Affliction is a 1997 American neo-noir crime drama directed and written by Paul Schrader. Based on the 1989 novel by Russell Banks, the film stars Nick Nolte, Sissy Spacek, James Coburn, and Willem Dafoe.

| Affliction | |

|---|---|

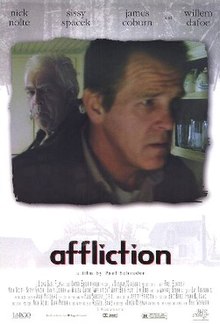

Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | Paul Schrader |

| Screenplay by | Paul Schrader |

| Based on | Affliction by Russell Banks |

| Produced by | Linda Reisman |

| Starring | |

| Cinematography | Paul Sarossy |

| Edited by | Jay Rabinowitz |

| Music by | Michael Brook |

Production companies |

|

| Distributed by |

|

Release dates |

|

Running time | 114 minutes |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $6 million |

| Box office | $6.3 million[2][3] |

Affliction had its world premiere at the 54th Venice International Film Festival on August 28, 1997, and was released in the United States on December 30, 1998, by Lions Gate Films. The film received positive reviews from critics, who mostly lauded the performances of Nolte and Coburn. At the 71st Academy Awards, Nolte was nominated for Best Actor and Coburn won for Best Supporting Actor. It earned six nominations at the 14th Independent Spirit Awards, including Best Feature.[4][5]

Plot

editRolfe Whitehouse begins the film, announcing the story of his brother Wade's "strange criminal behavior" and subsequent disappearance.

Wade Whitehouse is a small-town policeman in New Hampshire. On Halloween night, Wade meets his daughter Jill, but he is late and the evening is overshadowed by disharmony. Jill eventually calls her mother, Wade's ex-wife, to come and pick her up. When his ex-wife finally arrives, Wade shoves her husband against their car and watches them drive away with Jill. Wade vows to get a lawyer to help gain custody of his daughter.

The next day, Wade rushes to the scene of a crime. Jack Hewitt, a local hunting guide, claims that Evan Twombley, with whom he was hunting, accidentally shot and killed himself. The police believe Jack, but Wade grows suspicious, believing that the man's death was no accident. When he is informed that the victim was scheduled to testify in a lawsuit, his suspicion slowly turns into conviction.

A while later, Wade and his girlfriend Margie Fogg arrive at the house of Wade's alcoholic father, Glen Whitehouse, whose abusive treatment of Wade and Rolfe as children is seen in flashbacks throughout the film. Wade finds his mother lying dead in her bed from hypothermia. Glen reacts to her death with little surprise, and later gets drunk at her wake and gets into a fight with Wade.

Rolfe, who has come home for the funeral, suggests at first that Wade's murder theory could be correct, but later renounces himself of this presumption. Nonetheless, Wade becomes obsessed with his conviction. When Wade learns that town Selectman Gordon Lariviere is buying up property all over town with the help from a wealthy land developer, he makes the solving of these incidents his personal mission. Suffering from a painful toothache and becoming increasingly socially detached, he behaves more and more unpredictably. He follows Jack, convinced that Jack is running away from something and is involved in a conspiracy. After a car chase, a nervous Jack finally pulls over, threatens Wade with a rifle, shoots out his tires, and drives off.

Finally, Wade is fired for harassing Jack and trashing Lariviere's office. He collects Jill from her mother's house, where his ex-wife furiously castigates him over his plans to sue for full custody. At a local restaurant, he attacks the bartender in front of his daughter. Then Wade takes Jill home to find Margie leaving him. Wade grabs Margie and begs her to stay, but Jill rushes up and tries to stop the fight. In response, Wade angrily pushes Jill, giving her a bloody nose, forcing both her and Margie to drive off.

Wade is then approached by Glen, who congratulates him for finally acting as a "real man". The latent aggression between the men culminates in another fight in which Wade hits his father with the butt of a rifle, accidentally killing him. Wade burns the corpse in the barn, sits down at the kitchen table and starts drinking.

Rolfe's narration reveals that Wade eventually murdered Jack and left town (possibly to Canada, where Jack's truck was found three days later), never to return. Rolfe relates that the town later became part of a huge ski resort partly organized by Gordon Lariviere, but having nothing to do with either Jack or Twombley. Rolfe concludes that someday a vagrant resembling Wade might be found frozen to death, and that will be the end of the story.

Cast

edit- Nick Nolte as Wade Whitehouse

- James Coburn as Glen Whitehouse

- Sissy Spacek as Margie Fogg

- Willem Dafoe as Rolfe Whitehouse

- Mary Beth Hurt as Lillian Whitehouse

- Brigid Tierney as Jill Whitehouse

- Holmes Osborne as Gordon LaRiviere

- Jim True-Frost as Jack Hewitt

- Tim Post as Chick Ward

- Christopher Heyerdahl as Frankie Lacoy

- Marian Seldes as Alma Pittman

- Janine Theriault as Hettie Rogers

- Paul Stewart as Mr. Horner

- Wayne Robson as Nick Wickham

- Sean McCann as Evan Twombley

- Sheena Larkin as Lugene Brooks

- Penny Mancuso as Woman Driver

Production

editAccording to Paul Schrader, he came across a paperback copy of the novel in a bookstore and bought it after he was "grabbed" by its first sentence. After he finished reading the book, Schrader bought the film rights from Russell Banks.[6][7] The director said in an interview with Filmmaker that he identified with the characters in the story: "I had a very strong father and an older male sibling. My father was not abusive, he was not alcoholic, but there were enough similarities. I came from that part of the country with long cold winters, so I knew these people, and I knew their violence."[6] Although it has been compared to his previous films (e.g. Taxi Driver, American Gigolo and Light Sleeper), Schrader has stated that the ending of Affliction was what made it different from them: "One of the differences between things that I have written and Russell's book is that I tend to end my pieces on a kind of grace note, and this one has none. I like some sense of moral grace. But Affliction is pretty bleak at the end."[6] He also added, "I view the film as a collaboration between myself and Russell Banks."[6]

Nick Nolte was Schrader's first choice for the role of Wade Whitehouse. Schrader told Charlie Rose that he envisioned Nolte in his mind while he was writing the script.[8] According to Schrader, he offered Nolte the part five years before filming began, when the actor had become a bankable star following his success with the box office hits The Prince of Tides and Cape Fear, both released in 1991. Although Nolte was interested in playing Wade, Schrader could not afford him at first. It was not until five years later when Nolte agreed to do Affliction for less money.[6][7] However, Nolte says he initially turned it down because he was working on other projects at the time and that he was not ready to portray the role.[9][10] It was Nolte who brought Affliction to the attention of Bart Potter, the head of Largo Entertainment.[10] Nolte told Rose that by the time the five years passed by, "I think I understood Wade better." Schrader also admitted that the five years of preparation helped Nolte's performance.[8] In addition to acting in the film, Nolte also served as one of its executive producers.[9]

Nolte says that he was the one who convinced Sissy Spacek, whom he worked with in Heart Beat (1980), to appear in Affliction alongside him.[9] According to Schrader, it was Spacek's husband Jack Fisk who came up with the idea of having the characters of Wade and Glen Whitehouse lick salt off their hands to show how similar the father and son are to each other.[8]

Schrader told Roger Ebert that he gave the part of Glen to James Coburn because he was bigger than and could "convincingly dominate" Nolte. When Schrader encouraged the actor to prepare for the role, Coburn reportedly said in response, "Oh, you mean you want me to really act? I can do that. I haven't often been asked to, but I can."[11]

Schrader claimed that Willem Dafoe wanted to play the part of Wade.[6] Dafoe himself would admit, "I knew I couldn't play Wade Whitehouse whether Nick Nolte was around or not." Schrader instead offered Dafoe the role of Rolfe Whitehouse, and the latter accepted it because he loved the novel. According to Dafoe, Schrader showed him the novel during the making of Light Sleeper.[8]

Affliction was filmed in Quebec, with principal shooting starting in February 1997. Although first presented at the Venice Film Festival on August 28 the same year, Affliction did not see a theatrical release until some time later in most countries. After a limited release in New York in December 1998, it saw its regular US release in January 1999.[12][13]

Reception

editOn Rotten Tomatoes, Affliction has an approval rating of 88% based on 50 reviews from critics, with an average rating of 7.60/10. The consensus reads, "Dark and bleak, the 'kick-ass' performances, especially Nolte's 'effective' portrayal of an abused soul, is the reason to see this film."[14] On Metacritic, the film has a score of 79 out of 100 based on 39 reviews, indicating "generally favorable reviews".[15]

Critic Roger Ebert of the Chicago Sun-Times gave the film 4 stars.[11] Janet Maslin in The New York Times wrote "[Nick Nolte] gives the performance of his career in Paul Schrader's quietly stunning new film [...] Like The Sweet Hereafter, a more meditative and elegant but less immediate, volcanic film, Affliction finds the deeper meaning in an all too believable tragedy."[16]

In a negative review in the Time Out Film Guide, Geoff Andrew called the film a "sensitive but rather dull adaption of Russell Banks' novel [...] the narrative's too unfocused and low-key really to engage the heart or mind."[17]

Awards and nominations

editSee also

editReferences

edit- ^ Roman, Monica (February 7, 1999). "JVC to forgo Largo". Variety. Retrieved October 29, 2021.

- ^ "Affliction (1997)". Box Office Mojo. Retrieved August 13, 2021.

- ^ "Affliction (1998)". The Numbers. Retrieved August 13, 2021.

- ^ Klady, Leonard (January 7, 1999). "'Affliction' leads way in indie Spirit noms". Variety. Retrieved August 13, 2021.

- ^ Munoz, Lorenza (January 8, 1999). "'Affliction' Tops Spirit Nods; 'High Art' Is Second in Tally". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved August 13, 2021.

- ^ a b c d e f Zeman, Josh (Winter 1998). "Sins of the Father". Filmmaker. Retrieved May 15, 2017.

- ^ a b Emery, Robert J. (2003). The Directors: Take Three. Skyhorse Publishing, Inc. ISBN 9781621531159.[page needed]

- ^ a b c d Rose, Charlie; Schrader, Paul; Nolte, Nick; Coburn, James; Dafoe, Willem (January 5, 1999). "'Affliction'". Charlie Rose (TV series). PBS.

- ^ a b c Harris, Will (October 27, 2016). "Nick Nolte on dropping acid and putting porno mags in Andy Griffith's cop car". The A.V. Club. Retrieved May 15, 2017.

- ^ a b Simon, Alex (December 1998). "Nick Nolte: Rebel, Rebel". The Hollywood Interview. Venice Magazine. Retrieved May 15, 2017.

- ^ a b Ebert, Roger (February 8, 1999). "Affliction". Chicago Sun-Times. Retrieved December 6, 2020.

- ^ Affliction production slate in American Cinematographer magazine, November 1998, retrieved January 2, 2012.

- ^ Affliction in the Internet Movie Database.

- ^ "Affliction (1997)". Rotten Tomatoes. Fandango. January 15, 1999. Retrieved January 29, 2021.

- ^ "Affliction Reviews". Metacritic. CBS Interactive. Retrieved January 29, 2021.

- ^ Maslin, Janet (December 30, 1998). "Affliction (1997) FILM REVIEW; A Suppressed Son Erupts With Molten Emotions". The New York Times. Retrieved October 29, 2011.

- ^ Andrew, Geoff (2002). Pym, John (ed.). Time Out Film Guide (11th ed.). New York City: Penguin Books. ISBN 978-0140294149.

- ^ "The 71st Academy Awards (1999) Nominees and Winners". Oscars.org. Retrieved November 19, 2011.

- ^ "Affliction – Golden Globes". HFPA. Retrieved July 5, 2021.

- ^ "36 Years of Nominees and Winners" (PDF). Independent Spirit Awards. Retrieved August 13, 2021.

- ^ "The 24th Annual Los Angeles Film Critics Association Awards". Los Angeles Film Critics Association. Retrieved July 5, 2021.

- ^ "Past Awards". National Society of Film Critics. December 19, 2009. Retrieved July 5, 2021.

- ^ "New York Film Critics Circle Awards: 1998 Awards". New York Film Critics Circle. 1999. Retrieved September 16, 2016.

- ^ "3rd Annual Film Awards (1998)". Online Film & Television Association. Retrieved May 15, 2021.

- ^ "International Press Academy website – 1999 3rd Annual SATELLITE Awards". Archived from the original on February 1, 2008.

- ^ "The 5th Annual Screen Actors Guild Awards: Nominees and Recipients". Screen Actors Guild. 1999. Retrieved September 16, 2016.

- ^ "The 20th Annual Youth in Film Awards". Young Artist Awards. Archived from the original on November 28, 2016. Retrieved March 24, 2017.