive poaching leads to strong selection on tusk attributes; African elephants in areas with heavy poaching often have smaller tusks and a higher frequency of congenitally tuskless females, whereas congenital tusklessness is rarely if ever observed in males.[84] A study in Mozambique's Gorongosa National Park revealed that poaching during the Mozambican Civil War led to the increasing birth of tuskless females when the population recovered.[85]

Habitat changes

editVast areas in Sub-Saharan Africa were transformed for agricultural use and the building of infrastructure. This disturbance leaves the elephants without a stable habitat and limits their ability to roam freely. Large corporations associated with commercial logging and mining have fragmented the land, giving poachers easy access to the African bush elephant.[86] As human development grows, the human population faces the trouble of contact with the elephants more frequently, due to the species need for food and water. Farmers residing in nearby areas come into conflict with the African bush elephants rummaging through their crops. In many cases, they kill the elephants as soon as they disturb a village or forage upon its crops.[72] Deaths caused by browsing on rubber vine, an invasive alien plant, have also been reported.[87]

Pathogens

editObservations at Etosha National Park indicate that African bush elephants die due to anthrax foremost in November at the end of the dry season.[88] Anthrax spores spread through the intestinal tracts of vultures, jackals and hyaenas that feed on the carcasses. Anthrax killed over 100 elephants in Botswana in 2019.[89]

It is thought that wild bush elephants can contract fatal tuberculosis from humans.[90] Infection of the vital organs by Citrobacter freundii bacteria caused the death of an otherwise healthy bush elephant after capture and translocation.[87]

From April to June 2020, over 400 bush elephants died in Botswana's Okavango Delta region after drinking from desiccating waterholes that were infested with cyanobacteria.[91] Neurotoxins produced by the cyanobacteria caused calves and adult elephants to wander around confused, emaciated and in distress. The elephants collapsed when the toxin impaired their motor functions and their legs became paralysed. Poaching, intentional poisoning, and anthrax were excluded as potential causes.[92]

Conservation

editBoth African elephant species have been listed on Appendix I of the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora since 1989. In 1997, populations of Botswana, Namibia, and Zimbabwe were placed on CITES Appendix II, as were populations of South Africa in 2000. Community-based conservation programmes have been initiated in several range countries, which contributed to reducing human-elephant conflict and increasing local people's tolerance towards elephants.[2]

In 1986, the African Elephant Database was initiated to collate and update information on the distribution and status of elephant populations in Africa. The database includes results from aerial surveys, dung counts, interviews with local people, and data on poaching.[73]

Researchers discovered that playing back the recorded sounds of African bees is an effective method to drive elephants away from settlements.[93]

Status

editIn 2008, the IUCN Red List assessed the African elephant (then considered as a single species) as vulnerable. Since 2021, the African bush elephant has individually been assessed Endangered, after the global population was found to have decreased by more than 50% over 3 generations.[94] About 70% of its range is located outside protected areas.[2]

In 2016, the global population was estimated at 415,428 ± 20,111 individuals distributed in a total area of 20,731,202 km2 (8,004,362 sq mi), of which 30% is protected. Approximately 42% of the total population lives in nine southern African countries comprising 293,447 ± 16,682 individuals; Africa's largest population lives in Botswana with 131,626 ± 12,508 individuals.[73]

In captivity

editThe social behavior of elephants in captivity mimics that of those in the wild. Cows are kept with other cows, in groups, while bulls tend to be separated from their mothers at a young age and are kept apart. According to Schulte, in the 1990s, in North America, a few facilities allowed bull interaction. Elsewhere, bulls were only allowed to smell each other. Bulls and cows were allowed to interact for specific purposes such as breeding. In that event, cows were more often moved to the bull than the bull to the cow. Cows are more often kept in captivity because they are easier and less expensive to house.[95]

See also

editNotes

edit- ^ The populations of Botswana, Namibia, South Africa, and Zimbabwe are listed in Appendix II for specific purposes.

References

edit- ^ a b Shoshani, J. (2005). "Order Proboscidea". In Wilson, D.E.; Reeder, D.M (eds.). Mammal Species of the World: A Taxonomic and Geographic Reference (3rd ed.). Johns Hopkins University Press. p. 91. ISBN 978-0-8018-8221-0. OCLC 62265494.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Gobush, K.S.; Edwards, C.T.T.; Balfour, D.; Wittemyer, G.; Maisels, F.; Taylor, R.D. (2022) [amended version of 2021 assessment]. "Loxodonta africana". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2022: e.T181008073A223031019. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2022-2.RLTS.T181008073A223031019.en.

- ^ a b c d Larramendi, A. (2016). "Shoulder height, body mass and shape of proboscideans" (PDF). Acta Palaeontologica Polonica. 61 (3): 537–574. doi:10.4202/app.00136.2014. S2CID 2092950. Archived (PDF) from the original on 24 August 2016. Retrieved 30 August 2016.

- ^ Foley, C. A. H.; Papageorge, S.; Wasser, S. K. (3 August 2001). "Noninvasive Stress and Reproductive Measures of Social and Ecological Pressures in Free-Ranging African Elephants". Conservation Biology. 15 (4): 1134–1142. Bibcode:2001ConBi..15.1134F. doi:10.1046/j.1523-1739.2001.0150041134.x. ISSN 0888-8892. S2CID 84294169.

- ^ Matschie, P. (1900). "Geographische Abarten des Afrikanischen Elefanten". Sitzungsberichte der Gesellschaft Naturforschender Freunde zu Berlin. 3: 189–197.

- ^ Lydekker, R. (1907). "The Ears as a Race-Character in the African Elephant". Proceedings of the Zoological Society of London (January to April): 380–403. doi:10.1111/j.1096-3642.1907.tb01824.x.

- ^ Deraniyagala, P. E. P. (1955). Some extinct elephants, their relatives, and the two living species. Colombo: Ceylon National Museums Publication.

- ^ Rohland, N.; Malaspinas, A. S.; Pollack, J. L.; Slatkin, M.; Matheus, P. & Hofreiter, M. (2007). "Proboscidean mitogenomics: chronology and mode of elephant evolution using mastodon as outgroup". PLOS Biology. 5 (8): e207. doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.0050207. PMC 1925134. PMID 17676977.

- ^ Rohland, N.; Reich, D.; Mallick, S.; Meyer, M.; Green, R. E.; Georgiadis, N. J.; Roca, A. L. & Hofreiter, M. (2010). "Genomic DNA Sequences from Mastodon and Woolly Mammoth Reveal Deep Speciation of Forest and Savanna Elephants". PLOS Biology. 8 (12): e1000564. doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.1000564. PMC 3006346. PMID 21203580.

- ^ Todd, Nancy E. (2010). "New Phylogenetic Analysis of the Family Elephantidae Based on Cranial-Dental Morphology". The Anatomical Record: Advances in Integrative Anatomy and Evolutionary Biology. 293 (1): 74–90. doi:10.1002/ar.21010. PMID 19937636.

- ^ Sanders, William J. (7 July 2023). Evolution and Fossil Record of African Proboscidea (1 ed.). Boca Raton: CRC Press. pp. 257–261. doi:10.1201/b20016. ISBN 978-1-315-11891-8.

- ^ Stewart, Mathew; Louys, Julien; Price, Gilbert J.; Drake, Nick A.; Groucutt, Huw S.; Petraglia, Michael D. (May 2019). "Middle and Late Pleistocene mammal fossils of Arabia and surrounding regions: Implications for biogeography and hominin dispersals". Quaternary International. 515: 12–29. Bibcode:2019QuInt.515...12S. doi:10.1016/j.quaint.2017.11.052. S2CID 134460011.

- ^ a b c Manthi, Fredrick Kyalo; Sanders, William J.; Plavcan, J. Michael; Cerling, Thure E.; Brown, Francis H. (September 2020). "Late Middle Pleistocene Elephants from Natodomeri, Kenya and the Disappearance of Elephas (Proboscidea, Mammalia) in Africa". Journal of Mammalian Evolution. 27 (3): 483–495. doi:10.1007/s10914-019-09474-9. ISSN 1064-7554. S2CID 198190671.

- ^ Jardine, W. (1836). "The Elephant of Africa". The Naturalist's Library. Vol. V. Natural History of the Pachydermes, Or, Thick-skinned Quadrupeds. Edinburgh, London, Dublin: W.H. Lizars, Samuel Highley, W. Curry, jun. & Company. pp. 124–132.

- ^ Estes, R. D. (1999). "Elephant Loxodonta africana Family Elephantidae, Order Proboscidea". The Safari Companion: A Guide to Watching African Mammals Including Hoofed Mammals, Carnivores, and Primates (Revised and expanded ed.). Vermont: Chelsea Green Publishing Company. pp. 223–233. ISBN 1-890132-44-6.

- ^ Shoshani, J. (1978). "General information on elephants with emphasis on tusks". Elephant. 1 (2): 20–31. doi:10.22237/elephant/1491234053. Archived from the original on 20 February 2020. Retrieved 11 June 2019.

- ^ Grubb, P.; Groves, C. P.; Dudley, J. P.; Shoshani, J. (2000). "Living African elephants belong to two species: Loxodonta africana (Blumenbach, 1797) and Loxodonta cyclotis (Matschie, 1900)". Elephant. 2 (4): 1–4. doi:10.22237/elephant/1521732169.

- ^ a b Laursen, L. & Bekoff, M. (1978). "Loxodonta africana" (PDF). Mammalian Species (92): 1–8. doi:10.2307/3503889. JSTOR 3503889. S2CID 253949585. Archived from the original (PDF) on 30 April 2013.

- ^ Laws, R. M. & Parker, I. S. C. (1968). "Recent studies on elephant populations in East Africa". Symposia of the Zoological Society of London. 21: 319–359.

- ^ Hanks, J. (1972). "Growth of the African elephant (Loxodonta africana)". East African Wildlife Journal. 10 (4): 251–272. Bibcode:1972AfJEc..10..251H. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2028.1972.tb00870.x.

- ^ Laws, R. M.; Parker, I. S. C.; Johnstone, R. C. B. (1975). Elephants and Their Habitats: The Ecology of Elephants in North Bunyoro, Uganda. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

- ^ a b c Laws, R. M. (1966). "Age criteria for the African elephant: Loxodonta a. africana". African Journal of Ecology. 4 (1): 1–37. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2028.1966.tb00878.x.

- ^ Jachmann, H. (1988). "Estimating age in African elephants: a revision of Laws' molar evaluation technique". African Journal of Ecology. 22 (1): 51–56. Bibcode:1988AfJEc..26...51J. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2028.1988.tb01127.x.

- ^ Raubenheimer, E. J.; Van Heerden, W. F. P.; Van Niekerk, P. J.; De Vos, V. & Turner, M. J. (1995). "Morphology of the deciduous tusk (tush) of the African elephant (Loxodonta africana)" (PDF). Archives of Oral Biology. 40 (6): 571–576. doi:10.1016/0003-9969(95)00008-D. PMID 7677604. Archived (PDF) from the original on 23 May 2022. Retrieved 2 June 2019.

- ^ Shoshani, J. (1996). "Skeletal and other basic anatomical features of elephants". In Shoshani, J.; Tassy, P. (eds.). The Proboscidea: Evolution and Palaeoecology of Elephants and Their Relatives. New York: Oxford University Press. pp. 9–20.

- ^ Raubenheimer, E. J.; Bosman, M. C.; Vorster, R. & Noffke, C. E. (1998). "Histogenesis of the chequered pattern of ivory of the African elephant (Loxodonta africana)". Archives of Oral Biology. 43 (12): 969–977. doi:10.1016/S0003-9969(98)00077-6. PMID 9877328.

- ^ Yalden, D. W.; Largen, M. J. & Kock, D. (1986). "Catalogue of the Mammals of Ethiopia. 6. Perissodactyla, Proboscidea, Hyracoidea, Lagomorpha, Tubulidentata, Sirenia, and Cetacea". Monitore Zoologico Italiano. Supplemento 21 (1): 31–103. doi:10.1080/03749444.1986.10736707.

- ^ a b Douglas-Hamilton, I. (1972). On the ecology and behaviour of the African elephant: the elephants of Lake Manyara (PhD thesis). Oxford: University of Oxford.

- ^ Douglas-Hamilton, I. (1973). "On the ecology and behaviour of the Lake Manyara elephants". East African Wildlife Journal. 11 (3–4): 401–403. Bibcode:1973AfJEc..11..401D. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2028.1973.tb00101.x.

- ^ Leuthold, W. (1976). "Group size in elephants of Tsavo National Park and possible factors influencing it". Journal of Animal Ecology. 45 (2): 425–439. Bibcode:1976JAnEc..45..425L. doi:10.2307/3883. JSTOR 3883.

- ^ Eltringham, S. K. (1977). "The numbers and distribution of elephant Loxodonta africana in the Rwenzori National Park and Chambura Game Reserve, Uganda". African Journal of Ecology. 15 (1): 19–39. Bibcode:1977AfJEc..15...19E. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2028.1977.tb00375.x.

- ^ Moss, C. J.; Poole, J. H. (1983). "Relationships and social structure of African elephants". In Hinde, R. A.; Berman, C. M. (eds.). Primate Social Relationships: An Integrated Approach. Oxford: Blackwell. pp. 315–325.

- ^ Allen, C. R. B.; Brent, L. J. N.; Motsentwa, T.; Weiss, M. N.; Croft, D. P. (2020). "Importance of old bulls: leaders and followers in collective movements of all-male groups in African savannah elephants (Loxodonta africana)". Scientific Reports. 10 (1): 13996. Bibcode:2020NatSR..1013996A. doi:10.1038/s41598-020-70682-y. PMC 7471917. PMID 32883968.

- ^ Martins, A. F.; Bennett, N. C.; Clavel, S.; Groenewald, H.; Hensman, S.; Hoby, S.; Joris, A.; Manger, P. R.; Milinkovitch, M. C. (2018). "Locally-curved geometry generates bending cracks in the African elephant skin". Nature Communications. 9 (1): 3865. Bibcode:2018NatCo...9.3865M. doi:10.1038/s41467-018-06257-3. PMC 6168576. PMID 30279508.

- ^ Mole, M. A.; Rodrigues DÁraujo, S.; van Aarde, R. J.; Mitchell, D.; Fuller, A. (2018). "Savanna elephants maintain homeothermy under African heat". Journal of Comparative Physiology B. 188 (5): 889–897. doi:10.1007/s00360-018-1170-5. PMID 30008137. S2CID 253886484.

- ^ Codron, Jacqueline; Codron, Daryl; Lee-Thorp, Julia A.; Sponheimer, Matt; Kirkman, Kevin; Duffy, Kevin J.; Sealy, Judith (January 2011). "Landscape-scale feeding patterns of African elephant inferred from carbon isotope analysis of feces". Oecologia. 165 (1): 89–99. Bibcode:2011Oecol.165...89C. doi:10.1007/s00442-010-1835-6. ISSN 0029-8549. PMID 21072541.

- ^ Valeix, Marion; Fritz, Hervé; Sabatier, Rodolphe; Murindagomo, Felix; Cumming, David; Duncan, Patrick (February 2011). "Elephant-induced structural changes in the vegetation and habitat selection by large herbivores in an African savanna". Biological Conservation. 144 (2): 902–912. Bibcode:2011BCons.144..902V. doi:10.1016/j.biocon.2010.10.029.

- ^ Campos-Arceiz, Ahimsa; Blake, Steve (November 2011). "Megagardeners of the forest – the role of elephants in seed dispersal". Acta Oecologica. 37 (6): 542–553. Bibcode:2011AcO....37..542C. doi:10.1016/j.actao.2011.01.014.

- ^ Estes, R. D. (1999). "Elephant Loxodonta africana Family Elephantidae, Order Proboscidea". The Safari Companion: A Guide to Watching African Mammals Including Hoofed Mammals, Carnivores, and Primates (Revised and expanded ed.). Vermont: Chelsea Green Publishing Company. pp. 223–233. ISBN 1-890132-44-6.

- ^ Ruggiero, R. G.; Fay, J. M. (1994). "Utilization of termitarium soils by elephants and its ecological implications". African Journal of Ecology. 32 (3): 222–232. Bibcode:1994AfJEc..32..222R. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2028.1994.tb00573.x.

- ^ Weir, J. S. (1969). "Chemical properties and occurrence on Kalahari sand of salt licks created by elephants". Journal of Zoology. 158 (3): 293–310. doi:10.1111/j.1469-7998.1969.tb02148.x.

- ^ Weir, J. S. (1972). "Spatial distribution of Elephants in an African National Park in relation to environmental sodium". Oikos. 23 (1): 1–13. Bibcode:1972Oikos..23....1W. doi:10.2307/3543921. JSTOR 3543921.

- ^ a b c Estes, R. (1991). The behavior guide to African mammals: including hoofed mammals, carnivores, primates. University of California Press. pp. 263–66. ISBN 978-0-520-08085-0.

- ^ Sukumar, R. (11 September 2003). The Living Elephants: Evolutionary Ecology, Behaviour, and Conservation. Oxford University Press, USA. p. 145. ISBN 978-0-19-510778-4. OCLC 935260783.

- ^ Poole, J. H.; Moss, C. J. (1981). "Musth in the African elephant, Loxodonta africana". Nature. 292 (5826): 830–1. Bibcode:1981Natur.292..830P. doi:10.1038/292830a0. PMID 7266649. S2CID 4337060.

- ^ Poole, J. H. (1982). Musth and male-male competition in the African elephant (PhD thesis). Cambridge: University of Cambridge.

- ^ Poole, J. H.; Kasman, L. H.; Ramsay, E. C.; Lasley, B. L. (1984). "Musth and urinary testosterone concentrations in the African elephant (Loxodonta africana)". Reproduction. 70 (1): 255–260. doi:10.1530/jrf.0.0700255. PMID 6694143.

- ^ Poole, J. H. (1987). "Rutting behavior in African elephants: the phenomenon of musth". Behaviour. 102 (3–4): 283–316. doi:10.1163/156853986X00171.

- ^ Poole, J. H. (1989). "Announcing intent: the aggressive state of musth in African elephants" (PDF). Animal Behaviour. 37 (37): 140–152. doi:10.1016/0003-3472(89)90014-6. S2CID 53190740. Archived from the original (PDF) on 1 June 2019. Retrieved 1 June 2019.

- ^ Slotow, R.; van Dyk, G.; Poole, J.; Page, B.; Klocke, A. (2000). "Older bull elephants control young males". Nature. 408 (6811): 425–426. Bibcode:2000Natur.408..425S. doi:10.1038/35044191. PMID 11100713. S2CID 136330.

- ^ Slotow, R.; van Dyk, G. (2001). "Role of delinquent young 'orphan' male elephants in high mortality of white rhinoceros in Pilanesberg National Park, South Africa". Koedoe (44): 85–94. Archived from the original on 7 May 2020. Retrieved 31 May 2019.

- ^ Slotow, R.; Balfour, D.; Howison, O. (2001). "Killing of black and white rhinoceroses by African elephants in Hluhluwe-Umfolozi Park, South Africa" (PDF). Pachyderm (31): 14–20. Archived from the original (PDF) on 25 October 2007.

- ^ Hanks, J. (1973). "Reproduction in the male African elephant in the Luangwa Valley, Zambia". South African Journal of Wildlife Research. 3 (2): 31–39.

- ^ Bokhout, B., & Nabuurs, M. (2005). Vasectomy of older bulls to manage elephant overpopulation in Africa: a proposal. Pachyderm, 39, 97-103.

- ^ a b c Williamson, B. R. (1976). "Reproduction in female African elephant in the Wankie National Park, Rhodesia". South African Journal of Wildlife Research. 6 (2): 89–93.

- ^ a b c Moss, C. J. (1983). "Oestrous behaviour and female choice in the African elephant". Behaviour. 86 (3/4): 167–196. doi:10.1163/156853983X00354. JSTOR 4534283.

- ^ Allen, W. (2006). "Ovulation, Pregnancy, Placentation and Husbandry in the African Elephant (Loxodonta africana)". Philosophical Transactions: Biological Sciences. 361 (1469): 821–834. doi:10.1098/rstb.2006.1831. PMC 1609400. PMID 16627297.

- ^ Poole, J. H.; Moss, C. J. (1989). "Elephant mate searching: group dynamics and vocal and olfactory communication". In Jewell, P. A.; Maloiy, G. M. O. (eds.). The Biology of Large African Mammals in Their Environment. Symposia of the Zoological Society of London. Vol. 61. London: Clarendon Press. pp. 111–125.

- ^ Kerr, M. A. (1978). "Reproduction of elephant in the Mana Pools National Park, Rhodesia". Arnoldia (Rhodesia). 8 (29): 1–11.

- ^ McKnight, B. L. (1992). "Birth of an African elephant in Tsavo East National Park, Kenya". African Journal of Ecology. 30 (1): 87–89. Bibcode:1992AfJEc..30...87M. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2028.1992.tb00481.x.

- ^ Lang, E. M. (1967). "The birth of an African elephant Loxodonta africana at Basle Zoo". International Zoo Yearbook. 7 (1): 154–157. doi:10.1111/j.1748-1090.1967.tb00359.x.

- ^ Smith, N. S.; Buss, I. O. (1973). "Reproductive ecology of the female African elephant". The Journal of Wildlife Management. 37 (4): 524–534. doi:10.2307/3800318. JSTOR 3800318.

- ^ Lee, P. C.; Moss, C. J. (1986). "Early maternal investment in male and female African elephant calves". Behavioral Ecology and Sociobiology. 18 (5): 353–361. Bibcode:1986BEcoS..18..353L. doi:10.1007/BF00299666. S2CID 10901693.

- ^ Lee, P. C.; Sayialel, S.; Lindsay, W. K.; Moss, C. J. (2012). "African elephant age determination from teeth: validation from known individuals". African Journal of Ecology. 50 (1): 9–20. Bibcode:2012AfJEc..50....9L. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2028.2011.01286.x.

- ^ Pacifici, M.; Santini, L.; Di Marco, M.; Baisero, D.; Francucci, L.; Grottolo Marasini, G.; Visconti, P.; Rondinini, C. (2013). "Generation length for mammals". Nature Conservation. 5 (5): 87–94. doi:10.3897/natureconservation.5.5734.

- ^ Sinclair, A. R. E.; Mduma, S. & Brashares, J. S. (2003). "Patterns of predation in a diverse predator-prey system". Nature. 425 (6955): 288–290. Bibcode:2003Natur.425..288S. doi:10.1038/nature01934. PMID 13679915. S2CID 29501319.

- ^ McComb, K.; Shannon, G.; Durant, S. M.; Sayialel, K.; Slotow, R.; Poole, J. & Moss, C. (2011). "Leadership in elephants: the adaptive value of age". Proceedings of the Royal Society of London B: Biological Sciences. 278 (1722): 3270–3276. doi:10.1098/rspb.2011.0168. PMC 3169024. PMID 21411454.

- ^ Loveridge, Andrew J.; et al. (2006). "Influence of drought on predation of elephant (Loxodonta africana) calves by lions (Panthera leo) in an African wooded savannah". Journal of Zoology. 270 (3): 523–530. doi:10.1111/j.1469-7998.2006.00181.x.

- ^ Joubert, D. (2006). "Hunting behaviour of lions (Panthera leo) on elephants (Loxodonta africana) in the Chobe National Park, Botswana". African Journal of Ecology. 44 (2): 279–281. Bibcode:2006AfJEc..44..279J. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2028.2006.00626.x.

- ^ Power, R. J.; Compion, R. X. S. (2009). "Lion predation on elephants in the Savuti, Chobe National Park, Botswana". African Zoology. 44 (1): 36–44. doi:10.3377/004.044.0104. S2CID 86371484. Archived from the original on 31 August 2018. Retrieved 19 April 2018.

- ^ Lemieux, A. M.; Clarke, R. V. (2009). "The international ban on ivory sales and its effects on elephant poaching in Africa". The British Journal of Criminology. 49 (4): 451–471. doi:10.1093/bjc/azp030.

- ^ a b Ceballos, G.; Ehrlich, A. H. & Ehrlich, P. R. (2015). The Annihilation of Nature: Human Extinction of Birds and Mammals. Baltimore, Maryland: Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 978-1421417189.

- ^ a b c Thouless, C. R.; Dublin, H. T.; Blanc, J. J.; Skinner, D. P.; Daniel, T. E.; Taylor, R. D.; Maisels, F.; Frederick, H. L.; Bouché, P. (2016). African Elephant Status Report 2016 : an update from the African Elephant Database. Occasional Paper of the IUCN Species Survival Commission No. 60. Gland: IUCN SSC African Elephant Specialist Group. ISBN 978-2-8317-1813-2.

- ^ Wasser, S. K.; Mailand, C.; Booth, R.; Mutayoba, B.; Kisamo, E.; Clark, B.; Stephens, M. (2007). "Using DNA to track the origin of the largest ivory seizure since the 1989 trade ban". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 104 (10): 4228–4233. Bibcode:2007PNAS..104.4228W. doi:10.1073/pnas.0609714104. PMC 1805457. PMID 17360505.

- ^ Poilecot, P. (2010). "Le braconnage et la population d'éléphants au Parc National de Zakouma (Tchad)". Bois et Forêts des Tropiques. 303 (303): 93–102. doi:10.19182/bft2010.303.a20454.

- ^ Douglas-Hamilton, I. (2009). "The current elephant poaching trend" (PDF). Pachyderm (45): 154–157. Archived (PDF) from the original on 11 July 2019. Retrieved 3 June 2019.

- ^ Wittemyer, G.; Daballen, D.; Douglas-Hamilton, I. (2013). "Comparative Demography of an At-Risk African Elephant Population". PLOS ONE. 8 (1): e53726. Bibcode:2013PLoSO...853726W. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0053726. PMC 3547063. PMID 23341984.

- ^ Wittemyer, G.; Northrup, J. M.; Blanc, J.; Douglas-Hamilton, I.; Omondi, P.; Burnham, K. P. (2014). "Illegal killing for ivory drives global decline in African elephants". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 111 (36): 13117–13121. Bibcode:2014PNAS..11113117W. doi:10.1073/pnas.1403984111. PMC 4246956. PMID 25136107.

- ^ Wasser, S. K.; Brown, L.; Mailand, C.; Mondol, S.; Clark, W.; Laurie, C.; Weir, B. S. (2015). "Genetic assignment of large seizures of elephant ivory reveals Africa's major poaching hotspots". Science. 349 (6243): 84–87. Bibcode:2015Sci...349...84W. doi:10.1126/science.aaa2457. PMC 5535781. PMID 26089357.

- ^ "Over 500 Rare Vultures Die After Eating Poisoned Elephants in Botswana". Agence France-Press. NDTV. 2019. Archived from the original on 8 November 2020. Retrieved 28 June 2019.

- ^ Hurworth, E. (2019). "More than 500 endangered vultures die after eating poisoned elephant carcasses". CNN. Archived from the original on 3 August 2021. Retrieved 28 June 2019.

- ^ Solly, M. (2019). "Poachers' Poison Kills 530 Endangered Vultures in Botswana". Smithsonian. Archived from the original on 2 May 2021. Retrieved 28 June 2019.

- ^ Ngounou, B. (2019). "Botswana: Over 500 vultures found dead after massive poisoning". Afrik21. Archived from the original on 26 January 2021. Retrieved 28 June 2019.

- ^ Jachmann, H.; Berry, P. S. M. & Imae, H. (1995). "Tusklessness in African elephants: a future trend". African Journal of Ecology. 33 (3): 230–235. Bibcode:1995AfJEc..33..230J. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2028.1995.tb00800.x.

- ^ Campbell-Staton, S. C.; Arnold, B. J.; Gonçalves, D.; Granli, P.; Poole, J.; Long, R. A. & Pringle, R. M. (2021). "Ivory poaching and the rapid evolution of tusklessness in African elephants". Science. 374 (6566): 483–487. Bibcode:2021Sci...374..483C. doi:10.1126/science.abe7389. PMID 34672738. S2CID 239457948.

- ^ "Facts About African Elephants – The Maryland Zoo in Baltimore". The Maryland Zoo in Baltimore. Archived from the original on 4 May 2018. Retrieved 13 November 2017.

- ^ a b Ortega, Joaquín; Corpa, Juan M.; Orden, José A.; Blanco, Jorge; Carbonell, María D.; Gerique, Amalia C.; Latimer, Erin; Hayward, Gary S.; Roemmelt, Andreas; Kraemer, Thomas; Romey, Aurore; Kassimi, Labib B.; Casares, Miguel (15 July 2015). "Acute death associated with Citrobacter freundii infection in an African elephant (Loxodonta africana)". Journal of Veterinary Diagnostic Investigation. 27 (5): 632–636. doi:10.1177/1040638715596034. PMID 26179092.

- ^ Lindeque, P. M. & Turnbull, P. C. (1994). "Ecology and epidemiology of anthrax in the Etosha National Park, Namibia". The Onderstepoort Journal of Veterinary Research. 61 (1): 71–83. PMID 7898901.

- ^ "Botswana: Lab tests to solve mystery of hundreds of dead elephants". BBC. 2020. Archived from the original on 3 July 2020. Retrieved 3 July 2020.

- ^ Miller, M.A.; Buss, P.; Roos, E.O.; Hausler, G.; Dippenaar, A.; Mitchell, E.; van Schalkwyk, L.; Robbe-Austerman, S.; Waters, W.R.; Sikar-Gang, A.; Lyashchenko, K.P.; Parsons, S.D.C.; Warren, R. & van Helden, P. (2019). "Fatal Tuberculosis in a Free-Ranging African Elephant and One Health Implications of Human Pathogens in Wildlife". Frontiers in Veterinary Science. 6: 18. doi:10.3389/fvets.2019.00018. PMC 6373532. PMID 30788347.

- ^ "Mysterious mass elephant die-off in Botswana was caused by cyanobacteria poisoning". sciencealert.com. AFP. 22 September 2020. Archived from the original on 23 September 2020. Retrieved 24 September 2020.

- ^ Brown, W. (2020). "Nerve agent fear as hundreds of elephants perish mysteriously in Botswana". The Telegraph. Archived from the original on 2 July 2020. Retrieved 3 July 2020.

- ^ King, L. E.; Douglas-Hamilton, I.; Vollrath, F. (2007). "African elephants run from the sound of disturbed bees". Current Biology. 17 (19): R832–R833. Bibcode:2007CBio...17.R832K. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2007.07.038. PMID 17925207. S2CID 30014793.

- ^ Nuwer, Rachel (25 March 2021). "Both African elephant species are now endangered, one critically". National Geographic. Archived from the original on 25 March 2021. Retrieved 25 March 2021.

- ^ Schulte, B. A. (2000). "Social structure and helping behavior in captive elephants". Zoo Biology. 19 (5): 447–459. doi:10.1002/1098-2361(2000)19:5<447::aid-zoo12>3.0.co;2-#.

Further reading

edit- Caitlin O'Connell (2015). Elephant Don: The Politics of a Pachyderm Posse. University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0226106113.

External links

edit- Elephant Information Repository Archived 18 March 2009 at the Wayback Machine – An in-depth resource on elephants

- "African Bush Elephant Loxodonta africana (Blumenbach 1797)". The Encyclopedia of Life.

- ARKive – images and movies of the African Bush Elephant (Loxodonta africana)

- BBC Wildlife Finder – Clips from the BBC archive, news stories and sound files of the African Bush Elephant

- View the elephant genome on Ensembl

- People Not Poaching: The Communities and IWT Learning Platform

- Handwerk, B. (2006). "African Elephants Slaughtered in Herds Near Chad Wildlife Park". National Geographic. Archived from the original on 1 September 2006. Retrieved 1 September 2006.